COVID-19 Lockdown in New Zealand: Perceived Stress and Wellbeing among International Health Students Who Were Essential Frontline Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

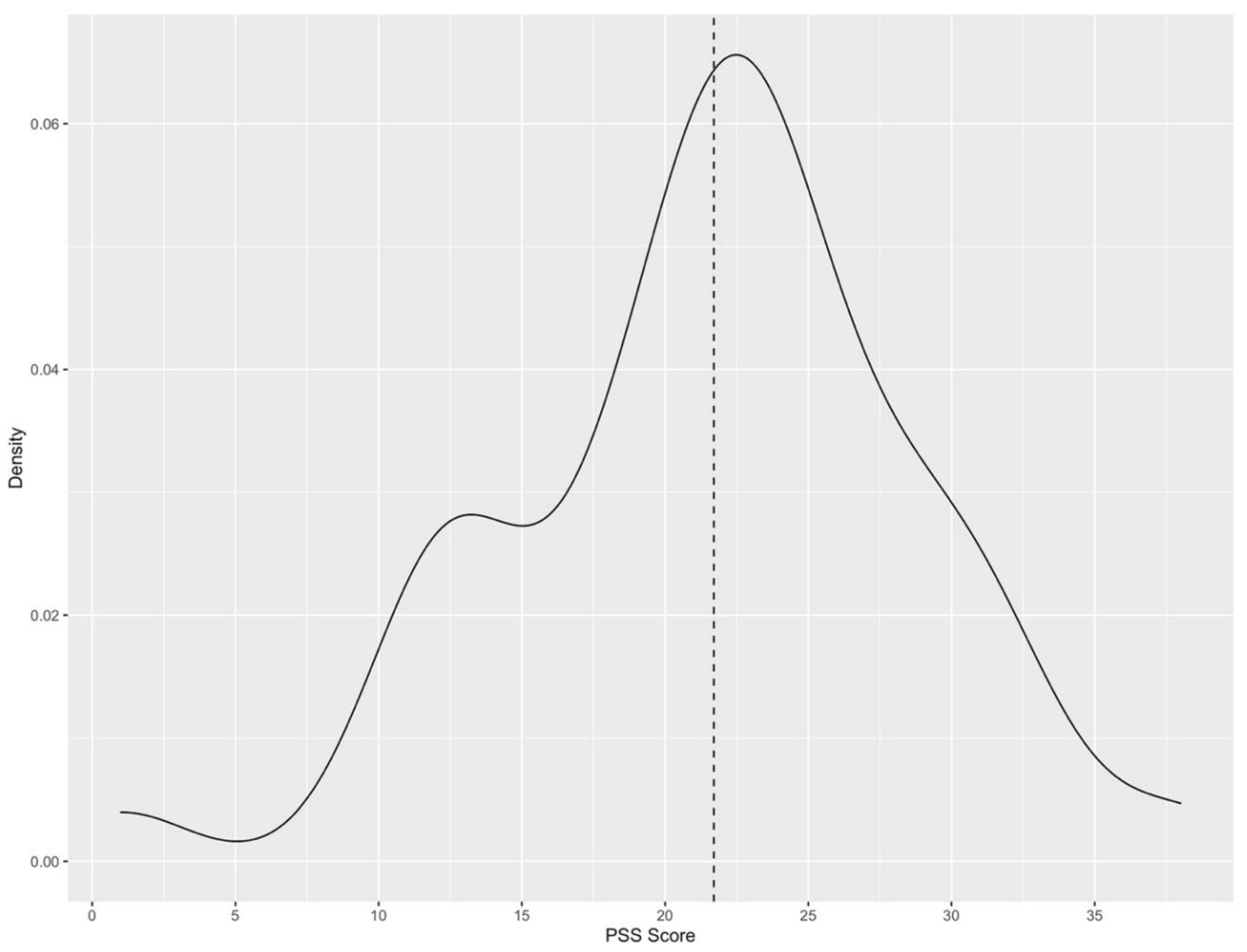

3.2. Descriptive Statistics of Perceived Level of Stress

3.3. Qualitative Data

3.4. Challenges and Sources of Stress

“…my spouse and younger daughter [were supposed to join me]. She is just 1 year [old]. We planned that they will come soon to join me but due to COVID-19 [sic] they can’t come here”.

“My paternal aunt’s family has difficulty due to COVID-19, as they were infected.”“Yes, my pregnant sister got COVID-19 after her visitation to gynaecologist.”

“My parents are diabetic and vulnerable to COVID infection. My grandmom is old and thus vulnerable too. It is very difficult for them to stay safe.”“The situation in my home country is getting worse by the day. It is a matter of personal concern to me since my mother is a doctor who is also at high-risk due to her age.”

