Abstract

School nutrition programs mitigate food insecurity and promote healthy eating by offering consistent, nutritious meals to school-aged children in communities across the United States; however, stringent policy guidelines and contextual challenges often limit participation. During COVID-19 school closures, most school nutrition programs remained operational, adapting quickly and innovating to maximize reach. This study describes semi-structured interviews with 23 nutrition directors in North Carolina, which aimed to identify multi-level contextual factors that influenced implementation, as well as ways in which the innovations during COVID-19 could translate to permanent policy and practice change and improve program reach. Interviews were conducted during initial school closures (May–August 2020) and were deductively analyzed using the Social Ecological Model (SEM) and Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Analysis elicited multiple relevant contextual factors: director characteristics (motivation, leadership style, experience), key implementation stakeholders (internal staff and external partners), inner setting (implementation climate, local leadership engagement, available resources, structural characteristics), and outer setting (state leadership engagement, external policies and incentives). Findings confirm the strength and resilience of program directors and staff, the importance of developing strategies to strengthen external partnerships and emergency preparedness, and strong support from directors for policies offering free meals to all children.

1. Introduction

The National School Lunch Program was established in 1946 to achieve two primary goals: (1) to “safeguard the health and well-being of the Nation’s children” and (2) to “encourage the domestic consumption of nutritious agricultural commodities and other food” [1]. The National School Breakfast Program, Summer Food Service Program, and other federal programs were later added to expand nutritious food access for children year-round. This suite of School Nutrition Programs is administered by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and around 30 million children participate annually [2]. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the critical contributions of these programs and potential for innovative change.

School nutrition programs are one of the largest food assistance programs in the United States, but they are not without controversy. School meals are primarily funded through federal reimbursements to school food authorities (SFAs; often school districts) for each meal served. The reimbursement rate is based on student financial eligibility, with some students qualifying for free, some reduced-price, and some full-priced meals [3]. Advocacy around making school meals free for all students (also referred to as “healthy school meals for all”) has grown in recent years. Supporters of healthy school meals for all often cite evidence that school nutrition programs promote better educational outcomes among students of all socioeconomic backgrounds [4], the potential to reduce stigma related to participating in school meals and “lunch shaming” stemming from unpaid meal balances [4,5,6], and the financial stability of maximizing student participation [6]. Concerns about federal policies enabling free school meals for all students have typically centered around the cost to federal and/or state governments and the necessity or appropriateness for students whose families can afford to pay [7,8,9].

The COVID-19 pandemic illustrated the potential for federal policy and local school systems to innovate quickly. The positioning of school meal programs and staff as “essential” became widely accepted during the early months of the pandemic, and policy makers prioritized free and accessible meals for as many families as possible [10]. In March 2020, most governors issued an executive order directing all public schools to close in an effort to limit the spread of COVID-19 [11]. During the emergency school closures, USDA issued a series of waivers that permitted programs to serve meals through the National School Lunch Program—Seamless Summer Option or Summer Food Service Program. This allowed program operators to receive higher reimbursement rates per meal [12]. USDA issued additional waivers allowing administrative flexibility in meal pattern and meal service requirements (e.g., enabling parent pickup, grab-n-go, and delivery options) to facilitate program continuation while mitigating virus spread [13]). Although this was not the first time the USDA granted flexibility in school meal program administration (e.g., during natural disasters), the COVID-19 pandemic was unique in its prolonged, pervasive, and highly visible shock to several interconnected systems that impact school meal programs.

School nutrition directors (SNDs) are trained professionals responsible for administering school nutrition programs at the local SFA level. During COVID-19, SNDs were forced to adapt quickly and continuously to an emerging disaster that exacerbated food insecurity, disrupted supply chains, and presented new and uncertain risks to employees [14]. COVID-19 brought new public attention to the role of school nutrition programs in safeguarding the health and wellbeing of the nation’s children and serving as hubs of resilience in communities [15,16,17]. There is a burgeoning body of qualitative and mixed methods literature describing the critical role of school meal distribution programs in improving food access across the country during COVID-19, the challenges faced and solutions implemented, and the innovative strategies used to ensure that children and families were fed [18,19,20,21,22,23]. In this study, we seek a deeper understanding of the contextual factors that influenced these challenges, solutions, and innovations across multiple levels.

This study describes findings from semi-structured interviews with SNDs across North Carolina during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic. We use the Social Ecological Model (SEM) and Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to describe multi-level contextual factors that influenced program operations, with the goal of identifying factors to address and/or leverage post-pandemic to enable school meal programs to realize their full potential as hubs of resilience in community food systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. North Carolina Context

In North Carolina (NC) during the 2019–2020 school year, prior to schools closing due to COVID-19, 204 SFAs, including public school districts, charter schools, and residential child care institutions, operated federally assisted school nutrition programs [24]. In fiscal year 2019, the average daily participation in the National School Lunch Program in NC was 835,081 students, [2] approximately 49% of all school-aged children in NC [25]). Of these, 58% received meals for free or at a reduced price [26]. An additional 455,308 breakfasts were served daily [27].

The governor of NC issued an executive order directing all public schools to close for two weeks beginning Monday, 16 March 2020 in an effort to limit the spread of COVID-19 [28]. The NC Department of Public Instruction, the NC Department of Health and Human Services, and the NC State Board of Education were tasked with developing a plan to provide for the health, nutrition, and safety of children while schools were closed. In the first week, more than 1.2 million school meals were served across the state [29]. When school closures were extended, many SFAs usedfederal waivers to continue meal service.

