What Are the Common Themes of Physician Resilience? A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

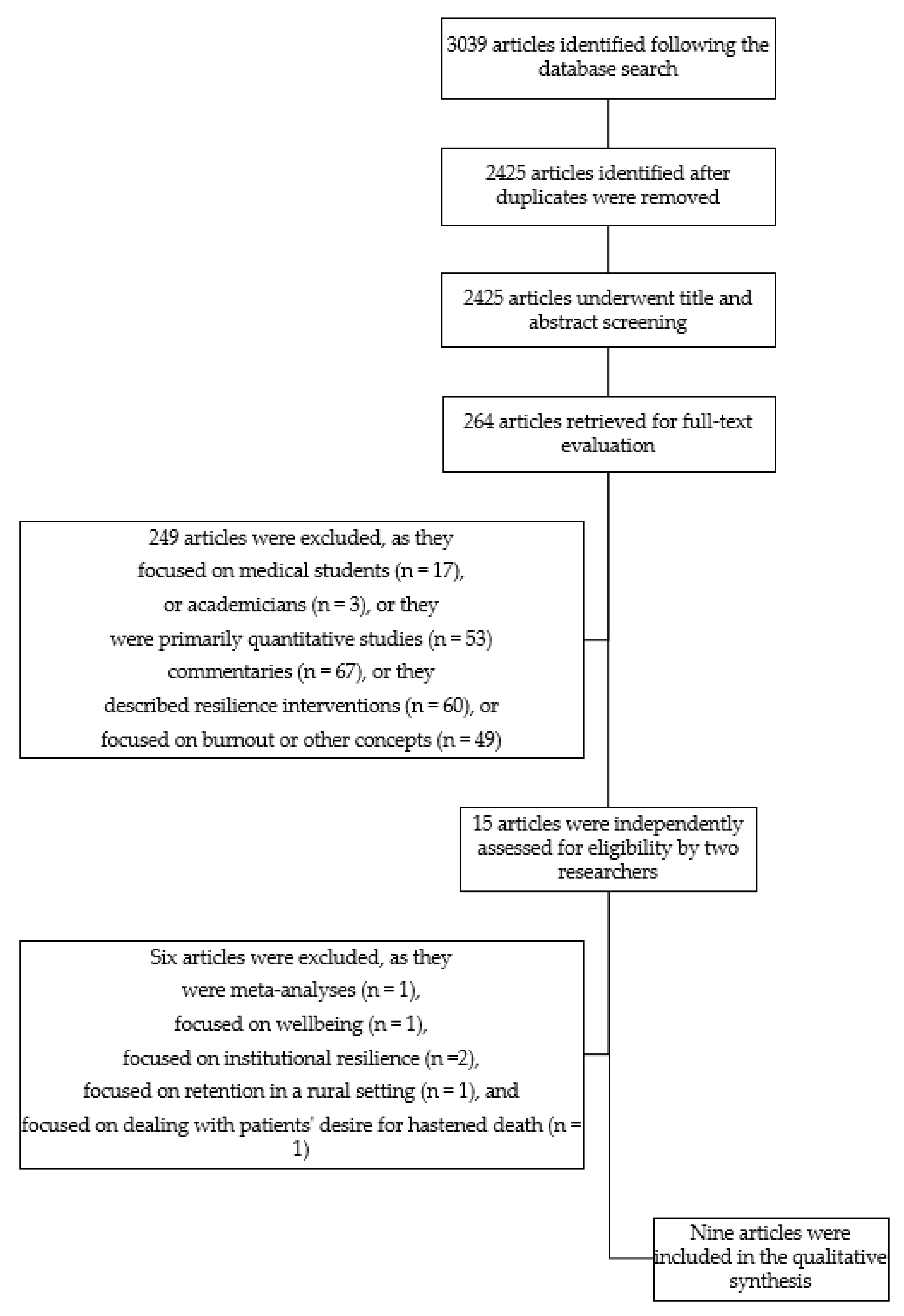

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Study Descriptions

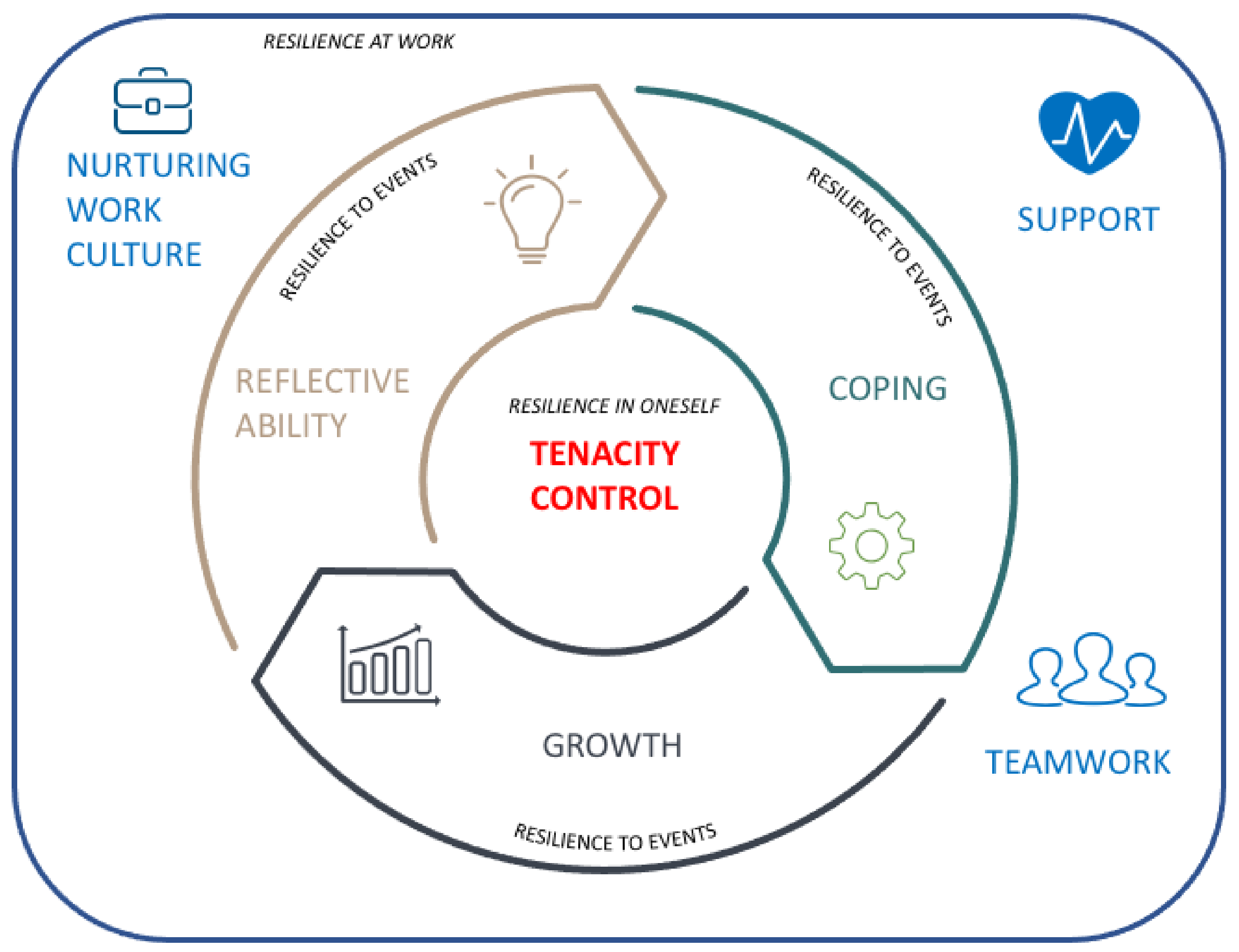

3.2. Themes of Physician Resilience

3.2.1. Theme 1: Tenacity

Aspiration

“I can’t think of anything else that I would rather be doing.” [39]

“...what is more intimate that being in the room and delivering somebody’s baby…we appreciate how intimate that moment is, and how special it is to get to be a part of it.” [24].

