Assessment of Community Behavior and COVID-19 Transmission during Festivities in India: A Qualitative Synthesis through a Media Scanning Technique

Abstract

:1. Introduction

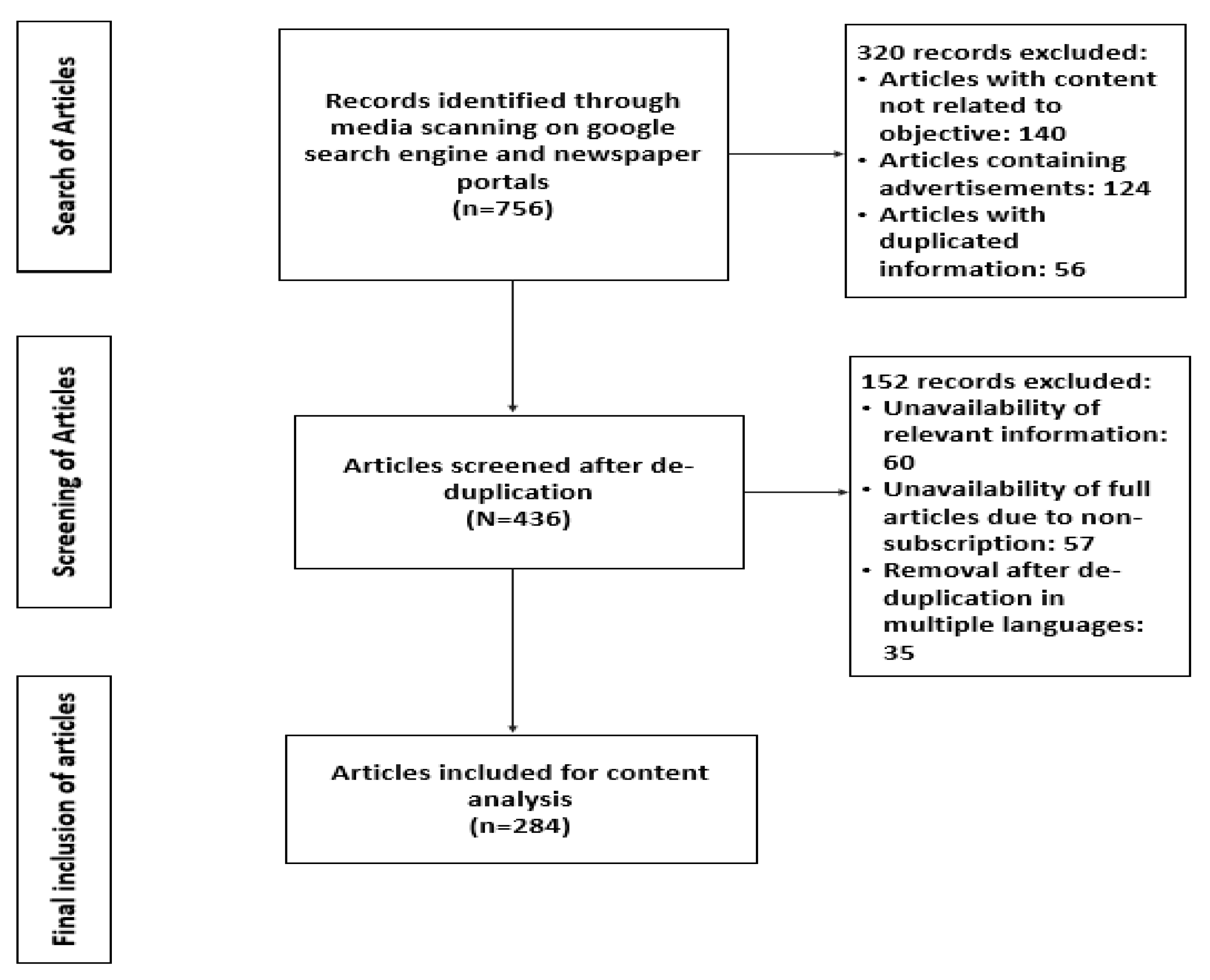

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.1.1. Screening of Festivals and the Media Scanning Methodology

