Self-Criticism in In-Work Poverty: The Mediating Role of Social Support in the Era of Flexibility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Complexity and limitations of the Concept

1.2. In-Work Poverty and Health

1.3. Social Support and Wellbeing in Contexts of Precariousness

1.4. Coping Strategies and Labour Activation

1.5. This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Analysis

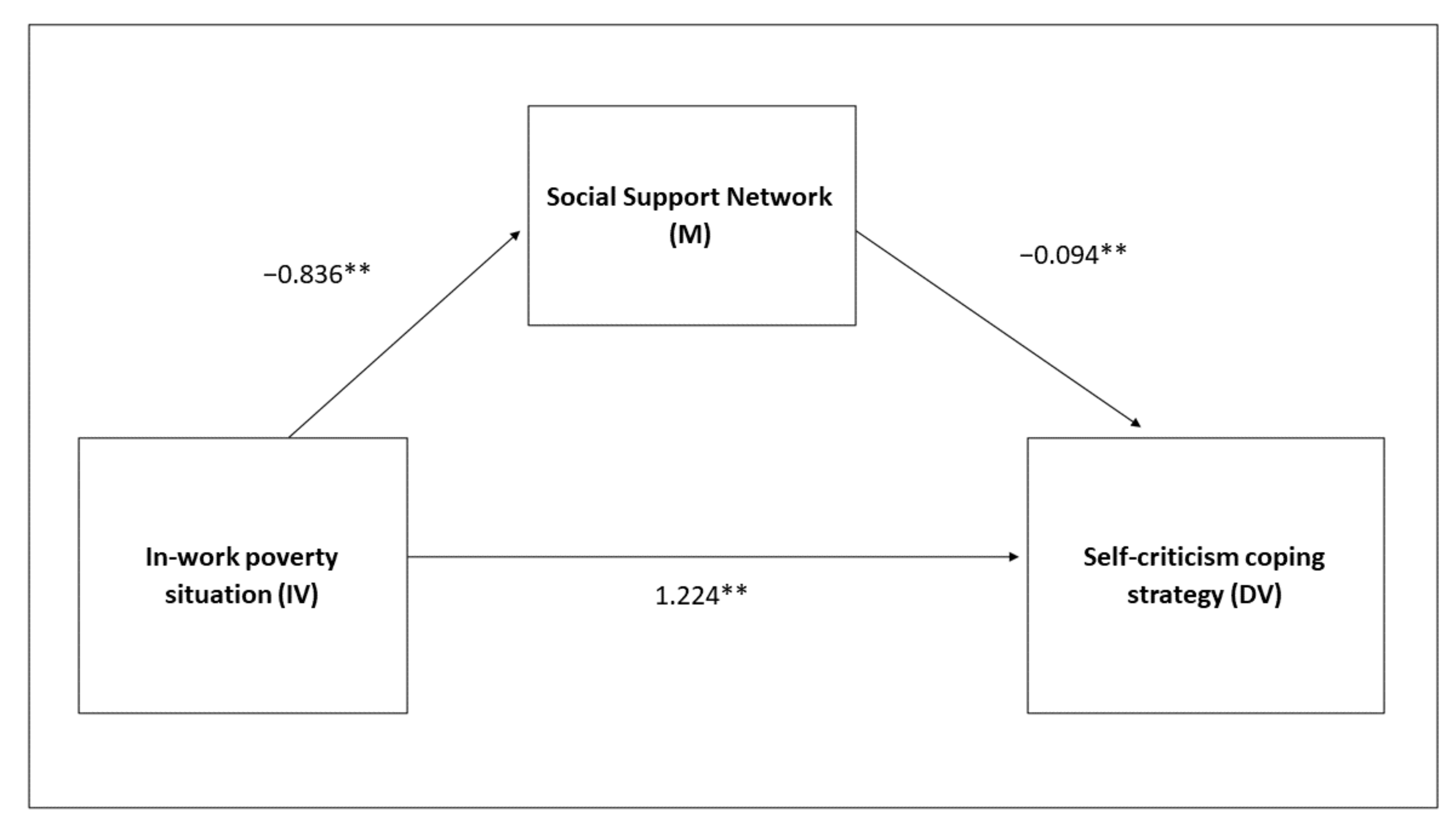