“There are patients that you see that you think, “Oh dear, it’s so-and-so again” and you say to yourself, that this is a person who’s got rights, who is doing their best to live their life by their own values, their own circumstances, and you start to see the good in them, you start to see their achievements, their essential humanity.” [40].

Commitment

“My favorite, which happens when nobody’s looking, is when the patient says, ‘Can I come back and see you? You’re so good. Thank you so much. That was the first time somebody’s explained this to me.” [24].

3.2.2. Theme 2: Resources

Support

“It’s important to find the right balance between self-overestimation and a lack of self-confidence. You need an environment of family and friends who will tell you when you start behaving badly. My wife is my severest critic.” [21].

Teamwork

“How your day is structured, how everybody works together, and that I think creates a much more resilient work force in terms of the practice but also individually, it reinforces your own resilience.” [41].

Institutional Culture

“... seeing the patients is a piece of cake, the bureaucracy around seeing them is unbelievable.” [42].

“...the hardest part of residency is you go from 20-plus years of being in school where you get a gold star, you get an A, you get these pats on the back. In clinical work, where these rewards are not always visible, the residents can get discouraged. During residency, ‘This is just the expectation, this is what you’re doing, this is a job’ and there’s no one to be like, ‘Wow, that was a great job you did today.” [24].

3.2.3. Theme 3: Control

Professional Boundaries

“Knowing what your role is and sticking to that, I suppose being assertive with other disciplines.” [41].

Acknowledging One’s Own Limitations

“It takes a certain amount of humility to be able to say ‘you know what, I can’t figure this out by myself’ … and there’s nothing wrong with that.” [39].

Work–Life Balance

“I have to look after myself, and I can’t believe how much more productive and energetic I am if I pay attention to that piece.” [39].

3.2.4. Theme 4: Adaptive Coping

“I think there’s an element too,... with resilience that you come across the issue and you’re arrogant enough and confident enough that you can come up with a solution to solve it and to cope with whatever issue it is that comes through the door.” [41].

3.2.5. Theme 5: Reflective Ability

“I regularly ask myself questions like: Where am I right now? Where do I want to go? What do I find uncongenial? Why am I dissatisfied? What can I do to change that? Another good idea is to do this at a particular time. Ask yourself: Where were the perks last year? Where are they this year?” [21].

3.2.6. Theme 6: Growth

“But it’s also looking at things in a kind of positive light, it’s not being drummed down, it’s looking at it as ‘Well I can solve this’, it’s looking at the cup half full I’d say. It’s ‘I can solve this.’ [41].

“Substance abuse is always a difficult area, because you don’t get many cures. But, if you get someone onto methadone and give them out of goal, that might be a success. If you keep someone alive for 5 years longer than they would have otherwise, you get to judge that as a success as well.” [40].

