Understanding the Influence of Community-Level Determinants on Children’s Social and Emotional Well-Being: A Systems Science and Participatory Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

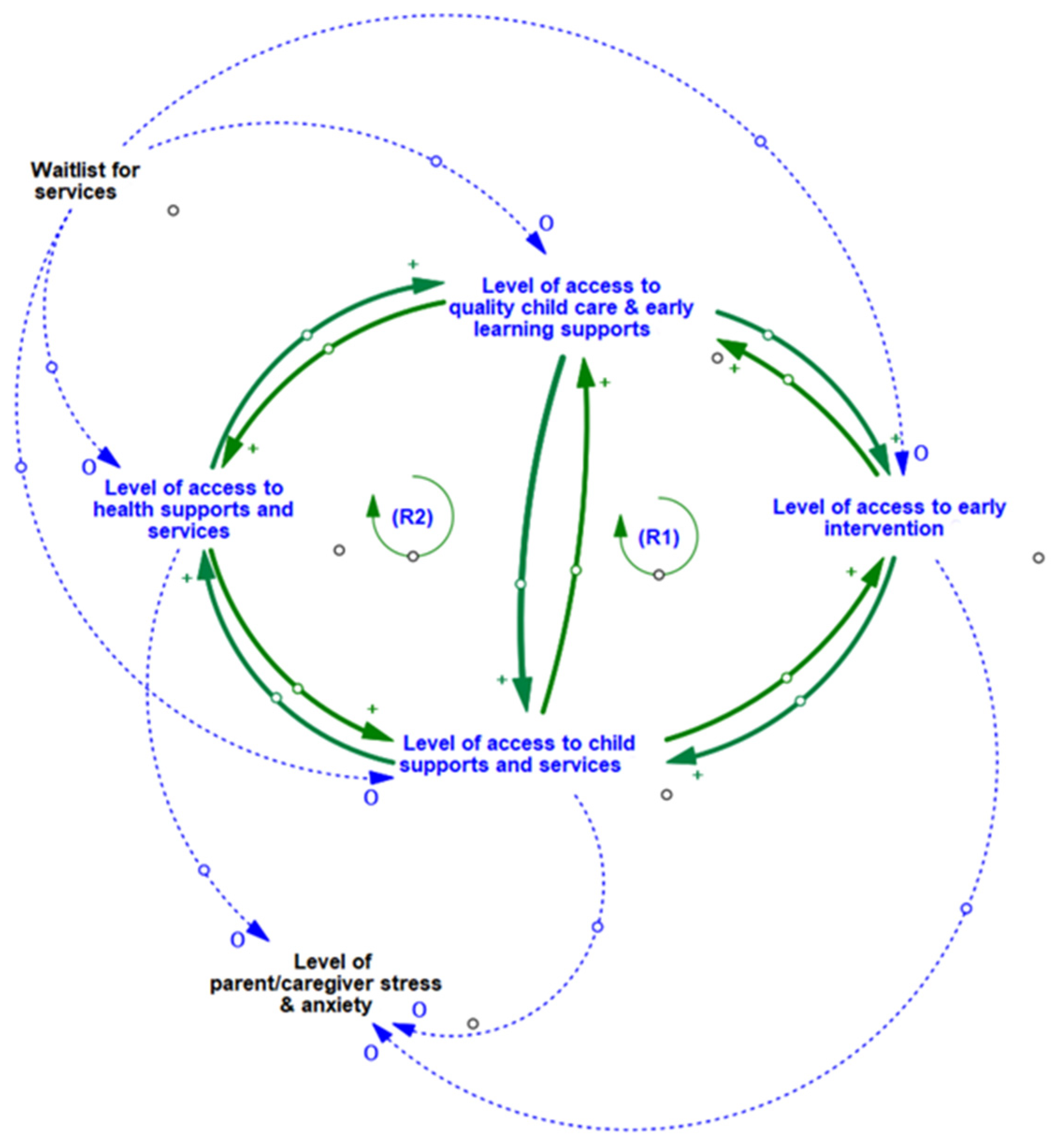

3.1. Enabling Multiple Access Points to a Range