2.2. Recruitment

We used several recruitment tactics to recruit school nutrition directors (SNDs) to participate in interviews. First, an email invitation was distributed by a member of the research team via state-wide listserv to SNDs in all public school districts. Second, we sent targeted emails to SNDs in a subset of districts (n = 30) selected to maximize demographic diversity and capture regional perspectives. Third, a representative from the state education agency sent a second email invitation via state-wide listserv. The state agency representative also announced the study at a statewide meeting with SNDs in May 2020. A total of 31 SNDs were recruited through these methods; of these, 23 (74%) completed interviews. Interviewees were mailed high-quality aprons for their participation. Study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the Duke University Health System.

2.3. Data Collection

Interviews were conducted by five trained interviewers and recorded via a video conferencing platform between 27 May and 12 August 2020, a period over which USDA’s waivers were issued and re-issued at various time points with uncertain expiration dates [29]. The interview guide was developed iteratively by the research team with input from state and local school nutrition stakeholders. The guide drew from a question bank repository developed by a national working group [30]. We modified the questions from the repository to ensure both local and national relevance and to align with study objectives. The final interview guide is included in Supplemental File S1. At the end of summer 2020 (about 6 months from the start of the pandemic), we determined that we had adequate information power (e.g., sample specificity, based on established theory, narrow study aim, strong dialogue quality, limited comparison in analytic strategy) and thus, further recruitment was not necessary [31].

2.4. Data Analysis

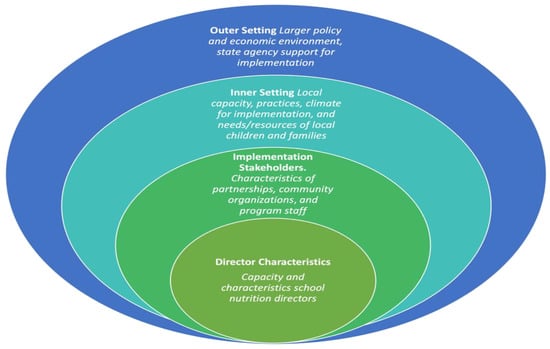

Recordings were transcribed verbatim and de-identified. De-identified transcripts were coded and analyzed using Dedoose (Version 9.0.46, Los Angeles, CA, USA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, 2022). Data analysis was driven by a hybrid deductive/inductive phenomenological approach. We iteratively developed a codebook that combined the SEM and the CFIR. SEM was first conceptualized by Bronfenbrenner in 1979 to describe the multi-level systems of influence on individual behavior change and is frequently employed to guide public health prevention efforts [32]. The CFIR complements the SEM by providing a menu of constructs that describe factors that influence implementation of evidence-based public health efforts across the multiple levels of the SEM [33]. Our overarching framework is illustrated by Figure 1. The framework defines multiple levels through integrating SEM and CFIR terminology, and subcodes defined across each level largely reflect CFIR constructs of most relevance to our study. Transcripts were first divided into excerpts using three time-based codes: Pre COVID-19, During COVID-19, and Beyond COVID-19. Those excerpts were subsequently content-coded using a combination of descriptive and process hierarchical coding across four levels, whereby codes and subcodes were informed by the SEM and the CFIR [34]. All data were double-coded, with a total of five coders meeting in teams of two (one coder left the study team and was replaced by another) to reach consensus. Coders then used matrices for each code to identify potential themes, which were discussed and agreed upon by the full coding team. Pre-COVID and during-COVID codes were condensed to describe factors across multiple levels that influenced the implementation of school meal programs during the pandemic, and the beyond-COVID codes described how those factors may continue to influence implementation beyond the pandemic. Coding methods for all time-based code categories were systematically tracked using meeting minutes, memos, and a detailed audit trail [34,35].

Figure 1.

Social Ecological Model (SEM) and Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)-based coding framework of multi-level implementation factors influencing school meal program operations during COVID-19.

3. Results

As described in Table 1, of the 23 SNDs recruited for the study, 21 (91%) represented SFAs that were public school districts and two (9%) represented public charter school systems. SNDs represented SFAs from all eight of the state’s service regions. Based on the National Center for Education Statistics [36], districts were 74% rural, 9% urban, and 17% suburban/town, which is representative of the state as a whole [37]. Interviews averaged 47 min in length (range: 32–84 min).

Table 1.

Characteristics of districts and charters represented by participating school nutrition directors (n = 23).

Below, we present themes elicited from subcodes within each level of our framework in two sections: Implementation Factors Influencing Program Operations During COVID-19, and Beyond COVID-19: Influences on Future Operations. Code definitions and themes are described in more detail in Table 2.

Table 2.

Themes and representative quotes related to implementation factors influencing school meal program operations during the early months of COVID-19, including future anticipated influences.

3.1. Implementation Factors Influencing Program Operations during COVID-19

“It may have not have been the prettiest, but we damn sure did it”. (North Central, Rural)

Although the logistical details of program operations (e.g., how food was procured, prepared, and distributed) varied across our sample, all SNDs described using the waivers to begin serving meals almost immediately after schools closed. Most continued to serve meals in some capacity through the end of the 2019–2020 school year and into summer 2020. Directors described fears of COVID-19 spread, staff safety concerns and labor shortages, food and packaging shortages, and uncertainty around federal policies and reimbursement structures. Key themes related to factors that influenced program implementation are summarized below by SEM/CFIR-based parent codes, and illustrated with additional quotes in Table 2.

“It wasn’t even a question in our minds. We were going to do something, whether we’ve got funding or whether we didn’t, whatever happened”. (Western, Rural)

3.1.1. Director Characteristics

We identified several characteristics of the SNDs themselves that influenced program operations: motivation/values, leadership style, and experience. SNDs described being willing to go above and beyond to operate their programs. They worked long hours and played many roles to ensure their programs met their ultimate goal of feeding kids.

