Listening to Caregivers’ Voices: The Informal Family Caregiver Burden of Caring for Chronically Ill Bedridden Elderly Patients

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Context and Theoretical Background

2.1. Context of Bedridden Elderly Patients in Thailand

2.2. Palliative Care

2.3. Informal Family Caregiver Burden

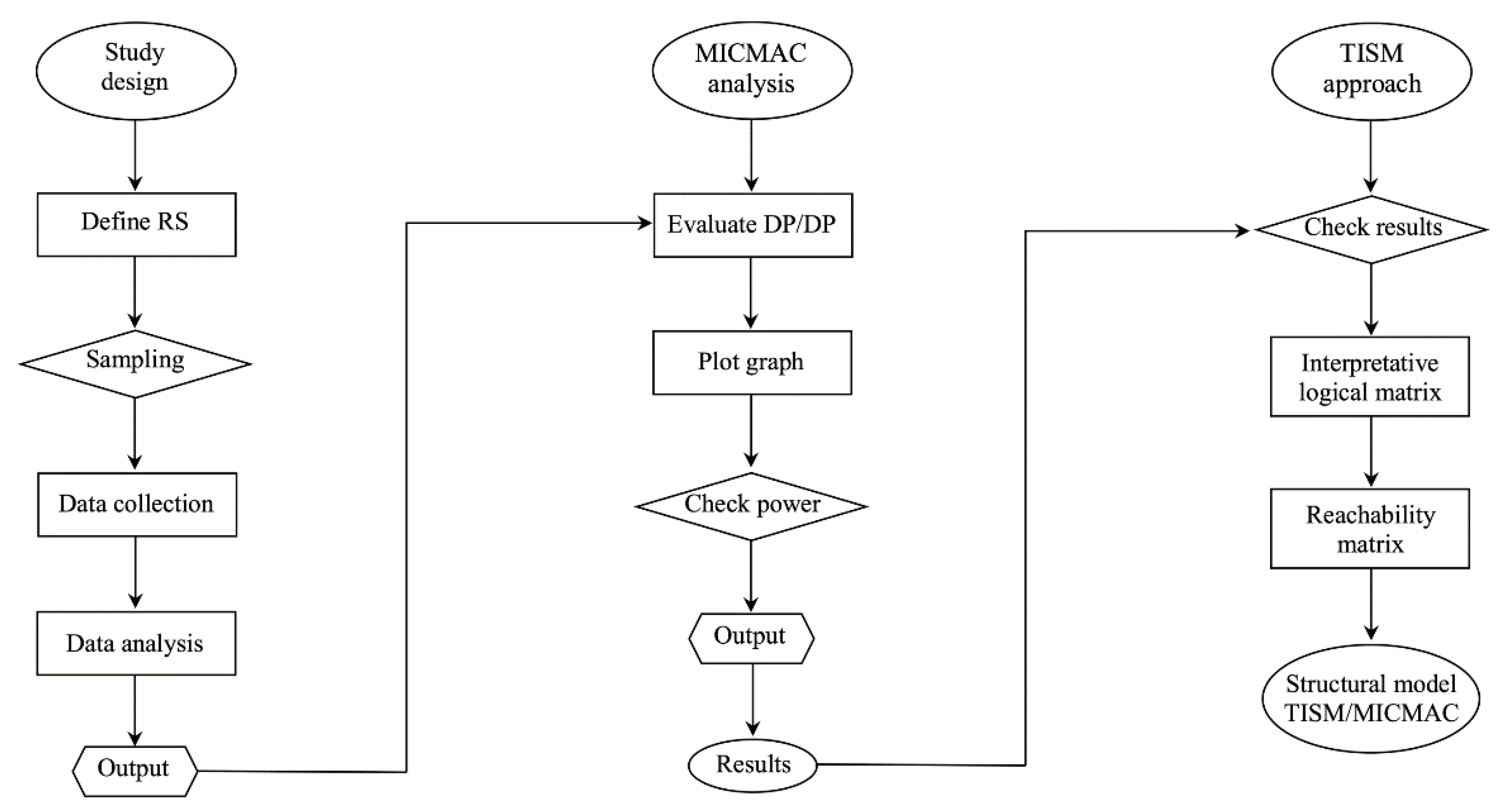

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Respondents and Sampling

3.3. In-Depth Interview Questions

3.4. Data Analysis

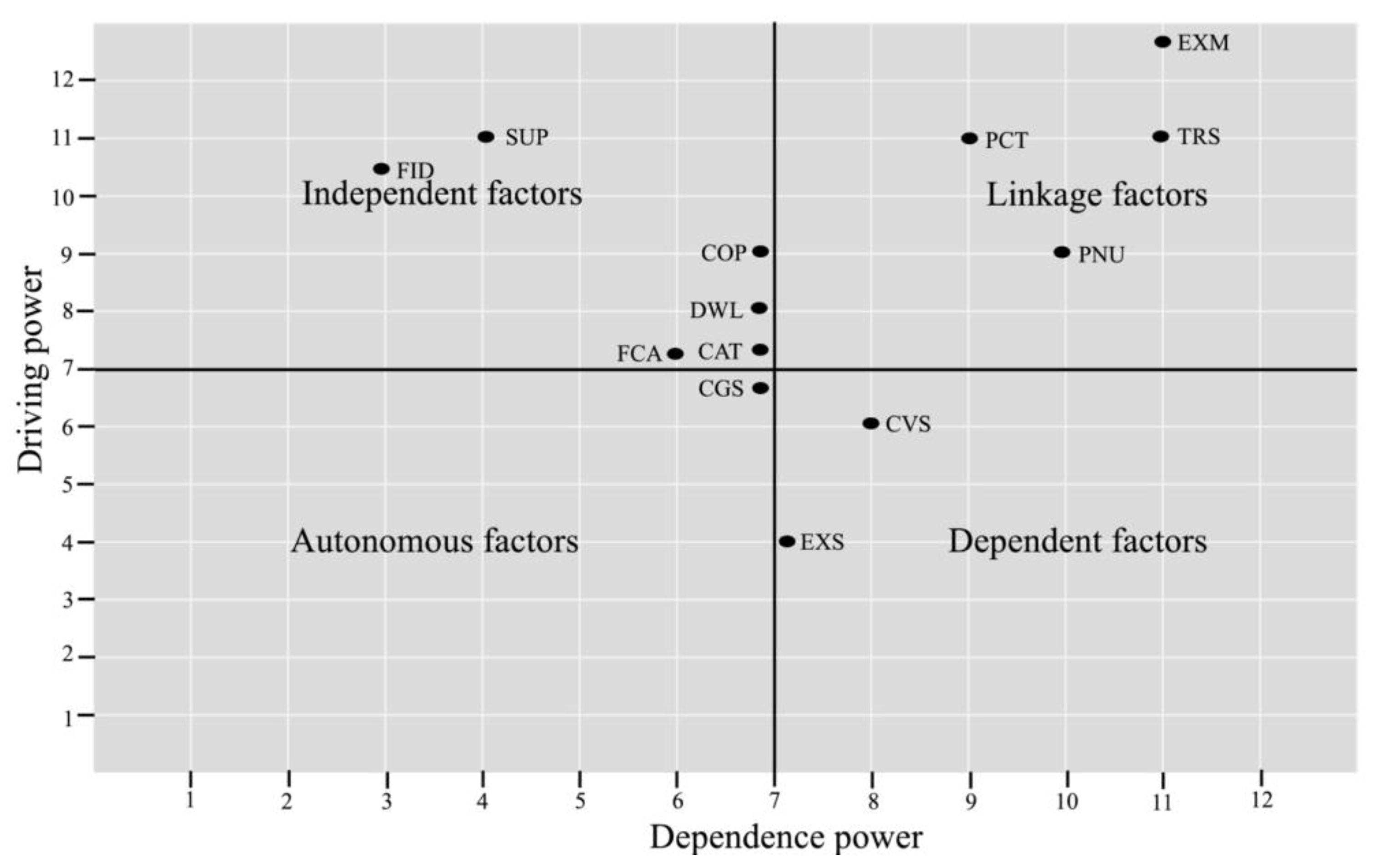

- Autonomous factors are both weak driving and dependence powers, which disconnect with others but are strongly linked with a few strong factors.

- Linkage factors are both strong driving and dependence powers, that is, factors act as linking (bridge) connectors with autonomous/dependent factors, which connect with independent factors.

- Dependent factors are less influential powers but have strong dependence power that influences the linkage/independent factors.

- Independent factors are strong influencing autonomous/dependent factors, which also are a strong driving power but have less dependence power.

3.5. Data Validity

4. Results

4.1. Interpretive Logic Matrix

- V: element i will help to achieve factor j;

- A: element j will help to achieve factor i;

- X: element i and j will help to achieve each other;

- O: element i and j are unrelated.

