A Good App Is Hard to Find: Examining Differences in Racialized Sexual Discrimination across Online Intimate Partner-Seeking Venues

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Recruitment, Screening, and Consent

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Sociodemographics

2.4.2. Racialized Sexual Discrimination

2.4.3. White Superiority and Role Assumptions

2.4.4. Rejection

2.4.5. Physical Objectification

2.5. Data Collection and Cleaning

2.6. Data Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Analysis of Variance

4. Discussion

5. Implications

6. Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Badal, H.J.; Stryker, J.E.; DeLuca, N.; Purcell, D.W. Swipe right: Dating website and app use among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Bailey, G.; Hoots, B.E.; Xia, M.; Finlayson, T.; Prejean, J.; Purcell, D.W. Trends in internet use among men who have sex with men in the United States. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2017, 75, S288–S295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogels, E.A. 10 Facts about Americans and Online Dating. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/02/06/10-facts-about-americans-and-online-dating/ (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Grov, C.; Breslow, A.S.; Newcomb, M.E.; Rosenberger, J.G.; Bauermeister, J. Gay and Bisexual Men’s Use of the Internet: Research from the 1990s through 2013. J. Sex Res. 2014, 51, 390–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudelunas, D. There’s an App for that: The Uses and Gratifications of Online Social Networks for Gay Men. Sex. Cult. 2012, 16, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.W.; Serrano, P.A.; Bruce, D.; Bauermeister, J.A. The Internet’s Multiple Roles in Facilitating the Sexual Orientation Identity Development of Gay and Bisexual Male Adolescents. Am. J. Men’s Health 2016, 10, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pingel, E.S.; Bauermeister, J.A.; Johns, M.M.; Eisenberg, A.; Leslie-Santana, M. “A safe way to explore” reframing risk on the internet amidst young gay men’s search for identity. J. Adolesc. Res. 2013, 28, 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, C.; Birnholtz, J.; Abbott, C. Seeing and being seen: Co-situation and impression formation using Grindr, a location-aware gay dating app. New Media Soc. 2015, 17, 1117–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Maycock, B.; Burns, S. Your picture is your bait: Use and meaning of cyberspace among gay men. J. Sex Res. 2005, 42, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, R.M.; Harper, G.W. Racialized sexual discrimination (RSD) in the age of online sexual networking Are gay/bisexual men of color at elevated risk for adverse psychological health? Am. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 75, 504–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C.P. Anonymously hurting others online: The effect of anonymity on cyberbullying frequency. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2015, 4, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, C.T. The Gay Gayze: Expressions of Inequality on Grindr. Sociol. Q. 2019, 60, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauckner, C.; Truszczynski, N.; Lambert, D.; Kottamasu, V.; Meherally, S.; Schipani-McLaughlin, A.M.; Taylor, E.; Hansen, N. “Catfishing,” cyberbullying, and coercion: An exploration of the risks associated with dating app use among rural sexual minority males. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2019, 23, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.J.; Nakano, T.; Enomoto, A.; Suda, T. Anonymity and roles associated with aggressive posts in an online forum. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowlabocus, S. A Kindr Grindr: Moderating race (ism) in techno-spaces of desire. In Queer Sites in Global Contexts; Ramos, R., Mowlabocus, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C. No fats, femmes, or Asians: The utility of critical race theory in examining the role of gay stock stories in the marginalization of gay Asian men. Contemp. Justice Rev. 2008, 11, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.S.; Choi, K.H. Very few people say “No Whites”: Gay men of color and the racial politics of desire. Sociol. Spectr. 2018, 38, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.P.; Ayala, G.; Choi, K.-H. Internet Sex Ads for MSM and Partner Selection Criteria: The Potency of Race/Ethnicity Online. J. Sex Res. 2010, 47, 528–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, D.W. Anti-Asian sentiment amongst a sample of white Australian men on Gaydar. Sex Roles 2013, 68, 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coleman, B.R.; Collins, C.R.; Bonam, C.M. Interrogating Whiteness in Community Research and Action. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 67, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, D.W. The invisible Whiteness of being: Whiteness, White supremacy, White privilege, and racism. In Addressing Racism: Facilitating Cultural Competence in Mental Health and Educational Settings; Constantine, M.G., Sue, D.W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Callander, D.; Holt, M.; Newman, C. Just a preference: Racialised language in the sex-seeking profiles of gay and bisexual men. Cult. Health Sex. 2012, 14, 1049–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callander, D.; Holt, M.; Newman, C.E. ‘Not everyone’s gonna like me’: Accounting for race and racism in sex and dating web services for gay and bisexual men. Ethnicities 2016, 16, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callander, D.; Newman, C.E.; Holt, M. Is Sexual Racism Really Racism? Distinguishing Attitudes Toward Sexual Racism and Generic Racism Among Gay and Bisexual Men. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 13, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.M.; Reisner, S.L.; Dunham, E.; Mimiaga, M.J. Race-based sexual preferences in a sample of online profiles of urban men seeking sex with men. J. Urban Health 2014, 91, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cascalheira, C.J.; Smith, B.A. Hierarchy of Desire: Partner Preferences and Social Identities of Men Who Have Sex with Men on Geosocial Networks. Sex. Cult. 2020, 24, 630–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.A. “Personal preference” as the new racism: Gay desire and racial cleansing in cyberspace. Sociol. Race Ethn. 2015, 1, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.K. Structural dimensions of romantic preferences. Law Rev. 2007, 76, 2787–2819. [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren, A.L.; Menza, T.W.; LeGrand, S.; Muessig, K.E.; Bauermeister, J.A.; Hightow-Weidman, L.B. Stigma and mobile app use among young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2019, 31, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeown, E.; Nelson, S.; Anderson, J.; Low, N.; Elford, J. Disclosure, discrimination and desire: Experiences of Black and South Asian gay men in Britain. Cult. Health Sex. 2010, 12, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, L.; Forbes, T.D. Feeling Like a Fetish: Racialized Feelings, Fetishization, and the Contours of Sexual Racism on Gay Dating Apps. J. Sex Res. 2021, 59, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.A.; Valera, P.; Ventuneac, A.; Balan, I.; Rowe, M.; Carballo-Diéguez, A. Race-based sexual stereotyping and sexual partnering among men who use the internet to identify other men for bareback sex. J. Sex Res. 2009, 46, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calabrese, S.K.; Rosenberger, J.G.; Schick, V.R.; Novak, D.S. Pleasure, Affection, and Love Among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) versus MSM of Other Races: Countering Dehumanizing Stereotypes via Cross-Race Comparisons of Reported Sexual Experience at Last Sexual Event. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 44, 2001–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husbands, W.; Makoroka, L.; Walcott, R.; Adam, B.; George, C.; Remis, R.S.; Rourke, S.B. Black gay men as sexual subjects: Race, racialisation and the social relations of sex among Black gay men in Toronto. Cult. Health Sex. 2013, 15, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedi, S. Sexual Racism: Intimacy as a Matter of Justice. J. Politics 2015, 77, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daroya, E. Erotic capital and the psychic life of racism on Grindr. In The Psychic Life of Racism in Gay Men’s Communities; Riggs, D.W., Ed.; Lexington Books: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, R.M.; Harper, G.W. Toward a multidimensional construct of racialized sexual discrimination (RSD): Implications for scale development. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2021, 8, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambhani, Y.; Flynn, M.K.; Kellum, K.K.; Wilson, K.G. The Role of Psychological Flexibility as a Mediator Between Experienced Sexual Racism and Psychological Distress Among Men of Color Who Have Sex with Men. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, D.J.; Asakura, K.; George, C.; Newman, P.A.; Giwa, S.; Hart, T.A.; Souleymanov, R.; Betancourt, G. “Never reflected anywhere”: Body image among ethnoracialized gay and bisexual men. Body Image 2013, 10, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, D.; Hickson, D.A.; Callander, D.; Goodman, M.S.; Duncan, D.T. Racial Discrimination, Sexual Partner Race/Ethnicity, and Depressive Symptoms Among Black Sexual Minority Men. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 1799–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.-S.; Ayala, G.; Paul, J.P.; Boylan, R.; Gregorich, S.E.; Choi, K.-H. Stress and Coping with Racism and Their Role in Sexual Risk for HIV Among African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Latino Men Who Have Sex with Men. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 44, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hidalgo, M.A.; Layland, E.; Kubicek, K.; Kipke, M. Sexual Racism, Psychological Symptoms, and Mindfulness Among Ethnically/Racially Diverse Young Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Moderation Analysis. Mindfulness 2019, 11, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meanley, S.; Bruce, O.; Hidalgo, M.A.; Bauermeister, J.A. When young adult men who have sex with men seek partners online: Online discrimination and implications for mental health. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2020, 7, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, M.; Stainer, M.J.; Barlow, F.K. The “preference” paradox: Disclosing racial preferences in attraction is considered racist even by people who overtly claim it is not. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 83, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, R.M.; Bouris, A.M.; Neilands, T.B.; Harper, G.W. Racialized sexual discrimination (RSD) and psychological wellbeing among young sexual minority Black men (YSMBM) who seek intimate partners online. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suler, J. The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2004, 7, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonos, L. What Is Jack’d? The Gay Dating App, Explained. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/soloish/wp/2016/06/15/what-is-jackd-the-gay-dating-app-explained/(accessed on 15 June 2016).

