A Qualitative Investigation of the Experiences of Tobacco Use among U.S. Adults with Food Insecurity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

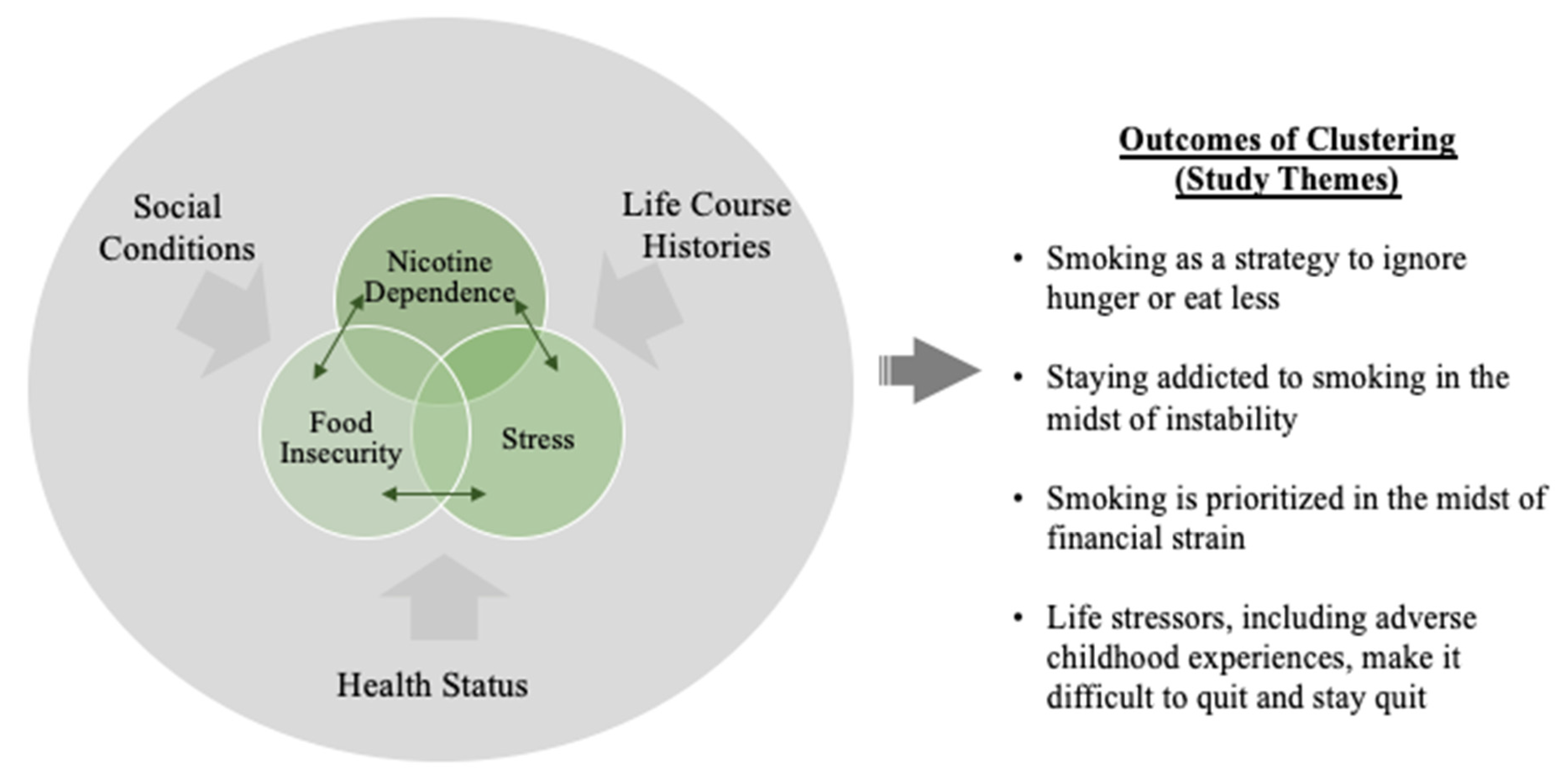

Structural Marginalization, Food Insecurity, and Tobacco Use

- Theme 1: Smoking to ignore hunger or eat less

[Smoking] takes away my appetite. Because of growing up and not having food and stuff like that, I kind of don’t necessarily feel hunger, like I block it out. But it’s obviously there. My body’s hungry, it would like to eat. But on the times that I do feel hungry, if I smoke a cigarette, it goes away…I think I smoke more on the days I don’t eat, specifically if they’ve been multiple days, like more than one day in a row that I haven’t eaten. I definitely smoke more to combat that.(Julie, female participant in mid 40s)

So the instant gratification of the cigarette makes it so that I automatically stop feeling hungry at that moment. And it’ll last for, I think about an hour. I’ll usually get an hour, like if I don’t have food [by] then, I’ll smoke again. If I have something to eat [in the house], I might eat.(Lisa, female participant in mid 30s)

I’m already a chubby girl, so it was just like I was really huge within two months. It was insane… And it became a greater risk factor, you know, having the diabetes and the hypertension and then the extra added weight. So it was just like ‘Well, you want me to lose weight, it’s kind of hard to do that if I’m not smoking.’ And then I tried the gym, and that just wasn’t working for me. It didn’t fit into my time. My life time of just trying to work, the kids, appointments, meetings… And so I started smoking again. I started smoking because I was stressed out, and I started smoking, and I started losing the weight all over again. It’s crazy because the cigarettes—the cigarettes sometimes replace a meal for me, almost.(Jasmine, female participant in mid 30s)

- Theme 2: Staying addicted to smoking in the midst of instability

[I feel] a little bit guilty because I know that I shouldn’t be smoking cigarettes. I know that. And like, I also have physical problems that are worse because I smoke. And like I know that, like, I’m making that choice even though, yeah, I’m addicted to nicotine but I’m making a choice not to give it up so I feel guilty.(Mel, female participant in early 30s)

