Risky Play and Social Behaviors among Japanese Preschoolers: Direct Observation Method

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Participants

2.3. Study Design

- Social behaviorsThe 25-item parental rating form of the SDQ (Japanese version) was used as the objective variable for prosocial behavior and difficulties in daily life [25]. SDQ had been shown to be a valid and reliable questionnaire [23], and the Japanese version of SDQ was also confirmed to be valid and reliable among Japanese children [25]. The SDQ consists of five subscales: “prosocial behavior”, “hyperactivity/inattention”, “problem behavior”, “emotional instability”, and “friendship problems”. Parents were asked to answer each item using a three-point scale from “not applicable (0 point)” to “applicable (2 points)”. In this study, the “total difficulty score”, which is the sum of the “prosocial behavior score” and the four subscales excluding it, was used. The higher the prosocial behavior score, the more prosocial the behavior. In contrast, the range of the overall difficulty score is 0–40, with higher scores indicating more difficult behaviors. Previous studies have confirmed good internal consistency of the overall difficulty scores (Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.78 [26]).

- Risky playThe data were collected by four trained observers following a strict protocol using the nature observation method [27]. Before the data collection, the observers had standardized sessions to make sure their evaluation was consistent among the observers. More specifically, the observers were asked to evaluate the randomly collected children’s play. When the observers’ evaluations differed, the observers discussed and reached a consensus to ensure consistency among the observers.The risky play observations were conducted during free play time (12:30–13:30) from 25–27 October 2021 (3 days). In this study, a time sampling method [28] of 30 s/time per children was used. Measurements were taken by observing the activities during free play in each of the four play areas (open space, playground space, sand space, and indoor space) (Figure 1). At first, the observers were asked to record children’s free play every 30 s. Thereafter, children’s play were categorized “risky play” or “non-risky play” using the Risky Play Scale [24] which was validated by previous studies [13,29,30,31]. In the Risky Play Scale, there were six subcategories (i.e., great heights, high speed, dangerous tools, dangerous elements, disappear/get lost, and rough and tumble play) and children’s behavior were also categorized using the subscale.

- CovariatesPrevious studies have reported that physical activity and parental factors influence young children’s risky play and social skills [32,33,34,35]. In this study, we collected data on physical activity and the parental employment status. Physical activity was measured by a triaxial accelerometer (ActiGraph wGT3X-BT, LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA). Accelerometers are proven to be valid and reliable activity monitors for measuring physical activity in children [36,37]. Participants were asked to wear the accelerometer on the right side of their waist using a belt, for seven consecutive days (Monday through Sunday), except during sleep or water-based activities (e.g., showering or swimming). Data were collected in 15-s epochs. Non-wear time was defined as a period of more than 60 min of continuous zero counts recorded in ActiGraph [38]. Only participants with at least 10 h of wear per day and a minimum of 4 days (including at least one weekend) were included in the analysis [39]. For each participant, the mean MVPA (min/day) was calculated. The cutoff points from Evenson et al. (2008) [36] were selected to determine the time spent on MVPA. MVPA time was calculated as mean daily minutes ≥ 2296 counts/min from all valid days. Data collected were stored in ActiLife software version 6.13.3 (ActiGraph, LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA). Parental employment status was asked of the parents by means of a questionnaire. These were defined as “Single-income family” when one of the parents worked, and “Dual-income family” when both parents or one parent in a single-parent household worked. Full-time and part-time workers were not considered.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Risky Play