“We could serve masses and masses of people from our serve line. That’s what we do all day long”. We’re experts at that. But when you threw in the, “Oh, by the way, you’re going to take everything on a bus”. We were like, “Okay. Yeah, we could do this. Because we’re—I call ourselves ‘the bendy flexibles’”. (Northeast, Rural)

Motivation and Values

We identified several motivations for SNDS to continue operations during early pandemic days, including their connection with the students and a sense of purpose behind what they do for a living. They were motivated by the knowledge they were feeding children who needed the food to survive and thrive.

“When people ask me what I do for a living, I said, ‘I feed hungry children. I do that with a smile and a hell of a lot of pride’”. (Southeast, Rural)

SNDs were also motivated to be good stewards of funding and resources (e.g., by using commodities and items they already had on hand), and keep grab-n-go food appealing to students despite it being pre-packaged. A sense of responsibility for the safety and morale of their staff was commonly mentioned. Directors described specific new approaches to supporting their team members, such as offering new employee incentives (e.g., childcare).

Leadership Style

Whereas SNDs were not always involved in decision making at the district level, many did report increased communication with local leaders by necessity. Several SNDs noted that being involved in decision making allowed them to act proactively and plan before the school closures in order to begin meal service immediately. In addition, many directors described the necessity of using a team-based approach. They gathered input from staff and modified operations based on staff recommendations. They also realized the need to publicly recognize the hard work of their staff.

“I wrote a grant for two purposes, employee incentives and for supplies. So…after our supplies were purchased, I divided up [the remaining funds] by the number of employees, and at my end of the year recognition banquet, I offered them that remaining sum per employee”. (Southeast, Suburban/Town)

Experience

Although most SNDs acknowledged it was difficult to be prepared for the massive changes required for pandemic operations, many described drawing on past experiences (e.g., hurricane-induced school closures) to increase their confidence and guide decision making. Their familiarity with various areas of program management and general need to be thrifty and flexible during financial challenges prepared them to lead during the pandemic.

“The thing with school nutrition is that we roll with the punches. If you tell us one day that we’ve got to do something different, we’re going to say, ‘Okay, let me figure it out. We got it. Let’s just roll on with it’”. (North Central, Rural)

3.1.2. Implementation Stakeholders

Both internal staff (e.g., food service staff, administrators, teachers, maintenance, and transportation staff) and external partners (e.g., community organizations and individual volunteers) played a critical role in pandemic operations.

Internal Staff

Overall, SNDs described staff as “unsung heroes” who were dedicated, flexible, creative, and willing to take on new roles in order to prepare and distribute food.

“Those employees have become delivery drivers. Those employees have become whatever you wanted them to be. No one has really complained because we’re all in it for the same purpose, and that is to make sure those kids are being fed. I mean, I have my Spanish interpreter that learned how to drive a big box truck”. (Piedmont-Triad, Rural)

Many SNDs described staffing challenges due to COVID-19 fears, resentment among working staff toward staff who were being paid while staying home [38], or feeling under-appreciated by community members. Many SNDs worked with districts to fill these gaps (and provide employment opportunities) to non-food-service district employees (e.g., transportation, maintenance, teachers, administrators) who distributed and delivered food. Working with these employees not only helped to mitigate staff shortages, but also improved relationships and communication across departments that had not worked together previously.

“A lot of times my staff feels like they’re not part of the school, and I think this has really changed that. We’ve had the collaboration of teachers’ assistants, custodians, principals, school resource officers. Principals were helping load buses in the morning with coolers and helping lift things. All different groups that pitched in and helped out because they wanted to make sure the kids got fed. It was a great experience”. (Western, Suburban/Town)

External Partners

Many directors reported strengthening and/or forming new partnerships during the pandemic, including with the county health department, community organizations (e.g., churches), national organizations (e.g., No Kid Hungry), other school districts, and local food suppliers (e.g., restaurants). These organizations often provided “no strings attached” support via grants, packaging and food supplies, volunteers, or funds, which was generally welcomed if they met specific pandemic-related needs.

“Within 24-h, I had 14 churches show up with all of the supplies that they had had in their fellowship halls…hinge containers, and bags, and full sheets. I just made them a list of ‘this is what I need.’ And [they] went out and recruited it from restaurants. Got it from Sam’s. They made trips and sales to try to fill our need, and they did”. (Piedmont-Triad, Rural)

A few SNDs diverged from this theme, noting that this type of support may have been random and sporadic, and thus was not a reliable method for keeping programs operating or meeting the needs of hungry students in their community.

3.1.3. Inner Setting

The Inner Setting describes factors associated with the success of programs during school closures in the school, school district, and local community. Named factors included implementation climate within the community, local leadership engagement, available resources, and structural characteristics.

Implementation Climate

Even though a few SNDs experienced pushback from program participants or community members that hindered program operations or impacted staff morale, most described an increased appreciation of and support for school meal programs among caregivers, students, and the community. This acknowledgement and recognition increased morale and facilitated smoother operations because people wanted to help and were sympathetic through difficult changes. Importantly, the positive attention was felt in contrast to the limited and sometimes negative attention SNDs felt their programs received prior to the pandemic.

“…I feel appreciated. When they came in and said feeding the kids is the No. 1 priority, [we] really felt appreciated. We don’t always feel like we’re a priority. We always feel at the other end of the scale. But people have come to realize that we are important”. (Northeast, Rural)

“We’ve gotten lots of thank-you’s, thank-you’s, thank-you’s. We’ve had parents actually mail thank-you’s straight to our office. We’ve had kids decorate their sidewalks”. (Piedmont-Triad, Rural)

Local Leadership Engagement

In general, SNDs described school and district leaders (e.g., superintendents) as supportive from the start—either through taking swift action and helping to solve problems, or by being open to input from the SNDs and not “obstructing” their efforts.

