Stunting Status of Ever-Married Adolescent Mothers and Its Association with Childhood Stunting with a Comparison by Geographical Region in Bangladesh

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Variables under Study

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

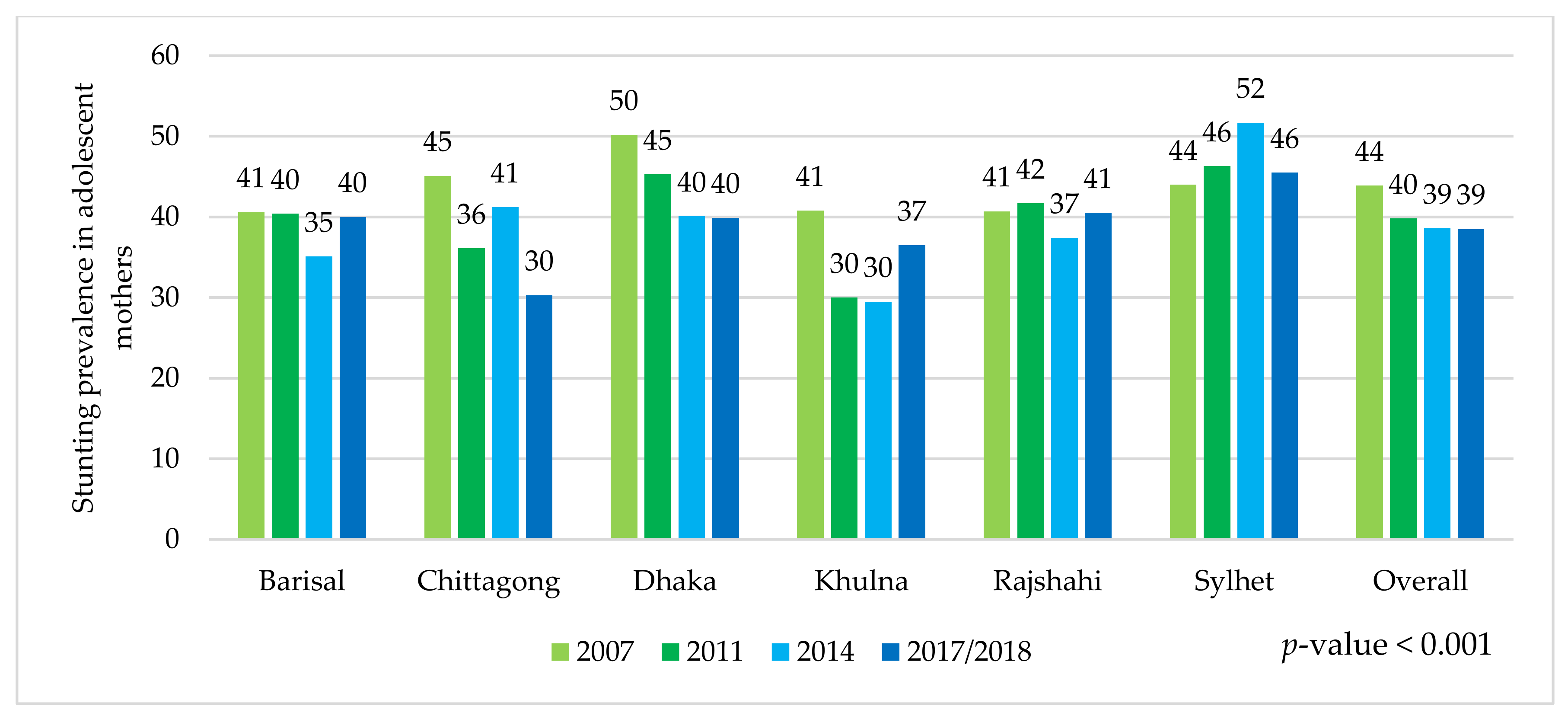

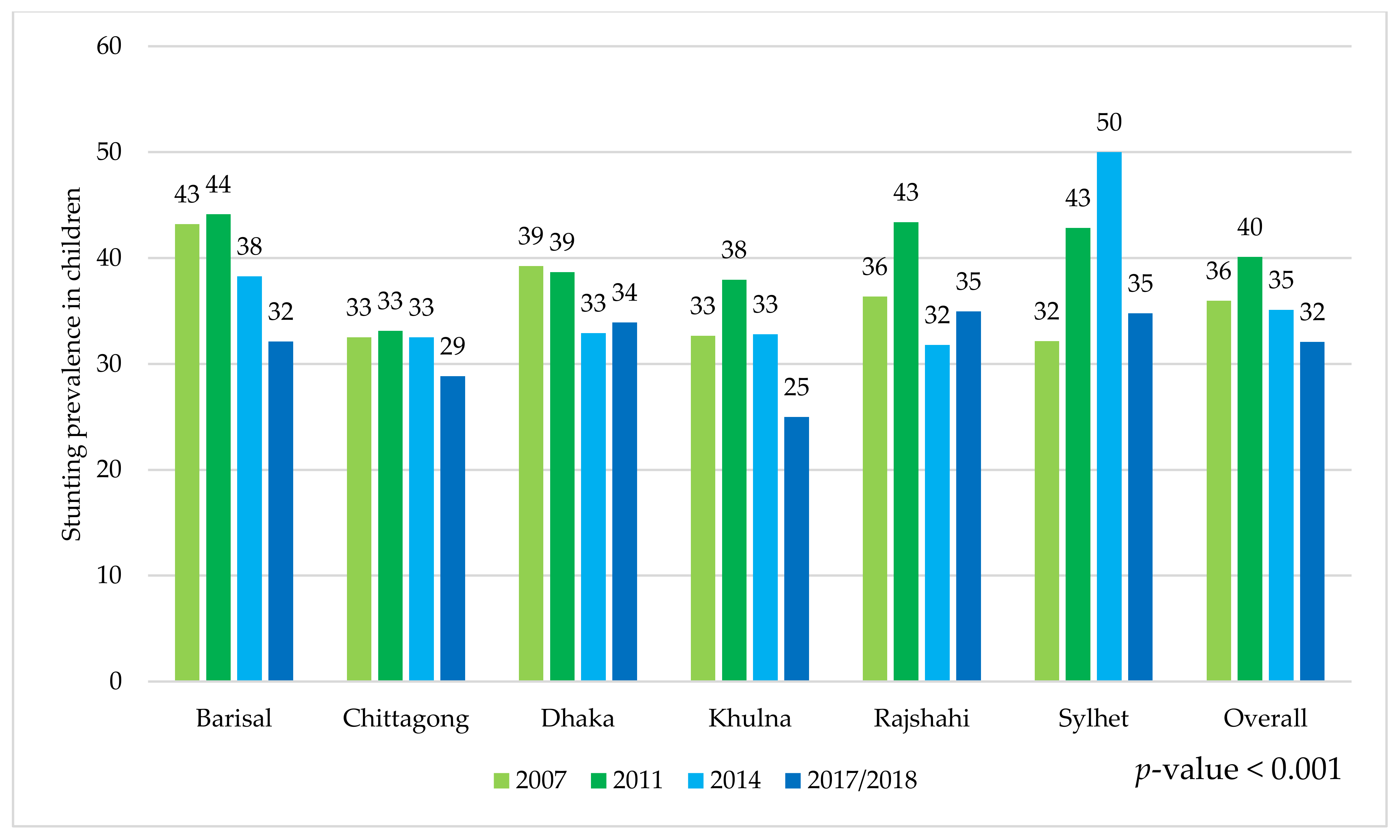

3.2. Prevalence of Stunting

3.3. Factors Associated with Adolescent Stunting

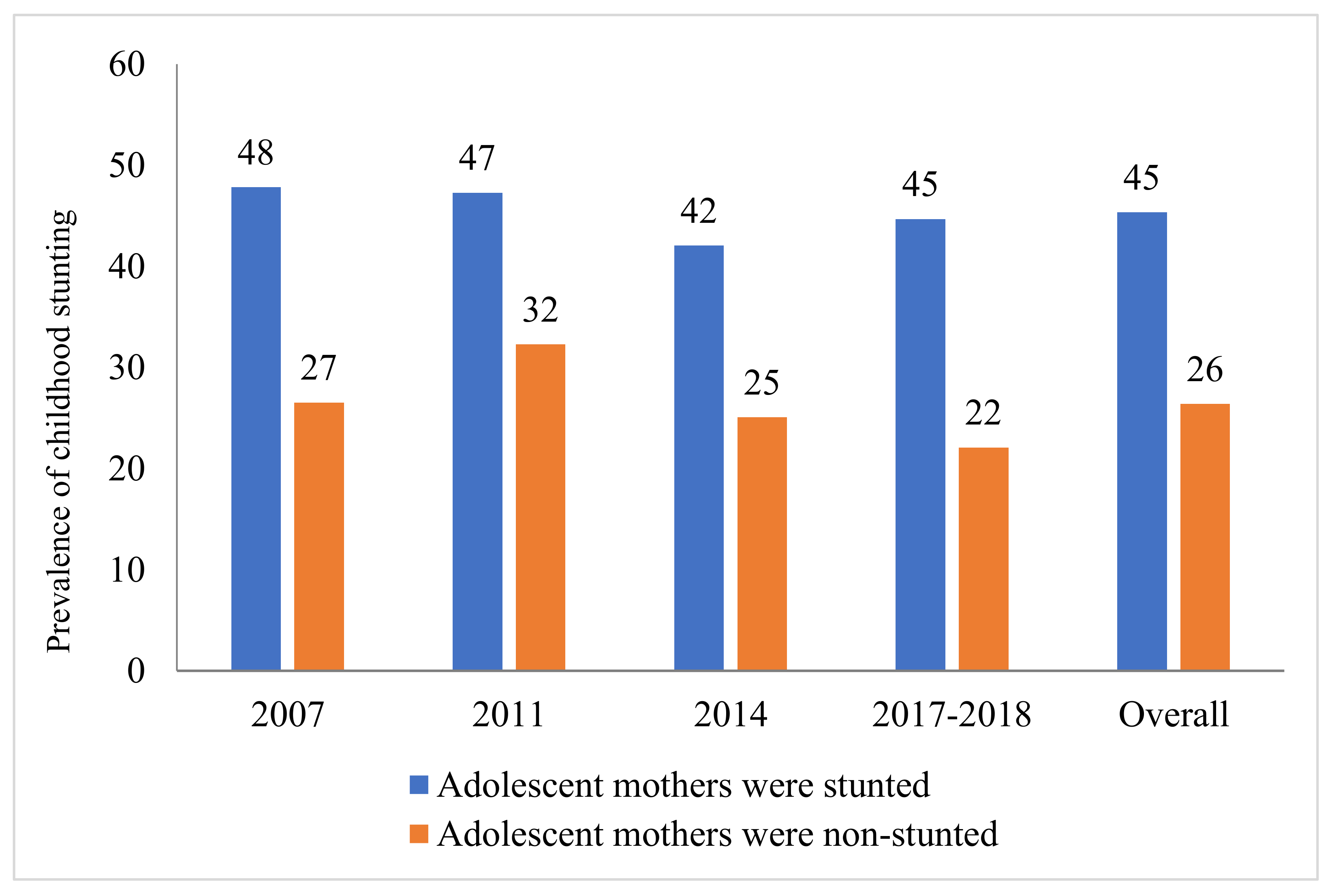

3.4. Association between Maternal and Childhood Stunting

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). State of World Population 2005: The Promise of Equality Gender Equity, Reproductive Health and the Millennium Development Goals; United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA): New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, K.; Malek, M.A.; Faruque, A.S.G.; Salam, M.A.; Ahmed, T. Health and nutritional status of children of adolescent mothers: Experience from a diarrhoeal disease hospital in Bangladesh. Acta Paediatr. 2007, 96, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Scott, S.; Neupane, S.; Tran, L.M.; Menon, P. Social, biological, and programmatic factors linking adolescent pregnancy and early childhood undernutrition: A path analysis of India’s 2016 National Family and Health Survey. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2019, 3, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, P.; Scott, S.; Khuong, L.; Pramanik, P.; Ahmed, A.; Afsana, K.; Menon, P. Why Are Adolescent Mothers More iikely to Have Stunted and Underweight Children Than Adult Mothers? A Path Analysis Using Data from 30,000 Bangladeshi Mothers, 1996–2014. