Family Member, Best Friend, Child or ‘Just’ a Pet, Owners’ Relationship Perceptions and Consequences for Their Cats

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Characteristics of Owner and Cat

1.2. Consequences for the Cat’s Living Environment

1.3. Aim of the Study, Theoretical Model, and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Procedure

2.2. Relationship Categories

2.3. Characteristics of the Owner

2.4. Characteristics of the Cat and Living Environment

2.5. Social Behavior of the Cat towards the Owner

2.6. Indicators of the Cat-Owner Relationship

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Response and Sample Description

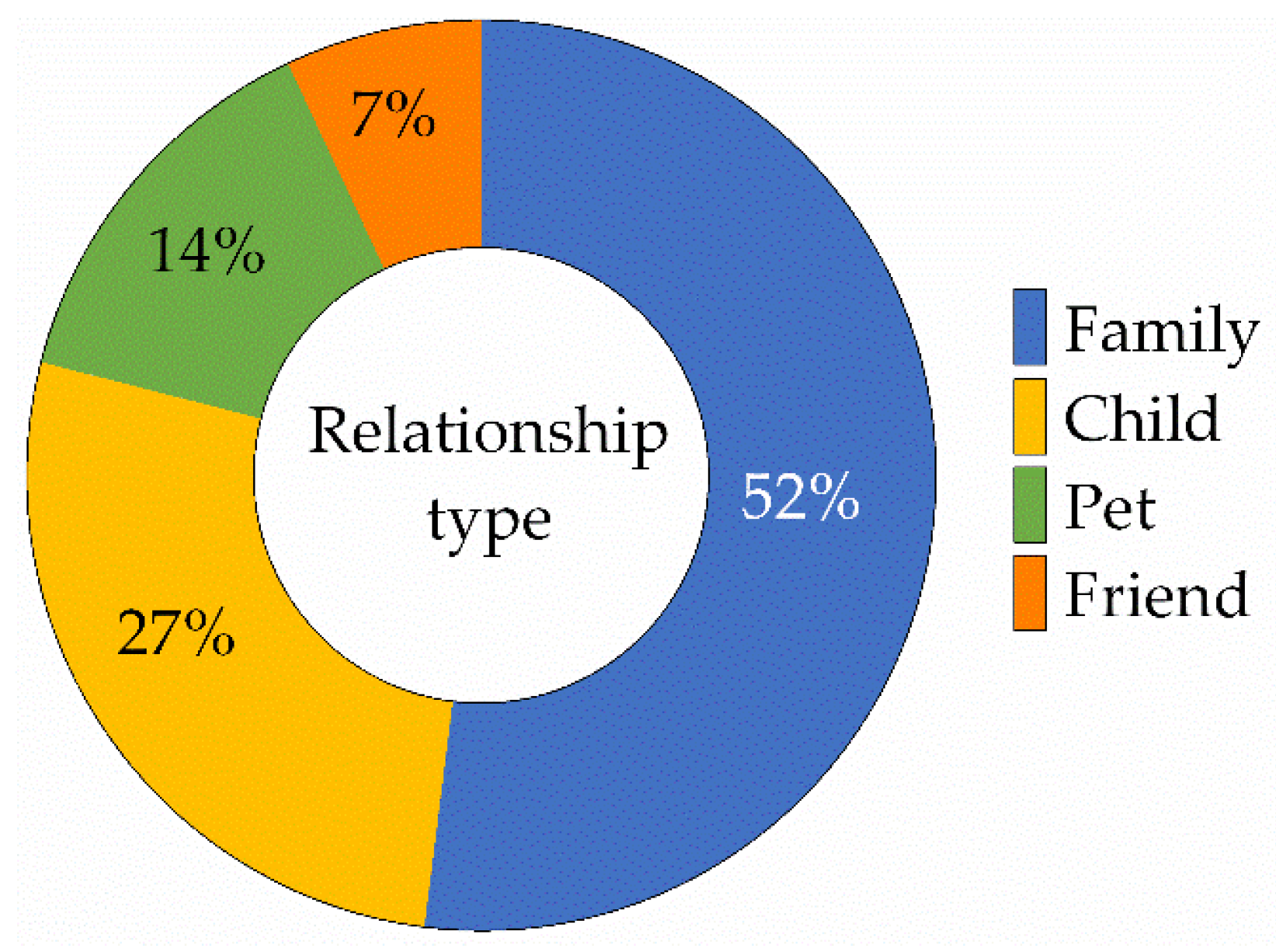

3.2. Relationship Perception

3.3. Determinants for Relationship Perception

Category Differences Regarding Significant Factors

3.4. Consequences for the Cat

3.4.1. Access to the Bedroom

3.4.2. Outdoor Access

3.4.3. Care during Absence

3.4.4. Other Cats in the Household

4. Discussion

4.1. Determinants for Relationship Perception

4.2. Cats as Family Members

4.3. Cats as Children

4.4. Cats as Best Friends

4.5. Cats as ‘Just Pet Animals’

4.6. Living Alone, Loneliness, and the Cats’ Sociocognitive Abilities

4.7. The Danger of Anthropomorphizing the Human–Cat Relationship

4.8. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zasloff, R.L. Measuring attachment to companion animals: A dog is not a cat is not a bird. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1996, 47, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sable, P. Pets, attachment, and well-being across the life cycle. Soc. Work 1995, 40, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stammbach, K.B.; Turner, D.C. Understanding the Human—Cat Relationship: Human Social Support or Attachment. Anthrozoös 1999, 12, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.P. Can pets function as family members? West. J. Nurs. Res. 2002, 24, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hortulanus, R.; Machielse, A.; Meeuwesen, L. Social Isolation in Modern Society, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolkovic, I.; Fajfar, M.; Mlinaric, V. Attachment to pets and interpersonal relationships: Can a four-legged friend replace a two-legged one? J. Eur. Psychol. Stud. 2012, 3, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodsworth, W.; Coleman, G.J. Child–companion animal attachment bonds in single and two-parent families. Anthrozoös 2001, 14, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T.E. Pet