The Health Needs of Regionally Based Individuals Who Experience Homelessness: Perspectives of Service Providers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“if their current living arrangement is in a dwelling that is inadequate; or has no tenure, or if their initial tenure is short and not extendable; or does not allow them to have control of, and access to space for social relations”.[6]

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis: Coding and Thematic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Health Issues

3.1.1. Mental Health Conditions

“Particularly from a perspective around suicide, a multitude of social factors which lead to an inability to cope, and then feelings of disconnection which comes from those experiences”.(P2)

3.1.2. Physical Health Conditions

“Especially if there’s dual diagnosis. If they’re [involved with both] drug and alcohol use. They fall through the gaps because neither side wants to pick them up”.(P11)

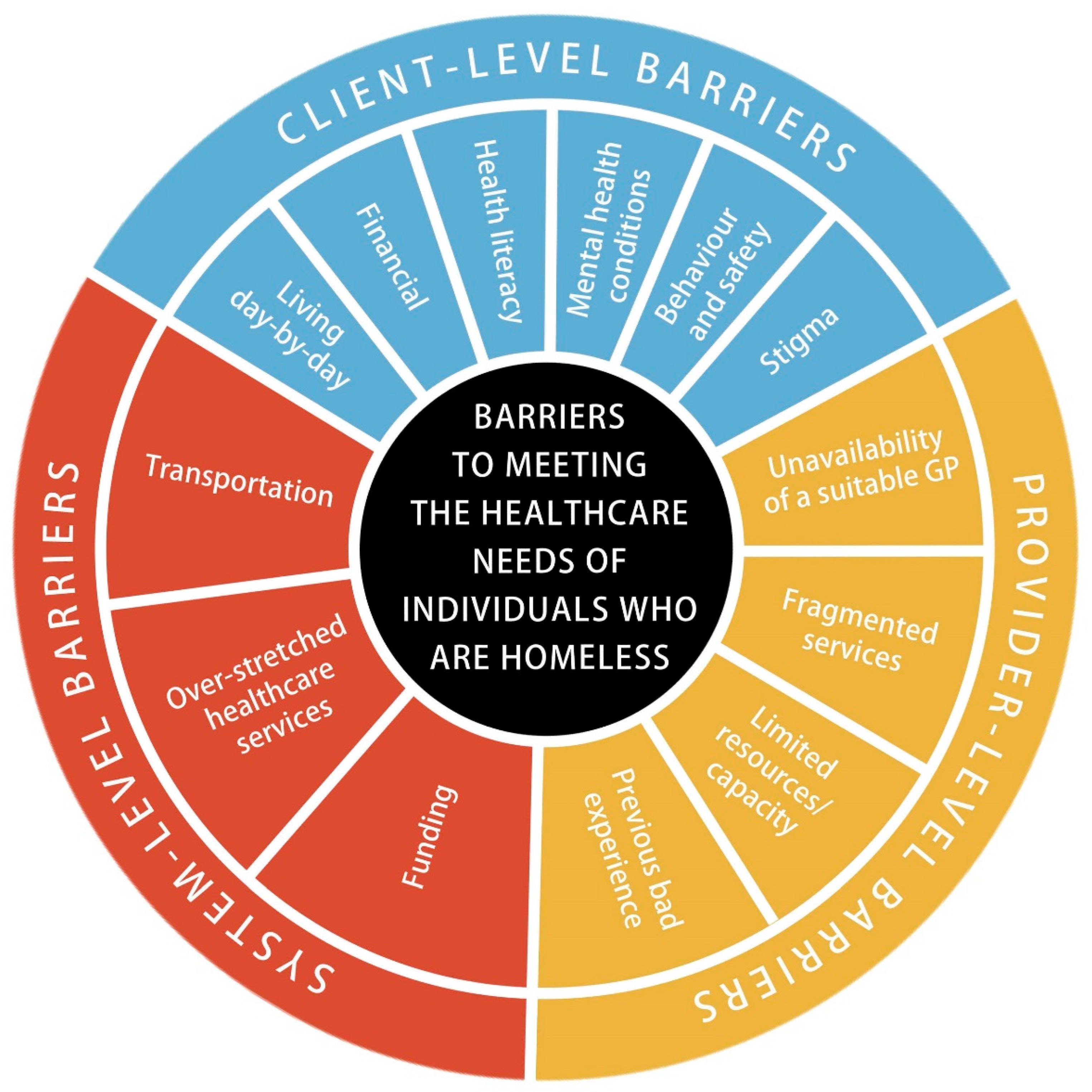

3.2. Barriers to Meeting the Healthcare Needs of Individuals Experiencing Homelessness

3.2.1. Client-Level Barriers

Living Day-by-Day

“If a receptionist says there is an appointment in a weeks’ time....it is often missed or completely forgotten about, cause it’s just too hard, they’re not thinking that far ahead, they’re just thinking about getting through that day really”.(P8)

Financial

Health Literacy

“The language barrier… [the use of big words and all that. They [the individual experiencing homelessness] just sit there and go ‘yeah, yeah, yeah’. And then I walk out with them and say, ‘did you understand?’ and they say ‘no, not really’. It’s just too hard”.(P9)

Mental Health Conditions

“We do have some that … been banned from some of those places [health care providers]. And that can be [due to] mental health problems, been too long without meds... so that can cause some issues”.(P9)

Behaviour and Safety

“Unfortunately, some have developed anger issues …. There are a lot of doctors that they have been known to say “well, you’re not coming back here anymore”… Some of them [the individuals experiencing homelessness] have gotten to a point where they just don’t know where to go anymore”.(P8)

Stigma

3.2.2. Provider-Level Barriers

Lack of Availability of a Suitable Doctor