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, K.; Christodoulou, J.; Stansert-Katzen, L.; Dippenaar, E.; Laurenzi, C.; le Roux, I.M.; Tomlinson, M.; Rotheram-Borus, M.J. A longitudinal cohort study of rural adolescent vs adult South African mothers and their children from birth to 24 months. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santosa, A.; Novanda Arif, E.; Abdul Ghoni, D. Effect of maternal and child factors on stunting: Partial least squares structural equation modeling. Clin. Exp. Pediatrics 2022, 65, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisai, S. Maternal height as an independent risk factor for neonatal size among adolescent bengalees in kolkata, India. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2010, 20, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Amare, Z.Y.; Ahmed, M.E.; Mehari, A.B. Determinants of nutritional status among children under age 5 in Ethiopia: Further analysis of the 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey. Glob. Health 2019, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beal, T.; Tumilowicz, A.; Sutrisna, A.; Izwardy, D.; Neufeld, L.M. A review of child stunting determinants in Indonesia. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Zaheer, S.; Safdar, N.F. Determinants of stunting, underweight and wasting among children children < 5 years of age: Evidence from 2012-2013 Pakistan demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT). ICF. In Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017–2018; NIPORT: Dhaka, Bangladesh; ICF: Rockville, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Onis, M.d.; Onyango, A.W.; Borghi, E.; Siyam, A.; Nishida, C.; Siekmann, J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, M.A.; Platts-Mills, J.A.; Mduma, E.; Bodhidatta, L.; Bessong, P.; Shakoor, S.; Kang, G.; Kosek, M.N.; Lima, A.A.M.; Shrestha, S.K.; et al. Determinants of Campylobacter infection and association with growth and enteric inflammation in children under 2 years of age in low-resource settings. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onis, M.d.; Bloessner, M. WHO Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Assefa, H.; Belachew, T.; Negash, L. Socio-demographic factors associated with underweight and stunting among adolescents in Ethiopia. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2015, 20, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senbanjo, I.O.; Oshikoya, K.A.; Odusanya, O.O.; Njokanma, O.F. Prevalence of and risk factors for stunting among school children and adolescents in Abeokuta, southwest Nigeria. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2011, 29, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudel, R.; Pradhan, B.; Wagle, R.R.; Pahari, D.P.; Onta, S.R. Risk factors for stunting among children: A community based case control study in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. (KUMJ) 2012, 10, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Akram, R.; Sultana, M.; Ali, N.; Sheikh, N.; Sarker, A.R. Prevalence and Determinants of Stunting Among Preschool Children and Its Urban-Rural Disparities in Bangladesh. Food Nutr. Bull. 2018, 39, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, P.; Ruel, M.T.; Morris, S.S. Socio-economic differentials in child stunting are consistently larger in urban than in rural areas. Food Nutr. Bull. 2000, 21, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saha, U.R.; Chattapadhayay, A.; Richardus, J.H. Trends, prevalence and determinants of childhood chronic undernutrition in regional divisions of Bangladesh: Evidence from demographic health surveys, 2011 and 2014. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Akombi, B.J.; Agho, K.E.; Hall, J.J.; Merom, D.; Astell-Burt, T.; Renzaho, A.M.N. Stunting and severe stunting among children under-5 years in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chirande, L.; Charwe, D.; Mbwana, H.; Victor, R.; Kimboka, S.; Issaka, A.I.; Baines, S.K.; Dibley, M.J.; Agho, K.E. Determinants of stunting and severe stunting among under-fives in Tanzania: Evidence from the 2010 cross-sectional household survey. BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khanal, V.; Sauer, K.; Zhao, Y. Exclusive breastfeeding practices in relation to social and health determinants: A comparison of the 2006 and 2011 Nepal Demographic and Health Surveys. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Indicators, % (n) | BDHS Round | |||

