Misophonia: A Systematic Review of Current and Future Trends in This Emerging Clinical Field

Abstract

1. Introduction

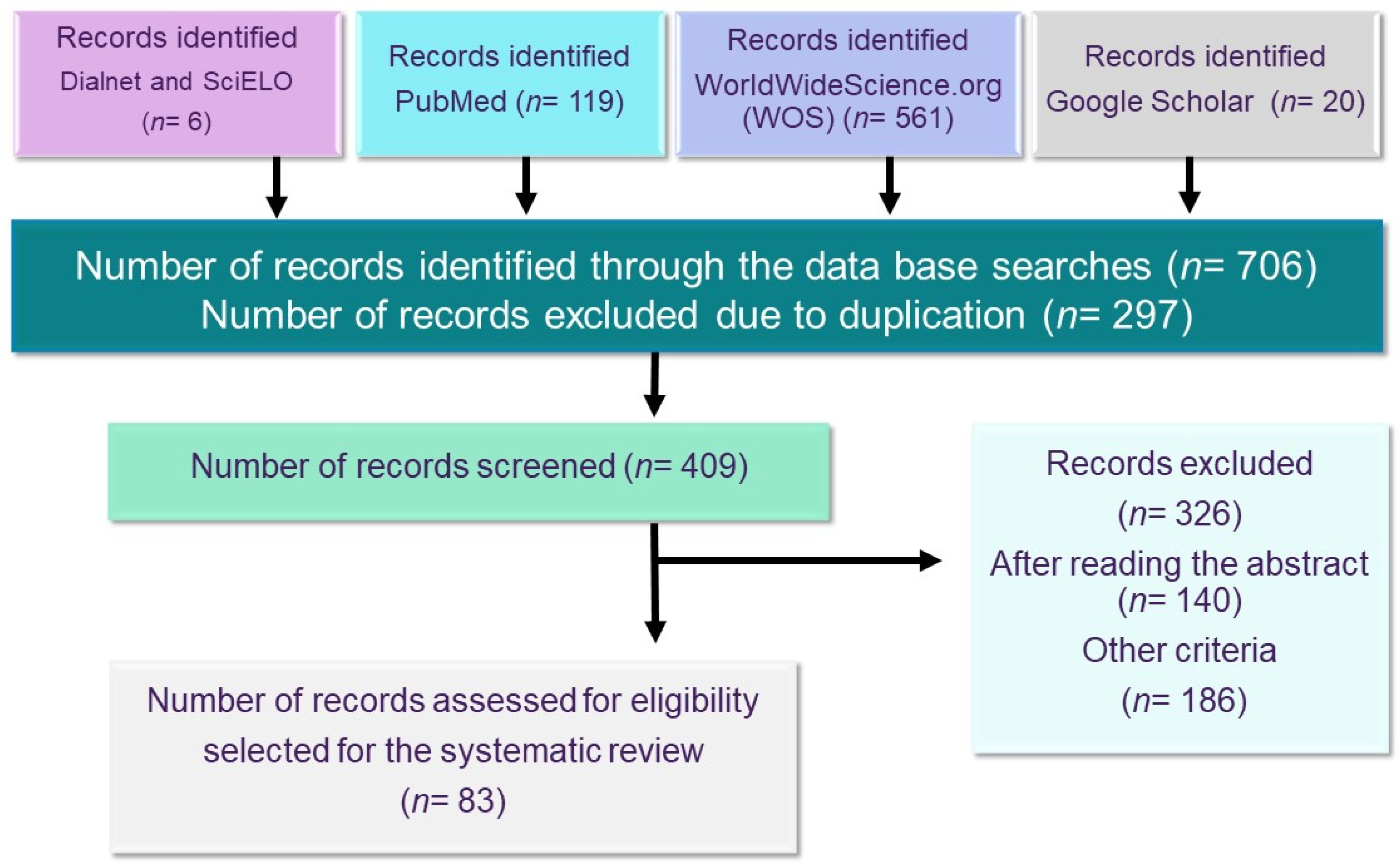

2. Methods

3. Results of the Bibliographic Research

3.1. Triggering or Misophonic Stimulus and Symptomatology

3.2. The Evolution of the Study of Misophonia

3.3. Epidemiology of Misophonia

3.4. Etiology of Misophonia

3.4.1. Genetic Predisposition Hypothesis

3.4.2. Neurobiological Alterations Hypothesis

3.4.3. Conditioning Hypothesis

3.5. Diagnosis of Misophonia

3.5.1. Diagnostic Criteria

3.5.2. Differential Diagnosis

3.6. Comorbidity

3.6.1. Misophonia and Associated Mental Disorders

3.6.2. Misophonia and Neurological and Auditory Disorders

3.7. Instruments and Procedure for the Assessment of Misophonia

3.7.1. Clinical Anamnesis

3.7.2. Audiological Evaluation

3.7.3. Self-Administered Scales of Misophonia

3.7.4. Emotional Assessment

3.7.5. Physiological Measurements

3.8. Treatment Options

3.8.1. Audiological Treatment

3.8.2. Pharmacological Treatment

3.8.3. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

3.8.4. Third-Generation Therapies

4. Discussion

4.1. On the Concept of Misophonia and Its Impact

4.2. The Diagnosis of Misophonia

- The presence or anticipation of a specific sensory experience such as a sound, vision or other stimulus of any sensory modality, intensity, and frequency.

- The triggering stimulus must be a conditioned stimulus.

- The stimulus of moderate duration (15”) elicits an immediate, reflexive, physical response.

- Dysregulation of potentially aggressive emotions and thoughts, recognizing these as illogical and negative.

- Avoidant and flight behaviors interfering in the person’s life.

