Protocol for a Delphi Consensus Study to Determine the Essential and Optional Ultrasound Skills for Medical Practitioners Working in District Hospitals in South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- a.

- Benefits of point of care ultrasound (POCUS)

- b.

- Drawbacks of POCUS

- c.

- Current practice

- d.

- Limitations identified in current literature and practice

2. Methods

- I.

- To determine the essential (mandatory) POCUS skills that all medical practitioners need in order to offer the required level of clinical services expected at district hospitals in South Africa.

- II.

- To determine the optional (relevant but geographically specific) POCUS skills that medical practitioners may require in order to optimally manage the geographically differentiated local burden of disease at some district hospitals in South Africa.

- a.

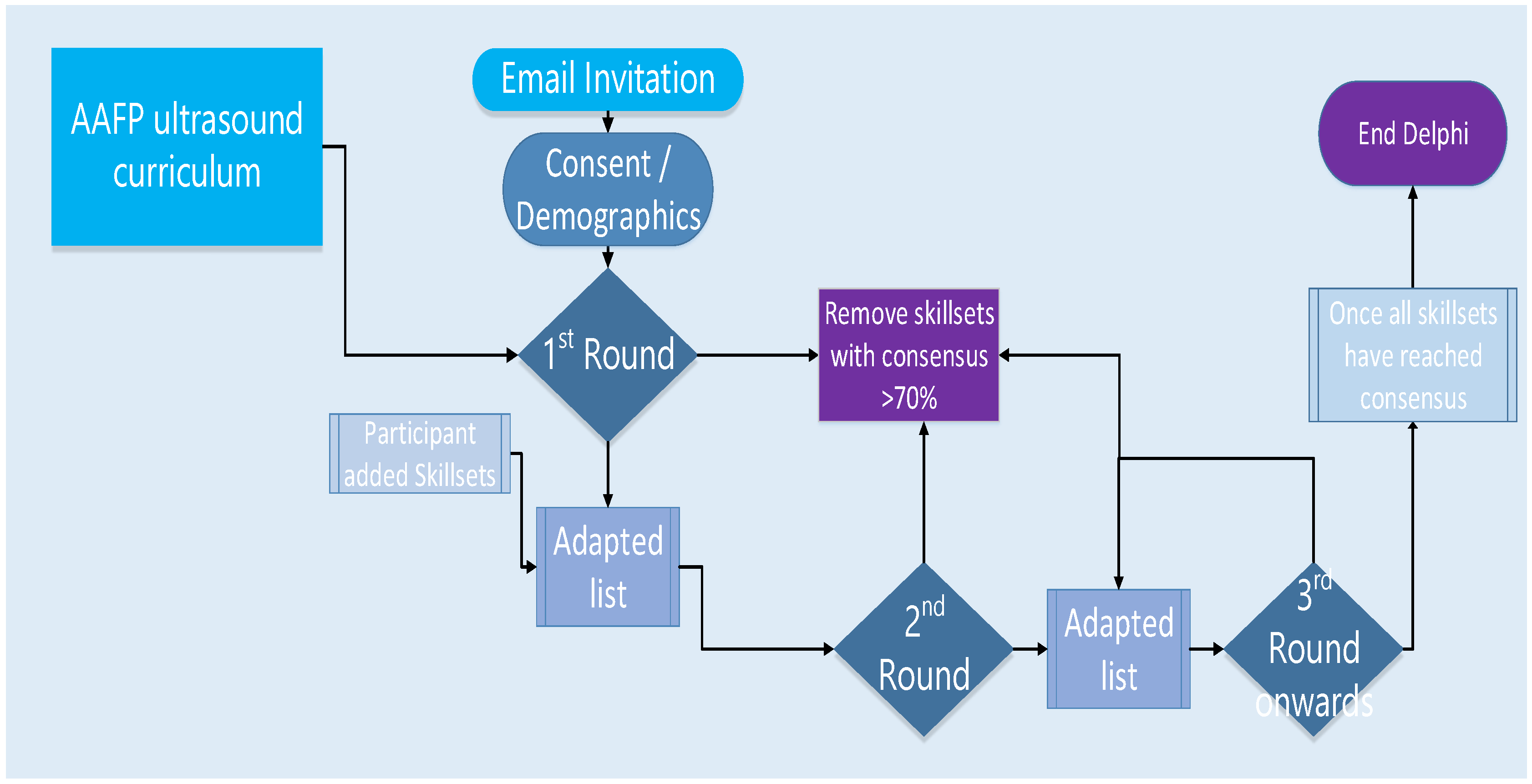

- Study Design

- b.

- Participants

- c.

- Starting questionnaire

- d.

- Implementation process

- e.

- Study schedule

- f.