4.2. Reachability Matrix

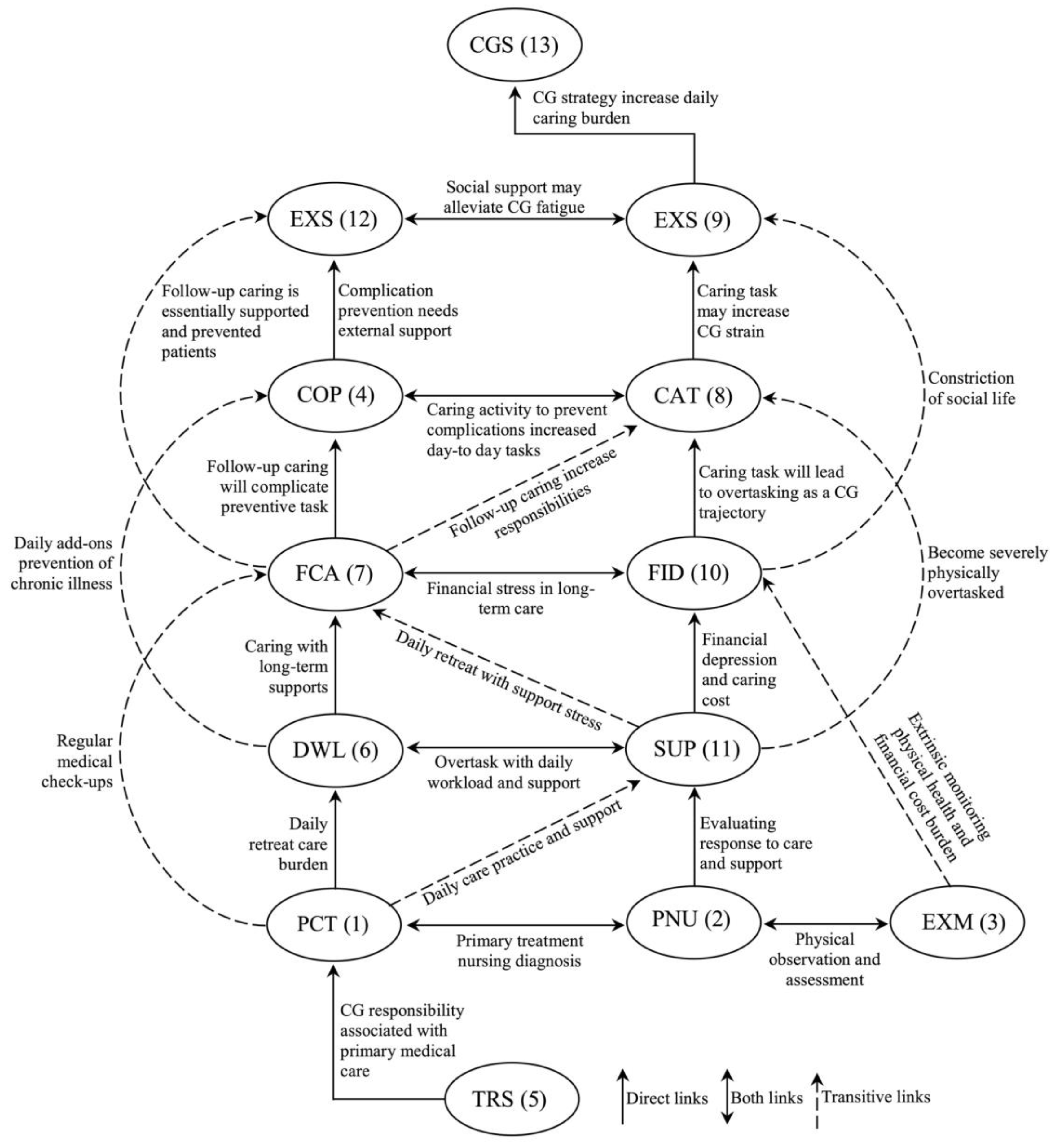

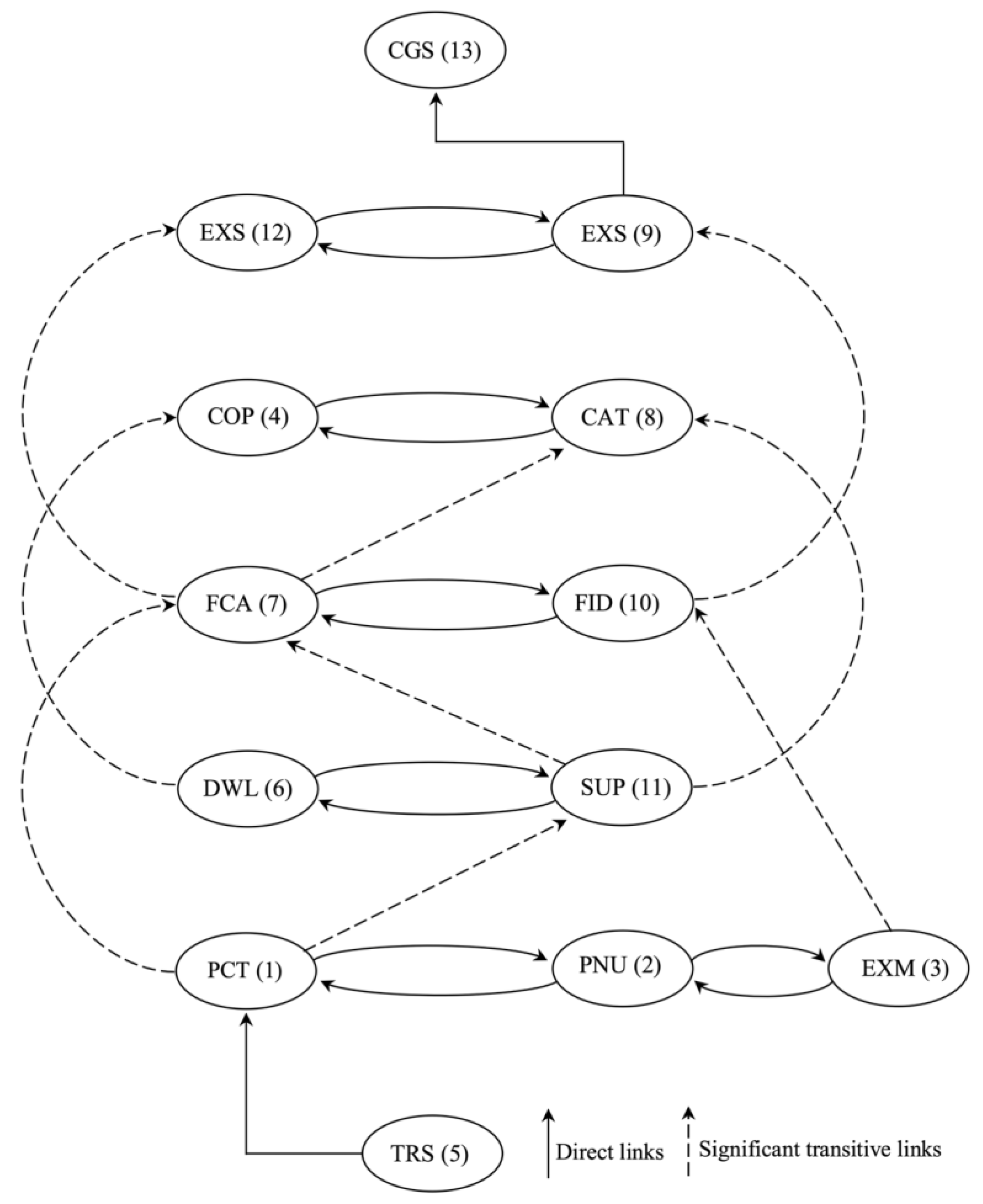

4.3. Structural Model

4.4. TISM of MICMAC Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theory Implications

5.2. Practice Implications

5.3. Limitations and Further Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tangchonlatip, K.; Chamratrithirong, A.; Lucktong, A. The potential for civic engagement of older persons in the aging society of Thailand. J. Health Res. 2019, 33, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamom, J.; Ruchiwit, M.; Hain, D. Strategies of repositioning for effective pressure ulcer prevention in immobilized patients in home-based palliative care: An integrative literature reviews. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2020, 103, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkantrakorn, K.; Suksasunee, D. Clinical, electrodiagnostic, and outcome correlation in ALS patients in Thailand. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 43, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyanrattakorn, S.; Chang, C.L. Long-term care (LTC) policy in Thailand on the homebound and bedridden elderly happiness. Health Policy Open 2021, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Seo, J. Analysis of caregiver burden in palliative care: An integrated review. Nurs. For. 2019, 54, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.Y.; Lu, H.L.; Tsai, Y.F. Caregiver burden and health-related quality of life among primary family caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study. Qual. Life. Res. 2020, 29, 2745–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del-Pino-Casado, R.; Cardosa, M.R.; López-Martínez, C.; Orgeta, V. The association between subjective caregiver burden and depressive symptoms in carers of older relatives: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tramonti, F.; Bonfiglio, L.; Bongioanni, P.; Belviso, C.; Fanciullacci, C.; Rossi, B.; Chisari, C.; Carboncini, M.C. Caregiver burden and family functioning in different neurological diseases. Psychol. Health Med. 2019, 24, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialon, L.N.; Coke, S. A study on caregiver burden: Stressors, challenges, and possible solutions. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2012, 29, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yotani, N.; Ishiguro, A.; Sakai, H.; Ohfuji, S.; Fukushima, W.; Hirota, Y. Factor-Associated caregiver burden in medically complex patients with special health-care needs. Pediatr. Int. 2014, 56, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, M.L.; Mello, J.D.A.; Anthierens, S.; Declercq, A.; Durme, T.V.; Cès, S.R. Caring for a frail older person: The association between informal caregiver burden and being unsatisfied with support from family and friends. Age Aging 2019, 48, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pristavec, T.; Luth, E.A. Informal caregiver burden, benefits, and older adult Mortality: A survival analysis. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2020, 75, 2193–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, P.H.; Molina, J.A.D.C.; Teo, K.; Tan, W.S. Paediatric palliative care improves patient outcomes and reduces healthcare costs: Evaluation of a home-based program. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira-Morales, A.; Valencia, L.; Rojas, L. Impact of the caregiver burden on the effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program: A mediation analysis. Palliat. Support Care 2020, 18, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacio, C.; Krikorian, A.; Limonero, J. The influence of psychological factors on the burden of caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: Resiliency and caregiver burden. Palliat. Support Care 2018, 16, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, N.; Liu, J.; Lou, V.W.O. Caring for frail elders with musculoskeletal conditions and family caregivers’ subjective well-being: The role of multidimensional caregiver burden. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 61, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Sousa-Poza, A. Impacts of informal caregiving on caregiver employment, health, and family. Popul. Age 2015, 8, 113–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Unite Nation. World Population Prospect 2019; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_Highlights.