| 2007 | 2011 | 2014 | 2017–2018 | |

| Household characteristics | N = 1348 | N = 2004 | N = 2023 | N = 1951 |

| Geographical area | ||||

| Barisal | 13.0 (175) | 12.3 (247) | 13.8 (279) | 11.4 (222) |

| Chittagong | 18.3 (247) | 15.6 (313) | 17.6 (356) | 15.7 (307) |

| Dhaka ! | 21.1 (284) | 17.8 (356) | 16.8 (339) | 26.9 (525) |

| Khulna | 15.5 (209) | 15.7 (315) | 13.6 (276) | 13.3 (259) |

| Rajshahi $ | 20.7 (279) | 30.5 (611) | 27.9 (565) | 25.1 (490) |

| Sylhet | 11.4 (154) | 8.1 (162) | 10.3 (208) | 7.6 (148) |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Urban | 30.4 (410) | 30.5 (611) | 31.1 (629) | 31.4 (612) |

| Rural | 69.6 (938) | 69.5 (1393) | 68.9 (1394) | 68.6 (1339) |

| Wealth index | ||||

| Poorest | 14.3 (193) | 16.9 (338) | 19.3 (391) | 21.2 (413) |

| Poorer | 21.7 (293) | 24 (481) | 20.5 (415) | 22.4 (437) |

| Middle | 22.6 (305) | 22.2 (445) | 22.6 (457) | 21 (409) |

| Richer | 21.2 (286) | 22.2 (444) | 22.6 (458) | 20.7 (403) |

| Richest | 20.1 (271) | 14.8 (296) | 14.9 (302) | 14.8 (289) |

| Number of HH members 1 | 6.1 (3.3) | 5.9 (2.9) | 5.8 (2.8) | 5.9 (2.7) |

| Improved toilet | 35.1 (458) | 45.7 (893) | 59.4 (1185) | 52.5 (976) |

| Source of drinking water | 79 (1064) | 81 (1623) | 81 (1636) | 77.3 (1499) |

| Religion | ||||

| Other | 7.2 (97) | 8.8 (177) | 7.3 (147) | 6.0 (116) |

| Muslim | 92.8 (1251) | 91.2 (1827) | 92.7 (1876) | 94.1 (1835) |

| Ever-married adolescent girls’ characteristics | N = 1328 | N = 1961 | N = 2006 | N = 1917 |

| Height (cm) 1 | 150.4 (6.2) | 150.9 (5.4) | 151.2 (5.6) | 151.3 (5.3) |

| Weight (kg) 1 | 44.9 (7.4) | 45.3 (7.3) | 46.5 (8) | 48 (8.2) |

| Age (years) 1 | 18 (1.3) | 17.9 (1.5) | 18 (1.3) | 18.2 (1.2) |

| Height-for-age z-score 1 | 1.9 (0.9) | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.8) |

| BMI-for-age z-score 1 | 0.5 (2.6) | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.4 (1) | 0.2 (1.1) |

| Stunting | 43.9 (583) | 39.8 (781) | 38.6 (774) | 38.5 (739) |

| Maternal education | ||||

| No education | 10.7 (144) | 7.2 (145) | 5.2 (105) | 2.3 (45) |

| Primary | 28.4 (383) | 27.4 (550) | 25.6 (517) | 22.2 (434) |

| Secondary | 57.8 (779) | 58.5 (1172) | 59.7 (1208) | 61 (1191) |

| Higher | 3.1 (42) | 6.8 (137) | 9.5 (193) | 14.4 (281) |

| Husband’s education | ||||

| No education | 24 (323) | 16.7 (334) | 13.9 (282) | 11 (214) |

| Primary | 34.5 (465) | 33.7 (676) | 33.1 (669) | 34.4 (672) |

| Secondary | 31.8 (429) | 39.7 (795) | 40.8 (825) | 37.5 (731) |

| Higher | 9.7 (131) | 9.9 (199) | 12.2 (247) | 17.1 (334) |

| Husband’s age 1 | 26.6 (6) | 26.2 (6.1) | 26 (4.7) | 25.9 (4.4) |

| Had the ability to take decisions herself (or jointly with her husband) | ||||

| i. Own health care | 37.5 (506) | 47.4 (925) | 45.8 (907) | 57.1 (1079) |

| ii. Major household purchases | 32 (432) | 39.2 (766) | 37.4 (741) | 43 (814) |

| iii. Visits to her family or relatives | 34.1 (459) | 43.7 (854) | 40.7 (806) | 49.5 (936) |