2.1.2. News Article Search Strategy

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Media Scanning

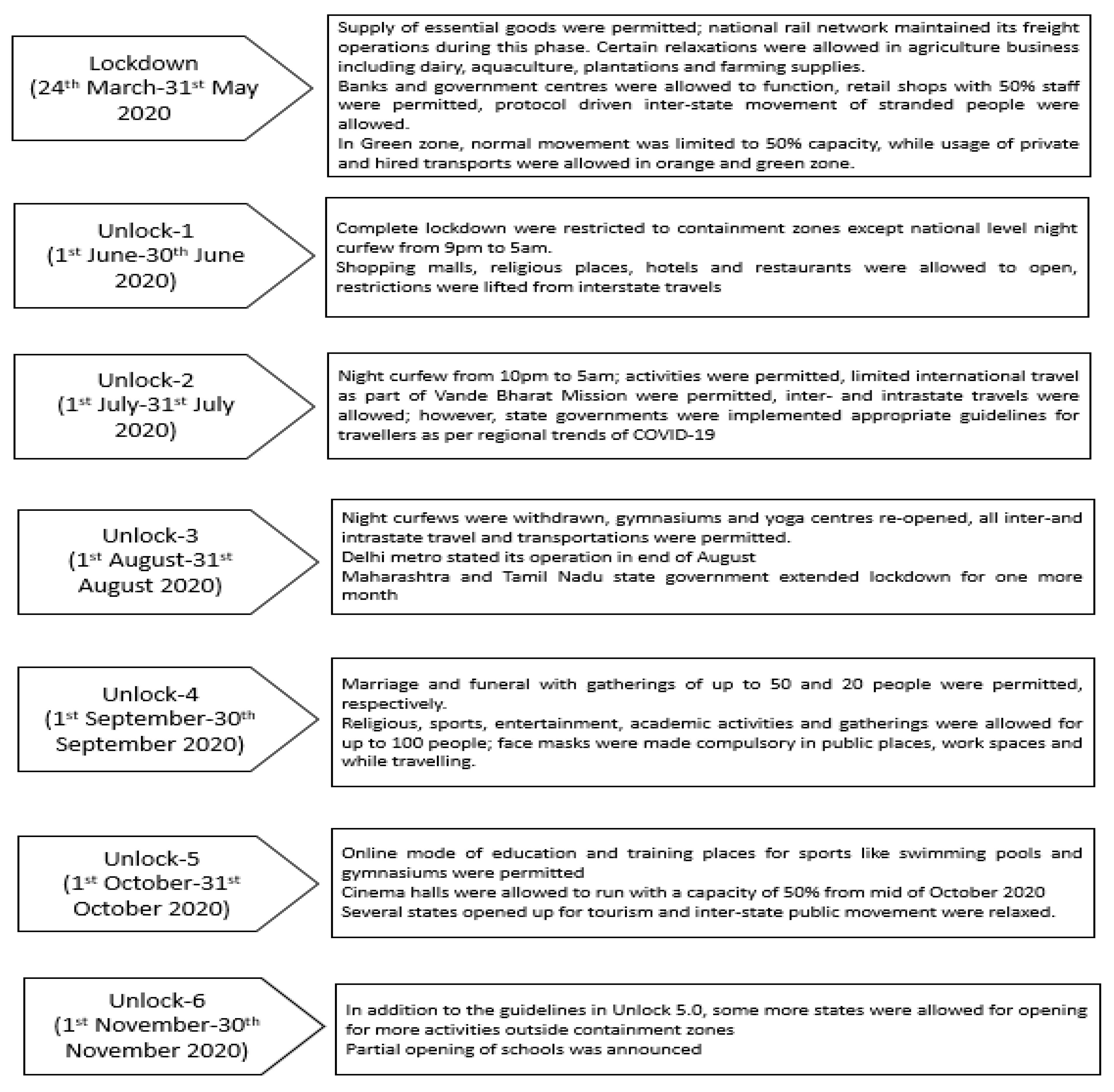

2.1.3. Guidelines Related to Lockdown

2.2. Data Analysis

2.2.1. Identification of Behavior Domains and Cross-Verification

2.2.2. Content Analysis

2.2.3. Estimating the Adjusted Test Positivity Ratio

3. Results

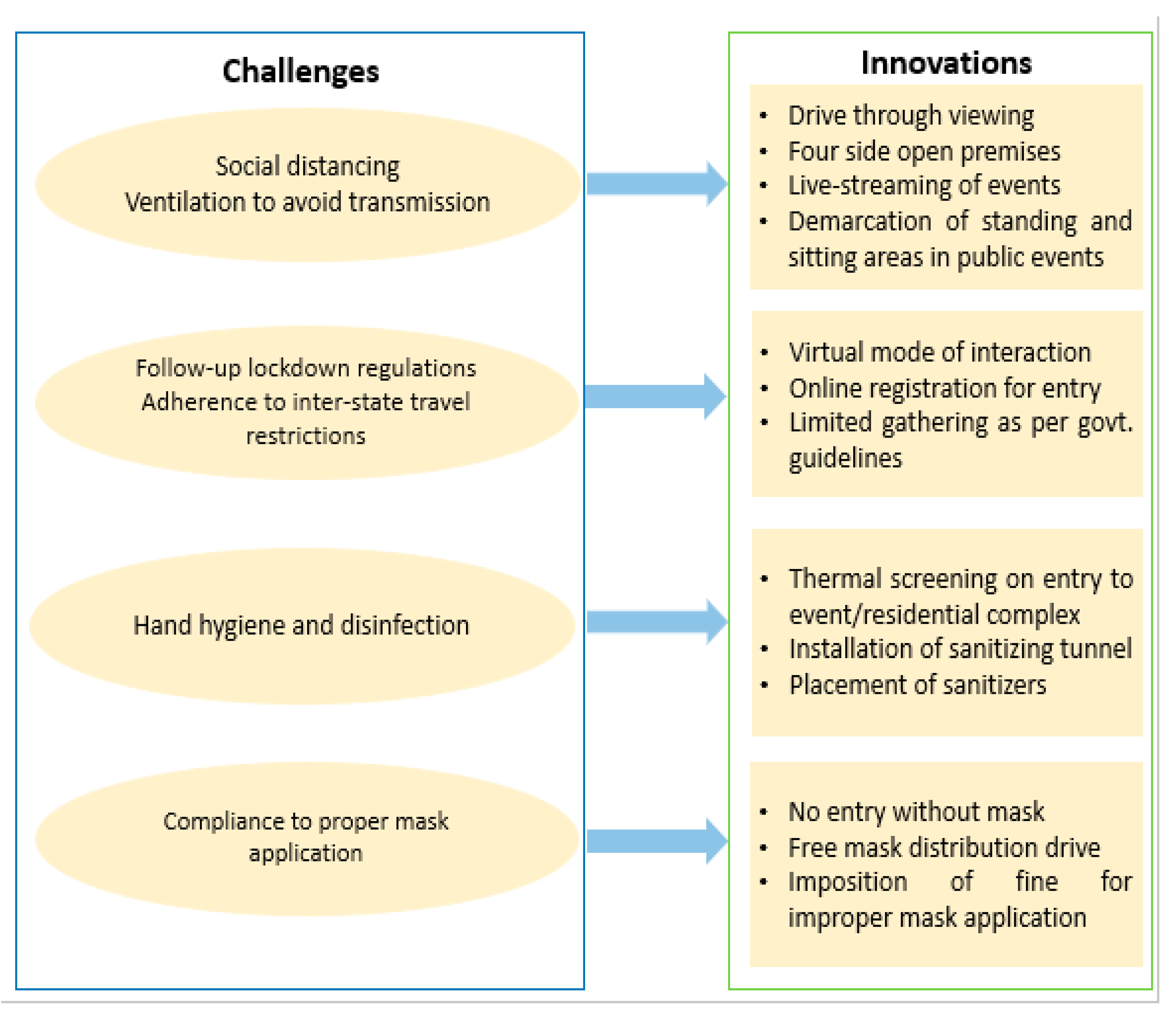

3.1. Identification of Challenges and Innovations

- Micro parameters to assess individual-centric COVID prevention behavior. Content analysis showed that three individual-level CABs were reported during various festive and peri-festive events to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Various guidelines from the Government of India also highlighted three individual-centric CABs to lower the risk of disease transmission, as follows:

- (a)

- Compliance with proper mask application. The first domain was identified as adherence to the mask mandate, which included the mindful use of face masks by individuals in public spaces. Shopping malls and event venues had implemented ‘no mask, no entry’ policies, while mask distribution drives were organized on various occasions. The use of face masks by individuals in public areas was observed to be followed appropriately across Indian cities, as reported by 61% of media articles.

- (b)

- Hand hygiene. News reports captured usage of hand sanitizers, the maintenance of hand hygiene on an individual level, and the installation of sanitizing measures at public events. A lack of compliance with proper hand hygiene among individuals across India was reported in 59% of the news articles analyzed in this study.

- (c)

- Practicing social distancing measures. As per the news reports, individuals cautiously avoided overcrowded public spaces. In order to handle overcrowding and problems related to ventilation in event venues, certain innovations were also put in place, such as drive-through and/or four-side-open pandals (temporary sheds for worshipping idols), and the demarcation of spaces to maintain safe distances between individuals. Through content analysis of visual materials, it was reported in 60% of news reports that individuals followed social distancing during pre-festive and festive events in most situations. However, some events witnessed the flouting of guidelines related to social gatherings, as reported in 40% of the reports.