of Interconnected Community Services and Programs

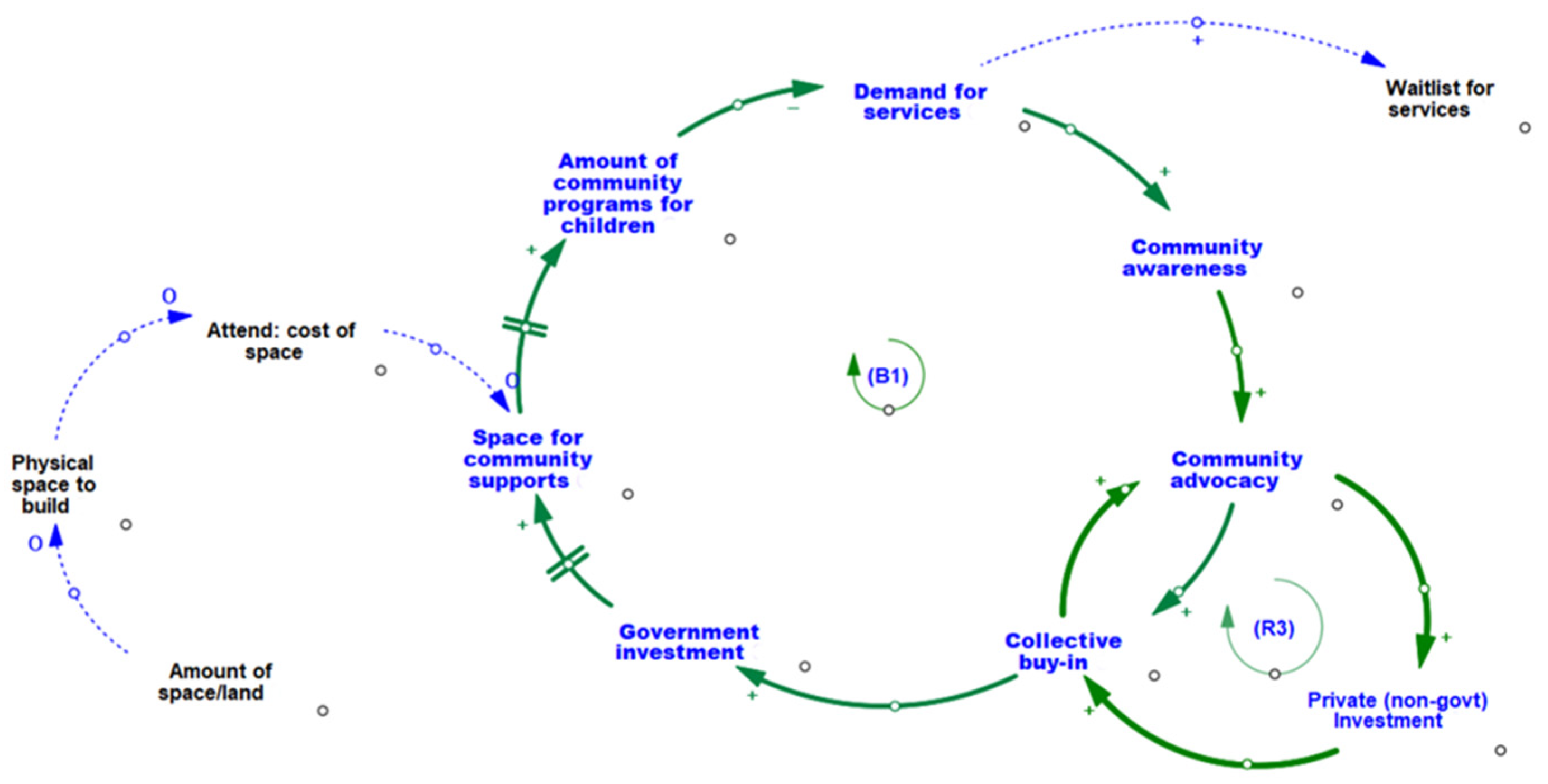

3.2. Increasing the Amount of Community Programming Available by Strengthening Levels of Collective Community Action and Ensuring the Availability of Necessary Physical Space and Infrastructure