I think an important point that I would like to make is that I sacrifice food [for myself] for my daughter, but for some reason I would not sacrifice cigarettes for food for myself, and I don’t know why that is.

I always say, ‘Yeah, someday [I’ll quit], but today’s not that day.’ Back in the end of February, I believe, I was sick and I went to—I think it was one of the urgent care places. And they did x-rays and found spots on my lungs. And every time I lit up a cigarette, I’m thinking to myself, yeah, what are you doing? This isn’t okay. But I would still light up and smoke the cigarette.(Julie, female participant in mid 40s)

It’s basically so when my son mentions anything, like he’s told me once that he wants me to quit smoking cigarettes. Just once. But the thing that twinges at my heart strings or makes me feel really crappy is when I’m going to go outside to have a cigarette and he’s like ‘Mommy, are you going out to have a cigarette?’ He’s 7 years old. He shouldn’t—cigarette is not an easy word to say. It shouldn’t be a normal word in his vocabulary and that kind of makes me feel like a really shitty mom. I know that’s not the case, but you know.(Anne, female participant in late 20s)

Like I probably will take [USD] $20 out of [child support] a week. I’ll buy a couple of packs out of the money but I try—I don’t like doing that because then I feel even guiltier about the guilt I feel on top of when I go smoke a cigarette and the kids are ‘No. You’re my mom. I don’t want you to smoke.’ And also using some of the money that’s designated for their care.(Jan, female participant in mid 30s)

- Theme 3: Smoking gets prioritized in the midst of financial strain

Interviewer: I know you said you’re unemployed right now and you’re on a limited income, but how do cigarettes factor into your budget? How do you organize your budget?

John: Well, I actually roll my own cigarettes now, so it’s cheaper. It’s a lot cheaper actually. If I had to pay for regular cigarettes, I couldn’t do it… I spend about $100 a month… I was spending almost $100 a week. Because I roll them it’s only like $100 for the whole month… I’m pretty much locked into the same price all the time, you know?