“My superintendent stepped up and offered [incentive] to transportation and school nutrition employees that were serving and each stop got $50 a day in addition to their salary as a bonus pay”. (Southeast, Suburban/Town)

The urgency of decision making often necessitated more frequent communication between district leadership and SNDs than before the pandemic. Some SNDs noted that district leadership also gave more attention to helping programs communicate with families to keep them aware of site locations, meal pick up or delivery times, menus, and other critical pieces of information.

Available Resources

With the influx of demand for packaging supplies, pre-packaged foods, and personal protective equipment across the country, most SNDs experienced supply shortages and skyrocketing costs. Many used USDA commodities and other food they had stored, and the waivers enabled them to problem-solve and use creative new strategies to procure, prepare, and distribute food. However, operations were hindered by supply chain issues, and SNDs often expressed concern about the amount of money that was being spent without certainty of reimbursement, particularly in districts where programs already faced financial challenges.

“They want us to do all these things, but then they’re like, ‘Well, you have to buy it yourself.’ And I’m like, we’re already losing money. We’re trying not to, but our system has lost money probably for the last five or six years, and we’re trying to reverse it, but it’s a hard trend to reverse, and it’s hard to recoup that money, and so you want me to do this stuff, but I don’t have any funding to do it”. (North Central, Rural)

At the same time, as the above SND acknowledged, increased revenue from the waivers could enable purchase of items that could be used long-term, such as sealing equipment or delivery vehicles.

“Why would we buy $30,000.00 cargo vans when this is a one-time thing? Well, who knows if it’s a one-time thing or not? And if we have the funding now for it, we should go ahead and get them because then we can keep our participation up year-round because we can use those cargo vans for 10 years”. (North Central, Rural)

Structural Characteristics

Various community structural characteristics influenced program operations, such as district size and geography. Several SNDs in smaller districts noted there were both advantages and challenges to being smaller. Having fewer children to feed meant that they could sustain operations with a smaller supply. However, with limited storage capacity and purchasing power, it could be difficult to secure needed food and supplies on short notice, necessitating more creative solutions. One SND described partnering with neighboring districts to meet minimum shipping requirements.

“We’re a small community, we’re about 2100 students, and [nearby County] is also relatively small. When the shortages hit, we were like, let’s call the vendors and see if we can get direct ship straight from the vendor. And a lot of the vendors have minimum shipping amounts. So the problem was, like [nearby County], there’s no way we could handle a minimum 12 cases or 12 pallets of pizza. So I reached out to a director in [nearby county] and said, ‘We may not be able to do it individually, but we could do it together. We could split the inventory.’ So, that’s what we did. We found vendors that had individually wrapped products, like pizzas and sandwiches and all kinds of breakfast items. And we were able to meet the minimum orders”. (North Central, Rural)

Another advantage of smaller districts was more knowledge of the areas in their community where students would be most in need of meals, and as a result of area eligibility waivers, they could place sites in those areas. The waivers also allowed them to use distribution methods that made the most sense for their area—in some cases, delivery via school buses or vans was preferable to distribution at school or community sites due to distance or road quality.

“We’re not doing individual meals delivery. We’re going to where we know the kids are. We’re a rural county, so trailer parks, those kinds of things. And those kids, they’re out there every day, even in the rain. Like today, it was pouring down rain. They’ll still be out there, looking for their meals”. (North Central, Rural)

3.1.4. Outer Setting

Outer Setting factors influence implementation at the outermost level, such as state- and federal-level leadership, statewide networks, and broad policies and practices. We elicited factors across three categories.

State Leadership Engagement

SNDs nearly all agreed that school nutrition leaders in the state’s education department were a “steadying force” that facilitated successful program operations. State leaders took their role as intermediary seriously, bridging the divide between federal waivers that were issued and the directors tasked with implementing waivers on the ground. SNDs praised their constant and efficient communication and appreciated their convening all-director calls that enabled them to ask questions, express concerns, and hear about what other SNDs were doing.

“[State] School Nutrition Program has done a wonderful job of providing us with guidance and assistance as they’ve had it. They’ve [said], ‘We don’t have any answers yet, but this is the guidance we’re giving you.’ They were very good at getting ahold of us any time they actually did decide on something”. (Northwest, Suburban/Town)

External Policies and Incentives—School Nutrition Waivers

All SNDs used the waivers, and most acknowledged that the federal waivers that granted implementation flexibility and higher reimbursement were essential to continuing operations amidst the soaring expenses of labor, goods, and delivery costs and for making sure students in their districts could access meals. As mentioned above, the waivers enabled directors to make decisions that best fit the needs of the families in their communities.

“I am usually a fairly vocal critic of USDA. But they have 100% been outstanding for pulling out all those barriers through this. I recognize why those provisions are put in place during the normal summer meal program to prevent abuse and make sure that kids are the ones that are getting the food. But I’m so glad that they have given us the freedom to give the parent the meal so they don’t feel like they have to bring their babies to a place where the child would be at risk. That they’ve allowed us to set up in areas that ordinarily you wouldn’t even think of putting a meal area and you wouldn’t have participation. But then, you put it in there and you have 80 kids come out. I mean, that just shows me how high the need is across America right now. And so, USDA has absolutely stepped up…” (Southwest, Rural)

However, many directors noted that the ways in which the waivers were handed down (e.g., last-minute changes, shifting expiration dates) resulted in unnecessary contingency planning, costs, emotional distress for directors, and confusion for families. There was constant concern waivers would expire and not be extended, which would cause a scramble for resources and a drop in program participation, leading to a drop in revenue. Many SNDs reported worrying this would lead to staff layoffs, including school bus drivers and other departmental staff who had been working with school nutrition programs to deliver meals, and would reintroduce the known challenges of the program (e.g., stigma) while failing to account for the additional challenges brought on by the pandemic.