- Macro parameters to assess community-centric COVID prevention behavior. Residential welfare associations (RWAs) and local authorities chose to develop innovative venues for festive events to prevent the spread of COVID-19. A total of five domains were identified to assess community-based (macro-level) CABs as reflected through media reports across various cities.

- (a)

- Mass/community disinfection measures. The first domain was taken as community-level adoption of disinfection measures. A lack of proper disinfection measures was reported in 72.5% of the media articles. However, certain innovative precautionary measures, such as installing sanitizer dispensing machines or sanitization tunnels at the venues of events, and time-to-time sanitization of idols, pandals and event premises, were also reported.

- (b)

- Temperature screening measures. Thermal screening of individuals in public places was one of the most common community adopted preventive measure adopted across the country. However, 78% articles reported the absence or improper implementation of this measure in festive celebration venues.

- (c)

- Appropriateness of premises. About a third of the news reports highlighted events being organized in open spaces to avoid crowding and poor ventilation. However, adherence to these guidelines to avoid overcrowding at celebration events varied geographically. Interestingly, a similar proportion of news reports indicated that most individuals were celebrating festivals within their residential premises and respective houses with families in a restricted fashion. Local community administrations conducted small-scale celebrations as per the government guidelines in all zones, mainly during Ganesh Utsav, followed by Durga Pooja (the festival for worship of Goddess Durga) and Dussehra (the festival involving the burning of effigies of Ravana, symbolizing Lord Rama’s victory over him), which were telecast on media platforms to keep people at home and experience the festive atmosphere from indoors. In one innovative approach adopted in Kolkata, drive-through viewings of idols and pandals were organized during Durga Pooja. Twenty seven percent of the media-scanned reports indicated that preventive guidelines were flouted.

- (d)

- Gathering as per guidelines. Through stringent guidelines, state governments restricted public gatherings in large numbers through different phases of unlocking to avoid a surge in COVID-19 cases. As a result, it was observed that all the regions reported a considerable number of cancellations of public events (34%).

- (e)

- Virtual modes of viewing holy idols in the pandals (darshan) and the live-streaming of festival-related events were reported in 18% of the media reports. This kind of innovation has been described as a networked event, and was reported primarily from Mumbai and Ahmedabad during Ganesh Utsav and Krishna Janmashtami (the festival celebrating the birth of Lord Krishna). About a fourth of the reports highlighted breaches of restricted gathering guidelines from several cities.

- (f)

- Crowd management. Print media and visual aids reported on crowd management by police, communities, and local community-based organizational associations. However, non-cooperative behavior and flouting of the guidelines by individuals were also reported. Laxity around retail shopping and recreational and religious travel was reported in 32% of the media reports.

- (g)

- Notably, a few examples of good crowd management during festivities were identified. Two such events were the Ram Janmabhoomi foundation-stone-laying ceremony in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, and Jagannath Puri Rath Yatra (the Chariot of Lord Jagannath) in Puri, Odisha, in August 2020. According to the reports, management and local authorities allowed limited attendance to those with COVID-19-negative test results. Furthermore, in October 2020, specific measures were endorsed for maximum attention and usage by individuals and communities, especially during the festive season as part of the Jan Andolan campaign. During Mysore Dussehra, approximately 200 people gathered at the Mysore Palace; however, the duration of the cultural programs and the number of artists were reduced considerably; these restrictions were accompanied by the observation of proper sanitization measures.