People that are in my situation have financial burdens with the food and everything. But smoking is a big thing and at one point, yes, it’s expensive and it takes a lot out of your budget. But it also takes the worry away too.(John, male participant in early 50s)

Anne: So I think cigarettes are the only thing that I, for sure, make sure to budget every month. Like that is the constant.

Interviewer: You make a budget?

Anne: Yes. That’s like the only thing that I can successfully budget. And it’s sad to say because I should be able to successfully budget anything if I can budget that into my very little income that I was having.

Well, I just counted it like a bill. So on the first, you know, when I got paid, I would go to New Hampshire and buy them for the month, so basically I just acted like it was the cable bill, but it was my cigarette habit bill.(Tina, female participant in mid 40s)

I do try to smoke less when I know I’m going to be like completely broke…Like, I try to. It’s hard. Like I often get stressed out about the fact that I don’t have enough money for everything I need. And that just makes me want to smoke more.(Mel, female participant in early 30s)

- Theme 4: Life stressors and the difficulty of quitting smoking and staying quit

After I quit the last time before the surgery that should have been it. But then we moved and all of the money [I saved] was stolen and it could have been stolen by someone we lived with. So that was stressful because these are people I was supposed to trust. And once we moved into our own apartment, the stress of moving into our own apartment died down I quit again. And it was for a few months. And we found out our friend needed a place to stay and he was going to be staying with us and I immediately started smoking again because I have social anxiety. So a really small apartment with an extra person just kind of put me in a place where it wasn’t my normal self. So smoking helps.(Lisa, female participant in mid 30s)

Before this last time that I attempted to quit, I knew that I would be able to quit if I could have three days off, of no work, no school, no responsibility, and just sleep because the first three days are the hardest. So I had asked my sister like, ‘Hey, I want to try and quit smoking. Is there any way that I can have you have [my son] for a day and a half so I can just sleep? And she’s like ‘No, that’s not good for you or for him.’ And like she doesn’t understand.(Anne, female participant in late 20s)

Interviewer: What type of help or support would you want for quitting?

Deb: I want to go into a hospital or a place of healing, in therapy or whatever, for five days. Get away from everything in my life and just leave me alone and just give me a week to detox from it, right? I’ll go to meetings of support or whatever, because I’ve been through addiction habits of other substances, right, and I’ve been able to kick those things…

I was using heroin for a short time in my life. And I was an IV drug user. This was before I had my son. And I quit that and I had gotten on methadone and I even quit that with no help and never picked up dope again. But yet, quitting cigarettes seems so impossible… there was a time where I went a few days without smoking, but I was around people who were not smoking and I had support and medical care. But I feel like I cannot do it unless I get a break from everybody, be by myself and build up the strength. When you’re under a constant stressful situation, it seems impossible.

Interviewer: What are your thoughts about quitting right now?

Jasmine: So I want to. I actually just met with a woman a few days ago to get a Y membership [referring to the YMCA, a nonprofit organization with locations across the U.S. that has workout facilities and offers fitness classes] for me and the family. I just need—I need a lot. I don’t know how the typical person stops smoking, but I feel like my life is always surrounded by stress. And the only way to really stop smoking is to remove that, and that’s like impossible. So I guess one would be me learning how to cope with the stress first. This way, when stress arises, then I’m able to cope with it enough where I don’t need a cigarette.