“[Expiring waivers are] going to really financially impact your programs, and you’re probably going to put some people out of work, because I really don’t think we can sustain what we’re doing if we drop off our paying kids”. (Piedmont-Triad, Rural)

One SND noted that to prepare for future disasters, the federal government should develop a disaster plan that streamlines the waiver process to ensure smooth program operations.

“As responsive as USDA was, I think it probably would be smart if they had a disaster plan in place already. That would flip the switch and activate six waivers at once instead of having to meet and vote and then get [a new one] every week. That’s the part that’s been a little bit chaotic is every week, something new comes down and you’re like, ‘I hope I got it right.’ But I can tell from the amount of questions on our weekly calls with [the state agency] that there’s still a lot of confusion”. (Southwest, Rural)

External Policies and Incentives—Other Policies

Other federal policies also influenced meal program operations during COVID-19: Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer (P-EBT), a program that provided families the cash equivalent of school meal funding, and funds allocated to school nutrition programs by the state government through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. School food authorities needed to follow specific guidelines in using these funds [39].

When probed about P-EBT, SNDs were generally supportive of the policy but critical of the rollout. SNDs were asked to provide data about free and reduced-price meal program participants for P-EBT eligibility, and many noted that families often asked them about it even though they had very little knowledge about P-EBT because it was managed by a separate state agency. Several SNDs suggested that their programs were more appropriate recipients of federal funding than sending funds directly to families. Additionally, some SNDs perceived or observed a dip in participation in their programs in the days following P-EBT distribution.

“I’m so glad that P-EBT exists… but it has been such a nightmare, logistically. There have been so many mistakes along the way. There’s been people who didn’t receive cards, people who have received cards but it was in a deceased person’s name…And school nutrition has very little that we can do about any of these problems”. (Western, City)

When SNDs discussed CARES Act funding, they had similar sentiments as with the waivers—they appreciated the assistance but either had limited guidance on how to use funds or were hesitant to spend money on items that they were concerned would not be reimbursed as indicated.

3.2. Beyond COVID-19: Influences on Future Operations

Although most SNDs struggled to envision the future of their programs (likely because the interviews occurred during a period of tremendous uncertainty and day-to-day changes), many did suggest that their programs would benefit from continuation of many COVID-era policy changes.

Importantly, many SNDs felt that pandemic operations had demonstrated that a permanent policy change to make meals free for all students could reduce programs’ administrative burden and “microscopic management,” increase their operating budgets, and enable SNDs to focus on meal quality, food, and nutrition education, cultivating a skilled school nutrition workforce, and expanding partnerships in the community. Several directors also noted that the stigma associated with receiving school meals for free or at a reduced price would be resolved if meals were free for everyone.

“I think the federal level just needs to suck it up and say every child gets to eat. The paid kids should not have to hold that program up. It’s not fair to them in my opinion because, if their parents pay or not, it’s not the kid’s fault. So, I think federally the program should just be straight across the board universal. Come up with a plan. You just did it for 12 weeks”. (Northeast, Rural)

“You don’t pay for school. You don’t pay to ride the bus. Why are you paying for meals? I think 110% I would be in favor of [free school meals for all]. I’m not saying it comes without problems. Certainly, it does. …I just don’t see why you should have to pay for school meals. Just fund your districts properly. I’m talking about really from the federal level. And then also from the state level because our state does not really fund [school meals]. We get $0.30 for every reduced child at breakfast, which is great. But a little district, that might be $2000. That’s not a lot of money”. (Southwest, Rural)

In addition to funding districts to provide free meals for all, some SNDs also expressed the need for additional operational funding. While SNDs have had to be thrifty and flexible for years, and these attributes benefited their programs during COVID-19, they also benefitted from the additional funds provided to pay for needed resources, staff, and high-quality food.

“…We need funding. Not just during an emergency, but throughout the school year…when we’re feeding our children and our counties, we should not be struggling to fund our program. But now, all this money has come up to help us do what we’re doing. We need it during the school year, too, because a lot of the [programs] are struggling. A lot of people don’t know that we get no funding except for our reimbursement on our free/reduced meals. And that barely covers just the meals and the labor. But then you’ve got employee benefits to pay… If we are state-employed, we should be getting state funding for those benefits, not coming out of the school nutrition budget, where we could do more for our children, and offer more, higher-quality products. It’s a shame you have to look when you’re doing your menu, what can we afford, when we should be offering our best”. (Southwest, Rural)

4. Discussion

Our analysis of operations during COVID-19 shed new light on policy and practice efforts that could improve school nutrition programs beyond the pandemic. We constructed themes that reflected the innovation and resilience of school meal programs while in crisis mode. During the early months of the pandemic, when health and economic stability were threatened nationwide and food insecurity became a top concern, school food programs and their operators moved front and center [40,41,42,43]. Our study highlights the extent to which program directors in a Southeastern US state innovated, adapted, and stretched to prioritize the children they feed. We also identified contextual factors related to director characteristics, other stakeholders, and the inner and outer setting that influenced program operators’ ability to adapt and innovate during the pandemic.

SNDs were motivated to operate during the pandemic to continue meeting the needs of children in their school districts, to keep programs financially solvent, and to keep staff safe and employed. Their dedication, creativity, and leadership in the face of constantly evolving challenges reinforces findings across other qualitative studies [18,19,20,21,22,23]. We also identified the influence of directors’ existing relationships and prior experience with disasters-induced school closures. Flexibility and resilience were key themes in this and other recent studies [18,21,22]. The SNDs in our study were “bendy flexibles” who were able to “roll with it” despite all the challenges faced in procuring and distributing school meals.