- Ethical considerations

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| HIVAN | HIV associated Nephropathy |

| HOD | Head of Department |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| POCUS | Point of Care Ultrasound |

| POPIA | Protection of Personal Information Act |

| RUDASA | Rural Doctors Association of South Africa |

References

- Moore, C.; Copel, J. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dietrich, C.F.; Goudie, A.; Chiorean, L.; Cui, X.W.; Gilja, O.H.; Dong, Y.; Abramowicz, J.S.; Vinayak, S.; Westerway, S.C.; Nolsøe, C.P.; et al. Point of Care Ultrasound: A WFUMB Position Paper. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2017, 43, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smallwood, N.; Dachsel, M. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS): Unnecessary gadgetry or evidence-based medicine? Clin. Med. J. R. Coll. Physicians 2018, 18, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barjaktarevic, I.; Kenny, J.É.S.; Berlin, D.; Cannesson, M. The Evolution of Ultrasound in Critical Care: From Procedural Guidance to Hemodynamic Monitor. J. Ultrasound Med. 2020, 40, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbertson, E.A.; Hatton, N.D.; Ryan, J.J. Point of care ultrasound: The next evolution of medical education. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorentzen, T.; Nolsøe, C.P.; Ewertsen, C.; Nielsen, M.B.; Leen, E.; Havre, R.F.; Gritzmann, N.; Brkljacic, B.; Nürnberg, D.; Kabaalioglu, A.; et al. EFSUMB Guidelines on Interventional Ultrasound (INVUS), Part I: General aspects (long Version). Ultraschall Med. 2015, 36, E3–E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sorensen, B.; Hunskaar, S. Point-of-care ultrasound in primary care: A systematic review of generalist performed point-of-care ultrasound in unselected populations. Ultrasound J. 2019, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gretener, S.B.; Bieri, T.; Canova, C.R.; Engelberger, R.P.; Küpfer, S.; Lyrer, P.; Meuwly, J.Y.; Staub, D.; Thalhammer, C. Point-of-Care-Sonografie: Let’s keep it simple! Praxis 2015, 104, 1033–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Vieillard-Baron, A.; Malbrain, M.L.N.G. Emergency bedside ultrasound. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2019, 25, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopresti, C.M.; Jensen, T.P.; Dversdal, R.K.; Astiz, D.J. AAIM Perspectives Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Internal Medicine Residency Training: A Position Statement from the Alliance of Academic Internal Medicine. Am. J. Med. 2019, 132, 1356–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszynski, P.; Kim, D.; Liu, R.; Arntfield, R. A Multidisciplinary Response to the Canadian Association of Radiologists’ Point-of-Care Ultrasound Position Statement. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2020, 71, 136–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aletreby, W.; Alharthy, A.; Brindley, P.G.; Kutsogiannis, D.J.; Faqihi, F.; Alzayer, W.; Balhahmar, A.; Soliman, I.; Hamido, H.; Alqahtani, S.A.; et al. Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter Ultrasound for Raised Intracranial Pressure. J. Ultrasound Med. 2022, 41, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohseni-Bandpei, M.A.; Nakhaee, M.; Mousavi, M.E.; Shakourirad, A.; Safari, M.R.; Vahab Kashani, R. Application of ultrasound in the assessment of plantar fascia in patients with plantar fasciitis: A systematic review. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2014, 40, 1737–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bornemann, P.; Jayasekera, N.; Bergman, K.; Ramos, M.; Gerhart, J. Point-of-care ultrasound: Coming soon to primary care? J. Fam. Pract. 2018, 67, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gundersen, G.H.; Norekval, T.M.; Haug, H.H.; Skjetne, K.; Kleinau, J.O.; Graven, T.; Dalen, H. Adding point of care ultrasound to assess volume status in heart failure patients in a nurse-led outpatient clinic. A randomised study. Heart 2016, 102, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, P.; Bowra, J.; Lambert, M.; Lamprecht, H.; Noble, V.; Jarman, B. International federation for emergency medicine point of care ultrasound curriculum. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 17, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Constantine, E.; Levine, M.; Abo, A.; Arroyo, A.; Ng, L.; Kwan, C.; Baird, J.; Shefrin, A.E.; P2 Network Point-of-care Ultrasound Fellowship Delphi Group. Core Content for Pediatric Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Fellowship Training: A Modified Delphi Consensus Study. AEM Educ. Train. 2020, 4, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, I.W.; Arishenkoff, S.; Wiseman, J.; Desy, J.; Ailon, J.; Martin, L.; Otremba, M.; Halman, S.; Willemot, P.; Blouw, M. Internal Medicine Point-of-Care Ultrasound Curriculum: Consensus Recommendations from the Canadian Internal Medicine Ultrasound (CIMUS) Group. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 1052–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shah, S.; Noble, V.E.; Umulisa, I.; Dushimiyimana, J.M.; Bukhman, G.; Mukherjee, J.; Rich, M.; Epino, H. Development of an ultrasound training curriculum in a limited resource international setting: Successes and challenges of ultrasound training in rural Rwanda. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2008, 1, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maru, D.S.; Schwarz, R.; Jason, A.; Basu, S.; Sharma, A.; Moore, C. Turning a blind eye: The mobilization of radiology services in resource-poor regions. Glob. Health 2010, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Homar, V.; Gale, Z.K.; Lainscak, M.; Svab, I. Knowledge and skills required to perform point-of-care ultrasonography in family practice- A modified Delphi study among family physicians in Slovenia. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Løkkegaard, T.; Todsen, T.; Nayahangan, L.J.; Andersen, C.A.; Jensen, M.B.; Konge, L. Point-of-care ultrasound for general practitioners: A systematic needs assessment. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2020, 38, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nixon, G.; Blattner, K.; Muirhead, J.; Finnie, W.; Lawrenson, R.; Kerse, N. Scope of point-of-care ultraso 10.1071/HC18031und practice in rural New Zealand. J. Prim. Health Care 2018, 10, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sippel, S.; Muruganandan, K.; Levine, A.; Shah, S. Review article: Use of ultrasound in the developing world. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2011, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bélard, S.; Tamarozzi, F.; Bustinduy, A.L.; Wallrauch, C.; Grobusch, M.P.; Kuhn, W.; Brunetti, E.; Joekes, E.; Heller, T. Point-of-care ultrasound assessment of tropical infectious diseases-a review of applications and perspectives. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 94, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakovljevic, M.; Timofeyev, Y.; Ekkert, N.V.; Fedorova, J.V.; Skvirskaya, G.; Bolevich, S.; Reshetnikov, V.A. The impact of health expenditures on public health in BRICS nations. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaniuk, P.; Poznańska, A.; Brukało, K.; Holecki, T. Health System Outcomes in BRICS Countries and Their Association with the Economic Context. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanyonyi, S.; Mariara, C.; Vinayak, S.; Stones, W. Opportunities and Challenges in Realizing Universal Access to Obstetric Ultrasound in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ultrasound Int. Open 2017, 3, E52–E59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morewane, R.; Asia, B.; Asmall, S.; Steinhobel, R.; Mahomed, O.; Mahomed, S. Ideal Hospital Realisation and Maintenance Framework Manual; Report No.: Item 123. Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018. Available online: https://www.idealhealthfacility.org.za (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Soni, N.J.; Schnobrich, D.; Mathews, B.K.; Tierney, D.M.; Jensen, T.P.; Dancel, R.; Cho, J.; Dversdal, R.K.; Mints, G.; Bhagra, A.; et al. Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Hospitalists: A Position Statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. J. Hosp. Med. 2019, 14, E1–E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersen, C.A.; Holden, S.; Vela, J.; Rathleff, M.S.; Jensen, M.B. Point-of-care ultrasound in general practice: A systematic review. Ann. Fam. Med. 2019, 17, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arishenkoff, S.; Blouw, M.; Card, S.; Conly, J.; Gebhardt, C.; Gibson, N.; Lenz, R.; Ma, I.W.; Meneilly, G.S.; Reimche, L.; et al. Expert Consensus on a Canadian Internal Medicine Ultrasound Curriculum. Can. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 9, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Powell, C. The Delphi technique: Myths and realities. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003, 41, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ma, I.W.; Steinmetz, P.; Weerdenburg, K.; Woo, M.Y.; Olszynski, P.; Heslop, C.L.; Miller, S.; Sheppard, G.; Daniels, V.; Desy, J.; et al. The Canadian Medical Student Ultrasound Curriculum. J. Ultrasound Med. 2020, 39, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mash, R.; Steinberg, H.; Naidoo, M. Updated programmatic learning outcomes for the training of family physicians in South Africa. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2021, 63, a5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederberger, M. Delphi Technique in Health Sciences. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Province | University | No. |