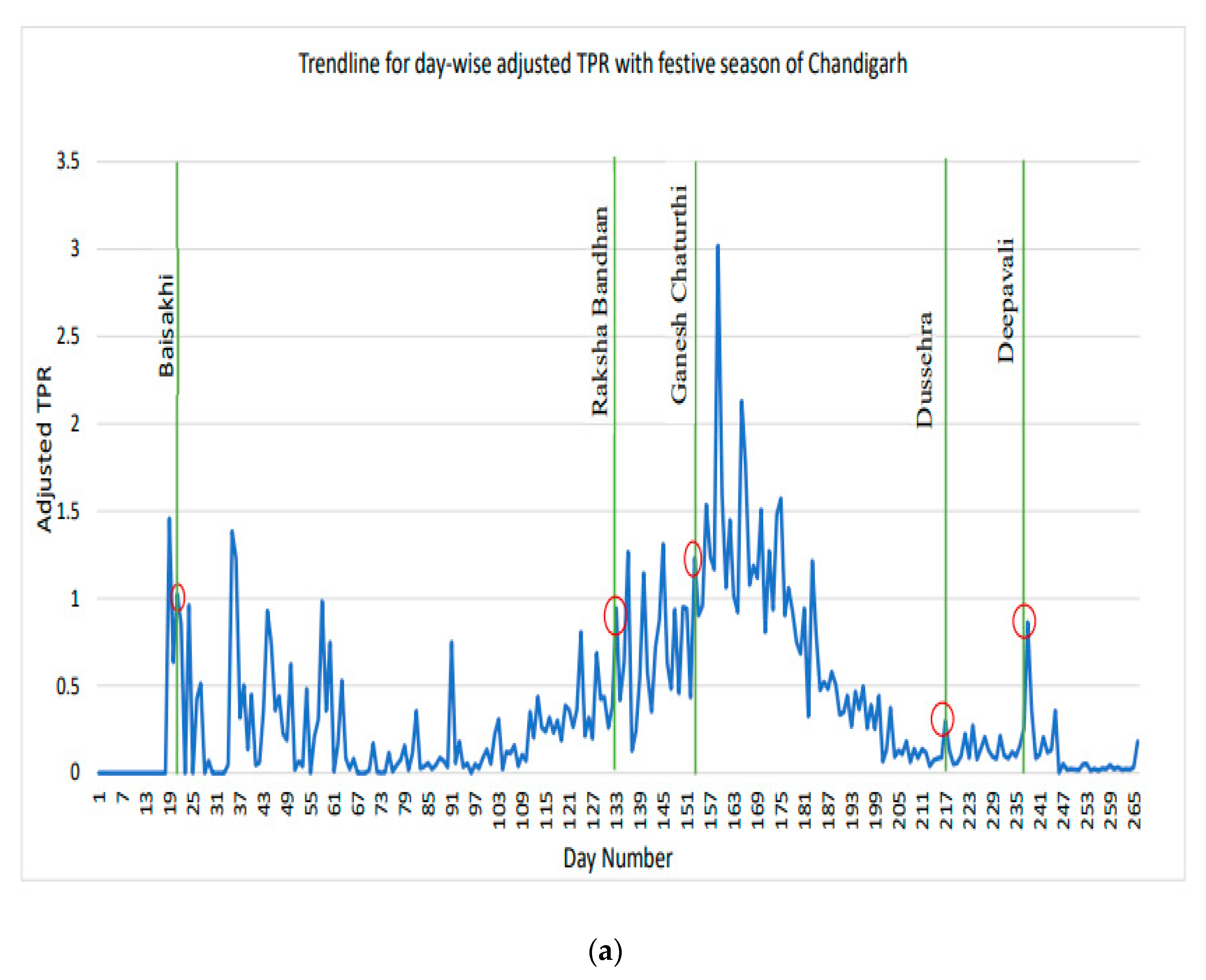

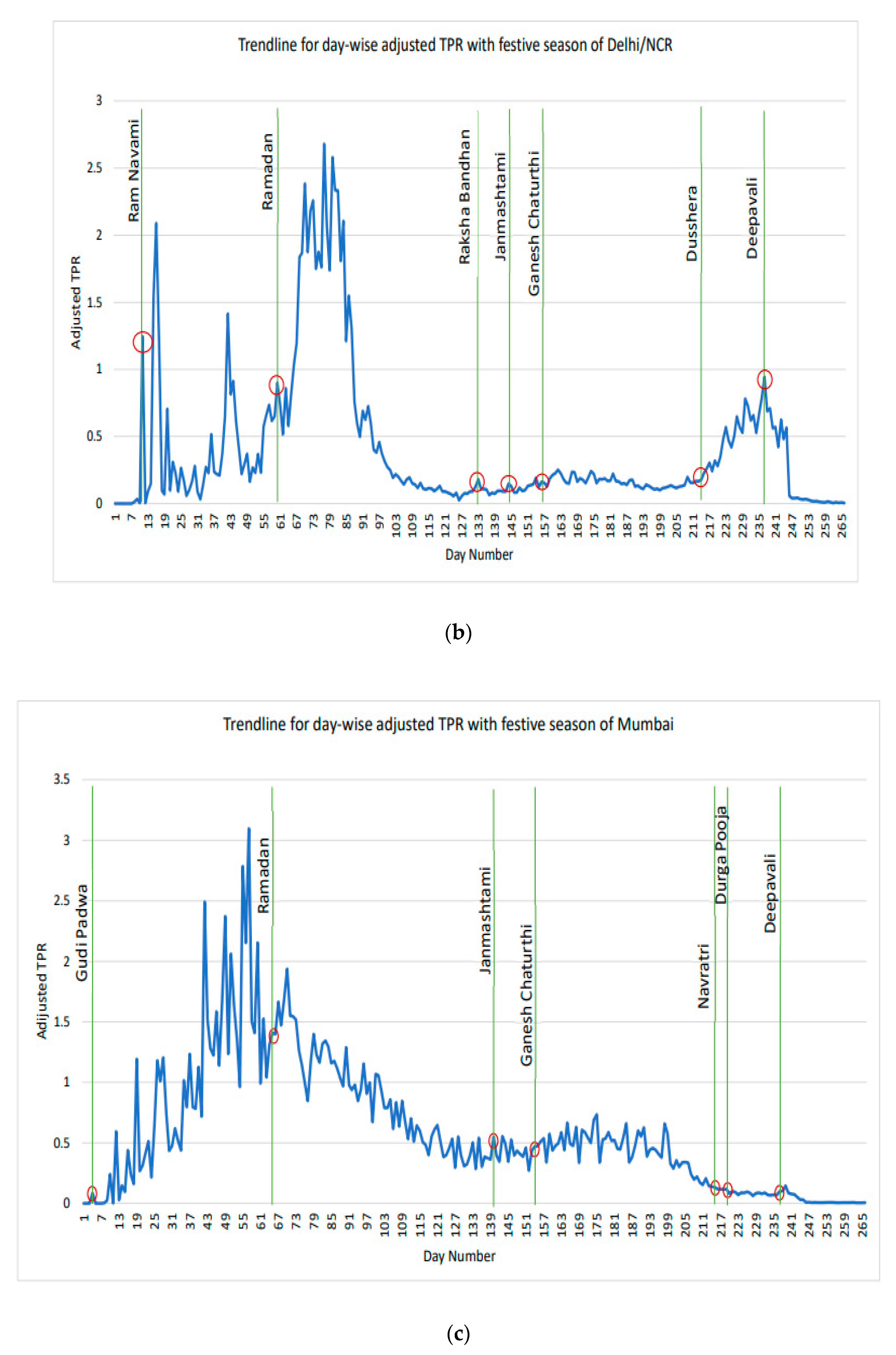

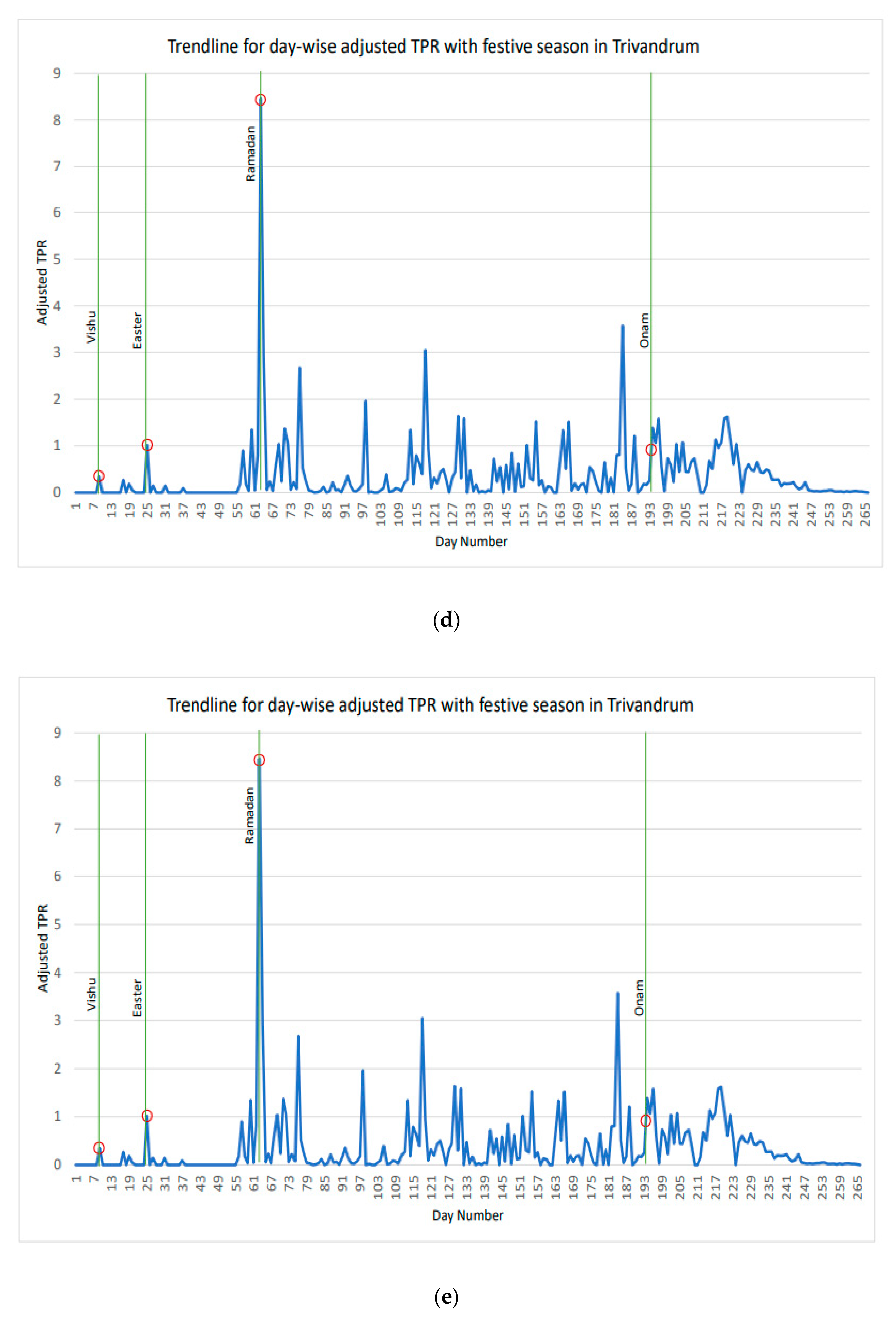

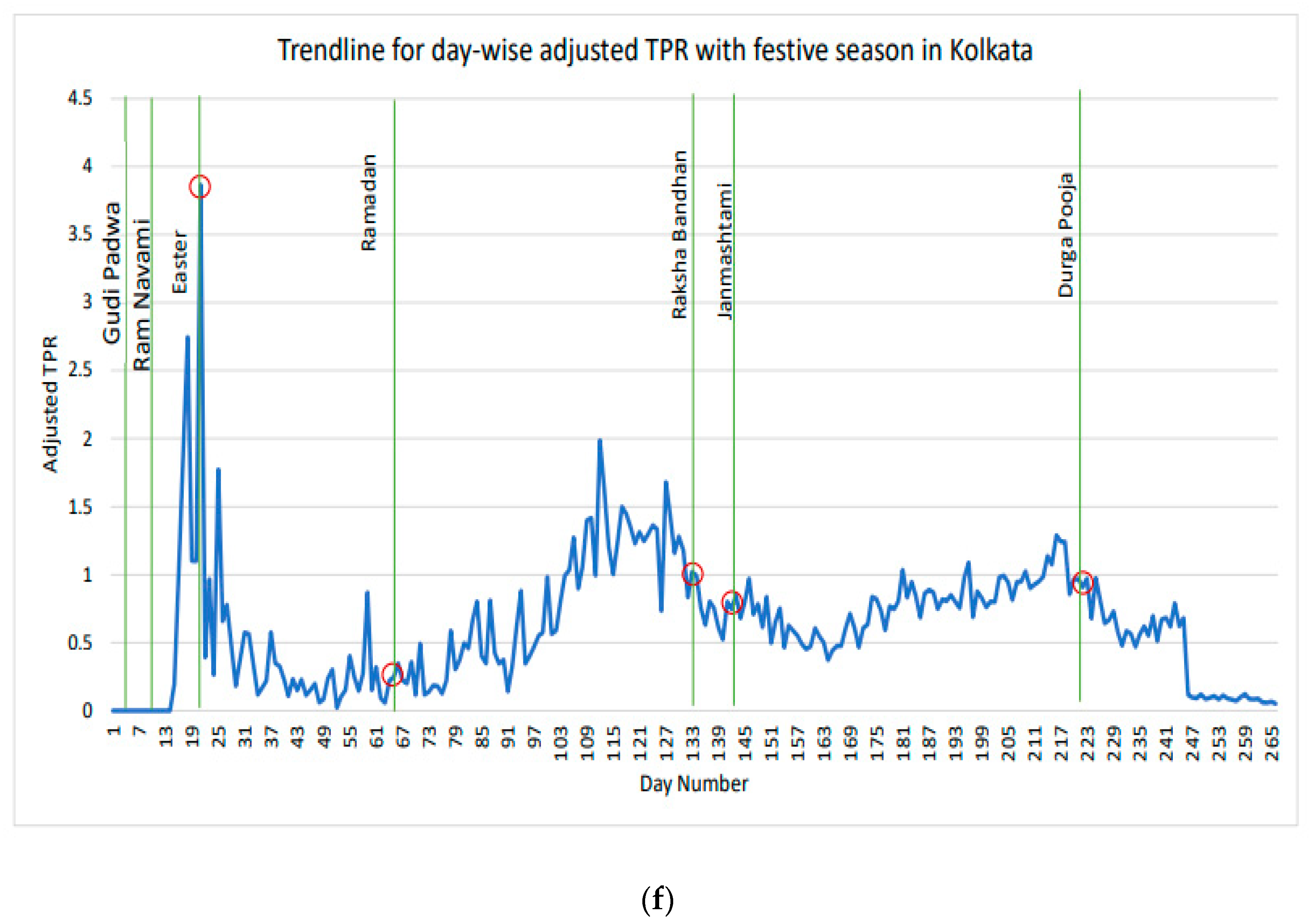

3.2. Trend of ATPR during Major Festivals and the Peri-Festival Season

4. Discussions

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

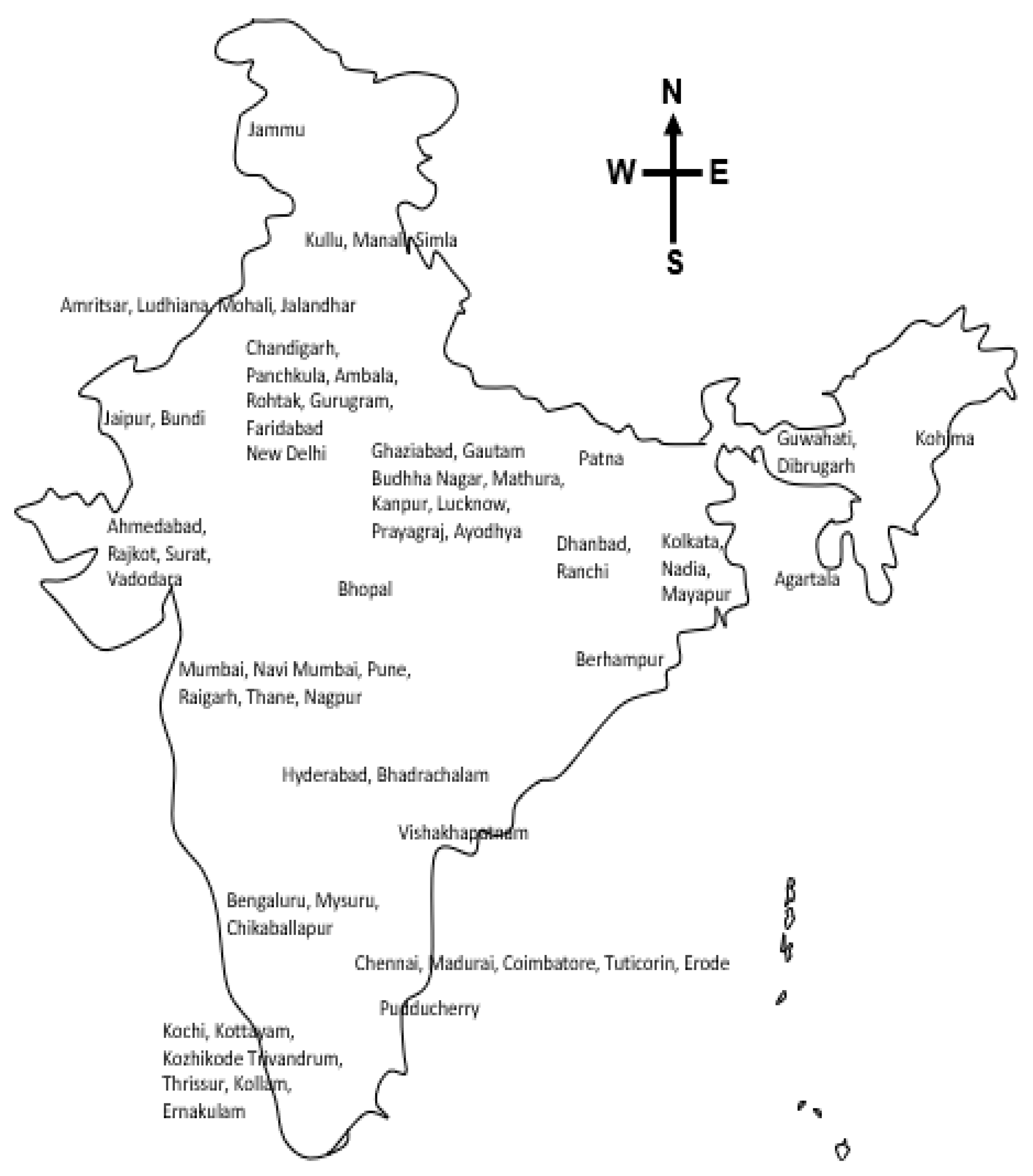

| COVID-19 Timeline | Festival and Timeline | Festive/Pre-Festive Activities | Geographical Locations Covered and Number of Articles Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lockdown | Gudi Padwa (March 2020) | This festival marks the new year for people in the Maharashtra and Konkan regions. It is celebrated by decorating floors with colorful rangolis, and hoisting a special Gudi flag on the house terrace. People are involved in shopping for new clothes, garlands, and fruits. The festivities include street processions, dancing, and community feasting. | Mumbai, Navi Mumbai, Lucknow, Kolkata, Bengaluru, Chikballapur, Mysuru (28) |

| Lockdown | Ugadi (March 2020) | It is a festival of social merriment. The preparations begin a week prior, when people buy clothes and new items for their houses, and decorate the entrances of their houses with fresh mango leaves. | |

| Lockdown | Rama Navami (April 2020) | This festival is celebrated to mark the birth of Lord Rama and falls on ninth day of Vasant Navratri. The celebrations involve Rath Yatra in Ayodhya and mass street processions. Devotees flock to temples seeking blessings from Lord Ram, Goddess Sita, and Hanuman in most parts of North, East and West India. In Karnataka, an annual Music Festival has been held on Ram Navami for the last 80 years. | Kolkata, Mysuru, Ayodhya, New Delhi, Bhadrachalam, Bundi (6) |