3.3. Line-of-Argument Synthesis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Hasan, O.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; West, C.P. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction with Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1600–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Torre, M.; Ramos, M.A.; Rosales, R.C.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of burnout among physicians a systematic review. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2018, 320, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, D.A.; Ramos, M.A.; Bansal, N.; Khan, R.; Guille, C.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Sen, S. Prevalence of Depression and Depressive Symptoms among Resident Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2015, 314, 2373–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyond Blue. National Mental Health Survey of Doctors and Medical Students; Beyond Blue: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Ripoll, M.J.; Meneses-Echavez, J.F.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Fraile-Navarro, D.; Fiol-deRoque, M.A.; Pastor-Moreno, G.; Castro, A.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Zamanillo Campos, R.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C. Impact of viral epidemic outbreaks on mental health of healthcare workers: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagioti, M.; Panagopoulou, E.; Bower, P.; Lewith, G.; Kontopantelis, E.; Chew-Graham, C.; Dawson, S.; Van Marwijk, H.; Geraghty, K.; Esmail, A. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.; Lydon, S.; Byrne, D.; Madden, C.; Connolly, F.; Oconnor, P. A systematic review of interventions to foster physician resilience. Postgrad. Med. J. 2017, 94, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, T.M.; Masten, A.S. Fostering the Future: Resilience Theory and the Practice of Positive Psychology. In Positive Psychology in Practice; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 521–538. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Building Resilience. Harvard Business Review; Joshua Macht: Brighton, CO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Windle, G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 2010, 21, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Dia, M.J.; DiNapoli, J.M.; Garcia-Ona, L.; Jakubowski, R.; O’Flaherty, D. Concept Analysis: Resilience. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2013, 27, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resilience, 3rd ed; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/ (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Howe, A.; Smajdor, A.; Stöckl, A. Towards an understanding of resilience and its relevance to medical training. Med. Educ. 2012, 46, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G.E.; Neiger, B.L.; Jensen, S.; Kumpfer, K.L. The resiliency model. Health Educ. 1990, 21, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, E.E. Risk, resilience, and recovery: Perspectives from the Kauai Longitudinal Study. Dev. Psychopathol. 1993, 5, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, G.E. The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 58, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthar, S.S.; Cicchetti, D.; Becker, B. The Construct of Resilience: A Critical Evaluation and Guidelines for Future Work. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, H.; Stewart, D.E.; Diaz-Granados, N.; Berger, E.L.; Jackson, B.; Yuen, T. What Is Resilience? Can J. Psychiatry 2011, 56, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, H.D.; Elliott, A.M.; Burton, C.; Iversen, L.; Murchie, P.; Porteous, T.; Matheson, C. Resilience of primary healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, e423–e433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwack, J.; Schweitzer, J. If Every Fifth Physician Is Affected by Burnout, What about the other Four? Resilience Strategies of Experienced Physicians. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, R.S.; McKinley, N.; Dempster, M.; Campbell, W.J.; Kirk, S.J. A study of the relationship between resilience, burnout and coping strategies in doctors. Postgrad. Med. J. 2017, 94, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpkin, A.L.; Khan, A.; West, D.C.; Garcia, B.M.; Sectish, T.C.; Spector, N.D.; Landrigan, C.P. Stress from Uncertainty and Resilience among Depressed and Burned out Residents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Acad. Pediatr. 2018, 18, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel, A.F.; Honart, A.W.; Robinson, A.; Jones, A.-A.; Squires, A. Thriving in scrubs: A qualitative study of resident resilience. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, L.S.; Gunst, C.; Blitz, J.; Coetzee, J.F. What keeps health professionals working in rural district hospitals in South Africa? Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2015, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mata, D.A.; Ramos, M.A.; Kim, M.M.; Guille, C.; Sen, S. In their own words: An analysis of the experiences of medical interns participating in a prospective cohort study of depression. Acad. Med. 2016, 91, 1244–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D.; Downe, S. Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: A literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 50, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, K.; Downe, S. Why Do Women Not Use Antenatal Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries? A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, S.; Jensen, L.; Kearney, M.H.; Noblit, G.; Sandelowski, M. Qualitative Metasynthesis: Reflections on Methodological Orientation and Ideological Agenda. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 1342–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadi, M.M.; Nordin, N.I.; Roslan, N.S.; Tan, C.; Yusoff, M.S.B. Reframing Resilience Concept: Insights from a Meta-synthesis of 21 Resilience Scales. Educ. Med. J. 2020, 12, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, N.S.; Yusoff, M.S.B.; Asrenee, A.R.; Morgan, K. What are the common elements of resilience in the physician context: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. PROSPERO 2019, CRD4201912, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, L.A.; Allen, M.N. Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Findings. Qual. Health Res. 1996, 6, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, J.; Booth, A.; Cargo, M.; Flemming, K.; Garside, R.; Hannes, K.; Harden, A.; Harris, J.; Lewin, S.; Pantoja, T.; et al. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series—Paper 1: Introduction. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 97, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noblit, G.W.; Hare, R.D. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Britten, N.; Campbell, R.; Pope, C.; Donovan, J.; Morgan, M.; Pill, R. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: A worked example. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2002, 7, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, L.; Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; Dillon, L. Quality in Qualitative Evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence. 2003. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/190986/Magenta_Book_quality_in_qualitative_evaluation__QQE_.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2018).