Bonding and Pet Bereavement as a Function of Culture and Gender Differences among Adolescents; University of Sarasota: Sarasota, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, N. ‘Animals Just Love You as You Are’: Experiencing Kinship across the Species Barrier. Sociology 2014, 48, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenebaum, J. It’s a dog’s life: Elevating status from pet to “fur baby” at yappy hour. Soc. Anim. 2004, 12, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F. Human-animal bonds I: The relational significance of companion animals. Fam. Process 2009, 48, 462–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans-Wilday, A.S.; Hall, S.S.; Hogue, T.E.; Mills, D.S. Self-disclosure with dogs: Dog owners’ and non-dog owners’ willingness to disclose emotional topics. Anthrozoös 2018, 31, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auster, C.J.; Auster-Gussman, L.J.; Carlson, E.C. Lancaster Pet Cemetery Memorial Plaques 1951–2018: An Analysis of Inscriptions. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsh, E.B.; Turner, D.C. The human-cat relationship. In The Domestic Cat: The Biology of Its Behaviour, 2nd ed.; Turner, D.C., Bateson, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988; pp. 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein, N.L.; Terkel, J. Interrelationships of dogs (Canis familiaris) and cats (Felis catus L.) living under the same roof. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 113, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, C.A.; Menotti-Raymond, M.; Roca, A.L.; Hupe, K.; Johnson, W.E.; Geffen, E.; Harley, E.H.; Delibes, M.; Pontier, D.; Kitchener, A.C.; et al. The Near East origin of cat domestication. Science 2007, 317, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Linseele, V.; van Neer, W.; Hendrickx, S. Evidence for early cat taming in Egypt. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2007, 34, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigne, J.D.; Guilaine, J.; Debue, K.; Haye, L.; Gérard, P. Early taming of the cat in Cyprus. Science 2004, 304, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cafazzo, S.; Natoli, E. The social function of tail up in the domestic cat (Felis silvestris catus). Behav. Processes 2009, 80, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and loss. In Attachment and Loss: Volume II: Separation, Anxiety and Anger; The Hogarth Press: London, UK; The Institute of Psycho-Analysis: London, UK, 1973; pp. 1–429. [Google Scholar]