- Chan, L.S.; Cassidy, E.; Rosenberger, J.G. Mobile dating apps and racial preferencing insights: Exploring self-reported racial preferences and behavioral racial preferences among gay men using Jack’d. Int. J. Commun. 2021, 15, 3928–3947. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, D.T.; Park, S.H.; Hambrick, H.R.; Ii, D.T.D.; Goedel, W.C.; Brewer, R.; Mgbako, O.; Lindsey, J.; Regan, S.D.; A Hickson, D. Characterizing Geosocial-Networking App Use Among Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Multi-City Cross-Sectional Survey in the Southern United States. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahmod, D.-E. Jack’d Goes after Grindr for Alleged Racism. The Bay Area Reporter. Available online: https://www.ebar.com/news/news//251703 (accessed on 8 November 2017).

- Grindley, L. Jack’d Attacks Grindr for Racist Profiles. The Advocate. Available online: https://www.advocate.com/business/2017/10/26/jackd-attacks-grindr-racist-profiles (accessed on 26 October 2017).

- Henry, P. Dear White Gay Men, Racism Is not “Just a Preference.” Them. Available online: https://www.them.us/story/racism-is-not-a-preference (accessed on 19 January 2018).

- Guobadla, O. Gay Communities are Rife with Racism. Removing Grindr’s Ethnicity Filters Won’t Fix That. GQ Magazine. Available online: https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/lifestyle/article/grindr-racism (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- West, T., III. White Gays, Please Stop Including BBC in Your Grindr Profile. Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/queens-of-the-bs/white-gays-please-stop-including-bbc-in-your-grindr-profile-322705be2de0 (accessed on 28 October 2020).

- Truong, K. Asian-American Man Plans Lawsuit to Stop ‘Sexual Racism’ on Grindr. NBCUniversal News Group. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/asian-american-man-threatens-class-action-discrimination-suit-against-grindr-n890946 (accessed on 17 July 2018).

- Lang, N. The Painful Reality of Sexual Racism in The Gay Community out Magazine. Available online: https://www.out.com/news-opinion/2017/5/15/truth-about-race-dating (accessed on 15 May 2017).

- Mastroyiannis, A. Gay Dating Apps: A Comprehensive Guide to Jack’d, Grindr, Hornet, Scruff and the Rest. Pink News. Available online: https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2018/03/05/best-gay-dating-apps-jackd-grindr-hornet-scruff/ (accessed on 3 March 2018).