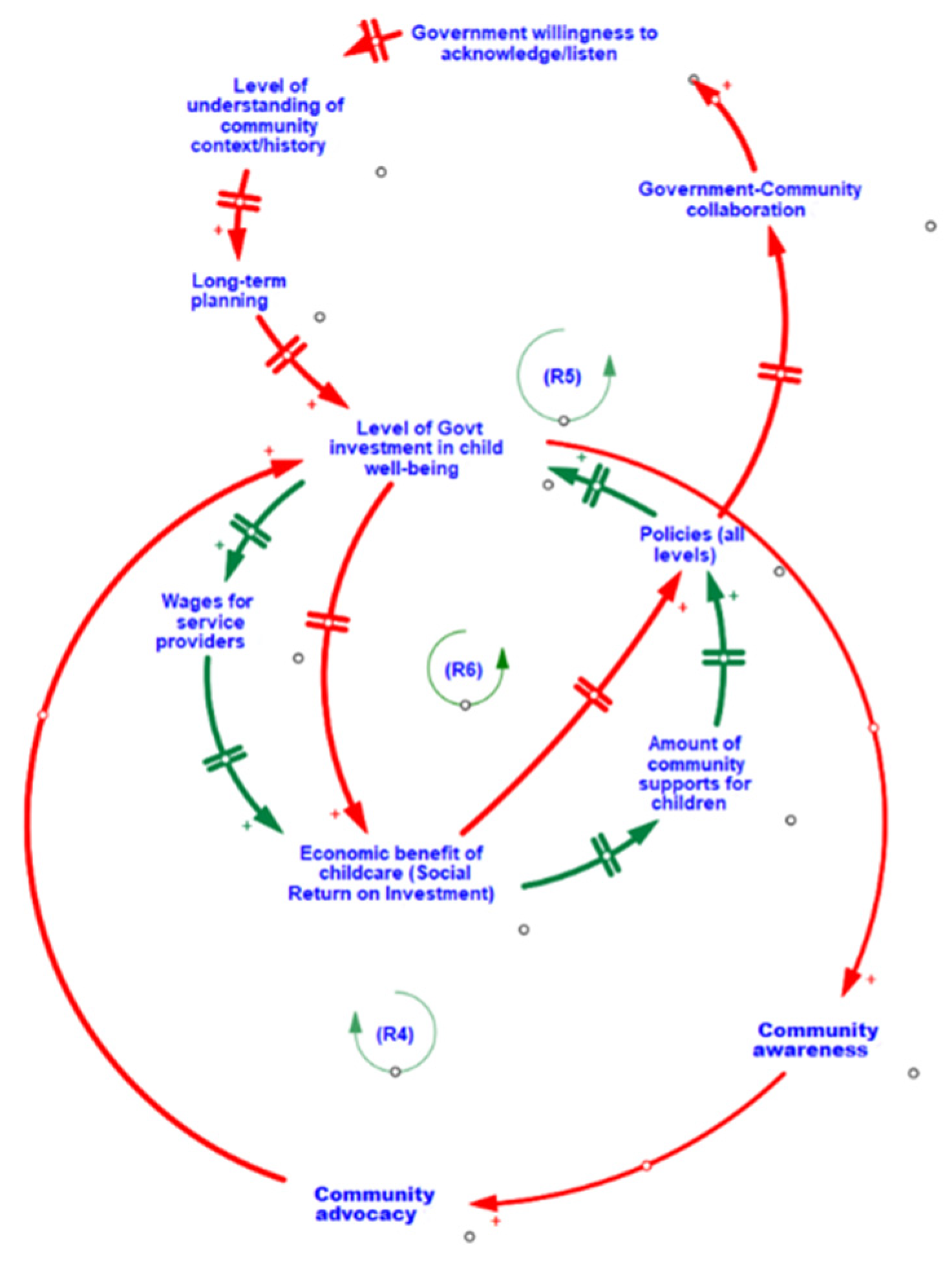

3.3. Foster Longer-Term Societal Returns on Investment and Community Advocacy through Improving Government Investment in Child Well-Being