- Theme 5: Childhood adversity at intersection of current food insecurity and tobacco use

I grew up with parents that were smokers, alcoholics, so it was always around us. That’s why addiction and smoking started early with me. It was always around us. My father was very abusive so my mother ended up leaving my father… And it wasn’t until later that I realized you don’t give teenagers or your children beer and liquor and cigarettes and stuff. So I felt like my addictions were never my choice. Somebody else made the choice for me to be an addict, because a child doesn’t choose to be an addict.(Jenny, female participant in late 40s)

My mom, she had three daughters and she was trying to support us but we had to go without a lot of times. Like any new clothes or shoes that I got weren’t new. I had gotten them from friends at school. It’s just like, disheartening to feel that you just don’t have enough to get your basic needs. And so like when I wasn’t working so much because it was a good few months or more, and it was just really disheartening because it’s like my son would want something and I had to say no because I don’t have the money. I just don’t have the money for it. I’m now getting my hours back. But catching up is really hard. Trying to have a good birthday for my son, if it wasn’t for a good friend of mine, like my son probably wouldn’t have had a birthday. Yeah. It’s tough.(Anne, female participant in late 20s)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking Cessation. A Report of the Surgeon General; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- Cornelius, M.E.; Wang, T.W.; Jamal, A.; Loretan, C.G.; Neff, L.J. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1736–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creamer, M.R.; Wang, T.W.; Babb, S.; Cullen, K.A.; Day, H.; Willis, G.; Jamal, A.; Neff, L. Tobacco Product Use and Cessation Indicators Among Adults—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Babb, S.; Malarcher, A.; Asman, K.; Jamal, A. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 65, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotz, D.; West, R. Explaining the social gradient in smoking cessation: It’s not in the trying, but in the succeeding. Tob. Control 2009, 18, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkhoran, S.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Rigotti, N.A.; Baggett, T.P. Financial strain, quit attempts, and smoking abstinence among U.S. adult smokers. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, 80–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendzor, D.E.; Businelle, M.S.; Costello, T.J.; Castro, Y.; Reitzel, L.R.; Cofta-Woerpel, L.M.; Li, Y.; Mazas, C.A.; Vidrine, J.I.; Cinciripini, P.M.; et al. Financial strain and smoking cessation among racially/ethnically diverse smokers. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.A.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2020; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; p. 55.

