Dental Implant Treatment in Patients Suffering from Oral Lichen Planus: A Narrative Review

Abstract

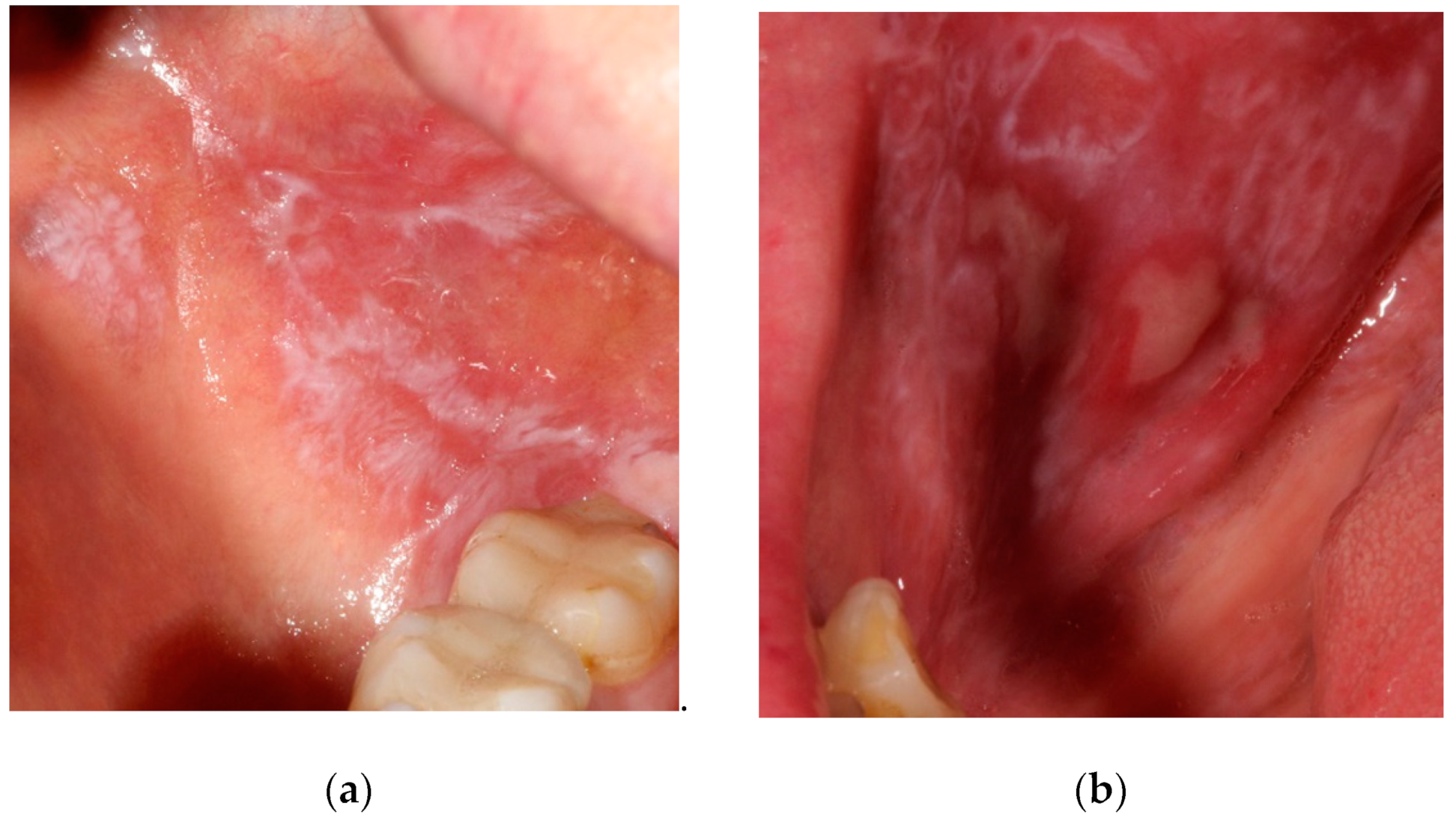

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alrashdan, M.S.; Cirillo, N.; McCullough, M. Oral lichen planus: A literature review and update. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2016, 308, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Moles, M.A.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; González-Ruiz, I.; González-Ruiz, L.; Ayén, Á.; Lenouvel, D.; Ruiz-Ávila, I.; Ramos-García, P. Worldwide prevalence of oral lichen planus: A systematic renvie and meta-analysis. Oral. Dis. 2020, 27, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pons-Fuster, A.; Jornet, P.L. Dental implants in patients with oral lichen planus: A long-term follow-up. Quintessence Int. 2014, 45, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mignogna, M.D.; Lo Russo, L.; Fedele, S. Gingival involvement of oral lichen planus in a series of 700 patients. J. Clin. Periodontol 2005, 32, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, M.; Troiano, G.; Cordaro, M.; Corsalini, M.; Gioco, G.; Lo Muzio, L.; Pignatelli, P.; Lajolo, C. Rate of malignant transformation of oral lichen planus: A systematic review. Oral Dis. 2019, 25, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, N.A.; Marchio, V.; Troiano, G.; Gasparro, R.; Balice, P.; Marenzi, G.; Laino, L.; Sammartino, G.; Iezzi, G.; Barone, A. Narrow-diameter versus standard-diameter implants placed in horizontally regenerated bone in the rehabilitation of partially and completely edentulous patients: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral. Implantol. 2022, 15, 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos, C.A.A.; Nunes, R.G.; Santiago-Júnior, J.F.; Marcela de Luna Gomes, J.; Oliveira Limirio, J.P.J.; Rosa, C.D.D.R.D.; Verri, F.R.; Pellizzer, E.P. Are implant-supported removable partial dentures a suitable treatment for partially edentulous patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Rinke, S.; Ohl, S.; Ziebolz, D.; Lange, K.; Eickholz, P. Prevalent of periimplant disease in partially edentulous patients: A practice-based cross-sectional study. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2011, 22, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Hirsch, J.M.; Lekholm, U.; Thomsen, P. Biological factors contributing to failures of osseointegrated oral implants. (II) Etiopathogenesis. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 1998, 106, 721–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugerman, P.; Savage, N.; Walsh, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, X.; Walsh, L.J.; Bigby, M. Oral lichen planus. Clin. Dermatol. 2000, 18, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugerman, P.B.; Barber, M.T. Patient selection for endosseous dental implants: Oral and systematic considerations. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2002, 17, 191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, M.; Thomsen, P.; Ericson, L.E.; Sennerby, L.; Lekholm, U. Histopathologic observations on late oral implant failures. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2000, 2, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oczakir, C.; Balmer, S.; Mericske-Stern, R. Implant-prosthodontic treatment for special care patients: A case series study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2005, 18, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Czerninski, R.; Kaplan, I.; Almoznino, G.; Maly, A.; Regev, E. Oral squamoous cell carcinoma around dental implants. Quintessence Int. 2006, 37, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gallego, L.; Junquera, L.; Baladrón, J.; Villarreal, P. Oral squamous cell carcinoma associated with symphyseal dental implants: An unusual case report. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2008, 139, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, E.; Spink, M.J.; Messina, A.M. Peri-implant squamous cell carcinoma: A case report with 5 years’follow-up. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 71, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moergel, M.; Karbach, J.; Kunkel, M.; Wagner, W. Oral squamous cell carcinoma in the vicinity of dental implants. Clin. Oral Investig. 2014, 18, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiser, V.; Abu-El Naaj, I.; Shlomi, B.; Fliss, D.M.; Kaplan, I. Primary oral malignancy imitating peri-implantitis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, K.; Moridera, K.; Sotsuka, Y.; Yamanegi, K.; Takaoka, K.; Kishimoto, H. Oral squamous cell carcinoma occurring secondary to oral lichen planus around the dental implant: A case report. Oral Sci. Int. 2019, 16, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Y. Implant-retained overdenture for a patients with severe lichen planus: A case report with 3 years’ follow-up and a systematic review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 77, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin-Cabezas, R. Peri-implantitis: Management in a patient with erosive oral lichen planus. A case report. Clin. Case Rep. 2020, 5, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.J.; Camisa, C.; Morgan, M. Implant retained overdentures for two patients with severe lichen planus: A clinical report. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003, 89, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichart, P.A. Oral lichen planus and dental implants. Report of 3 cases. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 35, 127–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerninski, R.; Eliezer, M.; Wilensky, A.; Soskolne, A. Oral lichen planus and dental implants—A retrospective study. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2013, 15, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, G.; Lopez-Pintor, R.M.; Arriba, L.; Torres, J.; de Vicente, J.C. Implant treatment in patients with oral lichen planus: A prospective-controlled study. Clin. Oral Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2012, 23, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Jornet, P.; Camacho-Alonso, F.; Sánchez-Siles, M. Dental implants in patients with oral lichen planus: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2014, 16, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboushelib, M.N.; Elsafi, M.H. Clinical management protocol for dental implants inserted in patients with active lichen planus. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 26, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, A.K.; Aboushelib, M.N.; Helal, M.H. Clinical management protocol for dental implants inserted in patients with active lichen planus. Part II 4-year follow-up. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitua, E.; Piñas, L.; Escuer-Artero, V.; Fernández, R.S.; Alkhraisat, M.H. Short dental implants in patients with oral lichen planus: A long-term follow-up. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 56, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Cruz, A.F.; Trindade, R.; Gomez, R.S. Dental implants in patients with oral lichen planus: A systematic review. Medicina 2020, 56, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anitua, E.; Alkhraisat, M.H.; Piñas, L.; Torre, A.; Eguia, A. Implant-prosthetic treatment in patients with oral lichen planus: A systematic review. Spec. Care Dentist. 