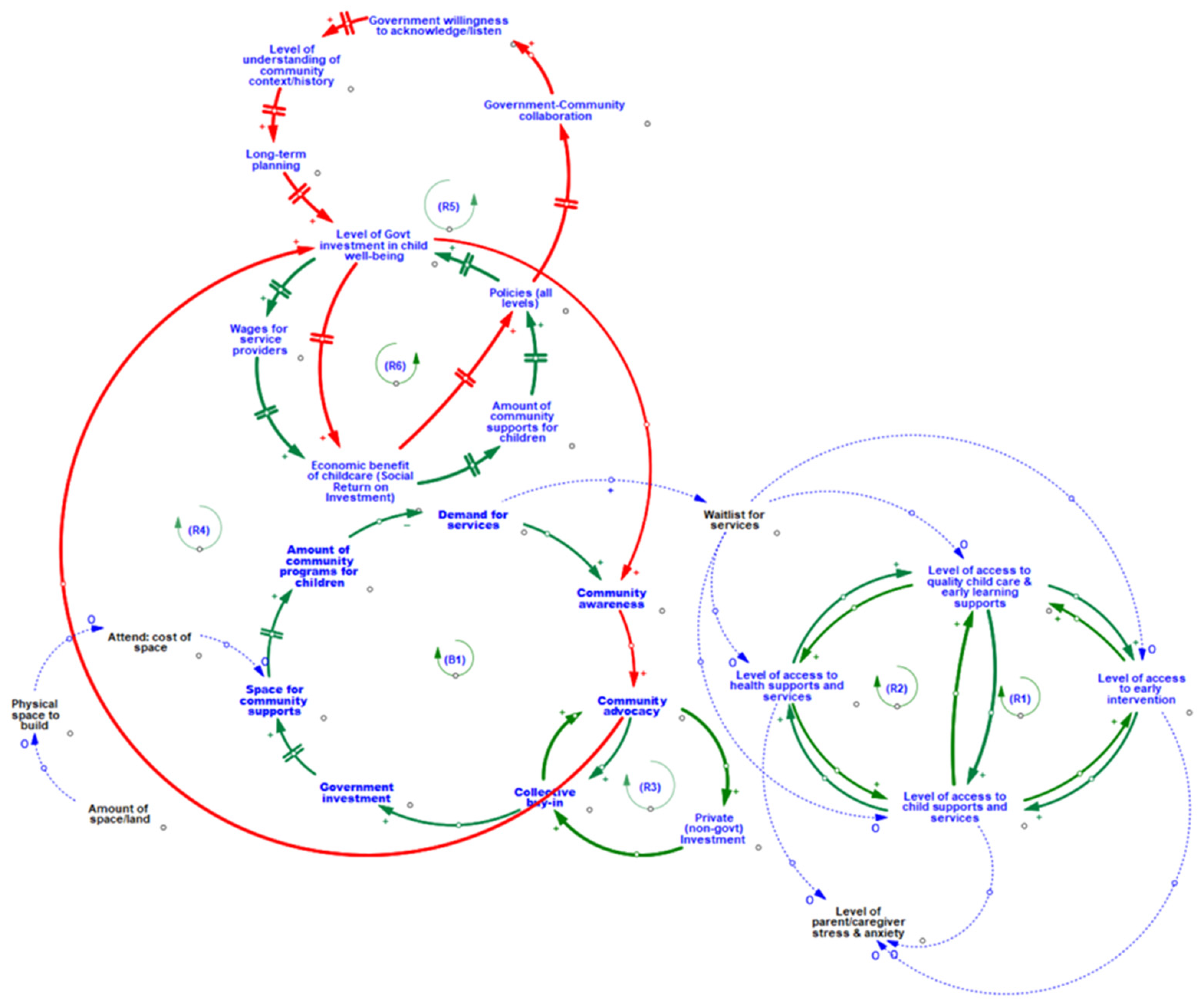

3.4. Bridging the Multiple Associations and Feedback Mechanisms within the Community Environment

4. Discussion

5. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freeman, J.G.; King, M.; Pickett, W.; Craig, W.; Elgar, F.; Janssen, I.; Klinger, D. The Health of Canada’s Young People: A Mental Health Focus; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). The Human Face of Mental Health and Mental Illness in Canada, 2006; HP5-19/2006E; Public Health Agency of Canada, Mood Disorders Society of Canada, Health Canada, Statistics Canada, Canadian Institute for Health Information: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006. Available online: https://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/human-humain06/pdf/human_face_e.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- McMullen, K.; Gilmore, J. A Note on High School Graduation and School Attendance, by Age and Province, 2009/2010; Catalogue No. 81-004-X; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2010. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/81-004-x/2010004/article/11360-eng.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Fontaine, N.; Carbonneau, R.; Barker, E.D.; Vitaro, F.; Hébert, M.; Côté, S.M.; Nagin, D.S.; Zoccolillo, M.; Tremblay, R.E. Girls’ hyperactivity and physical aggression during childhood and adjustment problems in early adulthood: A 15-year longitudinal study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 65, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Human Early Learning Partnership (HELP); EDI. Early Years Development Instrument; British Columbia Provincial Report; University of British Columbia, School of Population and Public Health: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2016; Available online: http://earlylearning.ubc.ca/media/edibc2016provincialreport.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Maloney, J.; Rowcliffe, P.; Sauve, J.; Wallace, C.; Adam, S. Environmental Scan of Social and Emotional Development Programs for the Early Years in British Columbia. Human Early Learning Partnership; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2017; Unpublished report (Not available online). [Google Scholar]