Fragmented Services

“To get into certain programs you need to get referred through this department, but to get into that department you have to be referred to another department…..it’s not quite as streamlined and not as easy to get people into the programs they need to be in”.(P1)

Limited Resources/Capacity

“There’s just not that capacity to sit down with someone for 3, 4 h and talk through stuff, sometimes it’s just a 20-min appointment”.(P1)

Previous Bad Experiences

3.2.3. System-Level Barriers

Over-Stretched Healthcare Services

“The other choice, because it is the only choice, is the emergency department … they can’t get their needs met elsewhere. I heard … of someone who … needed to get a repeat prescription, but because they hadn’t been for a little bit to the doctor, they had to make an appointment to re-visit … before the script could be written … couldn’t get an appointment, couldn’t get in … ended up presenting at the emergency department to try and get that need met … So, the choice is the emergency department, because there is no other choice for some people to have their needs met”.(P6)

Transportation

“He needs to scoot (motorised wheelchair) all the way out … and all the way back (12 kms each way). He has to charge it when he’s out there, so he can get back. That’s a long way to go … let alone the safety aspects, I see him on the road sometimes … that’s not a good thing to have to do all that”.(P5)

Funding

3.3. Approaches to Health Care

“In the early days, we used to have a doctor that would come over once a week to see any residents that need assistance, the doctor retired, and the service stopped. In today’s climate to have a nurse or a doctor available to visit on a weekly basis would have so many benefits to our service and take the pressure of other services”.(P8)

“It was a case management model. You had social workers, but you had community workers as well, TAFE trained. That would make themselves very available to clients, booking appointments, taking them to appointments, making sure their needs were met, liaising with services, building a team. And we don’t have a service that does that anymore …. I think that we really need to turn it on its head and go out to the patient and make ourselves more accessible”.(P2)