- Bauermeister, J.A.; Pingel, E.; Zimmerman, M.; Couper, M.; Carballo-Dieguez, A.; Strecher, V.J. Data quality in HIV/AIDS web-based surveys: Handling invalid and suspicious data. Field Methods 2012, 24, 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fricker, R.D. Sampling methods for web and e-mail surveys. In The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods; Fielding, N., Lee, R.M., Blank, G., Eds.; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2008; pp. 195–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, R.M.; Harper, G.W. Racialized sexual discrimination (RSD) in online sexual networking: Moving from discourse to measurement. J. Sex Res. 2021, 58, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picardi, P. Scruff CEO: The Real Issue with Grindr is Way Bigger than Gay Marriage. Out Magazine. Available online: https://www.out.com/out-exclusives/2018/12/03/scruff-ceo-eric-silverberg-responds-grindr-president (accessed on 3 December 2018).

- Business Wire. Scruff Acquires Jack’d. Business Wire. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190709005872/en/SCRUFF-Acquires-Jack%E2%80%99d (accessed on 9 July 2019).

- Winder, T.J.; Lea, C.H. “Blocking” and “Filtering”: A commentary on mobile technology, racism, and the sexual networks of young black MSM (YBMSM). J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2019, 6, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categorical Variables | N (M) | % (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Orientation | |||||