“My kids are normally active, that’s why preventing them to go out is quite a challenge, they easily got bored during lockdown and increased the usage electronic devices. Adapting to new normal is quite challenging.”

“I am an essential worker and worried about catching COVID-19 infection from my work colleagues.”

“The organization have made proper arrangements in this regard [ensuring safety]. They provide face shields, PPE gowns, face-mask and others things”.

“I was definitely afraid to work in such an atmosphere because I am a student at the end and if something was to happen to me I would not have been able to pay the costs of treatment.”

“Didn’t have any [financial challenges] during the pandemic… as a healthcare worker, we were allowed to work more than 20 h hence [sic] it covered all my finances”.“ As I worked in full time in pandemic time, so [sic] I didn’t face any monetary issues.”

“Being busy [with work] was good allowed me to forget my issues (remembering of my kid back home).”

“It was a good experience to help elders and a rewarding job.”“… I was really proud of myself and it felt great to help people when they needed me the most.”

“It took [a] long time to get job because of COVID-19, as no face to face interview was possible. So, there was [a] delay in the process.”

“Hard to concentrate during online classes”

“The face to face interaction and discussion with course mates were [sic] limited. The library services were limited too.”

3.5. Institutional Support and Services Provided

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Beck, M.J.; Hensher, D.A. Insights into the impact of COVID-19 on household travel and activities in Australia—The early days of easing restrictions. Transp. Policy 2020, 99, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhama, K.; Khan, S.; Tiwari, R.; Sircar, S.; Bhat, S.; Malik, Y.S.; Singh, K.P.; Chaicumpa, W.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. Coronavirus Disease 2019-COVID-19. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00028-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szcześniak, D.; Gładka, A.; Misiak, B.; Cyran, A.; Rymaszewska, J. The SARS-CoV-2 and mental health: From biological mechanisms to social consequences. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharm. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 104, 110046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triggle, C.R.; Bansal, D.; Ding, H.; Islam, M.M.; Farag, E.A.B.A.; Hadi, H.A.; Sultan, A.A. A Comprehensive Review of Viral Characteristics, Transmission, Pathophysiology, Immune Response, and Management of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 as a Basis for Controlling the Pandemic. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 631139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udugama, B.; Kadhiresan, P.; Kozlowski, H.N.; Malekjahani, A.; Osborne, M.; Li, V.Y.C.; Chen, H.; Mubareka, S.; Gubbay, J.B.; Chan, W.C.W. Diagnosing COVID-19: The Disease and Tools for Detection. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 3822–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlmann, E.; Dussault, G.; Wismar, M. Health labour markets and the ‘human face’ of the health workforce: Resilience beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, iv1–iv2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC News. Coronavirus: New Zealand Marks 100 Days without Community Spread. BBC News, 9 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, D.F.; Brooks, P.M. On solutions to the shortage of doctors in Australia and New Zealand. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 190, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education in New Zealand. Ten Reasons to Study in New Zealand. 2021. Available online: https://www.studyinnewzealand.govt.nz/why-nz/quick-facts/ (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Martirosyan, N.M.; Bustamante, R.M.; Saxon, D.P. Academic and social support services for international students: Current practices. J. Int. Stud. 2019, 9, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipkins, H.C. International Education Contributes $5.1 Billion to New Zealand Economy. 2018. Available online: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/international-education-contributes-51-billion-new-zealand-economy (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Czeisler, M.; Wiley, J.F.; Facer-Childs, E.R.; Robbins, R.; Weaver, M.D.; Barger, L.K.; Czeisler, C.A.; Howard, M.E.; Rajaratnam, S.M. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during a prolonged COVID-19-related lockdown in a region with low SARS-CoV-2 prevalence. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 140, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.P.; Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; Pollak, T.A.; McGuire, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Zandi, M.S.; Lewis, G.; David, A.S. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, A.; Campbell, P.; Cheyne, J.; Cowie, J.; Davis, B.; McCallum, J.; McGill, K.; Elders, A.; Hagen, S.; McClurg, D.; et al. Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: A mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 11, CD013779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, V.; Bolanos, J.F.; Fiallos, J.; Strand, S.E.; Morris, K.; Shahrokhinia, S.; Cushing, T.R.; Hopp, L.; Tiwari, A.; Hariri, R.; et al. COVID-19: Review of a 21st Century Pandemic from Etiology to Neuro-psychiatric Implications. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 77, 459–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D. Who’s stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 1320–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, J.M.Y.; Ng, D.K.S. A study of the perceived stress level of university students in Hong Kong. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2016, 8, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzaz, Z.J.; Baig, M.; Al Alhendi, B.S.M.; Al Suliman, M.M.O.; Al Alhendi, A.S.; Al-Grad, M.S.H.; Qurayshah, M.A.A. Perceived stress, reasons for and sources of stress among medical students at Rabigh Medical College, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Par, M.; Hassan, S.A.; Uba, I.; Baba, M. Perceived stress among international postgraduate students in Malaysia. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2015, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- AlAteeq, D.A.; Aljhani, S.; AlEesa, D. Perceived stress among students in virtual classrooms during the COVID-19 outbreak in KSA. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2020, 15, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, E.D.; Peyer, K.L.; Doyle, K.A. A first look at perceived stress in southeastern university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, I.; Ochnik, D.; Çınar, O. Exploring Perceived Stress among Students in Turkey during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmer, T.; Mepham, K.; Stadtfeld, C. Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236337. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrozo-Pupo, J.C.; Pedrozo-Cortés, M.J.; Campo-Arias, A. Perceived stress associated with COVID-19 epidemic in Colombia: An online survey. Cad. Saude Publica 2020, 36, e00090520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabó, C.; Pukánszky, J.; Kemény, L. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Hungarian adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torales, J.; Ríos-González, C.; Barrios, I.; O’Higgins, M.; Ventriglio, A. Self-perceived stress during the quarantine of COVID-19 pandemic in Paraguay: An exploratory survey. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Arias, A.; Pedrozo-Pupo, J.C.; Herazo, E. Review of the COVID-19 Pandemic-related Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10-C). Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2021, 50, 156–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Ma, C. Australia’s Crisis Responses During COVID-19: The Case of International Students. J. Int. Stud. 2021, 11, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trice, A.G. Navigating in a multinational learning community: Academic departments’ responses to graduate international students. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2005, 9, 62–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Garcia, F.; Gongora-Gomez, O.; Gonzalez-Velazquez, V.E.; Pedraza-Rodriguez, E.M.; Zamora-Fung, R.; Lazo, L.A. Stress perceived by students of the medical sciences in Cuba toward the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of an online survey. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoke, M.; Mamo, G.; Abdu, S.; Terefe, B. Perceived Stress and Coping Strategies Among Undergraduate Health Science Students of Jimma University Amid the COVID-19 Outbreak: Online Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 639955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2016, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Sefcik, J.S.; Bradway, C. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A systematic review. Res. Nurs. Health 2017, 40, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotto, L.S. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods: Matthew B. Miles and A. Michael Huberman. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1986, 8, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, M.M. Investigator triangulation: A collaborative strategy with potential for mixed methods research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2016, 10, 228–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.D. Assessing Language Ability in the Classroom, 2nd ed.; Heinle ELT: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, M.J.; Brintz, C.E.; Birnbaum-Weitzman, O.; Penedo, F.J.; Gallo, L.C.; Gonzalez, P.; Gouskova, N.; Isasi, C.R.; Navas-Nacher, E.L.; Perreira, K.M.; et al. Factor structure of the Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS) across English and Spanish language responders in the HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psychol. Assess 2017, 29, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochnik, D.; Rogowska, A.M.; Kuśnierz, C.; Jakubiak, M.; Schütz, A.; Held, M.J.; Arzenšek, A.; Benatov, J.; Berger, R.; Korchagina, E.V.; et al. Mental health prevalence and predictors among university students in nine countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-national study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.; Poth, C. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design, 4th ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Martin School OM. India: Coronavirus Pandemic Country Profile. 2020. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/india?country (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Immigration, N.Z. Immigration New Zealand-COVID-19: Flexible Working Conditions for International Students Working in the Health Sector. 2021. Available online: https://www.immigration.govt.nz/about-us/COVID-19/in-new-zealand/student (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Ross, S.; Niebling, B.C.; Heckert, T.M. Sources of stress among college students. Coll Stud. J. 1999, 33, 312–317. [Google Scholar]