- Lewin, S.; Booth, A.; Glenton, C.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Rashidian, A.; Wainwright, M.; Bohren, M.A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Colvin, C.J.; Garside, R.; et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: Introduction to the series. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Seagull, F.J.; Plasters, C.L.; Moss, J.A. Resilience in intensive care units: A transactive responsibility model. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–10 October 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.M.; Karen, T.; Waters, H.; Everson, J. Building physician resilience. Can. Fam. Physician 2008, 54, 722–729. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, A.D.; Phillips, C.B.; Anderson, K.J. Resilience among doctors who work in challenging areas: A qualitative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2011, 61, e404–e410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, C.; Robertson, H.D.; Elliott, A.M.; Iversen, L.; Murchie, P. Resilience of primary healthcare professionals working in challenging environments: A focus group study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, e507–e515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.F.; Croxson, C.H.; Ashdown, H.F.; Hobbs, F.R. GP views on strategies to cope with increasing workload: A qualitative interview study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2017, 67, e148–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper Perenn: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, L.; Pather, M.K. Exploring resilience in family physicians working in primary health care in the Cape Metropole. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2019, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Building Your Resilience; American Psychological Association: Washington, WA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, J.G.; McGuinness, T.M. Resilience: Analysis of the concept. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 1996, 10, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, B.M.; Chaboyer, W.; Wallis, M. Development of a theoretically derived model of resilience through concept analysis. Contemp. Nurse 2007, 25, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoeber, J.; Childs, J.H.; Hayward, J.A.; Feast, A.R. Passion and motivation for studying: Predicting academic engagement and burnout in university students. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.L.; Peterson, C.; Matthews, M.D.; Kelly, D.R. Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roslan, N.S.; Yusoff, M.S.B.; Morgan, K.; Ab Razak, A.; Ahmad Shauki, N.I. Evolution of resilience construct, its distinction with hardiness, mental toughness, work engagement and grit, and implications to future healthcare research. Educ. Med. J. (in press).