| Gay | 387 | 70.6% | |||

| Bisexual | 89 | 16.2% | |||

| Other | 72 | 13.2% | |||

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 1 | 0.2% | |||

| High school graduate | 68 | 12.4% | |||

| Some college | 236 | 43.1% | |||

| College graduate | 155 | 28.3% | |||

| Post college | 88 | 16.1% | |||

| Primary | |||||

| App Grindr | 381 | 69.5% | |||

| Jack’d | 167 | 30.5% | |||

| Continuous Variables | M | SD | Min | Max | α |

| Age | 24.16 | 3.15 | 18 | 29 | — |

| RSD Subscales | |||||

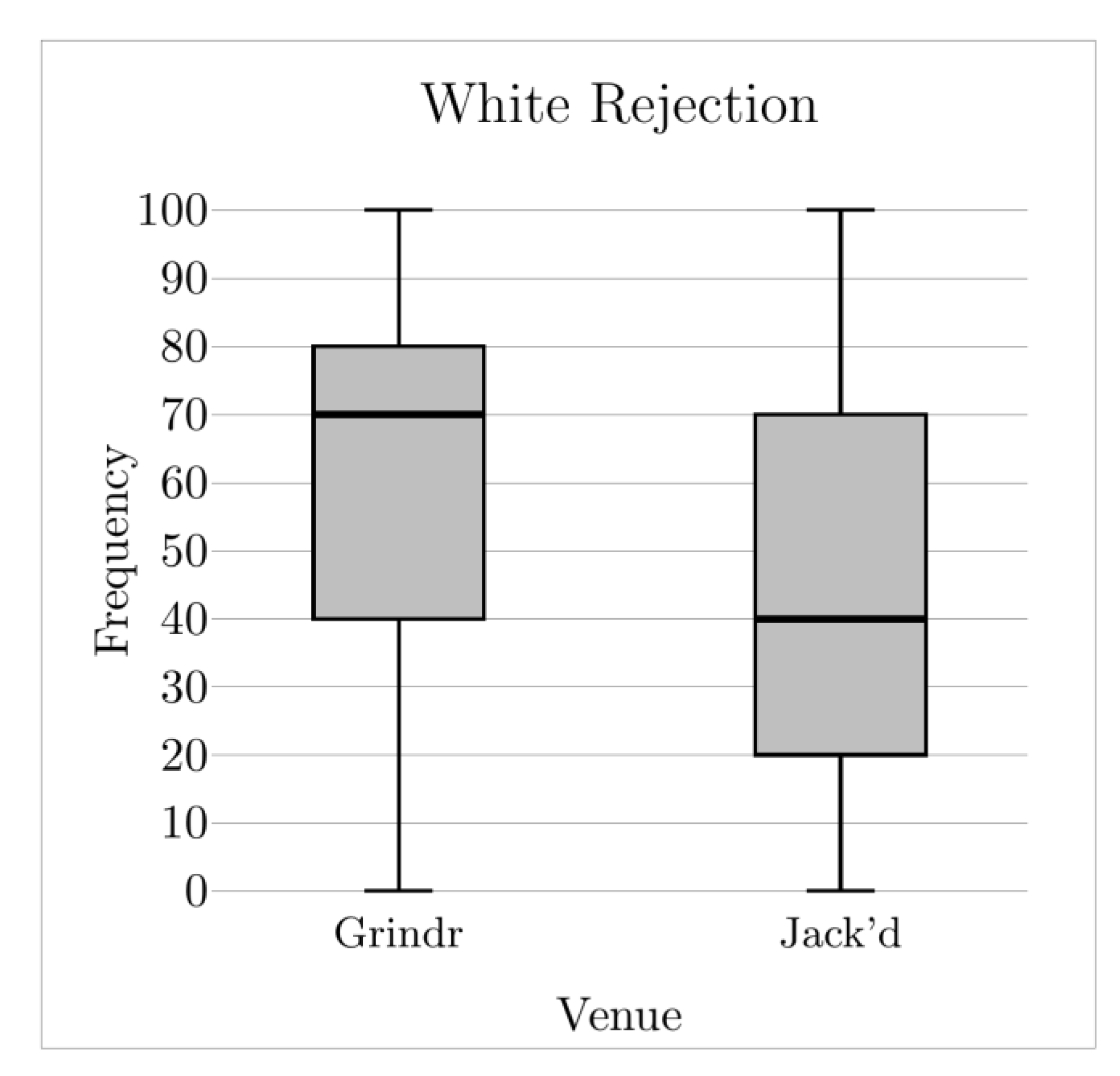

| White Rejection | 57.50 | 25.44 | 0 | 100 | 0.931 |

| Same-Race Rejection | 42.52 | 15.74 | 0 | 100 | 0.886 |

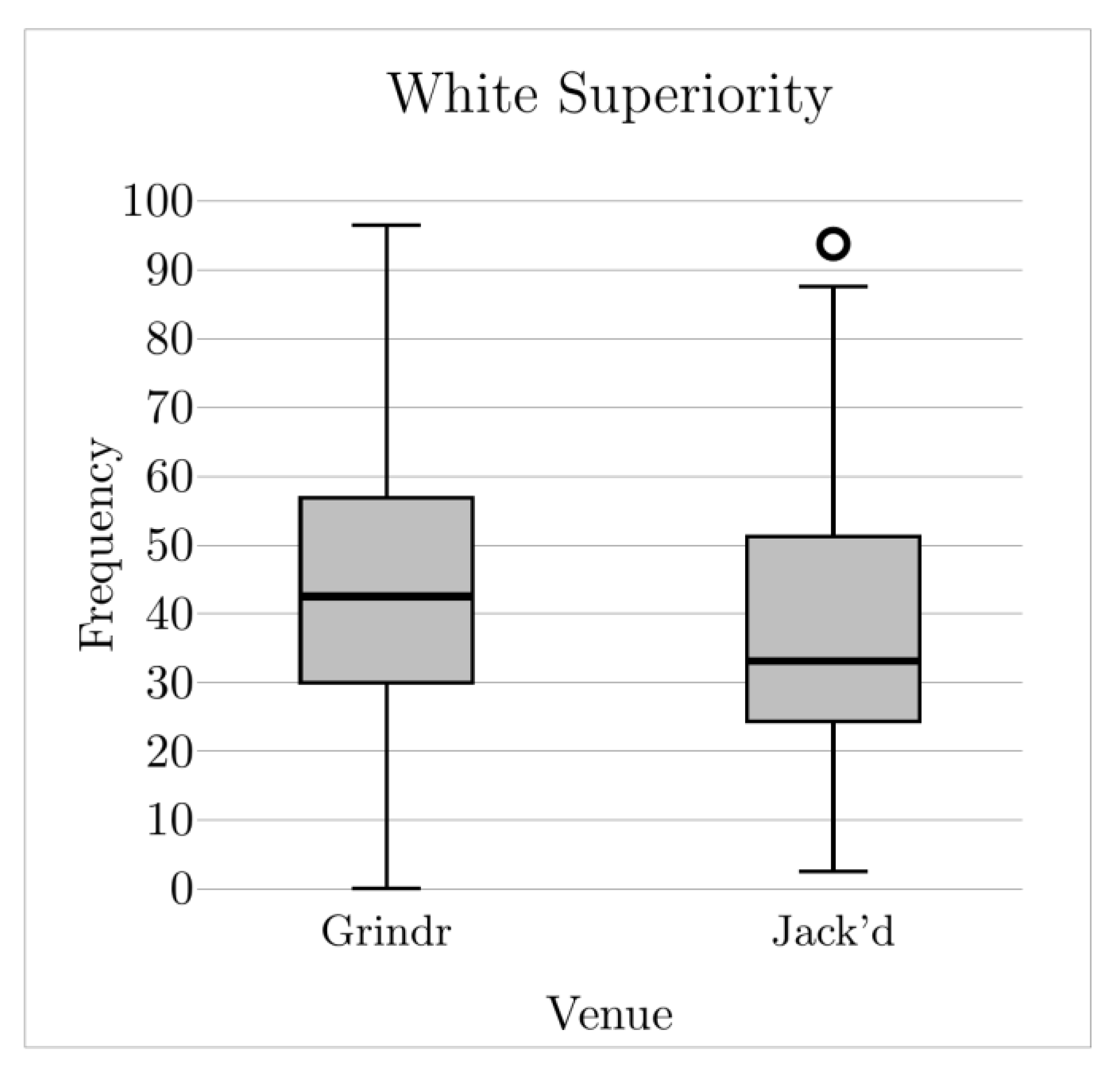

| White Superiority | 42.02 | 18.73 | 0 | 96.43 | 0.823 |

| White Physical Objectification | 54.36 | 25.62 | 0 | 100 | 0.801 |

| Same-Race Physical Objectification | 45.63 | 23.65 | 0 | 100 | 0.772 |

| Role Assumptions | 41.70 | 22.16 | 0 | 100 | 0.833 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. White Rejection | – | |||||

| 2. Same-Race Rejection | 0.21 ** | – | ||||

| 3. White Superiority | 0.46 ** | 0.22 ** | – | |||

| 4. White Physical Objectification | 0.11 * | 0.21 ** | 0.33 ** | – | ||

| 5. Same-Race Physical Objectification | −0.14 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.39 ** | – | |

| 6. Role Assumptions | 0.13 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.33 ** | – |