| Lockdown | Good Friday and Easter (April 2020) | Carnivals are organized along with processions. Sunday mass is conducted to mark the culmination of the three days of festivities and reverence to Lord Jesus Christ. | Lucknow, Kochi, Kottayam, Kolkata, Trivandrum, Kohima, Amritsar, Chandigarh, Jammu (24) |

| Lockdown | Baisakhi (April 2020) | It is a harvest festival which is accompanied by the organization of feasts and fairs to celebrate good crop yields. People go to local gurudwaras and seek prayers. Street processions are also organized by Gurudwaras for the celebration | |

| Lockdown | Vishu (April 2020) | This festival involves the tradition of buying new clothes and items for the decoration of houses. Elders give money and presents to young children and contribute to charity. Children enjoy firecrackers and sweets. Community feasts are also organized. | |

| Lockdown | Ramadan and Eid (May–June 2020) | Namaz and prayers are organized, and a full-day fast is observed by Muslim families. Two meals are served in each household, Sehri (morning time) and Iftaari (evening), where families gather and celebrate for a feasting tradition. Shopping for clothes and food items, and social gatherings for prayers and feasting are common sights. Women prepare celebratory dishes and apply henna, and all family members acquire new clothes for the festival. After the conclusion of the holy month of Ramadan, a festival of the breaking of the fast, known as Eid al-Fitr, is celebrated. | New Delhi, Kozhikode, Ahmedabad, Mumbai, Pune, Hyderabad, Kolkata (28) |