2022, 42, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichart, P.A.; Schmidt-Westhausen, A.M.; Khongkhunthian, P.; Strietzel, F.P. Dental implants in patients with oral mucosal diseases—A systematic review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2016, 43, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guobis, Z.; Pacauskiene, I.; Astramskaite, I. General diseases influence on peri-implantitis development: A systematic review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Res. 2016, 7, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strietzel, F.P.; Schmidt-Westhausen, A.M.; Neumann, K.; Reichart, P.A.; Jackowski, J. Implants in patients with oral manifestations of autoimmune or muco-cutaneous diseases—A systematic review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2019, 24, e217–e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Xu, T.; Wang, X.; Qin, W.; Yu, T.; Luo, G. Is oral lichen planus a risk factor for peri-implant diseases? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrejon-Moya, A.; Saka-Herran, C.; Izquierdo-Gomez, K.; Mari-Roig, A.; Estrugo-Davesa, A.; Lopez-Lopez, J. Oral lichen planus and dental implants: Protocol and systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esimekara, J.-F.O.; Peres, A.; Courvoisier, D.S.; Scolozzi, P. Dental implants in patients suffering from autoimmune diseases: A systematic critical review. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Kunrath, M.F.; Gupta, S.; Lorusso, F.; Scarano, A.; Noumbissi, S. Oral Tissue Interactions and Cellular Response to Zirconia Implant-Prosthetic Components: A Critical Review. Materials 2021, 14, 2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiwara, N.; Masaki, C.; Mukaibo, T.; Kondo, Y.; Nakamoto, T.; Hosokawa, R. Soft tissue biological response to zirconia and metal implant abutments compared with natural tooth: Microcirculation monitoring as a novel bioindicator. Implant Dent. 2015, 24, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pandoleon, P.; Bakopoulou, A.; Papadopoulou, L.; Koidis, P. Evaluation of the biological behaviour of various dental implant abutment materials on attachment and viability of human gingival fibroblasts. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, T.F.; Anderson, J.; Bergholz, D.R.; Faiz, A.; Prasad, R.R. Gold Dental Implant-Induced Oral Lichen Planus. Cureus 2022, 14, e21852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Jornet, P.; Martinez-Beneyto, Y.; Nicolás, A.V.; Garcia, V.J. Professional attitudes toward oral lichen planus: Need for national and international guidelines. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2009, 15, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Moles, M.A.; Scully, C. Vesiculo-erosive oral mucosal disease-management with topical corticosteroids: (2) Protocols, monitoring of effects and adverse reactions, and the future. J. Dent. Res. 2005, 84, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.D.; Adams, A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 2006, 5, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Authors | Study Design | Patients | Implants (Number, Brand) | Control | Follow-Up Time (Months) | Implant Survival Rate (%) | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esposito et al. [12] | Cr | 1 female (erosive OLP), 69 y. | 2 Brånemark implants | None | 32, 60 | 0 | Implant failure in a patient with parafunction and poor bone quality. |

