Physical Activity for Children and Youth with Physical Disabilities: A Case Study on Implementation in the Municipality Setting

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Danish Political and Administrative Structure

1.2. Theoretical Framework: Policy Implementation and (Inter) Organisational Behaviour

1.2.1. Søren Winter’s Integrated Implementation Model

The Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Role in Policy Implementation

- Decrease demands for SLB performance by limiting information about services, which makes access difficult, and which imposes a variety of other psychological costs on the client;

- Ration services by giving higher priority to one type of service over others. This often occurs when other objectives are more clearly expressed (e.g., formalized academic goals compared to broadly worded ambitions) that are related to PA for all students in primary and lower secondary school;

- Standardise and routinise SLB work by dividing clients into categories instead of delivering individualised treatment or counselling.

Role of Management

1.2.2. Organisational and Interorganisational Behaviour

- (1)

- How do local policies support the implementation of PA for children and youth with physical disabilities?

- (2)

- How do Danish municipalities—at the organisational and interorganisational levels—work with for the implementation of PA possibilities for children and youth with physical disabilities?

- (3)

- How does the behaviour of municipal agents and the coordination across departments affect the performance in relation to ensuring PA possibilities for children and youth with physical disabilities?

2. Materials and Methods

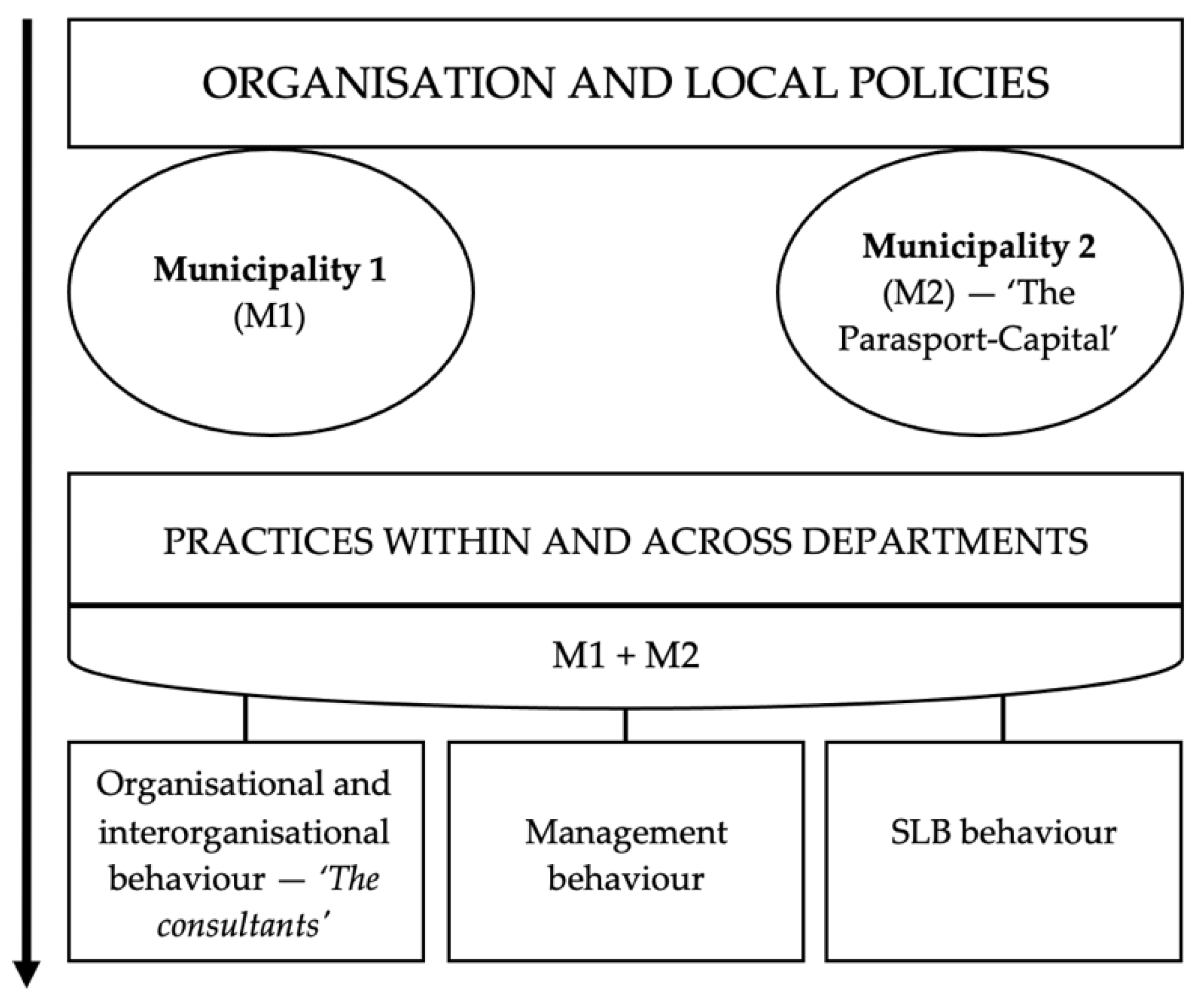

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Data Collection

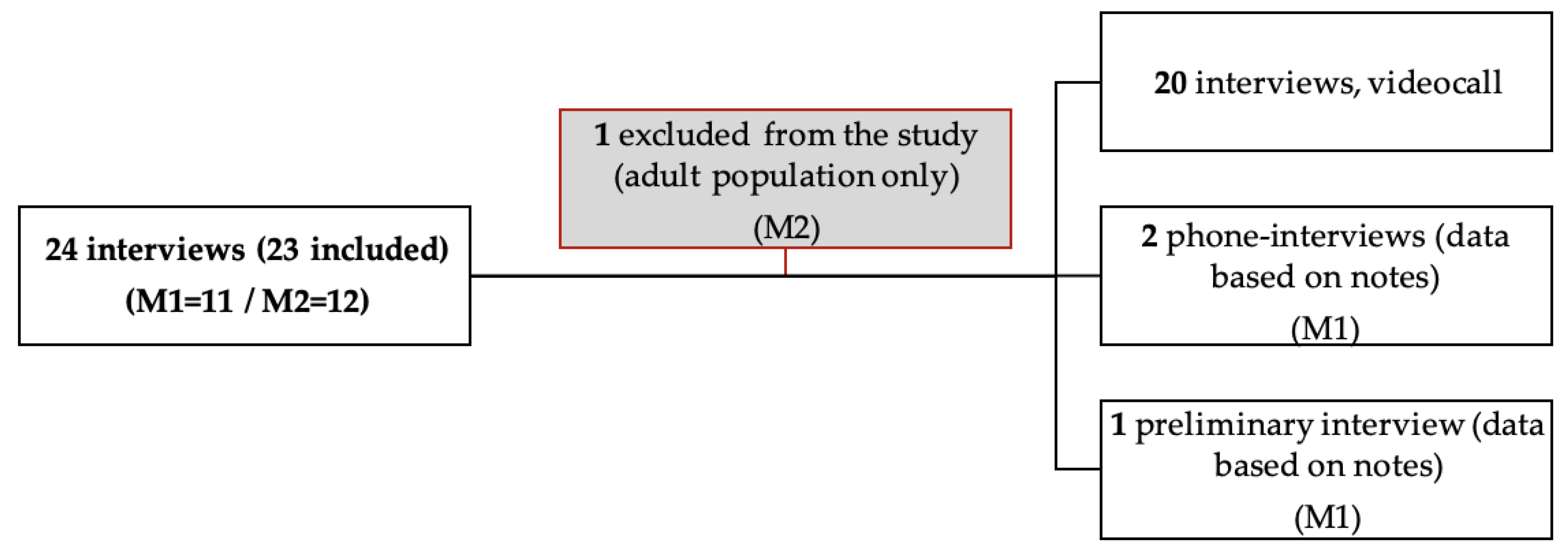

2.3.1. Interviews

2.3.2. Policy Documents

2.4. Analytical Strategy

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Organisation and Local Policies

3.1.1. Municipality 1 (M1)—A Brief Description of the Organisation of Local Authorities

The department does not contribute directly to children and youth with disabilities’ participation in PA, but uses the local Disability Policy to determine whether projects suggested by the local sports clubs can be approved.(Special consultant, M1. Notes from phone conversation.)