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Chiaranai, C.; Chularee, S.; Srithongluang, S. Older people living with chronic illness. Geriatr. Nurs. 2018, 39, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantirat, P.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Rattanathumsakul, T.; Noree, T. Projection of the number of elderly in different health states in Thailand in the next ten years, 2020–2030. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, N.D.; Chasombat, S.; Tanomsingh, S.; Rajataramya, B.; Potempa, K. Public health in Thailand: Emerging focus on non-communicable diseases. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2011, 26, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chamroonsawasdi, K.; Chottanapund, S.; Tunyasitthisundhorn, P.; Phokaewsuksa, N.; Ruksujarit, T.; Phasuksathaporn, P. Development and validation of a questionnaire to assess knowledge, threat and coping appraisal, and intention to practice healthy behaviors related to non-communicable diseases in the Thai population. Behav. Sci. 2017, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nawamawat, J.; Prasittichok, W.; Prompradit, T.; Chatchawanteerapong, S.; Sittisart, V. Prevalence, and characteristics of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in semi-urban communities: Nakhonsawan, Thailand. J. Health Res. 2020, 34, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oechsle, K.; Ullrich, A.; Marx, G.; Benze, G.; Heine, J.; Dickel, L.M.; Zhang, Y.; Wowretzko, F.; Wendt, K.N.; Nauck, F.; et al. Psychological burden in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer at initiation of specialist inpatient palliative care. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Ornstein, K.A.; Kent, E.E. What do family caregivers know about palliative care? Results from a national survey. Palliat. Support Care 2019, 17, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarberg, A.S.; Kvangarsnes, M.; Hole, T.; Thronæs, M.; Madssen, T.S.; Landstad, B.J. Silent voices: Family caregivers’ narratives of involvement in palliative care. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 1446–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Williams-Reade, J.; Lamson, A.L.; Knight, S.M.; White, M.B.; Ballard, S.M.; Desai, P.P. Paediatric palliative care: A review of needs, obstacles, and the future. J. Nurs. Manag. 2015, 23, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jawahri, A.; Greer, J.A.; Pirl, W.F.; Park, E.R.; Jackson, V.A.; Back, A.L.; Kamdar, M.; Jacobsen, J.; Chittenden, E.H.; Rinaldi, S.P.; et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care on caregivers of patients with lung and gastrointestinal cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Oncologist 2017, 22, 1528–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aoun, S.M.; Rumbold, B.; Howting, D.; Bolleter, A.; Breen, L.J. Bereavement support for family caregivers: The gap between guidelines and practice in palliative care. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brogaard, T.; Jensen, A.B.; Sokolowski, I.; Olesen, F.; Neergaard, M.A. Who is the key worker in palliative home care? Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2011, 29, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ho, A.H.Y.; Car, J.; Ho, M.R.; Tan-Ho, G.; Choo, P.Y.; Patinadan, P.V.; Chong, P.H.; Ong, W.Y.; Fan, G.; Tan, Y.P.; et al. A novel Family Dignity Intervention (FDI) for enhancing and informing holistic palliative care in Asia: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, T.; Harding, R. Palliative care in South Asia: A systematic review of the evidence for care models, interventions, and outcomes. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Radbruch, L.; Lima, L.D.; Knaul, F.; Wenk, R.; Ali, Z.; Bhatnaghar, S.; Blanchard, C.; Bruera, E.; Buitrago, R.; Burla, C.; et al. Redefining palliative care: A new consensus-based definition. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerger, M.; Greer, J.A.; Jackson, V.A.; Park, E.R.; Pirl, W.F.; El-Jawahri, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Hagan, T.; Jacobsen, J.; Perry, L.M.; et al. Defining the elements of early palliative care that are associated with patient-reported outcomes and the delivery of end-of-life care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1096–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, B.V.; Sand, A.M.; Rosland, J.H.; Førland, O. Experiences, and challenges of home care nurses and general practitioners in home-based palliative care-A qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2018, 17, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morey, T.; Scott, M.; Saunders, S.; Varenbut, J.; Howard, M.; Tanuseputro, P.; Webber, C.; Killackey, T.; Wentlandt, K.; Zimmermann, C.; et al. Transitioning from hospital to palliative care at home: Patient and caregiver perceptions of continuity of care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, J.K.; Herbert, A.R.; Heussler, H.S. Paediatric palliative care and intellectual disability-A unique context. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 30, 1111–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.Y.M.; Wong, F.K.Y. Effects of a home-based palliative heart failure program on quality of life, symptom burden, satisfaction, and caregiver burden: A randomized controlled trial. J. Pain Sympt. Manag. 2018, 55, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, T.; Molassiotis, A.; Tan, J.Y.; Chung, B.P.M.; Huang, H.Q. Prevalence and correlates of unmet palliative care needs in dyads of Chinese patients with advanced cancer and their informal caregivers: A cross-sectional survey. Support Care Cancer 2021, 29, 1683–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubaidi, Z.S.A.; Ariffin, F.; Oun, C.T.C.; Katiman, D. Caregiver burden among informal caregivers in the largest specialized palliative care unit in Malaysia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 186. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, A.P.; Buckley, M.M.; Cryan, J.F.; Chorcoráin, A.N.; Dinan, T.G.; Kearney, P.M.; O’Caoimh, R.; Calnan, M.; Clarke, G.; Molloy, D.W. Informal caregiving for dementia patients: The contribution of patient characteristics and behaviors to caregiver burden. Age Ageing 2019, 49, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, W.; Tolson, D.; Jackson, G.A.; Costa, N. A cross-sectional study of family caregiver burden and psychological distress linked to frailty and functional dependency of a relative with advanced dementia. Dementia 2020, 19, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kayaalp, A.; Page, K.J.; Rospenda, K.M. Caregiver burden, work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and mental health of caregivers: A mediational longitudinal study. Work Stress 2021, 35, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.; You, E.; Tatangelo, G. Hearing their voice: A systematic review of dementia family caregivers’ needs. Gerontologist 2016, 56, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, B.T.; Berman, R.; Lau, D.T. Formal and informal support of family caregivers managing medications for patients who receive end-of-life care at home: A cross-sectional survey of caregivers. Palliat. Med. 2014, 28, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limpawattana, P.; Theeranut, A.; Chindaprasirt, J.; Sawanyawisuth, K.; Pimporm, J. Caregivers burden of older adults with chronic illnesses in the community: A cross-sectional study. J. Community Health 2013, 38, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajay, S.; Kasthuri, A.; Kiran, P.; Malhotra, R. Association of impairments of older persons with caregiver burden among family caregivers: Findings from rural South India. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 68, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, J.; Muers, J.; Patterson, T.G.; Marczak, M. Self-Compassion, coping strategies, and caregiver burden in caregivers of people with dementia. Clin. Gerontol. 2019, 42, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, D.Y.P.; Chan, H.Y.L.; Chiu, P.K.C.; Lo, R.S.K.; Lee, L.L.Y. Source of social support and caregiving self-efficacy on caregiver burden and patient’s quality of life: A path analysis on patients with palliative care needs and their caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lethin, C.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Bleijlevens, M.H.; Stephan, A.; Martin, M.S.; Nilsson, K.; Nilsson, C.; Zabalegui, A.; Karlsson, S. Predicting caregiver burden in informal caregivers caring for persons with dementia living at home—A follow-up cohort study. Dementia 2020, 19, 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulek, Z.; Baykal, D.; Erturk, S.; Bilgic, B.; Hanagasi, H.; Gurvit, I.H. Caregiver burden, quality of life and related factors in family caregivers of dementia patients in Turkey. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 41, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konerding, U.; Bowen, T.; Forte, P.; Karampli, E.; Malmström, T.; Pavi, E.; Torkki, P.; Graessel, E. Do caregiver characteristics affect caregiver burden differently in different countries? Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Demen. 2019, 34, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warfield, J.N. Developing interconnection matrices in structural modeling. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man. Cyber 1974, 4, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agarwal, A.; Shankar, R.; Tiwari, M.K. Modeling agility of supply chain. Indust. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.H. Interpretive structural modeling–A useful tool for technology assessment? Technol. Forec. Soc. Chan. 1978, 11, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.D.; Sushil, K.B.; Gupta, A.D. A structural approach to the analysis of causes of system waste in the Indian economy. Syst. Res. 1994, 11, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiyazhagan, K.; Govindan, K.; NoorulHaq, A.; Geng, Y. An ISM approach for the barrier analysis in implementing green supply chain management. J. Clean. Produc. 2013, 47, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attri, R.; Dev, N.; Sharma, V. Interpretive structural modeling (ISM) approach: An overview. Res. J. Manag. Sci. 2013, 2, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sushil. How to check the correctness of total interpretive structural models? Ann. Oper. Res. 2018, 270, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushil. Interpreting the interpretive structural model. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2012, 13, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.D.; Kant, R. Knowledge management barriers: An interpretive structural modeling approach. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. Manag. 2008, 3, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.K. Concepts in caregiver research. J. Nurs. Schol. 2003, 35, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polacsek, M.; Boardman, G.; McCann, T.V. Paying patient and caregiver research participants: Putting theory into practice. J. Advan. Nurs. 2017, 73, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P.; Trauer, T.; Kelly, B.; O’Connor, M.; Thomas, K.; Summers, M.; Zordan, R.; White, V. Reducing the psychological distress of family caregivers of home-based palliative care patients: Short-Term effects from a randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.P.; Huang, S.J.; Tsao, L.I. The life experiences among primary family caregivers of home-based palliative care. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2020, 37, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastawrous, M. Caregiver burden—A critical discussion. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, V.J.; Killian, M.O.; Fields, N. Caregiver identity theory and predictors of burden and depression: Findings from the REACH II study. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassola, B.; Cilluffo, S.; Lusignani, M. Going inside the relationship between caregiver and care-receiver with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Italy, a grounded theory study. Health Soc. Care Comm. 2021, 29, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halinski, M.; Duxbury, L.; Stevenson, M. Employed caregivers’ response to family-role overload: The role of control-at-home and caregiver type. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekdemir, A.; Ilhan, N. Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of bedridden patients. J. Nurs. Res. 2019, 27, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Heffernan, C.; Tan, J. Caregiver burden: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 7, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanhan, A.; Strack, R.W. Online photovoice to explore and advocate for Muslim biopsychosocial spiritual wellbeing and issues: Ecological systems theory and ally development. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 2010–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajuria, G.; Read, S.; Priest, H.M. Using photovoice as a method to engage bereaved adults with intellectual disabilities in research: Listening, learning and developing good practice principles. Adv. Ment. Health Intell. Disab. 2017, 11, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanhan, A.; Arslan, G.; Yavuz, K.F.; Young, J.S.; Çiçek, İ.; Akkurt, M.N.; Ulus, İ.Ç.; Görünmek, E.; Demir, R.; Kürker, F.; et al. A constructive understanding of mental health facilitators and barriers through Online Photovoice (OPV) during COVID-19. ESAM Ekon. Sos. Araştırmalar Dergisi. 2021, 2, 214–249. [Google Scholar]