4.3. The Differential Diagnosis and the Comorbidities

4.4. Instruments and Tools

4.5. Treatments

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brout, J.J.; Edelstein, M.; Erfanian, M.; Mannino, M.; Miller, L.J.; Rouw, R.; Rosenthal, M.Z. Investigating Misophonia: A Review of the Empirical Literature, Clinical Implications, and a Research Agenda. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelstein, M.; Brang, D.; Rouw, R.; Ramachandran, V.S. Misophonia: Physiological investigations and case descriptions. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jastreboff, M.M.; Jastreboff, P.J. Decreased Sound Tolerance and Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT). Aust. N. Z. J. Audiol. 2002, 24, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, M.M.; Jastreboff, P.J. Treatments for decreased sound tolerance (hyperacusis and misophonia). Semin. Hear. 2014, 35, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.S.; Lewin, A.B.; Murphy, T.K.; Storch, E.A. Misophonia: Incidence, Phenomenology, and Clinical Correlates in an Undergraduate Student Sample: Misophonia. J. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 70, 994–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepsiak, M.; Dragan, W. Misophonia—A Review of Research Results and Theoretical Conceptions. Psychiatr. Polska 2019, 53, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, E.C.; Rodriguez, A.; Zabelina, D.L. Severity of misophonia symptoms is associated with worse cognitive control when exposed to misophonia trigger sounds. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassiello-Robbins, C.; Anand, D.; McMahon, K.; Brout, J.; Kelley, L.; Rosenthal, M.Z. A preliminary investigation of the association between misophonia and symptoms of psychopathology and personality disorders. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S. Misophonia: A new mental disorder? Med. Hypotheses 2017, 103, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, A.R. Misophonia, Phonophobia, and Exploding Head Syndrome. In Textbook of Tinnitus; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duddy, D.F.; Oeding, K.A.M. Misophonia: An Overview. Semin. Hear. 2014, 35, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Torres, A.; Giménez-Llort, L. Confinement and the Hatred of Sound in Times of COVID-19: A Molotov Cocktail for People with Misophonia. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potgieter, I.; MacDonald, C.; Partridge, L.; Cima, R.; Sheldrake, J.; Hoare, D.J. Misophonia: A scoping review of research. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 75, 203–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, J.; Caimino, C.; Scutt, P.; Hoare, D.J.; Baguley, D.M. The Prevalence and Severity of Misophonia in a UK Undergraduate Medical Student Population and Validation of the Amsterdam Misophonia Scale. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 92, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetta, R.E.; Cassiello-Robbins, C.; Trumbull, J.; Anand, D.; Rosenthal, M.Z. Examining emotional functioning in misophonia: The role of affective instability and difficulties with emotion regulation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedo, S.E.; Baguley, D.M.; Denys, D.; Dixon, L.J.; Erfanian, M.; Fioretti, A.; Jastreboff, P.J.; Kumar, S.; Rosenthal, M.Z.; Rouw, R.; et al. Consensus Definition of Misophonia: A Delphi Study. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 224, 841816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, M.M.; Jastreboff, P.J. Components of decreased sound tolerance: Hyperacusis, misophonia, phonophobia. ITHS News Lett. 2001, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Torres, A.; Giménez-Llort, L. Sounds of Silence in Times of COVID-19: Distress and Loss of Cardiac Coherence in People with Misophonia Caused by Real, Imagined or Evoked Triggering Sounds. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 638949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, A.; Vulink, N.; Denys, D. Misophonia: Diagnostic Criteria for a New Psychiatric Disorder. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, P.; Leyendecker, J.; Conlon, M. Hyperacusis and misophonia: The lesser-known siblings of tinnitus. Minn. Med. 2011, 94, 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, R.E.; Angell, K.L.; Dehle, C.M. A brief course of cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of misophonia: A case example. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2013, 6, E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, T.G.; Da Silva, F.E. Familial misophonia or selective sound sensitivity syndrome: Evidence for autosomal dominant inheritance? Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 84, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo, D.B.; Alsalman, O.; De Ridder, D.; Song, J.-J.; Vanneste, S. Misophonia and Potential Underlying Mechanisms: A Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassiello-Robbins, C.; Anand, D.; McMahon, K.; Guetta, R.; Trumbull, J.; Kelley, L.; Rosenthal, M.Z. The mediating role of emotion regulation within the relationship between neuroticism and misophonia: A preliminary investigation. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, H.A.; Leber, A.B.; Saygin, Z.M. What sound sources trigger misophonia? Not just chewing and breathing. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 2609–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jastreboff, P.J.; Jastreboff, M.M. Tinnitus retraining therapy: A different view on tinnitus. ORL J. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Its Relat. Spec. 2006, 68, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanna, A.E.; Seri, S. Misophonia: Current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 2117–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozier, T.H.; Lopez, M.; Pearson, C. Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for Misophonia: A Multisensory Conditioned Aversive Reflex Disorder. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitoratou, S.; Uglik-Marucha, N.; Hayes, C.; Erfanian, M.; Pearson, O.; Gregory, J. Item Response Theory Investigation of Misophonia Auditory Triggers. Audiol. Res. 2021, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, M.S.; Storch, E.A. Misophonia symptoms among Chinese university students: Incidence, associated impairment, and clinical correlates. J. Obs.-Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2017, 14, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeoch, P.D.; Rouw, R. How everyday sounds can trigger strong emotions: ASMR, misophonia and the feeling of wellbeing. BioEssays 2020, 42, 2000099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J. β-Blockers for the Treatment of Misophonia and Misokinesia. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 45, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quek, T.; Ho, C.; Choo, C.; Nguyen, L.; Tran, B.; Ho, R. Misophonia in Singaporean Psychiatric Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozier, T.H. Etiology, composition, development and maintenance of misophonia: A conditioned aversive reflex disorder. Psychol. Thought 2015, 8, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunç, S.; Başbuğ, H.S. An extreme physical reaction in misophonia: Stop smacking your mouth. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 27, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, C.; Vidal, L.M.; Lage, M. Misophonia: Case report. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 41, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, C.; Öz, G.; Avanoğlu, K.B.; Aksoy, S. The prevalence and characteristics of misophonia in Ankara, Turkey: Population-based study. BJPsych Open 2021, 7, e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, A.; Vulink, N.; Van Loon, A.J.; Denys, D. Cognitive behavioral therapy is effective in misophonia: An open trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 217, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouw, R.; Erfanian, M. A Large-Scale Study of Misophonia. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 74, 453–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, T.A.; Johnson, P.L.; Storch, E.A. Pediatric misophonia with comorbid obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2014, 36, 231-e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguy, A.; Al-Humoud, A.M.; Pridmore, S.; Abuzeid, M.Y.; Singh, A.; Elsori, D. Low-Dose Risperidone for an Autistic Child with Comorbid ARFID and Misophonia. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2022, 52, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levitin, D.J.; Cole, K.; Lincoln, A.; Bellugi, U. Aversion, awareness, and attraction: Investigating claims of hyperacusis in the Williams syndrome phenotype. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2005, 46, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, A.; van Diepen, R.; Mazaheri, A.; Petropoulos-Petalas, D.; Soto de Amesti, V.; Vulink, N.; Denys, D. Diminished N1 Auditory Evoked Potentials to Oddball Stimuli in Misophonia Patients. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, A.; Giorgi, R.S.; Van Wingen, G.; Vulink, N.; Denys, D. Impulsive aggression in misophonia: Results from a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, A.; Wingen, G.V.; Eijsker, N.; San Giorgi, R.; Vulink, N.C.; Turbyne, C.; Denys, D. Misophonia is associated with altered brain activity in the auditory cortex and salience network. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Tansley-Hancock, O.; Sedley, W.; Winston, J.S.; Callaghan, M.F.; Allen, M.; Griffiths, T.D. The brain basis for misophonia. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eijsker, N.; Schröder, A.; Liebrand, L.C.; Smit, D.; Van Wingen, G.; Denys, D. White matter abnormalities in misophonia. NeuroImage Clin. 2021, 32, 102787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijsker, N.; Schröder, A.; Smit, D.J.; van Wingen, G.; Denys, D. Structural and functional brain abnormalities in misophonia. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 52, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Dheerendra, P.; Erfanian, M.; Benzaquén, E.; Sedley, W.; Gander, P.E.; Lad, M.; Bamiou, D.E.; Griffiths, T.D. The Motor Basis for Misophonia. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 5762–5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, A.; van Wingen, G.; Vulink, N.C.; Denys, D. Commentary: The Brain Basis for Misophonia. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, X.F.; Aboussssouan, A.; Mandell, D.; Huffman, K.L. Additional evidence supporting the central sensitization inventory (CSI) as an outcome measure among chronic pain patients in functional restoration program care. Spine J. Off. J. N. Am. Spine Soc. 2017, 17, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozier, T.H. Treating the Initial Physical Reflex of Misophonia with the Neural Repatterning Technique: A Counterconditioning Procedure. Psychol. Thought 2015, 8, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaja, C.S.; Abigail, M.S. Misophonia: An Evidence-Based Case Report. Am. J. Audiol. 2020, 29, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natalini, E.; Dimaggio, G.; Varakliotis, T. Misophonia, Maladaptive Schemas and Personality Disorders: A Report of Three Cases. Contemp. Psychother. 2020, 50, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, P.J.; Jastreboff, M.M. Decreased sound tolerance: Hyperacusis, misophonia, diplacousis, and polyacousis. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2015, 129, 375–387. [Google Scholar]