Federal, state, and local actors and policy decisions often facilitated further SND flexibility; however, SNDs sometimes felt that these same entities put up roadblocks and/or failed to act in timely and maximally supportive ways. Using directors’ own words, we issue clear calls to action for policy and systems changes to continue to enable tailored innovations that strengthen program operations. Our findings corroborate other pandemic-era studies in other areas of the U.S. that reported on the importance of internal and external partnerships [19,20,21,22], and underscore the value of cultivating collaboration for community food security regardless of individual state or regional policy climate. In our study, new internal partnerships with other school district departments and personnel not only helped maintain operations, but also made staff feel more integrated into their districts. Thus, the strengthening of internal partnerships is an important innovation to carry forward to streamline operations and legitimize school nutrition. Steps should be taken to ensure that districts continue to align school nutrition efforts with other internal departments and to provide the necessary resources to do so. Further research should investigate the extent to which internal and external partnerships are maintained and formalized post-pandemic, identify strategies for sustaining them, and test their impact on local food systems more broadly.

More investigation is needed into the role of structural characteristics, particularly district size and geography, in hindering or enabling school meal operations. SNDs described various challenges during pandemic operations because of district size, but they also described the ways in which their size or locale facilitated creative solutions. A 2020 study used geospatial analysis to examine meal site placement in urban areas during COVID-19 and found more sites located in higher poverty, higher minority areas [44]. This study, as well as studies conducted prior to the pandemic in the summer months (when sites are placed in communities, not just schools), have primarily focused on urban areas [44,45,46,47,48]. Future research could integrate qualitative implementation data with mapping data [48] to investigate local factors that influence reach and implementation by rurality, district size, and other relevant geographic indicators, particularly as supply chain issues have persisted throughout the pandemic [49]. This could inform how preparation and delivery models could be tailored to meet local needs, both during emergency and non-emergency operations.

We expect future public health and climate-related disasters will require more frequent pivots to emergency operations. SNDs adapted swiftly in the early months of COVID-19, and steps should be taken to ensure more preparedness for future disasters. Our findings endorse suggestions from Patton et al. to develop training manuals, attend to employee safety concerns, increase speed of communication, use social media, and promote the role of school nutrition employees as “essential” for future preparedness [18]. Additional recommendations based on our findings include having resources readily available (e.g., maintaining storage infrastructure, allowing districts to retain more than the current limit of three months’ operating expenses), giving SNDs a seat with local leaders at the decision-making table, and maintaining contact information of local partners and other nearby school districts. Future preparedness also requires federal policy leniency and a budget for emergency operations [18,19,23], as USDA’s traditional reimbursement formula is, as described by Kenney et al., “untenable” during school closures [23].

SNDs in our study were nearly united in stating the potential positive influence of federal legislation to shift from the current model of having free, reduced, and paid meal categories to “healthy school meals for all,” regardless of household income. Informants in other qualitative empirical studies conducted during COVID-19, which have been conducted in states with varying political climates, have also endorsed healthy school meals for all, [21,23] as have various national advocacy organizations [50,51,52]. The United States Congress is tasked with Child Nutrition Reauthorization (CNR) every five years, an opportunity to improve regulations and systems that govern school nutrition programs. These policies have not been meaningfully updated since 2010. Opponents of healthy school meals for all have cited concerns around costs [7,8,9], the need to collect household income data for education funding [53], concerns about eroding meal nutrition standards [50,51,52], or have simply argued that the funding for the programs is adequate [51,52]. SNDs from North Carolina, as well as other states across the country [18,21,23], do not agree that funding is adequate, as many have felt that they have had to be too thrifty, sacrificing program quality. SNDs felt that healthy school meals for all could eliminate stigma and that reducing the administrative burden of collecting family income paperwork could free up staff time for meal preparation and funds to procure high-quality food locally. Our data sends a uniform message to federal policy makers from SNDs. As one of our SNDs stated, “We have asked for years for this program to be funded to feed all kids. If it’s ever going to happen, it needs to happen now”.

Finally, this and other studies document the heightened awareness and appreciation for school meal programs from other district personnel, community members, and the media during the early pandemic [18,19,20,21,22,23]. SNDs point to a potential culture shift around school nutrition, but the question remains how to keep the support and acknowledgement of value going as post-crisis systems resume. As part of this call to action, researchers, including our team, should prioritize better dissemination of research findings to non-research stakeholders (e.g., writing op-eds or creating policy briefs to share with congressional committees) to elevate SNDs’ experiences and translate those experiences to policy and practice change.

Our findings should be interpreted with consideration to several limitations. SNDs have highly demanding jobs during the best of times, and this was exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Even so, 23 SNDs participated in interviews at a time when stress and uncertainty were at an all-time high. These circumstances may have led us to a sample of directors particularly motivated to share their experiences and perspectives; thus, it is unclear whether our sample is representative of all North Carolina SNDs. Additionally, the perspectives of SNDs do not necessarily reflect the experiences of other school nutrition staff or students and families who received school meals. Future studies should investigate staff, student, and family perceptions of school meal programs during and beyond the pandemic to better inform policy decisions at all levels. Finally, although we included directors from diverse North Carolina regions, our sample does not allow us to explore differences by district size, geography, or length of the directors’ tenure. Some directors indicated important differences in how these factors influenced pandemic-related experiences and program operations, which warrants further exploration.