| Unlocking phases 1–2 | Bonalu (July 2020) | A festival for thanksgiving to Goddess Yellamma after the fulfilment of vows. Teenage girls dress up in half sarees, adult women visit temple, some women go into a trance where they dance to rhythmic beats to please the Goddess. Street processions are held, following which feasts are organized to serve the Goddess; these feasts are then shared with families and guests. | Hyderabad (6) |

| Unlocking phase 3 | Raksha Bandhan (August 2020) | Pre-festive shopping for clothes, rachis and gifts is a common occurrence. Movement on the day of Raksha Bandhan is observed as sisters visit their brothers’ homes to celebrate this festival | New Delhi, Rohtak, Ghaziabad, Gurugram, Chandigarh, Amritsar, Gautam Budhha Nagar, Ahmedabad, Raigarh, Berhampur, Kolkata (16) |

| Unlocking phase 3 | Janmashtami (August 2020) | This festival is celebrated with great enthusiasm in various parts of India. In Mumbai, the Hindu communities have a tradition of dahi handi, in which human pyramids are formed to break handis scaffolded at a height. Similarly, in Tamil Nadu, boys dressed as Krishna climb on oiled poles, on which are pots filled with money. In parts of Northern India, children dress up as Radha and Krishna, and devotees visit temple, pray, and sing devotional songs in groups, and celebrate the birth of Lord Krishna at midnight. | Ludhiana, Mathura, Rajkot, Mumbai, Thane, Vishakhapatnam, Kolkata, Nadia, Mayapur (18) |