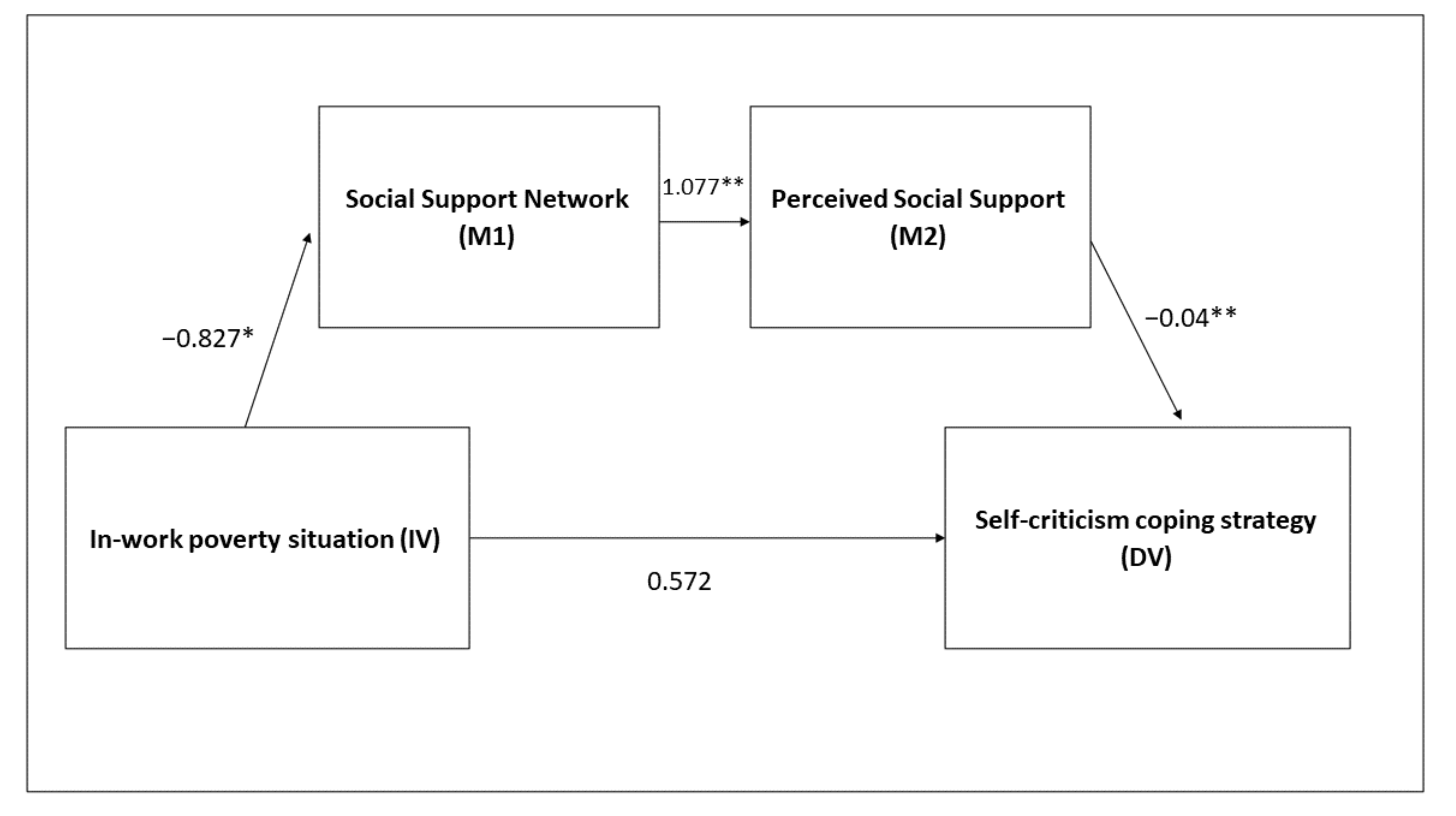

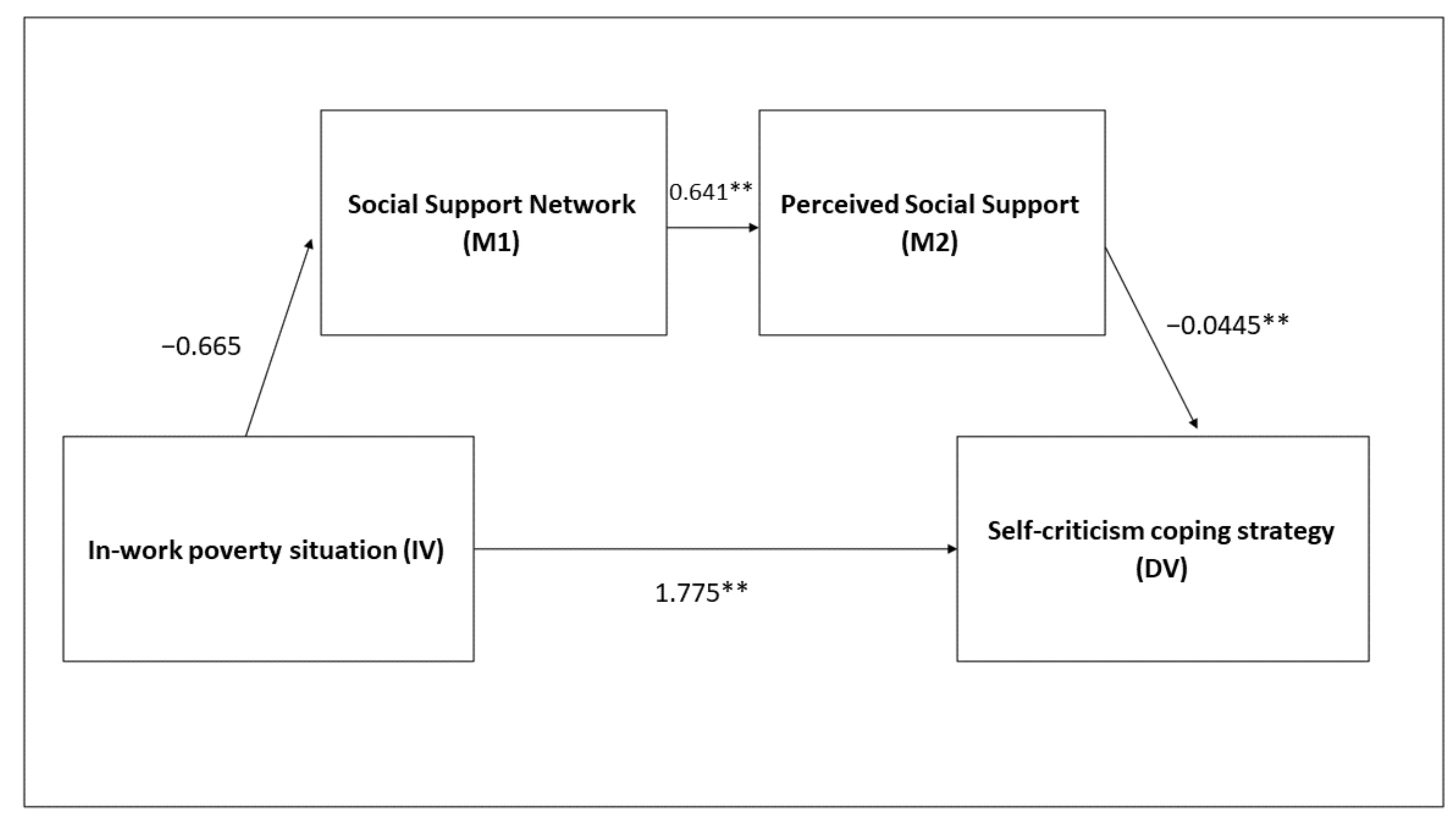

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Self-Criticism Strategy among People in a Situation of In-Work Poverty