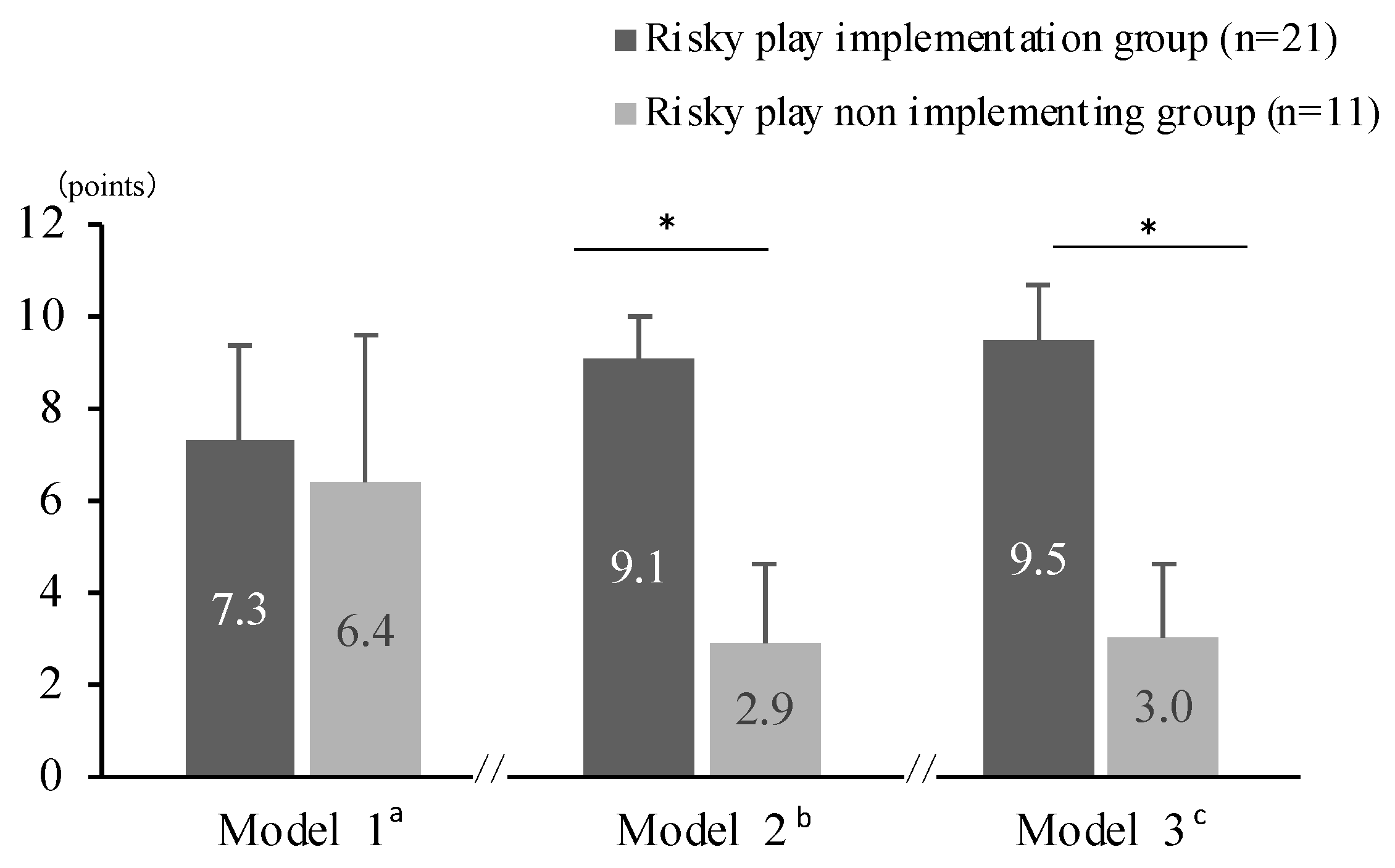

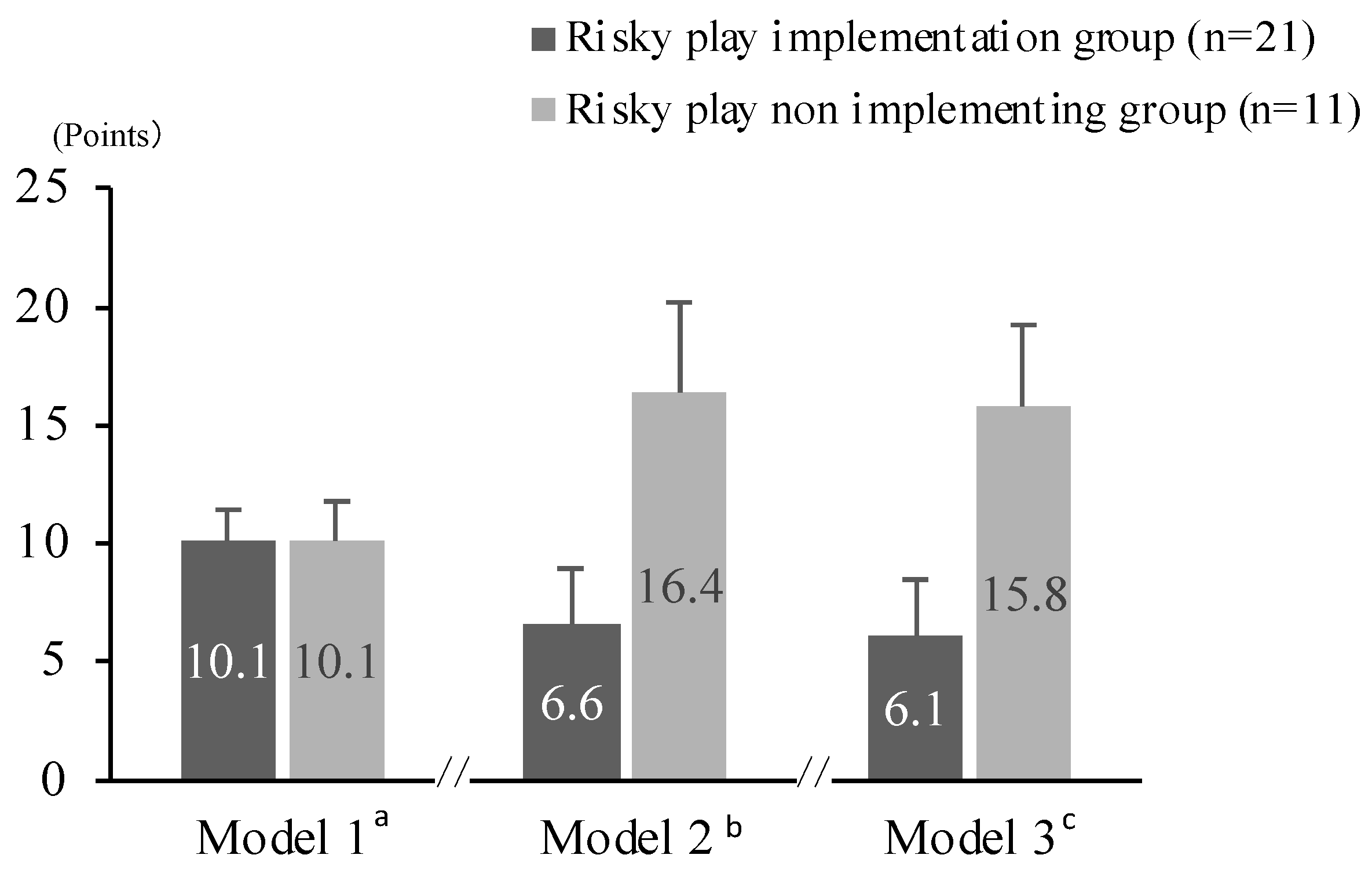

3.2. Relationship between Risky Play and Social Behaviors

4. Discussion

4.1. Facts about Risky Play

4.2. Relationship between Risky Play and Social Behaviors

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tillmann, S.; Tobin, D.; Avison, W.; Gilliland, J. Mental health benefits of interactions with nature in children and teenagers: A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCurdy, L.E.; Winterbottom, K.E.; Mehta, S.S.; Roberts, J.R. Using nature and outdoor activity to improve children’s health. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2010, 40, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, R. Does access to green space impact the mental well-being of children: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2017, 37, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, A.; Hughes, A.R.; Martin, A.; Reilly, J.J. Utilising active play interventions to promote physical activity and improve fundamental movement skills in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulain, T.; Sobek, C.; Ludwig, J.; Igel, U.; Grande, G.; Ott, V.; Kiess, W.; Körner, A.; Vogel, M. Associations of Green Spaces and Streets in the Living Environment with Outdoor Activity, Media Use, Overweight/Obesity and Emotional Wellbeing in Children and Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Cadenas-Sánchez, C.; Estévez-López, F.; Muñoz, N.E.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Migueles, J.H.; Molina-García, P.; Henriksson, H.; Mena-Molina, A.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. Role of physical activity and sedentary behavior in the mental health of preschoolers, children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 1383–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loukatari, P.; Matsouka, O.; Papadimitriou, K.; Nani, S.; Grammatikopoulos, V. The Effect of a Structured Playfulness Program on Social Skills in Kindergarten Children. Int. J. Instr. 2019, 12, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.; Lee, E.-Y.; Hesketh, K.D.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Predy, M.; Rhodes, R.E.; Rinaldi, C.M.; Spence, J.C.; Hinkley, T. Physical activity and sedentary behavior across three time-points and associations with social skills in early childhood. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mullan, K. A child’s day: Trends in time use in the UK from 1975 to 2015. Br. J. Sociol. 2019, 70, 997–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benesse Educational Research and Development Institute, Fifth Infant Life Survey Report. Available online: https://berd.benesse.jp/up_images/research/YOJI_all_P01_65.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Kennair, L.E.O. Children’s risky play from an evolutionary perspective: The anti-phobic effects of thrilling experiences. Evol. Psychol. 2011, 9, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Kleppe, R. Outdoor Risky Play. In Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development; Tremblay, R.E., Boivin, M., Peters, R.D., Brussoni, M., Eds.; Encylopedia on Early Childhood Development: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2019; Available online: http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/outdoor-play/according-experts/outdoor-risky-play (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Kleppe, R.; Melhuish, E.; Sandseter, E.B.H. Identifying and characterizing risky play in the age one-to-three years. Eur. Early Child Educ. Res. J. 2017, 25, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.D. Elementary-school children’s rough-and-tumble play and social competence. Dev. Psychol. 1988, 24, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWolf, D.M. Preschool Children’s Negotiation of Intersubjectivity during Rough-and-Tumble Play; Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, M.J.; Lindsey, E.W. Preschool children’s pretend and physical play and sex of play partner: Connections to peer competence. Sex Roles 2005, 52, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, H.F.; Lester, K.J. Adventurous play as a mechanism for reducing risk for childhood anxiety: A conceptual model. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 24, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, M.; Steinberg, L. Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: An experimental study. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 41, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sirard, J.R.; Pate, R.R. Physical activity assessment in children and adolescents. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parten, M.B. Social participation among pre-school children. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1932, 27, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arney, F.M. A Comparison of Direct Observation and Self-Report Measures of Parenting Behaviour. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Adelade, Adelade, Australia, 2004. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2440/37713 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Pellegrini, A. The role of direct observation in the assessment of young children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2001, 42, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Lamping, D.L.; Ploubidis, G.B. When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): Data from British parents, teachers and children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Sando, O.J.; Kleppe, R. Associations between children’s risky play and ECEC outdoor play spaces and materials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, Y.; Moriwaki, A.; Komatsu, S.; Kamio, Y. Standardization of Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire based on parents’ and teachers’ ratings among preschool children (4-5 years old) in Japan. In Prevalence and Developmental Changes of Developmental Disorders in Pre- and Post-School Children: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Study; Kamio, Y., Ed.; National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; pp. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Theunissen, M.H.; Vogels, A.G.; de Wolff, M.S.; Reijneveld, S.A. Characteristics of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in preschool children. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e446–e454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, P.K. Observational Methods in Studying Play; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Altmann, J. Observational study of behavior: Sampling methods. Behaviour 1974, 49, 227–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hansen Sandseter, E.B. Categorising risky play—How can we identify risk-taking in children’s play? Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 15, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Characteristics of risky play. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2009, 9, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen Sandseter, E.B.; Kleppe, R.; Sando, O.J. The Prevalence of Risky Play in Young Children’s Indoor and Outdoor Free Play. Early Child. Educ. J. 2020, 49, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, M.J.; Wendel-Vos, W.; van Oers, H.A.; Van de Goor, I.A.; Schuit, A.J. Environmental determinants of outdoor play in children: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boxberger, K.; Reimers, A.K. Parental correlates of outdoor play in boys and girls aged 0 to 12—A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guryan, J.; Hurst, E.; Kearney, M. Parental education and parental time with children. J. Econ. Perspect. 2008, 22, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noi, S.; Shikano, A.; Tanaka, R.; Tanabe, K.; Enomoto, N.; Kidokoro, T.; Yamada, N.; Yoshinaga, M. The pathways linking to sleep habits among children and adolescents: A complete survey at Setagaya-ku, Tokyo. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R.; Catellier, D.J.; Gill, K.; Ondrak, K.S.; McMurray, R.G. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedson, P.; Pober, D.; Janz, K.F. Calibration of accelerometer output for children. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, S523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masse, L.C.; Fuemmeler, B.F.; Anderson, C.B.; Matthews, C.E.; Trost, S.G.; Catellier, D.J.; Treuth, M. Accelerometer data reduction: A comparison of four reduction algorithms on select outcome variables. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005, 37, S544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trost, S.G.; Pate, R.R.; Freedson, P.S.; Sallis, J.F.; Taylor, W.C. Using objective physical activity measures with youth: How many days of monitoring are needed? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watchman, T.; Spencer-Cavaliere, N. Times have changed: Parent perspectives on children’s free play and sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2017, 32, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, H.; Sandseter, E.B.H.; Wyver, S. Early childhood teachers’ beliefs about children’s risky play in Australia and Norway. Contemp. Issues Early Child 2012, 13, 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Gibbons, R.; Gray, C.; Ishikawa, T.; Sandseter, E.B.; Bienenstock, A.; Chabot, G.; Fuselli, P.; Herrington, S.; Janssen, I.; et al. What is the relationship between risky outdoor play and health in children? A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6423–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezza, M.; Pilloni, S.; Morabito, C.; Sersante, C.; Alparone, F.R.; Giuliani, M.V. The influence of psychosocial and environmental factors on children’s independent mobility and relationship to peer frequentation. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 11, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, C.; Goldenstein, S.L.; Rosengarten, T. Benefits and Risks of Tree Climbing on Child Development and Resiliency. Early Child. Educ. J. 2018, 5, 10–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, A.D. Elementary school children’s rough-and-tumble play. Early Child. Res. Q. 1989, 4, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, H.; Eager, D. Risk, challenge and safety: Implications for play quality and playground design. Eur. Early Child Educ. Res. J. 2010, 18, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrongiello, B.A.; Kane, A.; Zdzieborski, D. “I think he is in his room playing a video game”: Parental supervision of young elementary-school children at home. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011, 36, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, E.Y.; Bains, A.; Hunter, S.; Ament, A.; Brazo-Sayavera, J.; Carson, V.; Hakimi, S.; Huang, W.Y.; Janssen, I.; Lee, M. Systematic review of the correlates of outdoor play and time among children aged 3-12 years. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brussoni, M.; Olsen, L.L.; Pike, I.; Sleet, D.A. Risky play and children’s safety: Balancing priorities for optimal child development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3134–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelleyman, C.; McPhee, J.; Brussoni, M.; Bundy, A.; Duncan, S. A cross-sectional description of parental perceptions and practices related to risky play and independent mobility in children: The New Zealand state of play survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McFarland, L.; Laird, S.G. Parents’ and early childhood educators’ attitudes and practices in relation to children’s outdoor risky play. Early Child Educ. J. 2018, 46, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Borghese, M.M.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.P.; Janssen, I.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Pate, R.R.; Connor Gorber, S.; Kho, M.E. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S197–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocki, K.C.; Bohlin, G. Executive functions in children aged 6 to 13: A dimensional and developmental study. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2004, 26, 571–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | Schedule |