- Cusack, S.E.; Cash, T.V.; Vrana, S.R. An examination of the relationship between misophonia, anxiety sensitivity, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J. Obs.-Compuls. Relat. Disord. 2018, 18, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, J.; Hinds, J.; Camic, P.M. The well-being of allotment gardeners: A mixed methodological study. Ecopsychology 2015, 7, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, M.; Cavanna, A.E. Selective Sound Sensitivity Syndrome (Misophonia) in a Patient with Tourette Syndrome. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 25, E01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, B.; McKay, D. The suitability of an inhibitory learning approach in exposure when habituation fails: A clinical application to misophonia. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2019, 26, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, G.M.; Harrison, B.J.; Fontenelle, L.F. Hatred of sounds: Misophonic disorder or just an underreported psychiatric symptom? Ann. Clin. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Acad. Clin. Psychiatr. 2013, 25, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, F.E.; Sanchez, T.G. Evaluation of selective attention in patients with misophonia. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 85, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simner, J.; Koursarou, S.; Rinaldi, L.J.; Ward, J. Attention, flexibility, and imagery in misophonia: Does attention exacerbate everyday disliking of sound? J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2022, 43, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, J.E.; Kimball, S.H.; Nemri, D.C.; Ethridge, L.E. Toward a Multidimensional Understanding of Misophonia Using Cluster-Based Phenotyping. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 832516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochaut, D.; Lehongre, K.; Saitovitch, A.; Devauchelle, A.D.; Olasagasti, I.; Chabane, N.; Zilbovicius, M.; Giraud, A.L. Atypical coordination of cortical oscillations in response to speech in autism. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dar, R.; Kahn, D.T.; Carmeli, R. The relationship between sensory processing, childhood rituals and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2012, 43, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Conelea, C.A.; McKay, D.; Crowe, K.B.; Abramowitz, J.S. Sensory intolerance: Latent structure and psychopathologic correlates. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmura, M.J.; Monteith, T.S.; Anjum, W.; Doty, R.L.; Hegarty, S.E.; Keith, S.W. Olfactory function in migraine both during and between attacks. Cephalalgia 2014, 34, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M. Misophonia. Oregón Tinnitus y Hyperacusis Treatment Clinic, Inc. 21 September 2019. Available online: https://tinnitus-audiology.com/misophonia (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Burón, E.; Bulbena, A. Olfaction in affective and anxiety disorders: A review of the literature. Psychopathology 2013, 46, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, D.; Khemlani-Patel, S.; Neziroglu, F. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for an Adolescent Female Presenting with Misophonia: A Case Example. Clin. Case Stud. 2018, 17, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enzler, F.; Loriot, C.; Fournier, P.; Noreña, A.J. A psychoacoustic test for misophonia assessment. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepsiak, M.; Rosenthal, M.Z.; Raj-Koziak, D.; Dragan, W. Psychiatric and audiologic features of misophonia: Use of a clinical control group with auditory over-responsivity. J. Psychosom. Res. 2022, 156, 110777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelting, M.; Rienhoff, N.K.; Hesse, G.; Lamparter, U. The assessment of subjective distress related to hyperacusis with a self-rating questionnaire on hypersensitivity to sound. Laryngo-Rhino-Otol. 2002, 81, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herráiz, C.; Santos, G.D.L.; Diges, I.; Díez, R.; Aparicio, J.M. Assessment of hyperacusis: The self-rating questionnaire on hypersensitivity to sound. Acta Otorrinolaringol. Esp. 2006, 57, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzmaurice, G. The Misophonia Activation Scale (MAS-1). Available online: http://www.misophonia-uk.org/the-misophonia-activation-scale.html (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Kluckow, H.; Telfer, J.; Abraham, S. Should we screen for misophonia in patients with eating disorders? A report of three cases. Int. J. Eat. Dis. 2014, 47, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, D.; Kim, S.K.; Mancusi, L.; Storch, E.A.; Spankovich, C. Profile analysis of psychological symptoms associated with misophonia: A community simple. Behav. Ther. 2018, 49, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McErlean, A.B.J.; Banissy, M.J. Increased misophonia in self-reported autonomous sensory meridian response. PeerJ 2018, 6, e535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, N. Misophonia Physical Response Scale (MPRS). 2015. Misophonia Treatment Institute. Available online: https://misophoniatreatment.com/forms/ (accessed on 16 September 2021).