| Oczakir et al. [13] | Cr | 1 female with OLP, 74 y. | 4 implants (brand not reported) | None | 72 | 100 | No complications |

| Czerninski et al. [14] | Cr | 1 female (erosive OLP), 52 y. | 3 implants (brand not reported) | None | 36 | - | Oral squamous cell carcinoma developed around dental implants in a heavy smoker patient |

| Gallego et al. [15] | Cr | 1 female (reticular OLP), 81 y. | 2 implants (brand not reported) | None | 36 | 0 | Implant loss was caused by partial mandibular resection due to oral squamous cell carcinoma developed around one implant. |

| Marini et al. [16] | Cr | 1 female with plaque-type OLP, 51 y. | 2 implants (brand not reported) | None | 108 | 50 | Post-treatment evolution of OLP to oral squamous cell carcinoma with loss of implant |

| Moergel et al. [17] | Cr | 3 females with OLP, 54/69/80 y. | The number and the brand of implants not reported | None | 6-51 | - | Oral squamous cell carcinomas developed around dental implants, one patient had a history of cancer and the other two were smokers |

| Raiser et al. [18] | Cr | 2 females with OLP, 55/70 y. | 10 implants (brand not reported) | None | 96.3 | 100 | Oral squamous cell carcinoma around dental implants |

| Noguchi et al. [19] | Cr | 1 female with OLP, 78 y. | 4 implants (brand not reported) | None | 48 | 0 | Post-treatment evolution of OLP to oral squamous cell carcinoma with loss of implants |

| Fu et al. [20] | Cr | 1 female with erosive OLP, 65 y. | 4 NB implants | None | 36 | 100 | No complications |

| Martin-Cabezas [21] | Cr | 1 female with erosive OLP, 83 y. | 3 implants (brand not reported) | None | 12 | 100 | Peri-implantitis |

| Esposito et al. [22] | CS | 2 females (erosive OLP), 72/78 y. | 4 Straumann implants | None | 21 | 100 | No complications |

| Reichert et al. [23] | CS | 3 females (Pt I: reticular OLP, Pt II: reticular and atrophic OLP, Pt III: atrophic OLP without erosions), 63/68/79 y. | 8 implants (2 HATI, 1 ZL Microdent, 5 not reported) | None | Reported only for one Pt: 36 | 100 | Pt I: delayed wound healing; Pt II: bone resorption and gingivitis; Pt III: no complications |

| Czerninski et al. [24] | CCR | 14 patients: 11 females, 3 males (reticular, erosive and atrophic OLP), mean age 59.5 y. | 54 implants (brand not reported) | 15 controls: 11 females, 4 males with OLP, mean age 59.1 y., without dental implants | 12–24 | 100 in both groups | Bleeding on probing and gingivitis: nine implants in three patients |