| Unlocking phase 3 | Ganesh Utsav (August 2020) | Ganesh idols are installed in houses or in community pandals for three, five, or ten days. The festival culminates with the immersion of the Ganesh idol, and large processions are conducted in which people dance and sing while the immersion ritual takes place at a nearby body of water. | Mumbai, Pune, Nagpur, Surat, New Delhi, Gurugram, Hyderabad, Chennai, Pudducherry (26) |

| Unlocking phases 3–4 | Onam (September 2020) | Onam celebrations include boat races (Vallam Kali), tiger dances (Pulikali), flower rangoli making (Pookkalam), tugs of war, mask dances (kummattikali), and martial arts (Onathally), and music and folk-dancing programs are organized. Families visit their relatives with gifts, and feasts are a common sight. | Trivandrum, Kottayam, Thrissur, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Agartala, Kozhikode, Kollam, Ernakulam, Kolkata (6) |

| Unlocking phase 5 | Navaratri (October 2020) | Sharada Navratri is observed in honor of Devi Durga and is celebrated for a period of nine days; the period is characterized by variety of festivities and celebrations in different parts of India. In the western Indian states of Maharashtra and Gujarat, a traditional Garba raas is organized with feasts, where people socialize and dance to thematic community songs and/or live music. | New Delhi, Mohali, Jalandhar, Amritsar, Ambala, Panchkula, Ludhiana, Kolkata, Gurugram, Gautam Buddha Nagar, Kullu, Manali, Hyderabad, Bengaluru, Mysuru, Surat, Mumbai, Lucknow, Pune, Ahmedabad, Vadodara, Nagpur, Guwahati, Dibrugarh, Patna, Prayagraj (94) |

| Unlocking phase 5 | Dusshera/Mysore Dushera/Vijayadashami (October 2020) | Dusshera is a major festival in North India, which is celebrated by the organization of pandals and fairs, community gatherings, the recitation of scriptures, the enactment of verses from Ramayana, and full-day or partial-day fasting rituals; it culminates on the 10th day with the burning of Ravana effigies. In Mysuru, the Mysuru Dussehra involves street processions with folk dances and depictions of fight scenes on a mass scale. | |

| Unlocking phase 5 | Durga Pooja (October 2020) | Celebrated to worship the Hindu deity Devi Durga. Pandal hopping, family and social gatherings, shopping, gifting, and feasts are usual features. | |

| Unlocking phase 6 | Deepavali (November 2020) | The celebrations include worshipping Hindu deities, family and social gatherings, shopping for utensils, ornaments, decorative items, and gifts, feasting, community gatherings, bursting crackers, and fairs. | New Delhi, Amritsar, Hyderabad, Ahmedabad, Nagpur, Mumbai, Madurai, Chennai, Ludhiana, Kanpur, Dhanbad, Ranchi, Mohali, Coimbatore, Tuticorin, Erode, Simla, Faridabad, Jaipur, Bhopal, Gurugram, Ernakulam, Thrissur (32) |