- Siepsiak, M.; Śliwerski, A.; Łukasz Dragan, W. Development and Psychometric Properties of MisoQuest-A New Self-Report Questionnaire for Misophonia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibb, B.; Golding, S.E.; Dozier, T.H. The development and validation of the Misophonia response scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 149, 110587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, M.Z.; Anand, D.; Cassiello-Robbins, C.; Williams, Z.J.; Guetta, R.E.; Trumbull, J.; Kelley, L.D. Development and Initial Validation of the Duke Misophonia Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, L.J.; Smees, R.; Ward, J.; Simner, J. Poorer Well-Being in Children with Misophonia: Evidence from the Sussex Misophonia Scale for Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 808379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, L.J.; Ward, J.; Simner, J. An Automated Online Assessment for Misophonia: The Sussex Misophonia Scale for Adults. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=An+Automated+Online+Assessment+for+Misophonia%3A+The+Sussex+Misophonia+Scale+for+Adults.+&btnG= (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Karin, J.; Hirsch, M.; Akselrod, S. An estimate of fetal autonomic sate by spectral analysis of fetal heart rate fluctuations. Pediatr. Res. 1993, 34, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarigedik, E.; Yurteri, N. Misophonia Successfully Treated of with Fluoxetine: A Case Report. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2021, 44, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, J.B.; Herzfeld, M. Tinnitus, Hyperacusis, and Misophonia Toolbox. Semin. Hear. 2014, 35, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zitelli, L. Evaluation and Management of Misophonia Using a Hybrid Telecare Approach: A Case Report. Semin. Hear. 2021, 42, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osuagwu, C.; Osuagwu, F.C.; Machoka, A.M. Methylphenidate Ameliorates Worsening Distractibility Symptoms of Misophonia in an Adolescent Male. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020, 22, 27485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jager, I.J.; Vulink, N.C.; Bergfeld, I.O.; van Loon, A.J.; Denys, D.A. Cognitive behavioral therapy for misophonia: A randomized clinical trial. Depress. Anxiety 2021, 38, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarotti, N.; Tuthill, A.; Fisher, P. Online Emotion Regulation for an Adolescent with Misophonia: A Case Study. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, J.F.; Wu, M.S.; Storch, E.A. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for 2 youths with misophonia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 76, 573–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamody, R.C.; Del Conte, G.S. Using Dialectical Behavior Therapy to Treat Misophonia in Adolescence. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2017, 19, 26256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, A.B.; Dickinson, S.; Kudryk, K.; Karlovich, A.R.; Harmon, S.L.; Phillips, D.A.; Tonarely, N.A.; Gruen, R.; Small, B.; Ehrenreich-May, J. Transdiagnostic cognitive behavioral therapy for misophonia in youth: Methods for a clinical trial and four pilot cases. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 291, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roushani, K.; Mehrabizadeh Honarmand, M. The Effectiveness of Cognitive-behavioral Therapy on Anger in Female Students with Misophonia: A Single-Case Study. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 46, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Aazh, H.; Landgrebe, M.; Danesh, A.A.; Moore, B.C. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Alleviating the Distress Caused by Tinnitus, Hyperacusis and Misophonia: Current Perspectives. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D. A Practical Guide to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.C. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behav. Ther. 2004, 35, 639–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, R.L.; Arch, J.J. Letter to the editor: Potential treatment targets for misophonia. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2015, 37, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, R.L.; Arch, J.J.; Wolitzky-Taylor, K.B. The state of personalized treatment for anxiety disorders: A systematic review of treatment moderators. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 38, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, I.; Vulink, N.; de Roos, C.; Denys, D. EMDR therapy for misophonia: A pilot study of case series. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1968613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, D. A compelling desire for deafness. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 2006, 11, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jager, I.; de Koning, P.; Bost, T.; Denys, D.; Vulink, N. Misophonia: Phenomenology, comorbidity and demographics in a large sample. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruxner, G. ‘Mastication rage’: A review of misophonia—An under-recognised symptom of psychiatric relevance? Australas. Psychiatry Bull. R. Aust. N. Z. Coll. Psychiatr. 2016, 24, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfanian, M.; Kartsonaki, C.; Keshavarz, A. Misophonia and comorbid psychiatric symptoms: A preliminary study of clinical findings. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2019, 73, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepsiak, M.A.; Sobczak, M.; Bohaterewicz, B.; Cichocki., Ł.; Dragan, Ł. Prevalence of Misophonia and Correlates of Its Symptoms among Inpatients with Depression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, S.S.; Alresheed, F.; Tu, J.C. Behavioral Treatment of Problem Behavior for an Adult with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Misophonia. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2020, 6, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiese-Himmel, C. Misophonie. Rubrik “Für Sie gelesen, für Sie gehört”. Stimme Sprache Gehör. 2020, 44, 126–127. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, M.Z.; Altimus, C.; Campbell, J. Research Topic ‘Advances in Understanding the Nature and Features of Misophonia’. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/25714/advances-in-understanding-the-nature-and-features-of-misophonia (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Savard, M.A.; Sares, A.G.; Coffey, E.B.; Deroche, M.L. Specificity of Affective Responses in Misophonia Depends on Trigger Identification. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=.+Specificity+of+affective+responses+in+misophonia+depends+on+trigger+identification.+&btnG= (accessed on 21 April 2022).