4.2. Social Support as a Mediating Variable of Self-Criticism

4.3. Gender Differences in In-Work Poverty

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Labour Organization. The Working Poor, or How a Job Is No Guarantee of Decent Living Conditions; Ilostat; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Halleroed, B.; Ekbrand, H.; Bengtsson, M. In-Work Poverty and Labour Market Trajectories: Poverty Risks among the Working Population in 22 European Countries. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2015, 25, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, N.-S.; Verwiebe, R. Labor Market Flexibilization and In-Work Poverty: A Comparative Analysis of Germany, Austria and Switzerland. In Handbook of Research on In-Work Poverty; Lohmann, H., Marx, I., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 297–311. ISBN 9781784715632. [Google Scholar]

- Laporsek, S.; Dolenc, P. Do Flexicurity Policies Affect Labour Market Outcomes? An Analysis of EU Countries. Rev. Za Soc. Polit. 2012, 19, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnold, D.; Bongiovi, J.R. Precarious, Informalizing, and Flexible Work: Transforming Concepts and Understandings. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benach, J.; Amable, M.; Muntaner, C.; Benavides, F. The Consequences of Flexible Work for Health: Are We Looking at the Right Place? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2002, 56, 405–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levanon, A. Labor Market Insiders or Outsiders? A Cross-National Examination of Redistributive Preferences of the Working Poor. Societies 2018, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andrade Jaramillo, V. Identidad profesional y el mundo del trabajo contemporáneo. Reflexiones desde un resumen de caso. Athenea Digit. Rev. Pensam. E Investig. Soc. 2014, 14, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallie, D. Production Regimes, Employment Regimes, and the Quality of Work. In Employment Regimes and the Quality of Work; Gallie, D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 18–51. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaría López, E.; Serrano Pascual, A. Precarización e Individualización del Trabajo: Claves Para Entender y Transformar la Realidad laboral [Precarization and Individualization of Work: Keys to Understanding and Transforming the Reality of Work]; Editorial UOC: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Martin, R.; Manuel Garcia-Moreno, J.; Manuel Lozano-Martin, A. Working Poor in Spain. The Context of the Economic Crisis as a Framework for Understanding Inequality. Pap. Poblac. 2018, 24, 185–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poy Piñeiro, S. Working Poor in Argentina and Spain: A Comparative Analysis Focused on Labour Market Inequalities. Pap.-Rev. Sociol. 2021, 106, 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero, A. In-Work Poverty Persistence: The Influence of Past Poverty on the Present. Rev. Esp. Investig. Sociol. 2017, 157, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) Methodology-in-Work Poverty; Eurostat: Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Filandri, M.; Pasqua, S.; Struffolino, E. Being Working Poor or Feeling Working Poor? The Role of Work Intensity and Job Stability for Subjective Poverty. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 147, 781–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EAPN España. El Estado de La Pobreza: Seguimiento Del Indicador de Pobreza y Exclusión Social En España 2008–2020 [The State of Poverty: Monitoring the Poverty and Social Exclusion Indicator in Spain, 2008–2020]; EAPN España: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Maitre, B.; Nolan, B.; Whelan, C.T. Low Pay, in-Work Poverty and Economic Vulnerability: A Comparative Analysis Using EU-SILC. Manch. Sch. 2012, 80, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crettaz, E.; Bonoli, G. Why Are Some Workers Poor? The Mechanisms That Produce Working Poverty in a Comparative Perspective; Working Papers; RECWOWE Publication: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, I.; Vanhille, J.; Verbist, G. Combating In-Work Poverty in Continental Europe: An Investigation Using the Belgian Case. J. Soc. Policy 2012, 41, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horemans, J.; Marx, I.; Nolan, B. Hanging in, but Only Just: Part-Time Employment and in-Work Poverty throughout the Crisis. IZA J. Eur. Labor Stud. 2016, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nieuwenhuis, R.; Maldonado, L.C. Single-Parent Families and in-Work Poverty. In Handbook of Research on In-Work Poverty; Lohmann, H., Marx, I., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 171–193. ISBN 9781784715632. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, I.; Nolan, B. In-Work Poverty. In Reconciling Work and Poverty Reduction: How Successful Are European Welfare States? Cantillon, B., Vandenbroucke, F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 131–156. [Google Scholar]