3.1.2. Municipality 1 (M1): The Influence and Usage of Policy Documents

Funnily enough they do not know we exist. I mean, those who can actually send them [the target group: Children and youth with disabilities] in our direction, they do not know we exist./…/The Family Department is equally surprised every time we contact them. When there is a new manager, we are forgotten. That is how we experience it anyway.(Sports consultant, the local Parasport Club, M1.)

She [the special consultant from Culture & Leisure] is our lifeline. I talk to her maybe four times a week.(Chairperson, the local Parasport Club, M1)

We have the Children & Youth Policy, and it is the bar to meet for all of us—that all children have the right to a good child life.(Manager, the Family Department, M1)

The one you just showed me [the Disability Policy], I did not know it.(Physiotherapist, PPR ‘ordinary’ schools, M1)

I do not remember them [the policies]. And if it states anything about children with special needs or children with physical or mental disabilities, I actually do not remember.(Pedagogical PE consultant, School Department, M1)

3.1.3. Municipality 2 (M2): “The Parasport Capital”—A Brief Description of the Organisation of Local Authorities

It provides good opportunities for competent feedback and discussions with the other caseworkers, to provide a holistic approach, in relation to the children and families.(Physiotherapeutic caseworker, Family & Handicap, M2)

3.1.4. Municipality 2 (M2): “The Parasport Capital”—The Influence and Usage of Policy Documents

The theme this year is called ‘The wheels are turning’. No matter what wheels you have, and how you move around, we can all participate in PA by some type of wheels./…/We chose this theme to include departments from Culture & Health.(Special consultant Children & Youth, M2)

That we have a clear vision to be the parasport capital forces us to move forward. It provides the possibilities to work with the area. An endorsement to spend energy on it, but also to go to other departments and say: ‘we actually have a political ambition, this is something all of us work on’. That is definitely a strength.(Manager, Sport, Event & Community, M2)

3.2. Practices within and across Departments (M1 + M2)

3.2.1. Organisational and Interorganisational Behaviour—The Consultants

It is difficult in my position, employed in Culture & Health, working with parasport but not having any direct interaction with the individual citizen./…/It is very much about being good in the communication flow and making your colleagues from other departments aware of the opportunities that exists.(Parasport consultant, M2)

3.2.2. Management Behaviour

Any good interdisciplinary collaboration requires management support. And within the parasport area we have strong support, built over years and now well-established.(Manager, Sport, Event & Community, M2)

It is really not something we focus on in our daily work.(Manager, Family & Handicap, M2)

We are lucky to not be bound by so many restrictions as many of the other departments, which we try to utilise to be part of the solution.(Manager, Sport, Event & Community, M2)

I think that where we have a focus is in relation to how we can compensate the families, so the children have the possibility to participate in some sport, if that is what they want.(Manager, Family Department, M1)

3.2.3. SLB Behaviour

Our job is to a large degree to manage these paragraphs [from the Act on Social Services], with the options being what lies within these. It kind of sets the framework.(Caseworker, Family Department, M1)

- Rationing services: Arguing that other services are of higher priority to explain why counselling on PA possibilities is given less of a priority;

- Standardising work: Fitting the target group into specific categories with regard to which sport activities can be supported and/or informed about. As the caseworker in M2 expressed:We kind of have to put them into boxes, because you cannot go to both wheelchair hockey, football, basket, wheelchair everything.(Caseworker, Family & Handicap, M2)

- Decreasing demands: Both by limiting user information and by imposing psychological costs on the target group; for instance, by using the fatigue of the child or the time/resources of the parents as an explanation for the individual not participating in PA.