|---|---|---|

| Western Cape | University of Cape Town (UCT) | 2 |

| Stellenbosch University (US) | 2 | |

| Eastern Cape | Walter Sisulu University (WSU) | 2 |

| KwaZulu-Natal | University of KwaZulu Natal (UKZN) | 2 |

| Free State | University of the Free State (UFS) | 2 |

| Gauteng | University of Witwatersrand (Wits) | 2 |

| University of Pretoria (UP) | 2 | |

| Sefako Makgotho Health Sciences University (SMU) | 2 | |

| Limpopo | University of Limpopo (UL) | 2 |

| Total | 18 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mans, P.-A.; Yogeswaran, P.; Adeniyi, O.V. Protocol for a Delphi Consensus Study to Determine the Essential and Optional Ultrasound Skills for Medical Practitioners Working in District Hospitals in South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159640

Mans P-A, Yogeswaran P, Adeniyi OV. Protocol for a Delphi Consensus Study to Determine the Essential and Optional Ultrasound Skills for Medical Practitioners Working in District Hospitals in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159640

Chicago/Turabian StyleMans, Pierre-Andre, Parimalaranie Yogeswaran, and Oladele Vincent Adeniyi. 2022. "Protocol for a Delphi Consensus Study to Determine the Essential and Optional Ultrasound Skills for Medical Practitioners Working in District Hospitals in South Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159640

APA StyleMans, P.-A., Yogeswaran, P., & Adeniyi, O. V. (2022). Protocol for a Delphi Consensus Study to Determine the Essential and Optional Ultrasound Skills for Medical Practitioners Working in District Hospitals in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159640