- Broding, H.C.; Weber, A.; Glatz, A.; Buenger, J. Working Poor in Germany: Dimensions of the Problem and Repercussions for the Health-Care System. J. Public Health Policy 2010, 31, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfoertner, T.-K.; Schmidt-Catran, A.W. In-Work Poverty and Self- Rated Health in a Cohort of Working Germans: A Hybrid Approach for Decomposing Within-Person and Between-Persons Estimates of In-Work Poverty Status. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 185, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuda, Y.; Ohde, S.; Takahashi, O.; Hinohara, S.; Fukui, T.; Inoguchi, T.; Butler, J.P.; Ueda, S. Influence of Income on Health Status and Healthcare Utilization in Working Adults: An Illustration of Health Among the Working Poor in Japan; Inoguchi, T., Tokuda, Y., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 177–190. ISBN 9789811023057. [Google Scholar]

- Topete, L.; Forst, L.; Zanoni, J.; Friedman, L. Workers’ Compensation and the Working Poor: Occupational Health Experience among Low Wage Workers in Federally Qualified Health Centers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2018, 61, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinonez, C.; Figueiredo, R. Sorry Doctor, I Can’t Afford the Root Canal, I Have a Job: Canadian Dental Care Policy and the Working Poor. Can. J. Public Health-Rev. Can. Sante Publique 2010, 101, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinafi, T. Illness and psychopharmaceutical drugs: Addiction in post-modernity. Nómadas 2013, 39, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko, S.; Courtin, E.; Fiorillo, A.; Knapp, M.; Luciano, M.; Park, A.-L.; Brunn, M.; Byford, S.; Chevreul, K.; Forsman, A.K.; et al. The State of the Art in European Research on Reducing Social Exclusion and Stigma Related to Mental Health: A Systematic Mapping of the Literature. Eur. Psychiatry 2014, 29, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.Y.; Sangjun, K. Study on Factors Affecting Depression of Working Poor-Hierarchical Regression Analysis of Income, Health, Housing, Labor and Drinking Factors by Gender. Stud. Life Cult. 2020, 55, 79–107. [Google Scholar]

- Llosa, J.A.; Agullo-Tomas, E.; Menendez-Espina, S.; Rodriguez-Suarez, J.; Boada-Grau, J. Job Insecurity, Mental Health and Social Support in Working Poor. Athenea Digit. 2020, 20, e2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rimnacova, Z.; Kajanova, A. Stress and the Working Poor. Hum. Aff.-Postdisciplinary Humanit. Soc. Sci. Q. 2019, 29, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, M.J.; Solheim, C.; Wolfgram, S.; Nkosi, B.; Rodrigues, N. The Working Poor: From the Economic Margins to Asset Building. Fam. Relat. 2004, 53, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Rogalsky, J. Bartering for Basics: Using Ethnography and Travel Diaries to Understand Transportation Constraints and Social Networks among Working-Poor Women. Urban Geogr. 2010, 31, 1018–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, B.C.; Collins, N.L. A New Look at Social Support: A Theoretical Perspective on Thriving Through Relationships. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 19, 113–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangopadhyay, P.; Shankar, S.; Rahman, M.A. Working Poverty, Social Exclusion and Destitution: An Empirical Study. Econ. Model. 2014, 37, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, C.S.C.; Yu, E.Y.T.; Guo, V.Y.; Wong, C.K.H.; Kung, K.; Ho, S.Y.; Lam, L.Y.; Ip, P.; Fong, D.Y.T.; Lam, D.C.L.; et al. Development of a Health Empowerment Programme to Improve the Health of Working Poor Families: Protocol for a Prospective Cohort Study in Hong Kong. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hwang, A.-R.; Bokyeung, S. Citizen Satisfaction of the Policy on the Working Poor. Korean Public Adm. Q. 2013, 25, 171–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N. Citizenship Narratives in the Face of Bad Governance: The Voices of the Working Poor in Bangladesh. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 325–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradella, L. The Working Poor in Western Europe: Labour, Poverty and Global Capitalism. Comp. Eur. Polit. 2015, 13, 596–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seikel, D. Activation into In-Work Poverty? Soc. Eur. 2017, 1, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, E.; Serrano, A. Paradoxes of European Employment Policies: From Fairness towards Therapy. Univ. Psychol. 2013, 12, 1113–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Crespo, E.; Serrano, A. La Psicologización Del Trabajo: La Desregulación Del Trabajo y El Gobierno de Las Voluntades [The psychologization of work: The deregulation of work and the government of the will]. In Contra-Psicología: De las Luchas Antipsiquiátricas a la Psicologización de la Cultura; Rodríguez López, R., Ed.; Dado Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2016; pp. 273–296. [Google Scholar]