I think we should focus more on how we can, to a larger degree, establish a dialogue and collaboration with the local organisations to utilise their connections and knowledge on possibilities. It is a lot of work for us to provide individual guidance in every case.(Physiotherapist, PPR, ‘ordinary’ schools, M1)

I think I am maybe a bit like Pippi Longstocking, even if there is something I have not tried before, I can probably do it. And then I seek guidance with the ones who know more, or I use the internet.(Teaching assistant, special school, M2)

I move a lot myself—bike, swim, and run—which I have tried to incorporate in my work the last few years./…/When you show that you think it is awesome to move, it transfers to the children.(Teaching assistant, special school, M1)

4. Discussion

4.1. Policies with Action Plans—A Starting Point for Increasing the Implementation of PA Possibilities across Multiple Municipal Levels

4.2. A Coordinating Function, Working across Departments, Is Key to High Performance

4.3. Identifying Shared Objectives and Collaboration across Different Municipal Levels—Room for Improvement

4.4. Individual SLB Behaviour Influences Municipal Performance

4.5. Limitations and Further Research

4.6. Recommendations for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Theme | Question | Support |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction and consent | Inform about consent—refer to document sent. Recording of the interview. Presentation of interviewer Purpose of the project:The project aims to describe and analyse how selected Danish municipalities work to support the opportunities for participation in physical activity for children and youth living with physical disabilities. | |

| Presentation of participant | Can you briefly present yourself and your area of work in the municipality? | |

| Objectives and performances on PA | What are the objectives of your department’s work? Through your work, how do you support children and youth with disabilities to be physically active? | |

| Incentives and capacity of SLBs | What are your qualifications for working with the target group and physical activity? Please include experience, competences, and knowledge Do you experience opportunities to seek out knowledge and support from colleagues, other departments in the municipality or from externals? What is your impression of your department’s attitude and prioritization of physical activities towards the target group? Do you have an interest in working with physical activity? And what about your colleagues? | Mention examples of organisations within the field as reference. Communication from managers, professional backing, possibilities for professional development courses etc. |

| Legislation/policies /strategies -Legislation: national level -Policies/strategies: municipal level | Are there any laws, regulations, policies and/or strategies, related to the field of physical activity for children/adolescents with disabilities, that guide your department’s work? How are these communicated from your management to you in your daily work? How are these integrated with practice? | Please describe the content etc. of such documents. (Offer examples). Work procedures etc. |

| Organisation | Which municipal departments or units will typically support children and/or young people with disabilities, and thereby influence their everyday life? | |

| Interdisciplinary collaboration Shared objectives | In what ways do you collaborate with other departments/areas in the municipality in relation to the target group? Does the municipality have specific objectives and/or strategies regarding physical activity for children and youth with disabilities that influence/guide your work? Is there a shared goal that you and others work towards? Is there a formulated, common position in relation to this target group? Do you face challenges with realizing such goals and/or position through your work? Are you familiar with internal or external councils/committees working with the area? | The possibility of collaboration, communication and coordination across departments? Offer examples of departments. Examples: Local handicap council; Parasport Denmark, etc. |

| Barriers and opportunities | In your opinion, what are some of the crucial barriers/opportunities to get children and youth with disabilities more active? | e.g., it is a challenge with transportation, support, information, contacts, etc. |

| Rounding | Do you have any further comments or questions? Do you have suggestions for additional people within municipal administration etc. that we should talk to on these matters? | |