- Poghosyan, H.; Moen, E.L.; Kim, D.; Manjourides, J.; Cooley, M.E. Social and structural determinants of smoking status and quit attempts among adults living in 12 US states, 2015. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 33, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, M.; Gueorguieva, R.; Ma, X.; White, M.A. Tobacco use increases risk of food insecurity: An analysis of continuous NHANES data from 1999 to 2014. Prev. Med. 2019, 126, 105765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Mozeleski, J.E.; Pandey, R. The intersection of food insecurity and tobacco use: A scoping review. Health Promot. Pract. 2020, 21, 124S–138S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsoh, J.Y.; Hessler, D.; Parra, J.R.; Bowyer, V.; Lugtu, K.; Potter, M.B. Addressing tobacco use in the context of complex social needs: A new conceptual framework and approach to address smoking cessation in community health centers. PEC Innov. 2021, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; McQueen, A.; Roberts, C.; Butler, T.; Grimes, L.M.; Thompson, T.; Caburnay, C.; Wolff, J.; Javed, I.; Carpenter, K.M.; et al. Stress, depression, sleep problems and unmet social needs: Baseline characteristics of low-income smokers in a randomized cessation trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2021, 24, 100857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frohlich, K.L.; Poland, B.; Mykhalovskiy, E.; Alexander, S.; Maule, C. Tobacco control and the inequitable socio-economic distribution of smoking: Smokers’ discourses and implications for tobacco control. Crit. Public Health 2010, 20, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, K.L.; Potvin, L. Transcending the Known in Public Health Practice: The Inequality Paradox: The Population Approach and Vulnerable Populations. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahpush, M.; Borland, R.; Yong, H.-H. Sociodemographic and psychosocial correlates of smoking-induced deprivation and its effect on quitting: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey. Tob. Control 2007, 16, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, S.D.; Golden, S.D.; O’Leary, M.C.; Logan, P.; Lich, K.H. Using systems science to advance health equity in tobacco control: A causal loop diagram of smoking. Tob. Control 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9, 26152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baum, F.; Fisher, M. Why behavioural health promotion endures despite its failure to reduce health inequities. Sociol. Health Illn. 2014, 36, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Mozeleski, J.E.; Poudel, K.C.; Tsoh, J.Y. Examining Reciprocal Effects of Cigarette Smoking, Food Insecurity, and Psychological Distress in the U.S. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2021, 53, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.F.; Ma, G.X.; Miranda, J.; Eng, E.; Castille, D.; Brockie, T.; Jones, P.; Airhihenbuwa, C.O.; Farhat, T.; Zhu, L.; et al. Structural Interventions to Reduce and Eliminate Health Disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, S72–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Dillard, R.; Kobulsky, J.; Nemeth, J.; Shi, Y.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S. The Type and Timing of Child Maltreatment as Predictors of Adolescent Cigarette Smoking Trajectories. Subst. Use Misuse 2020, 55, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leddy, A.M.; Weiser, S.D.; Palar, K.; Seligman, H. A conceptual model for understanding the rapid COVID-19–related increase in food insecurity and its impact on health and healthcare. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagata, J.M.; Ganson, K.T.; Whittle, H.J.; Chu, J.; Harris, O.O.; Tsai, A.C.; Weiser, S.D. Food Insufficiency and Mental Health in the U.S. During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2021, 60, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, D.; Thomsen, M.R.; Nayga, R.M. The association between food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holingue, C.; Kalb, L.G.; Riehm, K.E.; Bennett, D.; Kapteyn, A.; Veldhuis, C.B.; Johnson, R.M.; Fallin, M.D.; Kreuter, F.; Stuart, E.A.; et al. Mental Distress in the United States at the Beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 1628–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yingst, J.M.; Krebs, N.M.; Bordner, C.R.; Hobkirk, A.L.; Allen, S.I.; Foulds, J. Tobacco Use Changes and Perceived Health Risks among Current Tobacco Users during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigotti, N.A.; Chang, Y.; Regan, S.; Lee, S.; Kelley, J.H.K.; Davis, E.; Levy, D.E.; Singer, D.E.; Tindle, H.A. Cigarette Smoking and Risk Perceptions During the COVID-19 Pandemic Reported by Recently Hospitalized Participants in a Smoking Cessation Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 3786–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 18 (78%) |

| Male | 5 (22%) |

| Age range | |

| 21–34 | 7 (30%) |

| 35–49 | 8 (35%) |

| 50–64 | 7 (30%) |

| 65 or older | 1 (4%) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| African American / Black | 3 (13%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (13%) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 15 (65%) |

| Another race or multiple races | 2 (9%) |

| Education level | |

| Less than 12 years | 3 (13%) |

| High school or GED | 7 (30%) |

| Some college | 3 (35%) |

| College degree or more | 5 (22%) |

| Smoking characteristics | |

| Smokes daily | 21 (91%) |

| Number of cigarettes in a typical day, M (SD, range) | 15 (8, 1–35) |

| Food insecurity indicators | |

| Worried about running out of food | 23 (100%) |

| Food didn’t last | 20 (87%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim-Mozeleski, J.E.; Shaw, S.J.; Yen, I.H.; Tsoh, J.Y. A Qualitative Investigation of the Experiences of Tobacco Use among U.S. Adults with Food Insecurity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127424

Kim-Mozeleski JE, Shaw SJ, Yen IH, Tsoh JY. A Qualitative Investigation of the Experiences of Tobacco Use among U.S. Adults with Food Insecurity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(12):7424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127424

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim-Mozeleski, Jin E., Susan J. Shaw, Irene H. Yen, and Janice Y. Tsoh. 2022. "A Qualitative Investigation of the Experiences of Tobacco Use among U.S. Adults with Food Insecurity" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 12: 7424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127424

APA StyleKim-Mozeleski, J. E., Shaw, S. J., Yen, I. H., & Tsoh, J. Y. (2022). A Qualitative Investigation of the Experiences of Tobacco Use among U.S. Adults with Food Insecurity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127424