- Capous-Desyllas, M.; Perez, N.; Cisneros, T.; Missari, S. Unexpected caregiving in later Life: Illuminating the narratives of the resilience of grandmothers and relative caregivers through photovoice methodology. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2020, 63, 262–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID | CGG | CGA | MS | ED | Underlying | CD | Relationship | Income Adequacy | Medical Welfare |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 61 | Married | ES | Yes | 2 months | Spouse | Yes | – |

| 2 | Female | 44 | Single | ES | Yes | 8 months | Son/daughter | No | UC |

| 3 | Male | 49 | Married | ES | Yes | 5 months | Son/daughter | Yes | UC |

| 4 | Male | 53 | Single | ES | Yes | 5 months | Son/daughter | Yes | UC |

| 5 | Female | 34 | Married | ES | Yes | 3 months | Son/daughter | Yes | UC |

| 6 | Female | 37 | Single | Diploma | Yes | 6 months | Son/daughter | No | – |

| 7 | Female | 53 | Married | BA | Yes | 10 months | Spouse | No | – |

| 8 | Female | 47 | Single | BA | Yes | 3 months | Son/daughter | Yes | – |

| 9 | Male | 70 | Married | BA | Yes | 1 months | Spouse | Yes | CSMBS |

| 10 | Female | 36 | Married | BA | Yes | 8 months | Son/daughter | Yes | CSMBS |

| 11 | Female | 37 | Single | – | Yes | 5 months | Son/daughter | No | CSMBS |

| 12 | Female | 47 | Married | HS | Yes | 2 months | Son/daughter | Yes | CSMBS |

| 13 | Female | 61 | Married | Diploma | Yes | 6 months | Spouse | No | UC |

| 14 | Male | 59 | Married | HS | Yes | 2 months | Spouse | Yes | – |

| 15 | Male | 59 | Married | ES | Yes | 3 months | Spouse | Yes | CSMBS |

| 16 | Female | 44 | Widow | ES | Yes | 5 months | Brother/sister | Yes | CSMBS |

| 17 | Male | 52 | Widow | ES | Yes | 2 months | Spouse | Yes | – |

| 18 | Female | 49 | Single | – | Yes | 5 months | Spouse | Yes | – |

| 19 | Male | 58 | Single | – | Yes | 8 months | Spouse | No | CSMBS |

| 20 | Female | 58 | Single | – | Yes | 5 months | Spouse | No | – |

| 21 | Female | 59 | Single | ES | Yes | 8 months | Spouse | Yes | CSMBS |

| 22 | Male | 52 | Widow | ES | Yes | 2 months | Brother/sister | No | CSMBS |

| 23 | Female | 44 | Widow | HS | Yes | 6 months | Son/daughter | Yes | – |

| 24 | Female | 39 | Single | Diploma | Yes | 2 months | Son/daughter | No | – |

| 25 | Female | 40 | Married | ES | Yes | 2 months | Son/daughter | Yes | CSMBS |

| 26 | Female | 45 | Married | ES | Yes | 8 months | Son/daughter | Yes | – |

| 27 | Male | 44 | Widow | ES | Yes | 2 months | Son/daughter | Yes | CSMBS |

| 28 | Male | 62 | Widow | – | Yes | 7 months | Spouse | No | UC |

| 29 | Female | 44 | Single | ES | Yes | 7 months | Son/daughter | Yes | CSMBS |

| 30 | Male | 61 | Widow | – | Yes | 5 months | Spouse | No | CSMBS |

| Theme | Issue | Interview Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Palliative care | Palliative care background Palliative care experience | Could you please describe your caregiving history from your experience with palliative care? |

| Palliative care problems | What are the most important problems associated with palliative care? | |

| Primary caring Perform nursing Extrinsic monitoring Complication prevention | What could help you in primary caring, perform nursing, extrinsic monitoring, and complication prevention for treatment in palliative care? | |

| Informal caregiver burden | Caregiver role Caregivers daily task Taking responsibility | What are the most important aspects important aspects of caregivers’ roles, daily activities, and responsibilities? |

| Daily workload Follow-up caring Caring task | What is your daily workload, follow-up caring, and caring tasks associated with caregiver burden? | |

| Caregiving strain Financial distress Support of patient External support | How does your caregiving strain, financial distress, support of the patient, and external support make you feel burdened for caring? | |

| Caregiving strategy | Can you share with us your caregiving strategy for caring for an elderly patient in your family? |

| Theme | Enables | Acronym | Respondents Confirmed | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | Time 2 | ||||