- Rynearson, E.K. Humans and pets and attachment. Br. J. Psychiatry 1978, 133, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Endenburg, N.; Bouw, J. Motives for acquiring companion animals. J. Econ. Psychol. 1994, 15, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houtte, B.A.; Jarvis, P.A. The role of pets in preadolescent psychosocial development. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 1995, 16, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Stephens, D.L.; Day, E.; Holbrook, S.M.; Strazar, G. A collective stereographic photo essay on key aspects of animal companionship: The truth about dogs and cats. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2001, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hafen, M.; Rush, B.R.; Reisbig, A.M.J.; Mcdaniel, K.Z.; White, M.B. The role of family therapists in veterinary medicine: Opportunities for clinical services, education, and research. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 2007, 33, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, E.; Volsche, S. COVID-19: Companion Animals Help People Cope during Government-Imposed Social Isolation. Soc. Anim. 2021, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arahori, M.; Kuroshima, H.; Hori, Y.; Takagi, S.; Chijiiwa, H.; Fujita, K. Owners’ view of their pets’ emotions, intellect, and mutual relationship: Cats and dogs compared. Behav. Process 2017, 141, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, P.; Enders-Sleegers, M.; Walker, J.K. The emotional lives of companion animals: Attachment and subjective claims by owners of cats and dogs. Anthrozoös 2016, 291, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, E.A.; Portillo, A.J.; Bennett, N.E.; Gray, P.B. Exploring women’s oxytocin responses to interactions with their pet cats. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Veterinary Medical Association. 2001. Available online: https://www.avma.org/one-health/human-animal-bond (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Kummer, H. On the value of social relationships to nonhuman primates: A heuristic scheme. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1978, 17, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders-Slegers, M.J. The meaning of companion animals: Qualitative analysis of the life histories of elderly dog and cat owners. In Companion Animals and Us: Exploring Relationships between People and Pets; Podberscek, A.L., Paul, E.S., Serpell, J.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 237–256. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, J.A. Domestication and history of the cat. In The Domestic Cat: The Biology of Its Behaviour; Turner, D.C., Bateson, P., Bateson, P.P.G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.; Blascovich, J.; Mendes, W.B. Cardiovascular reactivity and the presence of pets, friends, and spouses: The truth about cats and dogs. Psychosom. Med. 2002, 64, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bao, K.J.; Schreer, G. Pets and Happiness: Examining the Association between Pet Ownership and Wellbeing. Anthrozoos 2016, 29, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, A.R.; Lloyd, E.P.; Humphrey, B.T. We Are Family: Viewing Pets as Family Members Improves Wellbeing. Anthrozoos 2019, 32, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.L. The state of research on human–animal relations: Implications for human health. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Serpell, J.A. Jealousy? or just hostility toward other dogs? The risks of jumping to conclusions. Anim. Sentience 2018, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A.; Hecht, J. Looking at dogs: Moving from anthropocentrism to canid umwelt. In Domestic Dog Cognition and Behavior: The Scientific Study of Canis Familiaris; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overall, K.L. Dogs aren’t jealous—they are just asking for accurate information Commentary on Cook et al. on Dog Jealousy. Anim. Sentience 2018, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Koda, N.; Martens, P. How Japanese companion dog and cat owners’ degree of attachment relates to the attribution of emotions to their animals. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McConnell, A.R.; Brown, C.M.; Shoda, T.M.; Stayton, L.E.; Martin, C.E. Friends with benefits: On the positive consequences of pet ownership. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butterfield, M.E.; Hill, S.E.; Lord, C.G. Mangy mutt or furry friend? Anthropomorphism promotes animal welfare. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 957–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, L.; Dijkstra, A. The Psychological Processes Involved in the Development of a High-Quality Relation with one’s Dog. Hum.-Anim. Interact. Bull. 2019, 7, 38–57. [Google Scholar]