Appendix B

| Categories | Definition | Example from Interviews | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practices within and across Departments | Organisational and interorganisational behaviour—the influence of consultants | Consultants influence collaborations across departments by communicating and coordinating policies, opportunities, and knowledge | “It is difficult in my position, employed in Culture & Health, working with parasport but not having any direct interaction with the individual citizen./…/It is very much about being good in the communication flow and making your colleagues from other departments aware of the opportunities that exists.” (Parasport consultant, M2) |

| SLB * behaviour | Individual incentives influence professional behaviour towards implementation of PA ** | “I think I am maybe a bit like Pippi Longstocking, even if there is something I have not tried before, I can probably do it. And then I seek guidance with the ones who know more, or I use the internet.” (Teaching assistant, special school, M2) | |

| Capacity challenge affects behaviour and use of coping strategies—barrier for implementation of PA | “Our job is to a large degree to manage these paragraphs [from the Act on Social Services], with the options being what lies within these. It kind of sets the framework.” (Caseworker, Family Department, M1) | ||

| Management behaviour | Management support and focus | “Any good interdisciplinary collaboration requires management support. And within the parasport area we have strong support, built over years and now well-established.” (Manager, Sport, Event & Community, M2) | |

| Lack of management support and focus | “It is really not something we focus on in our daily work.” (Manager, Family & Handicap, M2) |

References

- Shikako-Thomas, K.; Dahan-Oliel, N.; Shevell, M.; Law, M.; Birnbaum, R.; Rosenbaum, P.; Poulin, C.; Majnemer, A. Play and be happy? Leisure participation and quality of life in school-aged children with cerebral palsy. Int. J. Pediatr. 2012, 2012, 387280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Niedbalski, J. The Multi-Dimensional Influence of a Sports Activity on the Process of Psycho-Social Rehabilitation and the Improvement in the Quality of Life of Persons with Physical Disabilities. Qual. Sociol. Rev. 2018, 14, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carter, B.; Grey, J.; McWilliams, E.; Clair, Z.; Blake, K.; Byatt, R. ‘Just kids playing sport (in a chair)’: Experiences of children, families and stakeholders attending a wheelchair sports club. Disabil. Soc. 2014, 29, 938–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.M. Bevægelsesdeltagelse Blandt Mennesker Med Svære Funktionsnedsættelser. Videnscenter om handicap. handicap, V.o. 2020. Available online: https://videnomhandicap.dk/da/nyheder/nyt-notat-saetter-fokus-pa-bevaegelsesdeltagelse-blandt-mennesker-med-svaere-funktionsnedsaettelser/ (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Martin Ginis, K.A.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Foster, C.; Lai, B.; McBride, C.B.; Ng, K.; Pratt, M.; Shirazipour, C.H.; Smith, B.; Vásquez, P.M. Participation of people living with disabilities in physical activity: A global perspective. Lancet 2021, 398, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.M. Betydningsfulde Oplevelser. Udviklingsprocesser for Unge Og Voksne Med Cerebral Parese Gennem Resiliensbaserede Sociale Tilpassede Idræts- og Bevægelsesindsatser. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). 2006. Available online: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convention_accessible_pdf.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Kissow, A.-M.; Klasson, L. Rapport: Børn med funktionsnedsættelser deltager i færre skole- og fritidsaktiviteter—En systematisert kunnskapsoversikt. Nasjonal kompetansetjeneste for barn og unge med funksjonsnedsettelser|Aktiv Ung. 2018. Available online: https://videnomhandicap.dk/da/vores-temaer/inklusion-i-skolen/rapport-born-med-funktionsnedsaettelser-deltager-i-faerre-skole-og-fritidsaktiviteter/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Michelsen, S.I.; Flachs, E.M.; Damsgaard, M.T.; Parkes, J.; Parkinson, K.; Rapp, M.; Arnaud, C.; Nystrand, M.; Colver, A.; Fauconnier, J. European study of frequency of participation of adolescents with and without cerebral palsy. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2014, 18, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carlon, S.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Dodd, K.J.; Shields, N. Differences in habitual physical activity levels of young people with cerebral palsy and their typically developing peers: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloemen, M.A.; Backx, F.J.; Takken, T.; Wittink, H.; Benner, J.; Mollema, J.; De Groot, J.F. Factors associated with physical activity in children and adolescents with a physical disability: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014, 57, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanagasabai, P.S.; Mulligan, H.; Devan, H.; Mirfin-Veitch, B.; Hale, L.A. Environmental factors influencing leisure participation of children with movement impairments in Aotearoa/New Zealand: A mixed method study. N. Z. J. Physiother. 2019, 47, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, C.; Girdler, S.; Thompson, M.; Rosenberg, M.; Reid, S.; Elliott, C. Elements contributing to meaningful participation for children and youth with disabilities: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 1771–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Ploeg, H.P.; Van der Beek, A.J.; Van der Woude, L.H.; van Mechelen, W. Physical Activity for People with a Disability. A Conceptual Model. Sports Med. 2004, 34, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Ginis, K.A.; Ma, J.K.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Rimmer, J.H. A systematic review of review articles addressing factors related to physical activity participation among children and adults with physical disabilities. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, N.; Synnot, A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2016, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bevica Fonden, Børn og unge med bevægelseshandicaps muligheder for at deltage i fysisk aktivitet. 2018; Unpublished manuscript.