- Edward, K.-L. The phenomenon of resilience in crisis care mental health clinicians. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2005, 14, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, R.M.; Krasner, M.S. Physician resilience: What it means, why it matters, and how to promote it. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 301–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planning Division Ministry of Health Malaysia. Human Resources for Health Country Profiles 2015 Malaysia; Ministry of Health: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lockyer, J.; Bursey, F.; Richardson, D.; Frank, J.R.; Snell, L.; Campbell, C.; Collaborators, O.B.O.T.I. Competency-based medical education and continuing professional development: A conceptualization for change. Med. Teach. 2017, 39, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillham, J.E.; Shatté, A.J.; Reivich, K.; Seligman, M.E.P. Optimism, pessimism, and explanatory style. Optimism & pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice. In Optimism & Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S.; Segerstrom, S.C. Optimism. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoni, P.S.; Larrabee, J.H.; Birkhimer, T.L.; Mott, C.L.; Gladden, S.D. Influence of Interpretive Styles of Stress Resiliency on Registered Nurse Empowerment. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2004, 28, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, A.-N.; Martinchek, M.; Pincavage, A.T. A Curriculum to Enhance Resilience in Internal Medicine Interns. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2017, 9, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Rabatin, J.T.; Call, T.G.; Davidson, J.H.; Multari, A.; Romanski, S.A.; Hellyer, J.M.; Sloan, J.A.; Shanafelt, T.D. Intervention to promote physician well-being, job satisfaction, and professionalism a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. An Analysis of Coping in a Middle-Aged Community Sample. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1980, 21, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L.B.; Iglewicz, A.; Moutier, C. A Conceptual Model of Medical Student Well-Being: Promoting Resilience and Preventing Burnout. Acad. Psychiatry 2008, 32, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, E.; O’Connor, P.; Lydon, S.; Mongan, O.; Connolly, F.; Diskin, C.; McLoughlin, A.; Rabbitt, L.; McVicker, L.; Reid-McDermott, B.; et al. Stress, coping, and psychological resilience among physicians. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M. Resilience as a dynamic concept. Dev. Psychopathol. 2012, 24, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S. Coping Theory and Research: Past, Present, and Future. Psychosom. Med. 1993, 55, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, M.; Lee, K.Y.; Tanjung, A.S.; Jelani, I.A.A.; Latiff, R.A.; Razak, H.A.; Shauki, N.I.A. The prevalence of psychological distress and its association with coping strategies among medical interns in Malaysia: A national-level cross-sectional study. Asia-Pac. Psychiatry 2020, 13, e12417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doolittle, B.R.; Windish, D.M.; Seelig, C.B. Burnout, Coping, and Spirituality among Internal Medicine Resident Physicians. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, J.E.; Lemaire, J. Physician Coping Styles and Emotional Exhaustion. Relat. Ind. 2013, 68, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp, K.K.; Stoller, E.P.; Sage, P.; Aikens, J.E. The Effects of Sleep Loss and Fatigue on Resident—Physicians: A Multi-Institutional, Mixed-Method Study. Acad. Med. 2004, 79, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, S.; O’Brien, K.; O’Keeffe, N.; Iomaire, A.N.C.; Kelly, M.E.; McCormack, J.; McGuire, G.; Evans, D.S. Practise what you preach: Health behaviours and stress among non-consultant hospital doctors. Clin. Med. 2016, 16, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotile, W.M.; Fallon, R.S.; Simonds, G.R. Moving From Physician Burnout to Resilience. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 62, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, K.; Makker, V.; Lynch, J.; Banerjee, S. From Burnout to Resilience: An Update for Oncologists. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2018, 38, 862–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkel, A.F.; Robinson, A.; Jones, A.-A.; Squires, A. Physician resilience: A grounded theory study of obstetrics and gynaecology residents. Med. Educ. 2018, 53, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchalik, D.; Goldman, C.C.; Carvalho, F.F.L.; Talso, M.; Lynch, J.H.; Esperto, F.; Pradere, B.; Van Besien, J.; Krasnow, R.E. Resident burnout in USA and European urology residents: An international concern. BJU Int. 2019, 124, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Densen, P. Challenges and Opportunities Facing Medical Education. Trans. Am. Clin. Clim. Assoc. 2011, 122, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Benbassat, J.; Baumal, R.; Chan, S.; Nirel, N. Sources of distress during medical training and clinical practice: Suggestions for reducing their impact. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Horton, J.; Shoimer, I.; Patten, S. Predictors of Well-Being in Resident Physicians: A Descriptive and Psychometric Study. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2015, 7, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, A.J.; Ricotta, D.N.; Freed, J.; Smith, C.C.; Huang, G.C. Adapting Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a Framework for Resident Wellness. Teach. Learn. Med. 2018, 31, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, G.; Rippe, J. Physician Burnout: A Lifestyle Medicine Perspective. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2020, 15, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, R.; Bonney, A. Junior doctors, burnout and wellbeing: Understanding the experience of burnout in general practice registrars and hospital equivalents. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2018, 47, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandarajah, A.P.; Quill, T.E.; Privitera, M.R. Adopting the Quadruple Aim: The University of Rochester Medical Center Experience: Moving from Physician Burnout to Physician Resilience. Am. J. Med. 2018, 131, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, G. Physician burnout. Lancet 2020, 395, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements (Residency); Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: Illinois, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chirico, F. Adjustment Disorder as an Occupational Disease: Our Experience in Italy. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 7, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guille, C.; Speller, H.; Laff, R.; Epperson, C.N.; Sen, S. Utilization and Barriers to Mental Health Services among Depressed Medical Interns: A Prospective Multisite Study. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2010, 2, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobasa, S. Stressful life events, personality and health: An inquiry into hardiness. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Steps | Process | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Getting started | We decided to address the question, “What are the common themes in physician resilience literature?” |