| Disorder | Similarities with Misophonia | Differences with Misophonia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric disorder | Specific phobia | A triggering stimulus may evoke a negative response, as well as avoidance behaviors. | In specific phobia, one experiences mostly anxiety and fear, whereas with misophonia a high degree of anger and aggression is perceived [20]. |

| Phonophobia | Fear of a specific sound. | The main symptom is not anxiety or fear as in phonophobia, but the feeling of irritation, disgust, or anger [10,20]. | |

| Social phobia | Habitual avoidance of social situations, due to experiencing anxiety and stress. | In social phobia, the reason is a hypersensitivity towards negative social evaluation; whereas in misophonia, the social situation is avoided to prevent an encounter with the misophonic sound [20]. | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | Aversive reaction to a stimulus and avoidance behaviors are shared. | The person with PTSD had to experience a traumatic event. In the case of misophonia, no such association has been demonstrated [20,35]. | |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) | They share an excessive preoccupation towards a specific stimulus, as well as the feeling of anxiety. | People with OCD often perform compulsive behaviors to reduce anxiety. In their case, there are no behaviors such as aggression and anger that may occur in misophonia. | |

| Intermittent explosive disorder | Here, the shared factor is anger. | In misophonia, the triggering stimulus of anger is always a sound, for explosive disorder it can be any stimulus. Loss of control does not usually occur in misophonia [20]. | |

| Eating behavior disorders | The most frequent emotional trigger in misophonia, as in the TCA, is food. | For the person with misophonia, the trigger is the sound of food, for ED, it is the ingestion of food [23]. | |

| Obsessive compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) | The shared factors are anger or aggression. | People with misophonia respond to the same auditory stimulus, people with OCPD do not relate to triggering sounds [20]. | |

| Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) | Auditory hyper-reactivity is observed. | People with ASD show intolerance to unexpected and loud noises. People with misophonia can react to any type of auditory stimulus [20]. | |

| Sensory processing disorder (SPD) | Auditory hyper-reactivity is observed. | The person with TPS reacts to unexpected and loud noises, there is also hyper-reactivity to other stimuli. The person with misophonia reacts to any auditory stimulus [20]. | |

| Personality disorders with impulsive aggression | Difficulty in controlling anger and impulsivity occurs. | The reactions are not necessarily related to a specific sound, as is the case with misophonia [55]. | |