- The Ministry for Economic Affairs and the Interior (MEAI). Municipalities and Regions—Tasks and Financing. 2014. Available online: https://english.im.dk/responsibilities-of-the-ministry/governance-of-municipalities-and-regions/about-municipalities-and-regions (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Det Centrale Handicapråd (DCH). Nye Kommunale Handicappolitikker—Inspiration til at Udvikle Handicappolitik Med Handling og Fremdrift. 2020. Available online: https://dch.dk/kommunale-handicapraad/pjecer-kommunale-handicapraad (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Ministry for Children and Social Affairs. Act on Social Services, Ref. No. 2018-3828. 2018. Available online: https://english.sim.dk/media/32805/engelsk-oversaettelse-af-bekendtgoerelse-af-lov-om-social-service-2018-opdateret-juni-2019.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Winter, S.C.; Nielsen, V.L. Implementering af Politik, 1st ed.; Academica: Århus, Denmark, 2008; ISBN 9788776755904/8776755908. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky, M. Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services, 30th anniversary expand ed.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780871545442/0871545446. [Google Scholar]

- Baviskar, S.; Winter, S.C. Street-level bureaucrats as individual policymakers: The relationship between attitudes and coping behavior toward vulnerable children and youth. Int. Public. Manag. J. 2017, 20, 316–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovgaard, T.; Johansen, D.L.N. School-Based Physical Activity and the Implementation Paradox. Adv. Phys. Educ. 2020, 10, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittell, J.H. Effektivitet I Sundhedsvæsenet: Samarbejde, Fleksibilitet Og Kvalitet; Munksgaard: København, Danmark, 2012; ISBN 9788762811362/8762811363. [Google Scholar]

- Gittell, J.H. Relationers Betydning for Høj Effektivitet: Styrken ved Relationel Koordinering, 1st ed.; Dansk Psykologisk Forlag: København, Danmark, 2016; ISBN 8771585273/9788771585278. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 1452242569/9781452242569. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Weate, P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise; Smith, B., Sparkes, A.C., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kanagasabai, P.S.; Mulligan, H.; Mirfin-Veitch, B.; Hale, L.A. “I do like the activities which I can do…” Leisure participation experiences of children with movement impairments. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.C. Explaining street-level bureaucratic behavior in social and regulatory policies. In Proceedings of the 2002 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Boston, MA, USA, 29 August–1 September 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Area | Department | Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Children and Youth | The School Department | Managers: Director Manager, special school |

| SLBs: Teaching assistant, special school | ||

| Consultants: Pedagogical PE consultant | ||

| The Family Department, Section for Special Needs | Managers: Manager | |

| SLBs: Caseworker | ||

| The Department of Pedagogical and Psychological Consultation (PPR) | SLBs: Physiotherapist, special school Physiotherapist, “ordinary” school | |

| City, Culture, and Environment | The Department of Culture and Leisure | Special consultant |