| 2 | Deciding what is relevant to the research question | Based on the question, we set appropriate search terms, criteria, and databases, as shown below. The search terms were checked and refined by the corresponding author’s librarian.Search terms:“resilience” AND (“doctor” OR “physician” OR “intern” OR “trainee” OR “resident” OR “specialist” OR “consultant”)

|

| 3 | Reading the studies | Based on the search results, NSR and KM reviewed all selected papers independently. Any discrepancies were reviewed by MSBY, and the final agreement was achieved by a consensus.We read the full texts of selected papers and appraised the rigor, credibility, and relevance of the individual papers using an 18-item checklist from the Framework for Assessing Qualitative Evaluations [36].In this step, we began to identify the main themes of the selected papers. |

| 4 | Determining how the studies are related | We created a table that included the year of study, participant training stage, sample size, method, and original themes in the primary studies. We then examined the recurring themes across the selected studies. |

| 5 | Translating the studies into one another | Using a grid, we systematically compared the themes across the selected papers to identify a range of themes. To preserve the meaning conveyed by the selected papers, we examined the interpretation of the themes in its original term (first order) and checked for reciprocal translation (similar themes) and refutational translation (disconfirming themes). In order to minimize potential biases that could arise from our beliefs and experiences, we spent time in refutational translation to search for disconfirming themes and discussed the interpretations from various perspectives. |

| 6 | Synthesizing translations | In this step, we formed overarching themes from the reciprocal themes (second order). Related second-order themes were then merged under a broader theme (third order). These second-order and third-order themes were discussed among all the researchers to examine their congruence with the original themes in the selected studies. As the third-order themes are testable interpretations [35], we assessed our confidence in these themes using the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (GRADE-CERQual) [37]. We then developed a line of argument in a statement that summarized the common themes in physician resilience. |

| 7 | Expressing the synthesis | We formed a framework to explain the line of argument in a comprehensible format for potential audiences, such as clinicians, educationists, and policy makers. |

| Authors and Publication Year | Country | Subgroups | Number of Participants | Methods (Approach) | Qualitative Grading * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [38] | United States of America | intensive care unit physicians | 14 | IDI (grounded theory) | C |

| [39] | Canada | general practitioners | 17 | IDI (open inquiry) | B |

| [40] | Australia | doctors working in challenging areas | 15 | IDI (grounded theory) | B |

| [21] | Germany | residents from various specialties | 200 | IDI (mixed-methods study) | A |

| [25] | South Africa | health practitioners working in rural areas | 29 | nominal group technique (not specified) | C |

| [41] | United Kingdom | general practitioners and health professionals | 20 | focus group discussion (inductive approach) | A |

| [26] | United States of America | interns | 103 | free text response (mixed-methods study) | A |

| [42] | United Kingdom | general practitioners | 34 | IDI (modified grounded theory) | A |

| [24] | United States of America | obstetrics and gynecology residents | 18 | IDI (grounded theory) | B |

| Original Themes (First Order) | Subthemes (Second Order) | Final Themes (Third Order) |

|---|---|---|

| pride 1 valuing physician role 2 entering the field 3 personal meaning of work 3 shared purpose 5 value oneself 7 aspirations and values 9 | aspiration | tenacity |

| empathy 1 professionalism 1 altruism 1 culture 1 acceptance and realism 4 interest in the person behind the symptom 4 tolerant 7 connection with patients and work 9 | commitment | |

| personal support 2 cultivation of relations with family and friends 4 support from family, friends or roommates 6 support from significant others 6 support from family and community 9 | support | resource |