4. Discussion

4.1. Potential Approaches to Health Care

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Council of Social Services. Poverty in Australia 2016; Australian Council of Social Services: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- AIHW. Health of People Experiencing Homelessness; Australian Institute for Health and Welfare: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pleace, N.; Baptista, I.; Benjaminsen, L.; Geertsema, V.; O’Sullivan, E.; Teller, N. European Homelessness and COVID 19; European Observatory on Homelessness: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- AIHW. Australia’s Welfare 2017; Australian Institute for Health and Welfare: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ABS. Census of Population and Housing: Estimating Homelessness Methodology; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ABS. Factsheet: Homelessness- in Concept and in Some Measurement Contexts; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- AIHW. Homelessness and Homelessness Services; Australian Institute for Health and Welfare: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ABS. Census of Population and Housing: Estimating Homelessness, 2011; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, T. Efforts escalate to protect people experiencing homelessness from COVID-19 in UK. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 447–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsai, J.; Wilson, M. COVID-19: A potential public health problem for homeless populations. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, E186–E187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIHW. Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence Service Responses in the Time of COVID-19; Australian Institute for Health and Welfare: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, K.; Morley, C.; Warren, S.; Ryan, V.; Ball, M.; Clarke, J.; Vitis, L. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Australian domestic and family violence services and their clients. Aust. J. Soc. Issues 2021, 56, 539–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIHW. Specialist Homelessness Services Annual Report 2018–2019; Australian Institute for Health and Welfare: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fitz-Gibbon, K.; Meyer, S. Coronavirus: Fear of Family Violence Spike as COVID-19 Impact Hits Household; Monash University: Clayton, VIC, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, D.; Lester, L. Establishing the number of older women at risk of homelessness. Parity 2020, 33, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, S.; Geddes, J.; Kushel, M. The health of people experiencing homelessness in high-income countries. Descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet 2014, 384, 1529–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stafford, A.; Wood, L. Tackling health disparities for people who are homeless? Start with social determinants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Dongen, S.; Straaten, B.; Wolf, J.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.; Van Der Heide, A.; Rietjens, J.; Van de Mheen, D. Self-reported health, healthcare service use and health-related needs: A comparison of older and younger people experiencing homelessness. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 27, e379–e388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Easterday, A.; Driscoll, D.; Ramaswamy, S. Rural homelessness: Its effect on healthcare access, healthcare outcomes, mobility, and perspectives of novel technologies. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 2019, 28, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwell-Sutton, T.; Fok, J.; Albanese, F.; Mathie, H.; Holland, R. Factors associated with access to care and healthcare utilization in the homeless population of England. J. Public Health 2016, 39, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Keogh, C.; O’Brien, K.; Hoban, A.; O’Carroll, A.; Fahey, T. Health and use of health services of people who are homeless and at risk of homelessness who receive free primary health care in Dublin. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wood, L.; Flatau, P.; Zeretzky, K.; Foster, S.; Vallesi, S.; Miscenko, D. What Are the Health and Social Benefits of Providing Housing and Support to Formerly People Experiencing Homelessness? AHURI Final Report No.265; Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.; Burns, T. Health interventions for people who are homeless. Lancet 2014, 384, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medcalf, P.; Russell, G. Homeless healthcare: Raising the standards. Clin. Med. 2014, 14, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henwood, B.; Lahey, J.; Rhoades, H.; Winetrobe, H.; Wenzel, S. Examining the health status of homeless adults entering permanent supportive housing. J. Public Health 2017, 40, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luchenski, S.; Maguire, N.; Aldridge, R.W.; Hayward, A.; Story, A.; Perri, P.; Withers, J.; Clint, S.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Hewett, N. What works in inclusion health: Overview of effective interventions for marginalized and excluded populations. Lancet 2018, 391, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Wood, N.; Vallesi, S.; Stafford, A.; Davies, A.; Cumming, C. Hospital collaboration with a Housing First program to improve health outcomes for people experiencing homelessness. Hous. Care Support 2019, 22, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrun, L.; Baggett, T.; Jenkins, D.; Sripipatana, A.; Charma, R.; Hayashi, A.; Daly, C.; Ngo-Metzger, Q. Health status and health care experiences among homeless patients in Federally supported health centres: Findings from the 2009 patient survey. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 992–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roche, M.A.; Duffield, C.; Smith, J.; Kelly, D.; Cook, R.; Bichel-Findlay, J.; Saunders, C.; Carter, D.J. Nurse-led primary health care for homeless men: A multimethods descriptive study. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2018, 65, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stenius-Ayoade, A.; Haaramo, P.; Erkkila, E.; Marola, N.; Nousianien, K.; Wahlbeck, K.; Eriksson, J. Mental disorders and the use of primary health care services amoung homeless shelter users in the Helsinki metropolitan area, Finland. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fischer, P.J. Estimating prevalence of alcohol, drug and mental health problems in the contemporary homeless population: A review of the literature. Contemp. Drug Probl. 1989, 16, 333–390. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.; Tyler, K.; Write, J. The new homelessness revisited. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 36, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shlay, A.; Rossi, P. Social science research and contemporary studies of homelessness. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1992, 18, 129–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Zhou, P. The health issues of the homeless and the homeless issues of the ill-health. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 69, 100677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoo, N.; Motamed, M.; Mikoo, M.; Neilson, E.; Saddicha, S.; Krausz, M. Chronic Physical Health Conditions among Homeless. J. Health Disparities Res. Pract. 2015, 8, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Swabri, J.; Uzor, C.; Laird, E.; O’Carroll, A. Health status of homeless in Dublin: Does the mobile health clinic improve access to primary healthcare for its users? Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 188, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upshur, C.; Jenkins, D.; Weinreb, L.; Gelberg, L.; Orvek, E. Prevalence and predictors of substance use disorders among homeless women seeking primary care: An 11-site survey. Am. J. Addict. 2017, 26, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canham, S.; Davidson, S.; Custodio, K.; Mauboules, C.; Good, C.; Wister, A.; Bosma, H. Health supports needed for homeless persons transitioning from hospitals. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 27, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davies, A.; Wood, L. Homelessness health care: Meeting the challenges of providing primary care. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 209, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, S.; Laursen, T.; Hjorthoj, C.; Nordentoft, M. Homelessness as a predictor of mortality: An 11- year register-based cohort study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, B.; Wood, L.; Vallesi, S.; Macfarlane, S.; Currie, J.; Haigh, F.; Gill, K.; Wilson, A.; Harris, P. Integrating healthcare services for people experiencing homelessness in Australia: Key issues and research principles. Integr. Healthc. J. 2022, 4, e000065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D‘Suza, M.; Mirza, N. Towards equitable healthcare access: Community participatory research exploring unmet healthcare needs of homeless individuals. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 2021, 08445621211032136. [Google Scholar]