| Grindr Users (n = 381) | Jack’d Users (n = 167) | H | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White Rejection | 304.87 | 205.79 | 47.85 *** |

| Same-Race Rejection | 269.56 | 285.76 | 1.53 |

| White Superiority | 290.15 | 238.79 | 12.22 *** |

| White Physical Objectification | 271.75 | 280.77 | 0.39 |

| Same-Race Physical Objectification | 247.38 | 336.37 | 38.00 *** |

| Role Assumptions | 269.32 | 286.33 | 1.34 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wade, R.M.; Pear, M.M. A Good App Is Hard to Find: Examining Differences in Racialized Sexual Discrimination across Online Intimate Partner-Seeking Venues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148727

Wade RM, Pear MM. A Good App Is Hard to Find: Examining Differences in Racialized Sexual Discrimination across Online Intimate Partner-Seeking Venues. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(14):8727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148727

Chicago/Turabian StyleWade, Ryan M., and Matthew M. Pear. 2022. "A Good App Is Hard to Find: Examining Differences in Racialized Sexual Discrimination across Online Intimate Partner-Seeking Venues" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 14: 8727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148727

APA StyleWade, R. M., & Pear, M. M. (2022). A Good App Is Hard to Find: Examining Differences in Racialized Sexual Discrimination across Online Intimate Partner-Seeking Venues. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148727