| All of the three decisions | 18 (242) | 28.8 (563) | 25.9 (513) | 32.7 (618) |

| Attitudes to domestic violence | 64.5 (870) | 67.2 (1346) | 70.2 (1421) | 80.5 (1570) |

| At least four ANC visits from a medically trained provider | 8.6 (116) | 11.4 (229) | 10.7 (216) | 20.1 (393) |

| Use of contraception | 39.2 (529) | 48.2 (966) | 50.3 (1017) | 48.9 (955) |

| Delivery type | ||||

| Caesarean section | 7.5 (56) | 12.4 (128) | 21 (197) | 28.9 (251) |

| Non-caesarean | 92.5 (693) | 87.6 (905) | 79 (742) | 71.1 (618) |

| Child’s characteristics | N = 753 | N = 1042 | N = 1061 | N = 987 |

| Child’s age (months)1 | 18.1 (13.5) | 17.6 (14.3) | 17.8 (13.7) | 17.9 (14.1) |

| Child’s sex | ||||

| Male | 49.8 (375) | 52.1 (543) | 51.0 (541) | 52.6 (519) |

| Female | 50.2 (378) | 47.9 (499) | 49.0 (520) | 47.4 (468) |

| Childhood stunting | 36.0 (240) | 40.1 (366) | 35.1 (332) | 32.1 (293) |

| Indicators | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographical area | |||||

| Sylhet | Reference | Reference | |||

| Barisal | 0.69 (0.55, 0.87) | 0.002 | 0.76 (0.60, 0.98) | 0.032 | |

| Chittagong | 0.64 (0.52, 0.80) | <0.001 | 0.78 (0.62, 0.98) | 0.031 | |

| Dhaka ! | 0.84 (0.67, 1.04) | 0.108 | 0.92 (0.73, 1.17) | 0.508 | |

| Khulna | 0.54 (0.43, 0.68) | <0.001 | 0.61 (0.48, 0.78) | <0.001 | |

| Rajshahi $ | 0.75 (0.61, 0.92) | 0.006 | 0.78 (0.62, 0.97) | 0.028 | |

| Place of residence | |||||

| Rural | Reference | Reference | |||

| Urban | 1.08 (0.96, 1.23) | 0.203 | 1.24 (1.08, 1.43) | 0.003 | |

| Wealth index | |||||

| Richest | Reference | Reference | |||

| Poorest | 1.75 (1.43, 2.13) | <0.001 | 1.65 (1.30, 2.10) | <0.001 | |

| Poorer | 1.62 (1.35, 1.94) | <0.001 | 1.64 (1.33, 2.04) | <0.001 | |

| Middle | 1.23 (1.02, 1.49) | 0.028 | 1.39 (1.13, 1.71) | 0.002 | |

| Richer | 1.22 (1.01, 1.47) | 0.036 | 1.32 (1.09, 1.60) | 0.005 | |

| Education | |||||

| At least secondary | Reference | Reference | |||

| Below secondary | 1.68 (1.49, 1.89) | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.14, 1.51) | <0.001 | |

| Age (months) | 1.01 (1.01, 1.01) | <0.001 | 1.01 (1.01, 1.02) | <0.001 | |

| Working status | |||||

| Not working | Reference | Reference | |||

| Working | 1.29 (1.12, 1.50) | 0.001 | 1.17 (0.99, 1.38) | 0.058 | |

| Husband’s age | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) | <0.001 | |

| Husband’s education | |||||

| At least secondary | Reference | Reference | |||

| Below secondary | 1.59 (1.42, 1.78) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.10, 1.42) | 0.001 | |

| Domestic violence | |||||

| No | Reference | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.05 (0.93, 1.19) | 0.411 | 1.16 (1.02, 1.32) | 0.027 | |

| Religion | |||||

| Other | Reference | Reference | |||

| Muslim | 1.31 (1.07, 1.60) | 0.010 | 1.36 (1.10, 1.68) | 0.005 | |

| Round | |||||

| 2007 | Reference | Reference | |||

| 2011 | 0.86 (0.73, 1.01) | 0.065 | 0.88 (0.74, 1.04) | 0.128 | |

| 2014 | 0.79 (0.66, 0.93) | 0.006 | 0.79 (0.66, 0.94) | 0.007 | |

| 2017–2018 | 0.75 (0.64, 0.88) | 0.001 | 0.73 (0.62, 0.87) | <0.001 | |

| BDHS Round | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted * OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2.54 (1.75, 3.69) | <0.001 | 2.62 (1.74, 3.92) | <0.001 |