- Abid, T.; Zahid, G.; Shahid, N.; Bukhari, M. Online teaching experience during the COVID-19 in Pakistan: Pedagogy–technology balance and student engagement. Fudan J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 14, 367–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelehan, D.F. Students as Partners: A model to promote student engagement in post-COVID-19 teaching and learning. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education 2020, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, T.; Robinson, C.; Welch, A. The lived experiences of international students who’s family remains at home. J. Int. Stud. 2017, 7, 748–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, K.A. Indian international students in American higher education: An analysis of India’s cultural and socioeconomic norms in light of the international student experience. J. Stud. Pers. Assoc. Indiana Univ. 2010, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Savitsky, B.; Findling, Y.; Ereli, A.; Hendel, T. Anxiety and coping strategies among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020, 46, 102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Lei, W.; Xu, F.; Liu, H.; Yu, L. Emotional responses and coping strategies in nurses and nursing students during COVID-19 outbreak: A comparative study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Hu, K.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Gou, X.; Li, X. A qualitative study of the vocational and psychological perceptions and issues of transdisciplinary nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak. Aging 2020, 12, 12479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radio, N.Z. Countdown Give Essential Workers a Pay Rise, 2.49 pm 30 March 2020 edn; Radio New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Garrido-Moreno, A.; Martín-Rojas, R. The transformation of higher education after the COVID disruption: Emerging challenges in an online learning scenario. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetz, P.R.; Dawson, C.L.; Cullen, T.A. Social media use and the fear of missing out (FoMO) while studying abroad. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2015, 47, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Over the COVID-19 Lockdown Period: |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Main Themes: Challenges and Sources of Stress | Sub Themes | Student Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Familial Relationships | Separation from Family and Associated Disempowerment or Lack of Control | My children aged 12 and 8 were expected to join me or I was planning to travel back to India during the semester break in July, but neither of the plans worked since the borders were closed due to COVID-19. My husband and child wanted to join me very soon. It’s been 10 month[s] [since] we have applied for [a] visa, but due to COVID-19 [sic] the applications have not been [sic] processed and the borders are closed. It is very bad situation for us. I am living without my younger daughter and she also struggles without her mother (me). Yes, I want to bring my family over here. My husband is with me now. I planned to bring my children after finishing my course. With this COVID-19 [sic] issue I have no idea when I can bring my children. |

| Adapting to Increased Presence of Children | During lockdown, being with kids at home (out of school) was challenging. Difficult to manage children at home. | |

| Essential Work | Fear of Contracting the COVID-19 Virus | As essential work[ers] we have to work at [the] frontline, so when we go home there will be risk for infection to families. I was working as a cleaner in that period. So I was very afraid of work and being exposed to the sites. Stressing to get COVID-19 [sic] sometimes due to uncertainty about virus. I had some fear of using the public transport while going for my work… I think working as an essential worker was challenging. It’s good that I got the job but at the same time essential workers are at most risk of getting infected. |

| Workplace Intensity | It was very tough to work during this period because it was very difficult to manage the resident when they were not allowed to see their family. It was more stressful as resident of the facilities are locked down in house so their behaviours was [sic] more challenging. At first, it was difficult to adapt to the new environment and safety measures we had to take. I was constantly worried about the safety of the residents of my workplace… The residents of the rest home where I work were in emotional pain during lockdown as they could not meet their family members. It was heart breaking to see them suffer mentally and emotionally. They begged us to let them meet their family but we couldn’t do that due to restrictions. Some of them were affected so badly that their condition started to deteriorate. | |

| Finances | Financial Challenges | Difficult to find a job at first and was not able to open a bank account. I had to stay 2 weeks at home without pay after leaving one job to start another one. During the pandemic, we were unable to find part-time jobs, but FTS transfer was there so that we could manage our finances. |

| Study | Study-Related Challenges | Lack of concentration after few hours of virtual classes. Virtual classes were difficult to concentrate upon. Online classes were initially tough, but came out exciting later on. The live classroom delivery when compared to online delivery has twice the impact on students.so if the alert level is reduced, I always prefer to have live classes. Did online, but miss physical gathering [sic] and classmates. Being unable to seek in-person support from the tutors and library services was troublesome but got on track in a few weeks’ time. Lack of discussion about the topic with tutors and friends. Limited or no access to library due to COVID. Difficulties in assessments as lib [rary] and college face to face facilities were not working. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jagroop-Dearing, A.; Leonard, G.; Shahid, S.M.; van Dulm, O. COVID-19 Lockdown in New Zealand: Perceived Stress and Wellbeing among International Health Students Who Were Essential Frontline Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159688

Jagroop-Dearing A, Leonard G, Shahid SM, van Dulm O. COVID-19 Lockdown in New Zealand: Perceived Stress and Wellbeing among International Health Students Who Were Essential Frontline Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159688

Chicago/Turabian StyleJagroop-Dearing, Anita, Griffin Leonard, Syed M. Shahid, and Ondene van Dulm. 2022. "COVID-19 Lockdown in New Zealand: Perceived Stress and Wellbeing among International Health Students Who Were Essential Frontline Workers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159688

APA StyleJagroop-Dearing, A., Leonard, G., Shahid, S. M., & van Dulm, O. (2022). COVID-19 Lockdown in New Zealand: Perceived Stress and Wellbeing among International Health Students Who Were Essential Frontline Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159688