5. Conclusions

School nutrition programs faced numerous operational challenges during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic yet continued serving meals via innovative methods and partnerships as a result of USDA waivers. Through this study, we identified multi-level factors that influenced the success of these innovations, including characteristics of the SNDs themselves, characteristics of internal and external stakeholders, the district and community (inner setting), and the state and policy climate (outer setting). As stakeholders like USDA, state and federal policy makers, and program operators contemplate expanding school nutrition programs based on COVID-related innovations, they should be mindful of the multi-level factors that our SNDs identified as crucial to ensuring that programs realize their full potential as hubs of resilience within community food systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph19137650/s1, Supplemental File S1. Interview guide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.N.K., J.S., S.J.P., A.S.A. and H.G.L.; methodology, H.G.L.; formal analysis, B.N.K., J.S., K.G., S.J.P., S.L.M., L.T. and H.G.L.; investigation, B.N.K.; J.S. and H.G.L.; writing—original draft preparation, B.N.K. and H.G.L.; writing—review and editing, B.N.K.; J.S., K.G., S.J.P., S.L.M., L.T., A.S.A. and H.G.L., supervision, H.G.L.; project administration, K.G.; funding acquisition, B.N.K., J.S., A.S.A. and H.G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the a COVID-19 Pilot Grant through the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute (funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences [NCATS], National Institutes of Health [Grant ID: UL1TR002489]) and a K12 Career Development Award through Duke University Department of Population Health Sciences Dissemination and Implementation Science for Cardiovascular Outcomes (DISCO) award (funded by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute [NHLBI], National Institutes of Health [Grant ID: K12HL138030]).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Duke University Health System (protocol code Pro00105480, approved exempt, 23 April 2020) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Portions of de-identified data from qualitative datasets may be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We offer our deepest gratitude to the school nutrition directors who spent valuable time speaking with us about their experiences during an extraordinarily challenging period. We are thankful to our colleagues at the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction for their assistance with recruitment and their support of this research. Thanks to the Carolina Hunger Initiative team for offering resources and support and to our research assistants for assisting with data collection and/or coding. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the tremendous contribution all school nutrition staff and volunteers have made to our communities throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. We appreciate the opportunity to learn from them and to be inspired by their dedication to keeping our nation’s children fed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Richard, B. Russell National School Lunch Act of 1946; Public Law 79-396; U.S. Statutes at Large; 1946; Volume 230, pp. 230–234. Available online: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/pl_79-386.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- National School Lunch Program: Total Participation. Available online: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/01slfypart-5.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service The National School Lunch Program Fact Sheet. Available online: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/NSLPFactSheet.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Cohen, J.F.W.; Hecht, A.A.; McLoughlin, G.M.; Turner, L.; Schwartz, M.B. Universal School Meals and Associations with Student Participation, Attendance, Academic Performance, Diet Quality, Food Security, and Body Mass Index: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girouard, D.; FitzSimons, C. Reducing Barriers to Consuming School Meals; Food Research & Action Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- No Kid Hungry Universal School Meals: Comparing Funding Options to Create Hunger-Free Schools. Available online: https://bestpractices.nokidhungry.org/sites/default/files/providing-universal-free-school-meals_0.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Bakst, D.; Butcher, J. Why Isn’t the School Meal Program Serving Only Those in Need? Available online: https://www.heritage.org/agriculture/commentary/why-isnt-the-school-meal-program-serving-only-those-need (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Eden, M. The Case Against Universal Free Lunch; American Enterprise Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bakst, D.; Butcher, J. Congress Has to Avoid Universal Free School Meals Which Include Wealthy. Hill 2020. Available online: https://thehill.com/opinion/education/513365-congress-has-to-avoid-universal-free-school-meals-which-include-wealthy/ (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- School Meals. Available online: https://www-usda-gov.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/coronavirus/school-meals#:~:text=However%2C%20the%20waiver%20authority%20provided,the%20FNS%20COVID%2D19%20webpage (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- The Council of State Governments 2020-2021 State Executive Orders. Available online: https://web.csg.org/covid19/executive-orders/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Kline, A. Nationwide Waiver to Extend Unanticipated School Closure Operations through June 30, 2020. Available online: https://www-fns-usda-gov.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/cn/covid-19-child-nutrition-response-21 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Child Nutrition COVID-19 Waivers. Available online: https://www-fns-usda-gov.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/fns-disaster-assistance/fns-responds-covid-19/child-nutrition-covid-19-waivers (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Kinsey, E.W.; Hecht, A.A.; Dunn, C.G.; Levi, R.; Read, M.A.; Smith, C.; Niesen, P.; Seligman, H.K.; Hager, E.R. School closures during COVID-19: Opportunities for innovation in meal service. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 1635–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gecker, J. California Launches Largest Free School Lunch Program in US. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/politics/articles/2021-07-19/california-launches-largest-free-school-lunch-program-in-us (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Balingit, M. Schools Serve More than 20 Million Free Lunches Every Day. If They Close, Where Will Children Eat? The Washington Post, 16 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, E.G. These Unsung Heroes of Public School Kitchens Have Fed Millions. The New York Times, 15 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Patten, E.V.; Spruance, L.; Vaterlaus, J.M.; Jones, M.; Beckstead, E. Disaster Management and School Nutrition: A Qualitative Study of Emergency Feeding During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 1441–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jowell, A.H.; Bruce, J.S.; Escobar, G.V.; Ordonez, V.M.; Hecht, C.A.; Patel, A.I. Mitigating childhood food insecurity during COVID-19: A qualitative study of how school districts in California’s San Joaquin Valley responded to growing needs. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, B.L.; Gans, K.M.; Burkholder, K.; Esposito, J.; Warykas, S.W.; Schwartz, M.B. Distributing Summer Meals during a Pandemic: Challenges and Innovations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, K.; Babbin, M.; McKee, S.; McGinn, K.; Cohen, J.; Chafouleas, S.; Schwartz, M. Dedication, innovation, and collaboration: A mixed-methods analysis of school meals in Connecticut during COVID-19. JAFSCD 2021, 10, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.V.; Gross, J.; Harper, K.M.; Medina-Perez, K.; Wilson, M.J.; Gross, S.M. Serving Summer Meals During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study of 2 Summer Food Service Program Sponsors in Maryland. J. Sch. Health 2022, 92, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenney, E.L.; Dunn, C.G.; Mozaffarian, R.S.; Dai, J.; Wilson, K.; West, J.; Shen, Y.; Fleischhacker, S.; Bleich, S.N. Feeding Children and Maintaining Food Service Operations during COVID-19: A Mixed Methods Investigation of Implementation and Financial Challenges. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. September 2019—February 2020 Meal Claims Data; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Child Population by Age Group in North Carolina. Available online: https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/6169-child-population-by-age-group#detailed/2/any/false/574,1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867/158,137,138,182,838,392,440/12869 (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Percent of Students Enrolled in Free and Reduced Lunch. Available online: https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/2239-percent-of-students-enrolled-in-free-and-reduced-lunch#detailed/2/any/false/1769,1696,1648,1603,1539,1381,1246,1124,1021,909/any/4682 (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- School Breakfast Program: Total Participation. Available online: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/08sbfypart-5.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Governor Cooper Issues Executive Order Closing K-12 Public Schools and Banning Gatherings of More Than 100 People. Available online: https://governor.nc.gov/news/governor-cooper-issues-executive-order-closing-k-12-public-schools-and-banning-gatherings-more (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- COVID-19 Timeline. No Kid Hungry, NC. Available online: http://nokidhungrync.org/covid19-timeline (accessed on 26 May 2022).