| 2011 | 1.88 (1.39, 2.55) | <0.001 | 1.66 (1.19, 2.32) | 0.003 |

| 2014 | 2.17 (1.52, 3.10) | <0.001 | 2.36 (1.58, 3.53) | <0.001 |

| 2017–2018 | 2.85 (2.07, 3.91) | <0.001 | 3.78 (2.59, 5.53) | <0.001 |

| Overall | 2.31 (1.95, 2.73) | <0.001 | 2.36 (1.96, 2.84) | <0.001 |

| Indicators | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p | Adjusted * OR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction of adolescent mother’s stunting and geographical area | ||||

| Stunted mother × Sylhet | Reference | Reference | ||

| Stunted mother × Barisal | 1.39 (0.86, 2.25) | 0.173 | 1.13 (0.69, 1.84) | 0.632 |

| Stunted mother × Chittagong | 0.76 (0.49, 1.20) | 0.239 | 0.83 (0.52, 1.32) | 0.435 |

| Stunted mother × Dhaka ! | 0.93 (0.60, 1.45) | 0.742 | 0.89 (0.56, 1.42) | 0.624 |

| Stunted mother × Khulna | 1.05 (0.64, 1.71) | 0.847 | 1.03 (0.62, 1.73) | 0.900 |

| Stunted mother × Rajshahi $ | 1.16 (0.76, 1.76) | 0.491 | 0.92 (0.60, 1.43) | 0.725 |

| Non-stunted mother × Barisal | 0.51 (0.32, 0.81) | 0.004 | 0.43 (0.26, 0.70) | 0.001 |

| Non-stunted mother × Chittagong | 0.37 (0.24, 0.57) | <0.001 | 0.37 (0.23, 0.60) | <0.001 |

| Non-stunted mother × Dhaka ! | 0.44 (0.28, 0.68) | <0.001 | 0.37 (0.23, 0.59) | <0.001 |

| Non-stunted mother × Khulna | 0.35 (0.22, 0.55) | <0.001 | 0.32 (0.20, 0.52) | <0.001 |

| Non-stunted mother × Rajshahi $ | 0.45 (0.29, 0.68) | <0.001 | 0.39 (0.25, 0.60) | <0.001 |

| Non-stunted mother × Sylhet | 0.73 (0.43, 1.24) | 0.245 | 0.83 (0.47, 1.45) | 0.509 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haque, M.A.; Wahid, B.Z.; Tariqujjaman, M.; Khanam, M.; Farzana, F.D.; Ali, M.; Naz, F.; Sanin, K.I.; Faruque, A.; Ahmed, T. Stunting Status of Ever-Married Adolescent Mothers and Its Association with Childhood Stunting with a Comparison by Geographical Region in Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116748

Haque MA, Wahid BZ, Tariqujjaman M, Khanam M, Farzana FD, Ali M, Naz F, Sanin KI, Faruque A, Ahmed T. Stunting Status of Ever-Married Adolescent Mothers and Its Association with Childhood Stunting with a Comparison by Geographical Region in Bangladesh. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116748

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaque, Md. Ahshanul, Barbie Zaman Wahid, Md. Tariqujjaman, Mansura Khanam, Fahmida Dil Farzana, Mohammad Ali, Farina Naz, Kazi Istiaque Sanin, ASG Faruque, and Tahmeed Ahmed. 2022. "Stunting Status of Ever-Married Adolescent Mothers and Its Association with Childhood Stunting with a Comparison by Geographical Region in Bangladesh" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116748

APA StyleHaque, M. A., Wahid, B. Z., Tariqujjaman, M., Khanam, M., Farzana, F. D., Ali, M., Naz, F., Sanin, K. I., Faruque, A., & Ahmed, T. (2022). Stunting Status of Ever-Married Adolescent Mothers and Its Association with Childhood Stunting with a Comparison by Geographical Region in Bangladesh. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116748