|---|---|

| ~9:00 | Going to kindergarten |

| ~10:45 | Free play time |

| ~11:40 | All together childcare |

| 12:00~12:30 | Lunch |

| ~13:30 | Free play time |

| 14:00~ | Going home from kindergarten |

| All (n = 32) | Boys (n = 21) | Girl (n = 11) | Comparisons, p-Value (Boys vs. Girls) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic characteristics | ||||

| Age (month) | 71.4 ± 3.5 | 71.3 ± 3.7 | 71.6 ± 3.2 | p = 0.208 |

| Risky play | ||||

| Risky play implementation rate (%) | 12.1 | 14.2 | 9.8 | p < 0.001 * |

| Great heights (%) | 2.1 | 2.8 | 1.6 | |

| High speed (%) | 8.6 | 9.6 | 7.1 | |

| Dangerous tools (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Dangerous elements (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Disappear/get lost (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rough and Tumble play (%) | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.1 | |

| Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire | ||||

| Prosociality scores (points) | 6.9 ± 2.6 | 7.0 ± 2.5 | 6.9 ± 2.8 | p = 0.959 |

| Total difficulty score (points) | 10.1 ± 5.7 | 10.5 ± 5.0 | 9.1 ± 7.0 | p = 0.522 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Imai, N.; Shikano, A.; Kidokoro, T.; Noi, S. Risky Play and Social Behaviors among Japanese Preschoolers: Direct Observation Method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137889

Imai N, Shikano A, Kidokoro T, Noi S. Risky Play and Social Behaviors among Japanese Preschoolers: Direct Observation Method. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(13):7889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137889

Chicago/Turabian StyleImai, Natsuko, Akiko Shikano, Tetsuhiro Kidokoro, and Shingo Noi. 2022. "Risky Play and Social Behaviors among Japanese Preschoolers: Direct Observation Method" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 13: 7889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137889

APA StyleImai, N., Shikano, A., Kidokoro, T., & Noi, S. (2022). Risky Play and Social Behaviors among Japanese Preschoolers: Direct Observation Method. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 7889. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137889