References

- Davies, K. Festivals post COVID-19. Leis. Sci. 2021, 43, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J. The effect of COVID-19 and subsequent social distancing on travel behavior. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 5, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calbi, M.; Langiulli, N.; Ferroni, F.; Montalti, M.; Kolesnikov, A.; Gallese, V.; Umiltà, M.A. The consequences of COVID-19 on social interactions: An online study on face covering. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bag, R.; Ghosh, M.; Biswas, B.; Chatterjee, M. Understanding the spatio-temporal pattern of COVID-19 outbreak in India using GIS and India’s response in managing the pandemic. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2020, 12, 1063–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehresmann, K.R.; Hedberg, C.W.; Grimm, M.B.; Norton, C.A.; Macdonald, K.L.; Osterholm, M.T. An outbreak of measles at an international sporting event with airborne transmission in a domed stadium. J. Infect. Dis. 1995, 171, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundlapalli, A.V.; Rubin, M.A.; Samore, M.H.; Lopansri, B.; Lahey, T.; McGuire, H.L.; Winthrop, K.L.; Dunn, J.J.; Willick, S.E.; Vosters, R.L.; et al. Influenza, winter olympiad, 2002. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botelho-Nevers, E.; Gautret, P. Outbreaks associated to large open air festivals, including music festivals, 1980 to 2012. Eurosurveillance 2013, 18, 20426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cariappa, M.P.; Singh, B.P.; Mahen, A.; Bansal, A.S. Kumbh Mela 2013: Healthcare for the millions. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2015, 71, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, V.T.; Gautret, P. Infectious diseases and mass gatherings. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2018, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newbold, C.; Jordan, J. Focus on World Festivals: Contemporary Case Studies and Perspectives; Goodfellow Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Venkata-Subramani, M.; Roman, J. The Coronavirus Response in India–World’s Largest Lockdown. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 360, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mair, J.; Smith, A. Events and sustainability: Why making events more sustainable is not enough. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1739–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F.N.; Rahman, A.F.; Iwuagwu, A.O.; Dalal, K. COVID-19 Transmission due to Mass Mobility Before and After the Largest Festival in Bangladesh: An Epidemiologic Study. INQUIRY J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2021, 58, 00469580211023464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, P.; Guo, S.; Chen, T. Correlation between travellers departing from Wuhan before the Spring Festival and subsequent spread of COVID-19 to all provinces in China. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, A.; Mathew, L.; Philip, S. As Kerala sees spike in Covid cases, minister says not reached peak yet. The Indian Express. 10 October 2020. Available online: https://indianexpress.com/article/india/kerala-covid-cases-spike-peak-shailaja-6719033 (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Taskin, B. Delhi markets are crowded with Diwali shoppers, there is no place for Covid rules. The Print. 3 November 2020. Available online: https://theprint.in/india/delhi-markets-are-crowded-with-diwali-shoppers-there-is-no-place-for-covid-rules/535291 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Mandal, S.; Arinaminpathy, N.; Bhargava, B.; Panda, S. Responsible travel to and within India during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Travel Med. 2021, 28, taab147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. District-Wise COVID-19 Test Positivity Rates. Available online: https://www.mohfw.gov.in (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Press Trust of India. ‘Jan Andolan’ launched to spread awareness among people about precautions against COVID-19. New Indian Express. 13 October 2020. Available online: https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2020/oct/13/jan-andolan-launched-to-spread-awareness-among-people-about-precautions-against-covid-19-2209760.html (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Jan Andolan’ campaign launched for COVID appropriate behavior. News18. 7 October 2020. Available online: https://www.news18.com/news/india/pm-modi-to-launch-jan-andolan-campaign-for-covid-19-appropriate-behaviour-2941555.html (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Office of Registrar of Newspapers for India. Available online: http://rni.nic.in/Default.aspx (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Ministry of Home Affairs. SOP on Preventive Measures to Contain Spread of COVID-19 in Offices. Available online: https://www.mha.gov.in/notifications/circulars-covid-19 (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Aggarwal, S.; Balaji, S.; Singh, T.; Menon, G.R.; Mandal, S.; Madhumathi, J.; Mahajan, N.; Kohli, S.; Kaur, J.; Singh, H.; et al. Association between ambient air pollutants and meteorological factors with SARS-CoV-2 transmission and mortality in India: An exploratory study. Environ. Health 2021, 20, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vong, S.; Kakkar, M. Monitoring COVID-19 where capacity for testing is limited: Use of a three-step analysis based on test positivity ratio. WHO South East Asia J. Public Health 2020, 9, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukumar, T. Year-end covid curve could be shaped by past festival lessons. Mint. 23 December 2020. Available online: https://www.livemint.com/science/health/year-end-covid-curve-could-be-shaped-by-past-festival-lessons-11608628003678.html (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Google COVID-19 Mobility Reports-2020. Available online: https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Saha, J.; Chouhan, P. Lockdown and unlock for the COVID-19 pandemic and associated residential mobility in India. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 104, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easter prayers on Facebook live amid corona lockdown. Deccan Chron. 12 April 2020. Available online: https://www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/in-other-news/120420/an-unconventional-easter-for-believers-this-year.html (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Drones, restrictions on outsiders among security protocol ahead of Ram temple event at Ayodhya. Hindustan Times. 2 August 2020. Available online: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/drones-restrictions-on-outsiders-among-security-protocol-ahead-of-ayodhya-event/story-s38mI5xYILtfqDqiWLICHJ.html (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Darshan on the wheels: Amid COVID-19, Kolkata offers drive-in Durga Puja. Hindustan Times. 14 August 2020. Available online: https://www.hindustantimes.com/travel/darshan-on-the-wheels-amid-covid-19-kolkata-offers-drive-in-durga-puja/story-nLEwhPhZ3u8tXwZyKgowfL.html (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Anand, S.N. Onam celebrations go virtual due to the pandemic. The Hindu. 27 August 2020. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/life-and-style/onam-goes-virtual-this-year/article32455967.ece (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Kapoor, R. India celebrates Diwali with more than 4 lakh active COVID-19 cases! But do we fear the infection at all? Times Now News. 14 November 2020. Available online: https://www.timesnownews.com/india/article/india-celebrates-diwali-with-more-than-4-lakh-active-covid-19-cases-but-do-we-fear-the-infection-at-all/681890 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Kundu, S. Empty pandals and virtual celebrations: Covid-19 dampens Kolkata’s spirit. Deccan Herald. 21 October 2020. Available online: https://www.deccanherald.com/national/east-and-northeast/durga-puja-2020-empty-pandals-and-virtual-celebrations-covid-19-dampens-kolkatas-spirit-905297.html (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Has coronavirus left India? Crowds of Diwali shoppers are leaving us anxious. The News18. 13 November 2020. Available online: https://www.news18.com/news/buzz/has-coronavirus-left-india-crowds-of-diwali-shoppers-are-leaving-us-anxious-3077717.html (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Pune: Housing society office-bearers booked for holding dandiya events amid Covid-19. India Today. 23 October 2020. Available online: https://www.indiatoday.in/cities/pune/story/pune-housing-society-office-bearers-booked-for-holding-dandiya-event-amid-covid-19-1734287-2020-10-23 (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Eager to celebrate Deepavali with family; Home travel of 3 lakh people: 3075 government buses run from Chennai on the 2nd day. Hindu Tamil. 13 November 2020. Available online: https://www.hindutamil.in/news/tamilnadu/601384-diwali-travel.html (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Domènech-Montoliu, S.; Pac-Sa, M.R.; Vidal-Utrillas, P.; Latorre-Poveda, M.; Del Rio-González, A.; Ferrando-Rubert, S.; Ferrer-Abad, G.; Sánchez-Urbano, M.; Aparisi-Esteve, L.; Badenes-Marques, G.; et al. Mass gathering events and COVID-19 transmission in Borriana (Spain): A retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahead of Ramzan, all rules of lockdown and social distancing tossed away as people throng to markets across India. OpIndia. 24 April 2020. Available online: https://www.opindia.com/2020/04/ramzan-markets-crowd-lockdown-social-distancing-flouted (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Tiwari, K. Bhagwan bharose Amdavad? Ahmedabad Mirror. 9 November 2020. Available online: https://ahmedabadmirror.indiatimes.com/ahmedabad/cover-story/bhagwan-bharose-amdavad/articleshow/79117718.cms (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Kolkata: Customers throng markets as Pujo fever trumps Covid fears. The Indian Express. 6 October 2020. Available online: https://indianexpress.com/photos/india-news/kolkata-customers-throng-markets-as-pujo-fever-trumps-covid-fears-6705379 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- State Bank of India. Four Months after Unlock: Silver Lining among Slowly Dissipating Dark Clouds. 2020. Available online: https://sbi.co.in/documents/13958/3312806/Four+months+after+Unlock-SBI+Report.pdf/0c8826a7-9aa4-d101-2cec-06c2cf307821?t=1602137343393 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Kaushik, S.; Kaushik, S.; Sharma, Y.; Kumar, R.; Yadav, J.P. The Indian perspective of COVID-19 outbreak. Virusdisease 2020, 31, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallapaty, S. India’s massive COVID surge puzzles scientists. Scientic American. 21 April 2021. Available online: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/indias-massive-covid-surge-puzzles-scientists (accessed on 3 May 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aggarwal, S.; Mahajan, N.; Kohli, S.; Balaji, S.; Singh, T.; Menon, G.R.; Rade, K.; Panda, S. Assessment of Community Behavior and COVID-19 Transmission during Festivities in India: A Qualitative Synthesis through a Media Scanning Technique. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610157

Aggarwal S, Mahajan N, Kohli S, Balaji S, Singh T, Menon GR, Rade K, Panda S. Assessment of Community Behavior and COVID-19 Transmission during Festivities in India: A Qualitative Synthesis through a Media Scanning Technique. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610157

Chicago/Turabian StyleAggarwal, Sumit, Nupur Mahajan, Simran Kohli, Sivaraman Balaji, Tanvi Singh, Geetha R. Menon, Kiran Rade, and Samiran Panda. 2022. "Assessment of Community Behavior and COVID-19 Transmission during Festivities in India: A Qualitative Synthesis through a Media Scanning Technique" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610157

APA StyleAggarwal, S., Mahajan, N., Kohli, S., Balaji, S., Singh, T., Menon, G. R., Rade, K., & Panda, S. (2022). Assessment of Community Behavior and COVID-19 Transmission during Festivities in India: A Qualitative Synthesis through a Media Scanning Technique. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610157