- Llosa, J.A.; Menéndez-Espina, S.; Agulló-Tomás, E.; Rodríguez-Suárez, J.; Lasheras-Díez, H.; Saiz-Villar, R. The work psychopatologisation: The discomfort state of the responsible subject. Aposta Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2019, 80, 82–97. [Google Scholar]

- Skilling, P.; Tregidga, H. Accounting for the “Working Poor”: Analysing the Living Wage Debate in Aotearoa New Zealand. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2019, 32, 2031–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Elst, T.; Richter, A.; Sverke, M.; Näswall, K.; De Cuyper, N.; De Witte, H. Threat of Losing Valued Job Features: The Role of Perceived Control in Mediating the Effect of Qualitative Job Insecurity on Job Strain and Psychological Withdrawal. Work Stress 2014, 28, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. The Psychology of Globalization. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Espina, S.; Llosa, J.A.; Agulló-Tomás, E.; Rodríguez-Suárez, J.; Sáiz-Villar, R.; Lahseras-Díez, H.F. Job Insecurity and Mental Health: The Moderating Role of Coping Strategies From a Gender Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sherbourne, C.D.; Stewart, A.L. The MOS Social Support Survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla Ahumada, L.; Luna del Castillo, J.; Bailón Muñoz, E.; Medina Moruno, I. Validation of a questionnaire to measure Social Support in primary care. Med. Fam. 2005, 6, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin, D.L.; Holroyd, K.A.; Reynolds, R.V.C. Coping Strategies Inventory. CSI Man. 1984, 3, 343–361. [Google Scholar]

- Cano-García, F.J.; Rodríguez-Franco, L.; Garcia-Martínez, J. Spanish version of the Coping Strategies Inventory. Actas Esp. Psiquiatría 2007, 35, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Simkunas, D.P.; Thomsen, T.L. Precarious Work? Migrants’ Narratives of Coping with Working Conditions in the Danish Labour Market. Cent. East. Eur. Migr. Rev. 2018, 7, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Farias, K.K.; Bezerra, W.C. Institutional conditions and coping strategies of precarious work conditions for occupational therapists in public hospitals. Cad. Ter. Ocup. Ufscar 2016, 24, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, C.R. The Individual Experience of Unemployment. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, M.; Gershenson, C. Housing and Employment Insecurity among the Working Poor. Soc. Probl. 2016, 63, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.-C. Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power; Verso Books: Cheltenham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, I. Capitalismo, Locura y Justicia Social [Capitalism, madness and social justice]. In Contra-Psicología: De las Luchas Antipsiquiátricas a la Psicologización de la Cultura; Rodríguez López, R., Ed.; Dado Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2016; pp. 113–140. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.O.; Wilson, M.G.; Lee, M.S. Effects of Social Support at Work on Depression and Organizational Productivity. Am. J. Health Behav. 2004, 28, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariepy, G.; Honkaniemi, H.; Quesnel-Vallee, A. Social Support and Protection from Depression: Systematic Review of Current Findings in Western Countries. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 209, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieselbach, T. Long-Term Unemployment among Young People: The Risk of Social Exclusion. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2003, 32, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, L.; McKee, K.J.; Fritzell, J.; Heap, J.; Lennartsson, C. Trends and Gender Associations in Social Exclusion in Older Adults in Sweden over Two Decades. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 89, 104032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, G. Care, Autonomy, and Justice: Feminism and The Ethic of Care; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pena-Casas, R.; Ghailani, D. Towards Individualizing Gender In-Work Poverty Risks; Fraser, N., Gutierrez, R., PenaCasas, R., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2011; pp. 202–231. ISBN 9780230307599. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler, K.S.; Myers, J.; Prescott, C.A. Sex differences in the relationship between social support and risk for major depression: A longitudinal study of opposite-sex twin pairs. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M. Social Support Research in Community Psychology. In Handbook of Community Psychology; Rappaport, J., Seidman, E., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 215–245. ISBN 9781461541936. [Google Scholar]