- Davis, E.L.; Levine, L.J. Emotion regulation strategies that promote learning: Reappraisal enhances children’s memory for educational information. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, N.; Sadovsky, A.; Spinrad, T.L. Associations of emotion-related regulation with language skills, emotion knowledge, and academic outcomes. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2005, 109, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, J.A.; Levine, L.J.; Pizarro, D.A. ‘Just stop thinking about it’: Effects of emotional disengagement on children’s memory for educational material. Emotion 2007, 7, 812–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- BC Stats. Socio-Economic Profiles. 2012. Available online: http://www.bcstats.gov.bc.ca/StatisticsBySubject/SocialStatistics/SocioEconomicProfilesIndices/Profiles.aspx (accessed on 6 August 2012).

- Krieger, N. Proximal, Distal, and the Politics of Causation: What’s Level Got to Do with It? Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons-Ruth, K.; Manly, J.; Von Klitzing, K.; Tamminen, T.; Emde, R.; Fitzgerald, H.; Paul, C.; Keren, M.; Berg, A.; Foley, M.; et al. The Worldwide Burden of Infant Mental and Emotional Disorder: Report of the Task Force of the World Association for Infant Mental Health. Infant Ment. Health J. 2017, 38, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gehlert, S.; Sohmer, D.; Sacks, T.; Mininger, C.; McClintock, M.; Olopade, O. Targeting Health Disparities: A Model Linking Upstream Determinants to Downstream Interventions. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomlinson, M. Infant Mental Health in the Next Decade: A Call for Action. Infant Ment. Health J. 2015, 36, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adamsons, K.; O’Brien, M.; Pasley, K. An Ecological Approach to Father Involvement in Biological and Stepfather Families. Fathering 2007, 5, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F.A.; Pungello, E.P.; Miller-Johnson, S. The Development of Perceived Scholastic Competence and Global Self-Worth in African American Adolescents from Low-Income Families: The Roles of Family Factors, Early Educational Intervention, and Academic Experience. J. Adolesc. Res. 2002, 17, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggins-Caspers, K.M.; Cadoret, R.J.; Knutson, J.F.; Langbehn, U. Biology-Environment Interaction and Evocative Biology-Environment Correlation: Contributions of Harsh Discipline and Parental Psychopathology to Problem Adolescent Behaviors. Behav. Genet. 2003, 33, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudge, J.R.; Odero, D.A.; Hogan, D.M.; Etz, K.E. Relations between the everyday activities of preschoolers and their teachers’ perceptions of their competence in the first years of school. Early Child. Res. Q. 2003, 18, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipuer, H.M. Dyadic attachments and community connectedness: Links with youths’ loneliness experiences. J. Community Psychol. 2001, 29, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criss, M.M.; Shaw, D.S.; Moilanen, K.L.; Hitchings, J.E.; Ingoldsby, E.M. Family, neighborhood, and peer characteristics as predictors of child adjustment: A longitudinal analysis of additive and mediation models. Soc. Dev. 2009, 18, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gest, S.D.; Rodkin, P.C. Teaching practices and elementary classroom peer ecologies. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 32, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford-Smith, M.E.; Brownell, C.A. Childhood peer relationships: Social acceptance, friendships, and peer networks. J. Sch. Psychol. 2003, 41, 235–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, E.; Allen, L.; Aber, J.L.; Mitchell, C.; Feinman, J.; Yoshikawa, H.; Comtois, K.A.; Golz, J.; Miller, R.L.; Ortiz-Torres, B.; et al. Development and validation of adolescent-perceived microsystem scales: Social support, daily hassles, and involvement. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 355–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P.; Dymnicki, A.B.; Taylor, R.D.; Schellinger, K.B. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, Z.N.; Mashburn, A.J. Family–school connectedness and children’s early social development. Soc. Dev. 2012, 21, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminen, T.; Puura, K. Infant/Early Years mental health. In Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, S.L.; Petrenko, C.L.M.; Gravener-Davis, J.A.; Handley, E.D. Advances in Prevention Science: A Developmental Psychopathology Perspective. In Developmental Psychopathology; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, T.; Tomlinson, M.; Tablante, E.; Britto, P.; Yousfzai, A.; Daelmans, B.; Darmstadt, G.L. Global research priorities to accelerate early child development in the sustainable development era. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e887–e889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allender, S.; Owen, B.; Kuhlberg, J.; Lowe, J.; Nagorcka-Smith, P.; Whelan, J.; Bell, C. A community based systems diagram of obesity causes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Homer, J.; Hirsch, G.; Minniti, M.; Pierson, M. Models for collaboration: How system dynamics helped a community organize cost-effective care for chronic illness. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2004, 20, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langellier, B.A.; Kuhlberg, J.A.; Ballard, E.A.; Slesinski, S.C.; Stankov, I.; Gouveia, N.; Meisel, J.D.; Kroker-Lobos, M.F.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Caiaffa, W.T.; et al. Using community-based system dynamics modeling to understand the complex systems that influence health in cities: The SALURBAL study. Health Place 2019, 60, 102215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovmand, P.S. Group Model Building and Community-Based System Dynamics Process. In Community Based System Dynamics; Hovmand, P.S., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovmand, P.S.; Andersen, D.F.; Rouwette, E.; Richardson, G.P.; Rux, K.; Calhoun, A. Group Model-Building ‘Scripts’ as a Collaborative Planning Tool. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2012, 29, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richardson, G.P. Problems in causal loop diagrams revisited. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 1997, 13, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L.K.; Sabounchi, N.S.; Kemner, A.L.; Hovmand, P. Systems Thinking in 49 Communities Related to Healthy Eating, Active Living, and Childhood Obesity. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2015, 21, S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, B.; Brown, A.D.; Kuhlberg, J.; Millar, L.; Nichols, M.; Economos, C.; Allender, S. Understanding a successful obesity prevention initiative in children under 5 from a systems perspective. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bureš, V. A Method for Simplification of Complex Group Causal Loop Diagrams Based on Endogenisation, Encapsulation and Order-Oriented Reduction. Systems 2017, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scriptapedia/Action Ideas—Wikibooks, Open Books for an Open World. 2019. Available online: https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Scriptapedia/Action_Ideas (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Minkler, M. Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. J. Urban Health 2005, 82 (Suppl. S2), ii3–ii12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B.; Oetzel, J.G.; Minkler, M. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity; John Wiley & Sons Incorporated: Newark, NJ, USA, 2017; Available online: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ubc/detail.action?docID=5097167 (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Watze, M.; Hallstedt, S.I. Profile model for management of sustainability integration in engineering design requirements. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, S.H. Social Capital and Community Development: An Analysis of Two Cases from India and Bangladesh. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2011, 46, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Social Capital, Civil Society and Development. Third World Q. 2001, 22, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. Active Social Capital: Tracing the Roots of Development and Democracy; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, S. Social Capital, Local Networks and Community Development. In Urban Livelihoods; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D.; Leonardi, R.; Nonetti, R.Y. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzmann, J.P.; McKnight, J. Building Communities from the Inside Out: A Path toward Finding and Mobilizing a Community’s Assets. Evanston, Ill: Center for Urban Affairs and Policy Research; Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Galston, W.A.; Baehler, K.J. Rural Development in the United States: Connecting Theory, Practice, and Possibilities; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbitt, K.; Jones, P.; Meegan, R. Tackling Social Exclusion: The Role of Social Capital in Urban Regeneration on Merseyside—From Mistrust to Trust? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2001, 9, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.S. Entrepreneurial Neighborhood Initiatives: Political Capital in Community Development. Econ. Dev. Q. 1999, 13, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M. Transformative Community Planning: Empowerment through Community Development. New Solut. 1997, 6, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biebel, K.; Geller, J.L. Challenges for a System of Care; Implementation Science and Practice Advances Research Center Publications: Worcester, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, B.; Kwon, J.; Swinburn, B.; Sacks, G. Swinburn, and G. Sacks. Understanding the dynamics of obesity prevention policy decision-making using a systems perspective: A case study of Healthy Together Victoria. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieder, E.; Larson, L.R.; Sas-Rolfes, M.; Kopainsky, B. Using Participatory System Dynamics Modeling to Address Complex Conservation Problems: Tiger Farming as a Case Study. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 2, 61. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fcosc.2021.696615 (accessed on 29 March 2022). [CrossRef]

| Number of Participants in Attendance (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECD Sector | GMB Session #1 | GMB Session #2 | GMB Session #3 | Total |