- HER NOPREN COVID-19 Food and Nutrition Work Group|Nutrition and Obesity Policy Research and Evaluation Network. Available online: https://nopren.ucsf.edu/her-nopren-covid-19-food-and-nutrition-work-group (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview guides: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979; p. 352. ISBN 0674224566. [Google Scholar]

- The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research—Technical Assistance for Users of the CFIR Framework. Available online: https://cfirguide.org/ (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Saldana, J.; Omasta, M. Qualitative Research: Analyzing Life, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; p. 472. ISBN 1506305490. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; p. 408. ISBN 9781506353081. [Google Scholar]

- Common Core of Data. United States Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- About Us. North Carolina Rural Center. Available online: https://www.ncruralcenter.org/about-us/ (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- North Carolina Department of Public Instruction State Board Extends Emergency Sick Leave Policy; Cancels 2020 Governor’s School. Available online: https://www.dpi.nc.gov/news/press-releases/2020/04/30/state-board-extends-emergency-sick-leave-policy-cancels-2020-governors-school (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Coronavirus Relief Fund—School Nutrition—PRC 125 Guidance for Allowable Use of Funds. Available online: https://www.dpi.nc.gov/media/8321/download (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Dunn, C.G.; Kenney, E.; Fleischhacker, S.E.; Bleich, S.N. Feeding low-income children during the COVID-19 pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrells, A. NC Summer Meals Innovate in Face of Uncertainty. Available online: https://www.ednc.org/covid-19-summer-meals-efforts-innovate-uncertainty/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Childress, G. NC’s Already Dire Childhood Hunger Problem Has Gotten a Lot Worse. Available online: https://ncpolicywatch.com/2020/05/22/ncs-already-dire-childhood-hunger-problem-has-gotten-a-lot-worse/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Hinchcliffe, K. Despite Closures, Schools Providing Food to NC Kids during Pandemic. Available online: https://carolinapublicpress.org/30145/despite-closures-schools-providing-food-to-nc-kids-during-pandemic/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- McLoughlin, G.M.; McCarthy, J.A.; McGuirt, J.T.; Singleton, C.R.; Dunn, C.G.; Gadhoke, P. Addressing Food Insecurity through a Health Equity Lens: A Case Study of Large Urban School Districts during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Urban Health 2020, 97, 759–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, L.; O’Reilly, N.; Ralston, K.; Guthrie, J.F. Identifying gaps in the food security safety net: The characteristics and availability of summer nutrition programmes in California, USA. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1824–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLoughlin, G.M.; Fleischhacker, S.; Hecht, A.A.; McGuirt, J.; Vega, C.; Read, M.; Colón-Ramos, U.; Dunn, C.G. Feeding students during COVID-19-related school closures: A nationwide assessment of initial responses. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litt, H.; Polke, A.; Tully, J.; Volerman, A. Addressing Food Insecurity: An Evaluation of Factors Associated with Reach of a School-Based Summer Meals Program. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 1715–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieber-Emmons, A.M.; Miller, W.L.; Rubinstein, E.B.; Howard, J.; Tsui, J.; Rankin, J.L.; Crabtree, B.F. A novel mixed methods approach combining geospatial mapping and qualitative inquiry to identify multilevel policy targets: The focused rapid assessment process (frap) applied to cancer survivorship. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2022, 16, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patten, E.V.; Beckstead, E.; Jones, M.; Spruance, L.A.; Hayes, D. School Nutrition Professionals’ Employee Safety Experiences During the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nixon, L.; Gardin, K.; Seklir, L.; Gottleib, M.; Dorfman, L. Examining the Public Debate on School Food Nutrition Guidelines: Findings and Lessons Learned from An Analysis of News Coverage and Legislative Debates; Berkeley Media Studies Group: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- American Heart Association Policy Statement on School Nutrition. Available online: https://www.heart.org/-/media/files/get-involved/advocacy/policy-statement-on-school-nutrition-june-2020.pdf?la=en (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- School Nutrition Association 2022 Position Paper. Available online: https://schoolnutrition-org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/legislation-policy/action-center/2022-position-paper/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Hecht, A.A.; Dunn, C.G.; Turner, L.; Fleischhacker, S.; Kenney, E.; Bleich, S.N. Improving Access to Free School Meals: Addressing Intersections between Universal Free School Meal Approaches and Educational Funding; Healthy Eating Research: Durham, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).