| trust/respect 1 quest for and cultivation of contact with colleagues 4 working in a team 5 support from colleague 6 good working relationship / teamwork 7 relationship with medical community 9 | teamwork | |

| resources 1 professional support 2 organizational support 3 institutionalized exchange forums 4 supervision, coaching, psychotherapy 4 culture of support 5 supportive program environment and faculty 6 system-level strategies 8 programming and culture 9 | institutional culture | |

| professional arena 2 locus of control 3 accepting personal boundaries 4 self-demarcation with patients 4 self-demarcation with colleagues 4 self-discipline in connection with diagnosis and information 4 professional boundaries 7 | professional boundaries | control |

| ability to detect gaps 1 self-awareness 2 proactive limitation with the limits of one’s own 4 error management 4 receiving mental health care 6 accept professional limitations 7 attention to self 9 | acknowledging own limitations | |

| personal arena 2 leisure time activity 4 limitation of working hours 4 ritualized time-out period 4 long-time, non-professional field of interest 4 prioritization of basic needs 4 spirituality 4 work-life balance 5 time off work, free time, outside interests, social life 6 exercising and engaging in self-care 6 appreciate humour 6 taking leave 8 | work-life balance | |

| self-organisation 4 talking about job-related stress 4 active engagement with the downside of the medical profession 4 recognizing when change is necessary 4 focus and deal with problems 7 using initiatives 7 anticipate situations, react and deal 7 good organizational skills 7 improving efficiency of working day 8 personal coping strategies 8 effort 9 | adaptive coping | coping |

| personal reflection and goal setting 4 self-awareness and reflexivity 4 creating inner distance by taking an observer perspective 4 appreciating the good things 4 | reflective ability | reflective ability |

| pragmatic markers of success 3 cultivation of one’s own professionalism 4 opportunities for growth 5 optimism 7 flexible and adaptable 7 confidence 7 | growth | growth |

| Themes that Emerged from Meta-Synthesis | Assessment of Methodological Limitations | Assessment of Relevance | Assessment of Coherence | Assessment of Adequacy | Overall Assessment of Confidence * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tenacity 1–5,7,9 | moderate concerns (two studies with moderate limitations) | no concern | minor concerns (data consistent across studies) | moderate concerns (three studies with thin data) | moderate |

| resource 1–9 | high | ||||

| control 1–9 | moderate | ||||

| coping 4,7–9 | minor concerns (one study with minor limitations) | moderate concerns (possible partial relevance-developing countries context) | moderate concerns (data consistent across some studies) | minor concerns (one study with thin data) | moderate |

| reflective ability 4 | no concern | substantial concern (partial relevance as described on one context) | moderate concerns (data consistent within one studies) | no concern | low |

| growth 3–5,7 | minor concerns (one study with minor limitations) | no concern | moderate concerns (data consistent across some studies) | minor concerns (one study with thin data) | moderate |

| Themes Derived from Meta-Synthesis | Potential Physician-Directed Interventions | Potential Organization-Directed Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Tenacity |

|

|

| Resource |

|

|

| Control |

|

|

| Coping |

|

|

| Reflective ability |

|

|

| Growth |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roslan, N.S.; Yusoff, M.S.B.; Morgan, K.; Ab Razak, A.; Ahmad Shauki, N.I. What Are the Common Themes of Physician Resilience? A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010469

Roslan NS, Yusoff MSB, Morgan K, Ab Razak A, Ahmad Shauki NI. What Are the Common Themes of Physician Resilience? A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010469

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoslan, Nurhanis Syazni, Muhamad Saiful Bahri Yusoff, Karen Morgan, Asrenee Ab Razak, and Nor Izzah Ahmad Shauki. 2022. "What Are the Common Themes of Physician Resilience? A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010469

APA StyleRoslan, N. S., Yusoff, M. S. B., Morgan, K., Ab Razak, A., & Ahmad Shauki, N. I. (2022). What Are the Common Themes of Physician Resilience? A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010469