| (N = 17) | (N = 16) | (N = 13) | (N = 25) | |

| Childcare | 4 (23.5%) | 3 (18.8%) | 1 (7.7%) | 4 (16.0%) |

| Education | 3 (17.6%) | 3 (18.8%) | 4 (30.8%) | 4 (16.0%) |

| Service Delivery | 8 (47.1%) | 8 (50.0%) | 4 (30.8%) | 12 (48.0%) |

| Healthcare | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (6.3%) | 3 (23.1%) | 3 (12.0%) |

| Other | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (7.7%) | 1 (4.0%) |

| Loop | Loop Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| R5 | Shared Understanding and Priorities | When governments are willing to listen to communities, they are better able to understand the uniqueness and importance of a community’s history and context. This enables more tailored long-term planning and investments towards child well-being, which increases the social return on investment. Increasing returns encourage policies that continue to support child well-being, leading to greater collaborations between community and government, strengthening cross-sectorial relationships and reinforcing the willingness of governments to listen. |

| R6 | The Impact of Government Investments | When governments increase their investments in child development well-being, the wages for service providers are able to increase, which also increases social return on investment. Increasing social return promotes greater support from the community. Communities with plentiful support for child well-being often engage in community-led initiatives, including community-based research that help to support and guide policies aimed at further promoting child development and well-being. When policies move towards promoting child development and well-being, government investments follow, creating a reinforcing loop. |

| R4 | Community Advocacy and Government | High levels of community advocacy for child well-being can influence the level of funding received from governments. With increased funding, communities are able to implement new initiatives, which increase community awareness of the state of child vulnerability and importance of the early years. This reinforces the need and presence of community advocacy in support of children’s well-being. |

| B1 | Demand for Program and Services | When there is high demand for children’s programs/services, long waitlists can exist for families to access supports. Waitlists increase community awareness by being an indicator of unmet community need. With growing awareness comes greater community advocacy and buy-in in support of children and families. Collective buy-in increases the funding provided by local private businesses or organizations, which enable communities to allocate new spaces for programs services (located in built community infrastructure such as community centers), and subsequently expand on existing or create new programs/services for children and families. As more community-located supports become available, the demand and waitlists decrease. This balancing loop illustrates how the system can self-adjust to meet the needs of families with young children. |

| R3 | Advocacy within the Community | High levels of community advocacy for child well-being can influence the levels of private (non-government) funding. Support from private organizations such as local businesses and banks, contributes to increased awareness and collective buy-in from the community, furthering the level of community advocacy. |

| R1 | Impact of Multiple Access Points to Services/Supports | Access to one community service access point in the system begets access to additional services and supports. For example, when families with young children are able to acquire better access to health care in the community, their ability to access quality childcare and early learning supports improves, this in turn leads to greater access to early intervention which increases the level of child’s access to family supports, which feed back into improved access to health care. The inter-relationships in this loop are bi-directional. When families with young children are able to acquire better access to health care in the community their ability to access family supports is improved and this increases access to family supports and leads to increased levels of access to early intervention, which in turn enhances access to quality childcare and early learning supports, which contribute to improved access to health care. |

| R2 | Service Access via Connections to Information and Social Networks | When families with young children are able to access family supports (located in built community infrastructure such as community centers), they gain access to information from staff and other families, which may increase their awareness of other programs and services available within the community (e g., health care, quality daycare) that they may be eligible for. By engaging in these other programs services, families are able to connect with and receive additional family support, creating a reinforcing cycle whereby families continue to grow their knowledge and access opportunities. This creates a virtuous cycle where families who have access continue to gain more access. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poon, B.T.; Atchison, C.; Kwan, A. Understanding the Influence of Community-Level Determinants on Children’s Social and Emotional Well-Being: A Systems Science and Participatory Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105972

Poon BT, Atchison C, Kwan A. Understanding the Influence of Community-Level Determinants on Children’s Social and Emotional Well-Being: A Systems Science and Participatory Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):5972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105972

Chicago/Turabian StylePoon, Brenda T., Chris Atchison, and Amanda Kwan. 2022. "Understanding the Influence of Community-Level Determinants on Children’s Social and Emotional Well-Being: A Systems Science and Participatory Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 5972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105972

APA StylePoon, B. T., Atchison, C., & Kwan, A. (2022). Understanding the Influence of Community-Level Determinants on Children’s Social and Emotional Well-Being: A Systems Science and Participatory Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 5972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105972