| Auditive disorder | Tinnitus | Can provoke negative emotions; anxiety. | It is perceived in one or both ears in the absence of acoustic source [9]. |

| Hyperacusis | Negative reaction to any auditory stimulus with physical characteristics (loudness and frequency) [55]. | The stimulus characteristics are neutral or of very low frequency and intensity and context-independent [3,56]. | |

| Self-Administered Scales for Misophonia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Description | Aim | Comment |

| Misophonia Activation Scale (MAS-1) [76] | Developed by Fitzmaurice (Misophonia-uk-org) | To evaluate the severity of misophonia on a scale of 1 to 10 where extreme 10 indicates the most severe level of misophonic reaction. | It has been used in different studies, but has not been validated. [35,53,77] |

| Amsterdam Misophonia Scale (A-MISO-S) [20] | It is adapted from a scale for measuring obsessive-compulsive disorder (Yale-Brown Scale). | To measure the intensity of misophonia and its influence on social functioning, anger, and efforts to inhibit aggressive impulses. | Designed from another scale that measures another symptomatology. |

| Misophonia Questionnaire (MQ) [1] | It is composed of the symptom scale, the emotions and behaviors scale, and the severity scale. | To assess the sensitivity to sounds, explores the emotional and behavioral reaction associated with the stimulus. | Widely used [31,57,78,79]. |

| Misophonia Physical Response Scale (MPRS) [80] | Developed by The Misophonia Treatment Institute | To collect the physical sensations related to misophonia. | It assesses the intensity of the physiological response. |

| Online questionnaire [40] | Designed to know the frequency of misophonic people in the general population. | To inquire about the family history of misophonia, the presence of symptoms, and the characteristic of the response. | |

| Selective Sound Sensitivity Syndrome Scale (S-Five) [30] | For its development, a sample was used in the United Kingdom for people over 18 years of age. | To evaluate internalizing and externalizing appraisals, as well as threat perception and avoidance behavior. | Under development and in the process of validation. |

| MisoQuest [81] | Validated questionnaire based on diagnostic criteria proposed in other studies. | Rule out the consideration of violent behavior in response to misophonic triggers as a symptom of misophonia. | The reliability of this questionnaire was shown to be excellent. |

| Misophonia Response Scale (MRS) [82] | This scale was not conducted as a specific tool to diagnose the presence of misophonia. | To know the magnitude of the misophonic response in the presence of innocuous stimuli. Auditory, olfactory, visual, and tactile stimuli are also assessed. | Adequate discriminant and convergent validity. Good internal consistency. |

| Duke Misophonia Questionnaire (DMQ) [83] | Scale of 86 items: subdivided into (a) general severity of symptoms and (b) coping. | Development and psychometric validation of a self-report measure of misophonia. | The subscales can be used individually. |

| Misophonia Emotion Responses (MER-2) [35] | At the time of the present study, these measures had not yet been subjected to psychometric evaluation. | ||

| Misophonia Coping Responses Scale (MCRS) [35] | |||

| Misophonia Trigger Severity Scale [35]. | |||

| Sussex Misophonia Scale for Adolescents (SMS-Adolescent) [84] | The first questionnaire of misophonia validated for children and adolescents (10 to 14 years old). | It is an adapted version of the scale for adults [85]. | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferrer-Torres, A.; Giménez-Llort, L. Misophonia: A Systematic Review of Current and Future Trends in This Emerging Clinical Field. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6790. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116790

Ferrer-Torres A, Giménez-Llort L. Misophonia: A Systematic Review of Current and Future Trends in This Emerging Clinical Field. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6790. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116790

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerrer-Torres, Antonia, and Lydia Giménez-Llort. 2022. "Misophonia: A Systematic Review of Current and Future Trends in This Emerging Clinical Field" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6790. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116790

APA StyleFerrer-Torres, A., & Giménez-Llort, L. (2022). Misophonia: A Systematic Review of Current and Future Trends in This Emerging Clinical Field. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6790. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116790