| Palliative care | Primary caring treatment | PCT (1) | √ | √ | 28 (93.33) |

| Performing nursing | PNU (2) | √ | √ | 27 (90) | |

| Extrinsic monitoring | EXM (3) | √ | √ | 30 (100) | |

| Complication prevention | COP (4) | √ | √ | 30 (100) | |

| Informal caregiver burden | Taking responsibility | TRS (5) | √ | √ | 30 (100) |

| Daily workload | DWL (6) | √ | √ | 30 (100) | |

| Follow-up caring | FCA (7) | √ | √ | 26 (86.66) | |

| Caring task | CAT (8) | √ | √ | 30 (100) | |

| Caregiving strain | CVS (9) | √ | √ | 25 (83.33) | |

| Financial distress | FID (10) | √ | √ | 24 (80) | |

| Support of patient | SUP (11) | √ | √ | 30 (100) | |

| External support | EXS (12) | √ | √ | 21 (70) | |

| Caregiving strategy | CGS (13) | √ | √ | 29 (96.66) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | * | * | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | * | * | – | * | * |

| 2 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | – |

| 3 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 4 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 5 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 6 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 7 | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | * | * |

| 8 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 9 | – | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | – |

| 10 | * | * | – | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | – | * | * | * |

| 11 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 12 | * | * | * | – | * | * | – | – | * | * | – | * | * | * | – |

| 13 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| (16) | (17) | (18) | (19) | (20) | (21) | (22) | (23) | (24) | (25) | (26) | (27) | (28) | (29) | (30) | |

| 1 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 2 | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * |

| 3 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 4 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 5 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 6 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 7 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | * | * | * | – |

| 8 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 9 | – | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | * | * | * | – | * | * |

| 10 | * | * | – | * | * | * | *– | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | * |

| 11 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 12 | * | – | * | – | – | * | * | – | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| 13 | * | * | * | * | * | – | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| IFCB Descriptions | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | X | V | X | X | X | X | X | X | V | V | V | V | V |

| 2 | X | V | V | V | O | X | O | O | V | O | V | O | V |

| 3 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| 4 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | V | V | O | V |

| 5 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | O | V | V |

| 6 | X | X | X | V | X | X | V | X | V | O | O | O | X |

| 7 | V | X | X | V | X | V | V | V | X | O | X | O | X |

| 8 | X | X | X | O | X | X | V | X | V | O | V | O | O |

| 9 | X | X | X | O | O | O | O | X | X | V | X | O | V |

| 10 | O | O | O | O | X | O | O | O | X | V | X | O | O |

| 11 | O | O | O | O | O | O | V | X | X | V | X | X | O |

| 12 | X | V | X | X | O | O | V | O | O | O | O | X | X |

| 13 | X | X | X | V | O | O | X | O | O | O | O | X | X |

| Enables | IFCB of Caring for CIBEPs | Driving Power | Rank | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 13 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 2 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 2 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 4 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 3 |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 5 |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 7 |

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 |

| Dependence power | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 10 | ||

| IFCB | Reachability Set | Antecedent Set | Intersection Set | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 | 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 13 | 1 |

| 2 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 11, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 11, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 11, 13 | 5 |

| 3 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 | 1 |

| 4 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 | 2 |

| 5 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13 | 2 |

| 6 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13 | 4 |

| 7 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13 | 3 |

| 8 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11 | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11 | 5 |

| 9 | 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 | 5 |

| 10 | 5, 9, 10, 11 | 5, 9, 10, 11 | 5, 9, 10, 11 | 7 |

| 11 | 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 | 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 | 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 | 6 |

| 12 | 3, 5, 12, 13 | 3, 5, 12, 13 | 3, 5, 12, 13 | 7 |

| 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 12, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 12, 13 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 12, 13 | 6 |

| IFCB Descriptions | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | Driving Power | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 * | 1 * | 1 * | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 2 |

| 2 | 1 * | 1 | 1 * | 1 | 1 | 1 * | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 2 |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1* | 1 * | 1 * | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 2 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 * | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 |

| 5 | 1 * | 1* | 1 * | 1 * | 1 | 1 * | 1 * | 1 * | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 1 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 * | 1 | 1 * | 1 | 1 * | 1 * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 3 |

| 7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 * | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 4 |

| 8 | 1 * | 0 | 1 * | 1 | 1 * | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 * | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 6 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 * | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 4 |

| 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 3 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 * | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 6 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 1 * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Dependence power | 9 | 4 | 13 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 6 |

| IFCB | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | 0 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mamom, J.; Daovisan, H. Listening to Caregivers’ Voices: The Informal Family Caregiver Burden of Caring for Chronically Ill Bedridden Elderly Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010567

Mamom J, Daovisan H. Listening to Caregivers’ Voices: The Informal Family Caregiver Burden of Caring for Chronically Ill Bedridden Elderly Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010567

Chicago/Turabian StyleMamom, Jinpitcha, and Hanvedes Daovisan. 2022. "Listening to Caregivers’ Voices: The Informal Family Caregiver Burden of Caring for Chronically Ill Bedridden Elderly Patients" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010567

APA StyleMamom, J., & Daovisan, H. (2022). Listening to Caregivers’ Voices: The Informal Family Caregiver Burden of Caring for Chronically Ill Bedridden Elderly Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010567