- Barile, J.; Parker, A. Identifying and understanding gaps in services for adults experiencing homelessness. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 30, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickasch, B.; Marnocha, S. Healthcare experiences of the homeless. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2009, 21, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, N.; Hossain, R.; Moore, M.; Milo, M.; Brown, A. Health care while homeless: Barriers, facilitators and the lived experiences of homeless individuals accessing health care in a Canadian regional municipality. Qual. Health Res. 2019, 29, 1839–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, S.; Dunn, M.; Huff, J.; Psychiatric Outreach Team. Examining Health literacy levels in homeless persons and vulnerably housed persons with mental health disorders. PubMed 2019, 56, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, D.; O’Neill, B.; Gibson, K.; Thurston, W. Primary healthcare needs and barriers to care among Calgary’s homeless populations. BioMed Cent. 2015, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Service Australia. Bulk Billing; Australian Government: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett-Daly, G.; Unwin, M.; Dinh, H.; Dowlman, M.; Harkness, L.; Laidlaw, J.; Tori, K. Development and Initial Evaluation of a Nurse-Led Healthcare Clinic for Homeless and At-Risk Populations in Tasmania, Australia: A Collaborative Initiative. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burda, C.; Haack, M.; Duarte, A.C.; Alemi, F. Medication adherence among homeless patients: A pilot study of cell phone effectiveness. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2012, 24, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamathi, A.; Salem, B.E.; Zhang, S.; Farabee, D.; Hall, B.; Khalilifard, F.; Leake, B. Nursing case management, peer coaching, and hepatitis a and B vaccine completion among homeless men recently released on parole: Randomized clinical trial. Nurs. Res. 2015, 64, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jego, M.; Grassineau, D.; Balique, H.; Loundou, A.; Sambuc, R.; Daguzan, A.; Gentile, G.; Gentile, S. Improving access and continuity of care for people experiencing homelessness: How could general practitioners effectively contribute? Results from a mixed study. Br. Med. J. 2016, 6, e013610. [Google Scholar]