| In-Work Poverty | Age (SD) | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not In-Work Poverty | In-Work Poverty | |||

| Women | 579 | 193 | 36.02 (11.58) | 772 |

| Men | 545 | 112 | 34.28 (12.61) | 658 |

| Total | 1124 | 305 | 35.22 (12.1) | 1430 |

| 1. Self-Criticism | 2 | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Perceived Social Support | −0.17 ** | 1430 | |

| 3. Social Support Network | −0.11 ** | 0.28 ** |

| Self-Criticism | Perceived Social Support | Social Support Network | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | T | M (SD) | T | M (SD) | T | |

| Total sample | ||||||

| In-work poverty | 12.62 (4.91) | −4.17 ** | 74.32 (17.16) | 5.09 ** | 8.15 (4.59) | 2.62 * |

| Not in-work poverty | 11.32 (4.56) | 79.71 (14.64) | 8.98 (4.58) | |||

| Women | ||||||

| In-work poverty | 12.18 (4.86) | −2.12 * | 75.08 (17.14) | 3.34 ** | 7.88 (3.96) | 2.22 * |

| Not in-work poverty | 11.37 (4.52) | 79.68 (14.87) | 8.7 (4.64) | |||

| Men | ||||||

| In-work poverty | 13.4 (4.92) | −4.4 * | 72.77 (17.16) | 4.5 ** | 8.62 (5.5) | 1.18 |

| Not in-work poverty | 11.28 (4.6) | 79.73 (14.4) | 9.28 (5.4) | |||

| Effect | Boot SE | p | N (Men and Women) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Effect: (IV In-work poverty situation -> DV Self-criticism) | 1.3 ** | 0.3 | 0.000 | 1430 |

| Effect | Boot SE | CI 95% | N (Men and Women) | |

| Indirect Effect: (In-work poverty situation -> Social Support Network -> Self-criticism) | 0.08 * | 0.04 | [0.02; 0.16] | 1430 |

| Mediation: (In-work poverty situation -> Social Support Network -> Self-criticism) | 0.26 * | 0.07 | [0.13; 0.041] |

| Indirect Effect | Effect | Boot SE | CI (95%) | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | |||||

| In-work poverty situation -> Social Support Network -> Perceived Social Support -> Self-criticism | 0.4 * | 0.02 | [0.004; 0.084] | 772 | |

| Hombres | |||||

| In-work poverty situation -> Social Support Network -> Perceived Social Support -> Self-criticism | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.013; 0.064] | 658 | |

| In-work poverty situation -> Perceived Social Support -> Self-criticism | 0.04 * | 0.04 | [0.12; 0.65] | 658 | |

| In-work poverty situation -> Social Support Network -> Self-criticism | 0.29 | 0.12 | [0.096; 0.561] | 658 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llosa, J.A.; Agulló-Tomás, E.; Menéndez-Espina, S.; Rivero-Díaz, M.L.; Iglesias-Martínez, E. Self-Criticism in In-Work Poverty: The Mediating Role of Social Support in the Era of Flexibility. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010609

Llosa JA, Agulló-Tomás E, Menéndez-Espina S, Rivero-Díaz ML, Iglesias-Martínez E. Self-Criticism in In-Work Poverty: The Mediating Role of Social Support in the Era of Flexibility. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010609

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlosa, José Antonio, Esteban Agulló-Tomás, Sara Menéndez-Espina, María Luz Rivero-Díaz, and Enrique Iglesias-Martínez. 2022. "Self-Criticism in In-Work Poverty: The Mediating Role of Social Support in the Era of Flexibility" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010609

APA StyleLlosa, J. A., Agulló-Tomás, E., Menéndez-Espina, S., Rivero-Díaz, M. L., & Iglesias-Martínez, E. (2022). Self-Criticism in In-Work Poverty: The Mediating Role of Social Support in the Era of Flexibility. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 609. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010609