| Hernández et al. [25] | CCP | 18 patients: 14 females and 4 males (erosive OLP), mean age 53.7 y. | 56 NB Ti-Unite implants | 18 controls: 12 females and 6 males without OLP, mean age 52.2 y., 62 implants | 53.5 (tests) 52.3 (controls) | 100 (tests) 96.77 (controls) | Peri-implant mucositis: 12 (43%) patients with OLP and 16 (57%) patients without OLP. Peri-implantitis: 5 (55.6%) patients with OLP and 4 (44.4%) patients without OLP. Two implants failed in the control group 32 and 46 months after loading. |

| López-Jornet et al. [26] | CCCS | Group I: 16 patients: 10 females, 6 males (11 reticular OLP, 5 atrophic erosive OLP), mean age 64.5 y. | 56 implants (brand not reported) | Group II: 16 controls: 11 females, 5 males (9 reticular OLP, 6 atrophic-erosive OLP), mean age 63 y., without dental implants. Group III: 16 controls: 8 females, 8 males without OLP, mean age 42, with 50 implants | 42 (12–120) | 96.4 (Group I) 92 (Group III) | Peri-implant mucositis: 17.8% in the OLP-implant group and 18% in the control group. Peri-implantitis: 25% in the OLP-implant group and 16% in the control group. Two mobile implants were found in Group I, and four mobile implants in Group III. |

| Aboushelib et al. [27] | CP | 23 patients: 12 females, 11 males with active OLP, mean age 56.7 y. | First set: 55 Zimmer implants Second set: 42 Zimmer implants (+oral corticosteroids and low-energy soft tissue laser irradiation at the implant insertion) | None | 3 36 | 23.6 100 | No osseointegration No complications |

| Khamis et al. [28] | CR | 20 patients with controlled OLP (by administration of low dose of corticoids) | The number and brand of implants not reported | 49 controls: 17 subjects without OLP without dental implants. 22 subjects with noncontrolled OLP with dental implants | 48 | 100 | Non controlled patients with OLP with dental implants exhibited increased marginal bone loss (up to 2.53 mm after 4 years) and recurrence of the oral lesions |

| Anitua et al. [29] | SCR | 23 patients: 20 females, 3 males (15 reticular OLP, 8 erosive OLP), mean age 58 y. | 66 BTI implants | None | 68 | 98.4 | Implant removal due to recurrent gingivitis in one patient |

| Authors | Year | Study Design | Type of Included Studies, Number of Patients, and Number of Implants | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fu et al. [20] | 2019 | Systematic review | 13 studies (9 case reports, 1 case-control prospective study, 1 case-control cross-sectional study, 1 case-control retrospective study, 1 cohort retrospective study) with 86 patients and 259 implants | “The survival rate of implants was 95.8% during a follow-up period ranging from 1 to 13 years. Dental implants seem to be an acceptable and reliable treatment option in patients with OLP.” |

| Chrcanovic et al. [30] | 2020 | Systematic review | 22 studies (15 case reports, 1 case-control retrospective study, 1 case-control cross-sectional study, 1 case-control prospective study, 4 cohort retrospective studies) with 230 patients and 615 implants | “The overall implant failure rate was 13.9% (85/610). In patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) the failure rate was 90.6% (29/32), but none of these implants lost osseointegration; instead, the implants were removed together with the tumor. One study (Aboushelib et al. 2017) presented a very high implant failure rate, 76.4% (42/55), in patients with “active lichen planus”, with all implants failing between 7–16 weeks after implant placement (…). If OSCC patients and the cases of the latter study are not considered, then the failure rate becomes very low (2.7%, 14/523). The time between implant placement and failure was 25.4 ± 32.6 months (range 1–112).” |