- Ranasinghe, P. Helter-Shelter: Security, Legality, and an Ethic of Care in an Emergency Shelter; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C. Homelessness and Housing Advocacy: The Role of Red-Tape Warriors; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hauff, A.; Secor-Turner, M. Homeless health needs: Shelter and health service provider perspective. J. Community Health Nurs. 2014, 31, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, K.; Santa Maria, D.; Narendorf, S.; Markham, C.; Swartz, M.; Batiste, C. Access to healthcare among youth experiencing homelessness: Perspectives from healthcare and social service providers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 115, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikar, J.; Vinall-Collier, K.; Richemond, J.; Talbot, J.; Serban, S.; Douglas, G. Identifying the barriers and facilitators for people experiencing homelessness to achieve good oral health. Community Dent. Health 2018, 36, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Laporte, A.; Vandentorren, S.; Détrez, M.; Douay, C.; Le Strat, Y.; Le Méner, E.; Chauvin, P. Prevalence of mental disorders and addictions among people experiencing homelessness in the greater Paris area, France. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thorndike, A.; Yetman, H.; Thorndike, A.; Jeffrys, M.; Rowe, M. Unmet health needs and barriers to health care among people experiencing homelessness in San Francisco’s Mission District: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health. Modified Monash Model; Australian Government, Department of Health: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- AHURI. Understanding Changes in Australian Homelessness; Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.; Scutella, R.; Tseng, Y.; Wood, G. How do housing and labour markets affect individual homelessness? Hous. Stud. 2019, 34, 1089–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufferey, C.; Chung, D. ‘Red dust homelessness’: Housing, home and homelessness in remote Australia. J. Rural. Stud. 2015, 41, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufferey, C.; Parkes, A. Family homelessness in regional and urban contexts: Service provider perspectives. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 70, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, D. The rural gap: The need for exploration and intervention. J. Sch. Couns. 2018, 16, n21. [Google Scholar]

- RHIhub. People Experiencing Homelessness; Rural Health Information Hub: Grand Forks, ND, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Homelessness Australia. Homelessness Statistics; Homelessness Australia: Holt, ACT, Australia.

- ABS. Census of Population and Housing: Estimating Homelessness; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ABS. Chronic Conditions; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- City of Launceston. City of Launceston: Transport Strategy; City of Launceston: Hobart, TAS, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- AIHW. Housing Affordability; Australian Institute for Health and Welfare: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- TasCOSS. What Does Poverty Look Like in Tasmania? Tasmanian Council of Social Services: Hobart, TAS, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Homelessness Australia. Homelessness in Tasmania; Homelessness Australia: Holt, ACT, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Habitat. Homelessness and the SDG’s; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.; McCabe, C.; Keogh, B.; Brady, A.; McCann, M. An overview of the qualitative descriptive design within nursing research. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Sefcik, J.; Bradway, C. Characteristics of Qualitative Descriptice Stduies: A Systemanis Review. Res. Nurs. Health 2019, 40, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Galletta, A. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.; Horwitz, S.; Green, C.; Wisdom, J.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. PubMed Cent. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, P.; Stewart, K.; Treasure, E.; Chadwick, B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 204, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, L. 100 Questions (and Answers) About Qualitative Research; Sage: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Springer Open Choice 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2016, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M.; Delahunt, B. Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Irel. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 2017, 8, 3351–33514. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, C.; Phillips, K. Hearing the silent voices: Narratives of health care and homelessness. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 34, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelvakumar, G.; Ford, N.; Kapa, H.; Lange, H.; McRee, A.; Bonny, A. Healthcare Barriers and Utilization Among Adolescents and Young Adults Accessing Services for Homeless and Runaway Youth. J. Community Health 2017, 42, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, M.; Dalton, L.; Maxwell, H.; Cleary, M. A qualitative exploration of women’s resilience in the face of homelessness. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 1212–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, B.; Metraux, S.; Sbrocco, T. Health service access among homeless veterans: Health access challenges faced by homeless African American veternas. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, A.; Nyamathi, A.; Getzoff, D. Health-seeking challenges among homeless youth. Nurs. Res. 2010, 59, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wille, S.; Kemp, K.; Greenfield, B.; Walls, M. Barriers to healthcare for American Indians experiencing homelessness. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 2017, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- RACGP. Chapter 3: Funding Australian General Practice Care. 3.2: General Practice Billing; Royal Australian College of General Practitioners: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- AMA. General Practice Facts; Australian Medical Association: St Leonards, NSW, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vuillermoz, C.; Vandentorren, S.; Brondeel, R.; Chauvin, P. Unmet healthcare needs in homeless women with children in the Greater Paris area in France. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIHW. Launceston General Hospital; Australian Institute for Health and Welfare: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ABS. 1307.6—Tasmanian State and Regional Indicators, Jun 2008; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- AIHW. Health Literacy; Australian Institute for Health and Welfare: Canberra, NSW, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, N.; Sheridan, S.; Donahue, K.; Halpern, D.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACSQHC. National Statement on Health Literacy; Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Elmer, S.; Bridgman, H.; Williams, A.; Bird, M.; Jones, R.; Cheney, M. Evaluations of health literacy program for chronic conditions. Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2017, 1, e100–e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, L. Health Literacy: Improving Health, Health Systems, and Health Policy Around the World: Workshop Summary; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Strange, C.; Fisher, C.; Arnold-Reed, D.; Brett, T.; Chan, W.; Ping-Delfos, S. A general practice street health service: Patient and allied service provider perspectives. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 47, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Questions |