| Local Parasport Club | Chairperson Sports consultant Volunteer | |

| Local Sports Organisation | Sports consultant |

| Area | Department | Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children and Youth | The Children and Youth Staff Department | Consultants: Chief consultant | |

| The School Department | Managers: Manager, special school + the children and youth training centre (located at the school) SLBs: Teaching assistant, special school Physiotherapist, special school + the children and youth training centre Consultants: Pedagogical consultant | ||

| The Department of Family and Prevention | Family and Handicap | Managers: Manager SLBs: Caseworker Physiotherapeutic caseworker | |

| Interdisciplinary Centre for Children and Youth (PPR) | Managers: Manager SLBs: Physiotherapist | ||

| Culture and Health | The Department of Sport, Event, and Community | Managers: Top manager Consultants: Parasport consultant | |

| Policy Documents, M1 | Topics |

|---|---|

| Disability Policy, 2019–2022 | Equal opportunity to participate in sports (including transportation, physical access, and information). |

| An individual holistic approach that is coordinated across departments and the local community. | |

| Action Plan for the Disability Policy, 2020 | Initiative 1: A communication group for parents of children with disabilities. Initiative 6: Initiatives within the local parasport club: (1) funding for recruitment of schoolchildren with disabilities, and (2) swimming for children with cerebral palsy. Initiative 7: An open sport facility, facilitating participation for all. Initiative 8: Exercise for all—educate volunteers in the inclusion of people with disabilities. |

| Health Policy, 2019–2022 | Reducing social inequalities in health. More children and youth should participate in PA. |

| Cross-sectional collaborations, including support for local sports organisations. | |

| Coherent Child Policy, 2016 | Children and youth with disabilities should have the same opportunities to participate in society as their peers. |

| A high priority on leisure activities for children with physical disabilities. | |

| A holistic and interdisciplinary approach across departments. | |

| Sport and Movement Policy, 2019–2022 | All citizens should experience possibilities for PA. |

| Policy Documents, M2 | Topics |

|---|---|

| Disability Policy, 2019–2027 | Inclusion is a joint responsibility: the individual and family must feel adequately guided across departments. |

| Equal opportunities for participation in the community, and to live healthy and active lives. The wish to be leading within parasport. | |

| Action Plan (Parasport Council), 2020–2021 | Support local sports clubs to become capable of including citizens with disabilities by: (1) focusing on schools’ collaborations with local clubs and Parasport Denmark; (2) support the local clubs by strengthening competences; and (3) create awareness of the local parasport fund and application opportunities. |

| The promotion of interdisciplinary collaborations within the municipality. | |

| Children and Youth Policy (disability), 2013 | Facilitate self-esteem, health, and well-being—this is the start of growth. |

| Children and youth with disabilities should experience the same opportunities to participate in leisure-time activities. | |

| Strategy for Family and Prevention 2017–2020: “We want more—together” | The strengthening of health promotion and interdisciplinary collaborations to create a coherent experience for families. |

| Health Policy, 2017–2024 | All children and youth should have access to movement and sports activities. The involvement of the entire municipality in the achievement of health. |

| Culture, Sports, and Leisure Policy: “The best place to live”, 2019–2022 | The municipality focuses on parasport. The sports environment should be accessible and open to all. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Præst, C.B.; Skovgaard, T. Physical Activity for Children and Youth with Physical Disabilities: A Case Study on Implementation in the Municipality Setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105791

Præst CB, Skovgaard T. Physical Activity for Children and Youth with Physical Disabilities: A Case Study on Implementation in the Municipality Setting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):5791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105791

Chicago/Turabian StylePræst, Charlotte Boslev, and Thomas Skovgaard. 2022. "Physical Activity for Children and Youth with Physical Disabilities: A Case Study on Implementation in the Municipality Setting" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 5791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105791

APA StylePræst, C. B., & Skovgaard, T. (2022). Physical Activity for Children and Youth with Physical Disabilities: A Case Study on Implementation in the Municipality Setting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 5791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105791