| Anitua et al. [31] | 2021 | Systematic review | 8 studies (2 case series, 1 case-control retrospcetive study, a case-control cross-sectinal study, 1 case-control prospective study, 3 cohort restrospective studies) that involved 141 patients and 341 implants | “The weighted mean follow-up was 38 months and the weighted mean survival of the implants 98.9%. No statistical differences were observed between cemented or screw retained prostheses and the materials employed or the technology to manufacture the prostheses.” |

| Reichart et al. [32] | 2016 | Systematic review | 9 studies (6 case reports, 1 case-control retrospective study, 1 case-control cross-sectional study, 1 case-control prospective study) | “After a mean observation period of 53·9 months, 191 implants in 57 patients with OLP showed a survival rate of 95·3% (SD ± 21.2). No strict contraindication for the placement of implants seems to be justified in patients with OLP (…). Implant survival rates are comparable to those of patients without oral mucosal diseases.” |

| Guobis et al. [33] | 2016 | Systematic Review | 3 case-control studies (1 retrospective, 1 prospective, 1 cross-sectional) with 106 patients and 278 implants | “Success of implant rehabilitation among treated OLP patients does not differ from the success rate in the general population. Implant survival and success rate was 100% vs. 96.8% in the control group.” |

| Strietzel et al. [34] | 2019 | Systematic review | 9 studies (4 case reports, 1 case-control retrospective study, 1 case-control cross-sectional study, 1 case-control prospective study, 2 cohort retrospective studies with 100 patients and 302 implants | ”After a mean follow-ip period of 44.6 months, a weighed mean values of implant survival rate of 98.3% was calculated (…) for patients with OLP (100 patients with 302 implants). Implant survival rates of patients affected are comparable to those of healthy patients.” |

| Xiong et al. [35] | 2020 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 2 studies (1 case-control prospective study and 1 case-control cross-sectional study) with 68 participants receiving 222 implants. | “Proportions of implants with peri-implant diseases (PIDs) between OLP and non-OLP groups were as follows: 19.6% (22/112) vs. 22.7% (25/110) for peri-implant mucositis and 17.0% (19/112) vs. 10.9% (12/110) for peri-implantitis. The meta-analysis revealed no recognizable difference in number of implants with PIDs (…) between OLP and non-OLP groups. Existing evidence does not support OLP as a suspected risk for peri-implant diseases.” |

| Torrejon-Moya et al. [36] | 2020 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 15 studies (10 case reports, 1 case-control retrospective study, 1 case-control cross-sectional study, 1 case-control prospective study, 1 cohort retrospective study, 1 cohort prospective study) with 110 patients. 3 studies included in meta-analysis (48 patients with OLP and 49 patients without OLP) | “According to the results of the meta-analysis, with a total sample of 48 patients with OLP and 49 patients without OLP, an odds ratio of 2.48 (95% CI 0.34–18.1) was established, with an I2 value of 0%. According to the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) criteria, level A can be established to conclude that patients with OLP can be rehabilitated with dental implants.” |

| Esimekara et al. [37] | 2022 | Systematic critical review | 11 studies (5 case reports, 1 case-control retrospective study, 1 case-control cross sectional study, 1 case-control prospective study, 2 cohort retrospective studies, 1 cohort prospective study) | “This review suggested that dental implants may be considered as a safe and viable therapeutic option in the management of edentulous patients suffering from autoimmune diseases. (…) Results showed that dental implant survival rates were comparable to those reported in the general population. However, patients with (…) erosive OLP were more susceptible to developing peri-mucositis and increased marginal bone loss.” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Górski, B. Dental Implant Treatment in Patients Suffering from Oral Lichen Planus: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148397

Górski B. Dental Implant Treatment in Patients Suffering from Oral Lichen Planus: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(14):8397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148397

Chicago/Turabian StyleGórski, Bartłomiej. 2022. "Dental Implant Treatment in Patients Suffering from Oral Lichen Planus: A Narrative Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 14: 8397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148397

APA StyleGórski, B. (2022). Dental Implant Treatment in Patients Suffering from Oral Lichen Planus: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148397