|---|

| General |

| 1. What is your position within the agency? What does your role involve? Which programs are you responsible for? How long have you been in the role? |

| 2. Can you tell me a little bit about the services that your organisation provides? |

| Service provision |

| 1. What in your experience are the main health issues that people experiencing homelessness need services for? |

| 2. Where are people experiencing homelessness currently seeking health support from? |

| 3. How do health and community services address the needs of the homeless? What needs go unmet? |

| 4. What do you think are the barriers and challenges for people experiencing homelessness in accessing healthcare? |

| 5. What barriers do you face in providing services/care for the homeless population? |

| 6. What factors do you think assist the homeless in accessing healthcare? |

| 7. Are there any particular services that you believe need to be provided/improved? How can services be better provided? |

| 8. Does your organisation refer clients onto healthcare services? If so, how does this work and to which organisations? How successful is this referral process? |

| 9. Is there anything else you would like to add? |

| Participant Number | Agency Type | Role of Agency | Position in Agency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Community agency | Housing support (crisis accommodation) | Client support worker |

| 2 | Hospital | Provision of healthcare | Social worker |

| 3 | Hospital | Provision of healthcare | Social worker |

| 4 | Community agency | Provision of healthcare | Nurse Practitioner |

| 5 | Community agency | Community Centre | General manager |

| 6 | Community agency | Emergency relief | Case Manager |

| 7 | Community agency | Housing support (long-term accommodation) | General manager |

| 8 | Community agency | Emergency relief | Case worker |

| 9 | Community agency | Housing support (crisis accommodation) | Client support worker |

| 10 | Community agency | Housing support (crisis accommodation) | Client support worker |

| 11 | Community agency | Housing support (crisis accommodation) | Client support worker |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bennett-Daly, G.; Maxwell, H.; Bridgman, H. The Health Needs of Regionally Based Individuals Who Experience Homelessness: Perspectives of Service Providers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8368. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148368

Bennett-Daly G, Maxwell H, Bridgman H. The Health Needs of Regionally Based Individuals Who Experience Homelessness: Perspectives of Service Providers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(14):8368. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148368

Chicago/Turabian StyleBennett-Daly, Grace, Hazel Maxwell, and Heather Bridgman. 2022. "The Health Needs of Regionally Based Individuals Who Experience Homelessness: Perspectives of Service Providers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 14: 8368. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148368

APA StyleBennett-Daly, G., Maxwell, H., & Bridgman, H. (2022). The Health Needs of Regionally Based Individuals Who Experience Homelessness: Perspectives of Service Providers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8368. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148368