- Grigg, E.K.; Kogan, L.R. Owners’ Attitudes, Knowledge, and Care Practices: Exploring the Implications for Domestic Cat Behavior and Welfare in the Home. Animals 2019, 9, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Humphrey, N. Consciousness Regained; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, J.A. Anthropomorphism and Anthropomorphic Selection—Beyond the ‘Cute Response’. Soc. Anim. 2002, 10, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholas, J.; Gilbey, A.; Rennie, A.; Ahmedzai, S.; Dono, J.A.; Ormerod, E. Pet ownership and human health: A brief review of evidence and issues. BMJ 2005, 331, 1252–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podberscek, A.L. Positive and Negative Aspects of Our Relationship with Companion Animals. Vet. Res. Commun. 2006, 30, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallones, L.; Marx, M.B.; Garrity, T.F.; Johnson, T.P. Pet ownership and attachment in relation to the health of US adults, 21 to 64 years of age. Anthrozoös 1990, 4, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N.; Waytz, A.; Akalis, S.; Cacioppo, J.T. When we need a human: Motivational determinants of anthropomorphism. Soc. Cogn. 2008, 26, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dunbar, R.I.M. Bridging the bonding gap: The transition from primates to humans. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2012, 367, 1837–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Geary, D.C.; Flinn, M.V. Evolution of human parental behavior and the human family. Parenting 2001, 1, 5–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M. Sex, attachment, and the development of reproductive strategies. Behav. Brain Sci. 2009, 32, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clutton-Brock, T.H. Review lecture: Mammalian mating systems. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1989, 236, 339–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geary, D.C. Evolution and proximate expression of human paternal investment. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Orians, G.H. On the evolution of mating systems in birds and mammals. Am. Nat. 1969, 103, 589–603. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2459035 (accessed on 9 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Royle, N.J.; Smiseth, P.T.; Kölliker, M. The evolution of parental care. Princet. Guide Evol. 2012, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldous, J. Family Careers: Developmental Change in Families; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, A.; Bulcroft, K. Pets and urban life. Anthrozoös 1987, 1, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, M.C.; Wright, S. The relationship between pet attachment, life satisfaction, and perceived stress: Results from a South African online survey. Anthrozoös 2020, 33, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winefield, H.R.; Black, A.; Chur-Hansen, A. Health effects of ownership of and attachment to companion animals in an older population. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branson, S.M.; Boss, L.; Padhye, N.S.; Gee, N.R.; Trötscher, T.T. Biopsychosocial factors and cognitive function in cat ownership and attachment in community-dwelling older adults. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ines, M.; Ricci-Bonot, C.; Mills, D.S. My Cat and Me—A Study of Cat Owner Perceptions of Their Bond and Relationship. Animals 2021, 11, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, C. Human-cat interactions in the home setting. Anthrozoös 1991, 4, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, G.; Turner, D.C. How Depressive Moods Affect the Behavior of Singly Living Persons Toward their Cats. Anthrozoös 1999, 12, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedl, M.; Bauer, B.; Gracey, D.; Grabmayer, C.; Spielauer, E.; Day, J.; Kotrschal, K. Factors influencing the temporal patterns of dyadic behaviours and interactions between domestic cats and their owners. Behav. Processes 2011, 86, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, M.; Vapalahti, K.; Tiira, K.; Mäki-Tanila, K.; Lohi, H. Breed differences of heritable behaviour traits in cats. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K. Die angeborenen Formen mo¨glicher Erfahrung [The innate forms of potential experience]. Z. Tierpsychol. 1943, 5, 233–519. [Google Scholar]

- Glocker, M.L.; Langleben, D.D.; Ruparel, K.; Loughead, J.W.; Gur, R.C.; Sachser, N. Baby schema in infant faces induces cuteness perception and motivation for caretaking in adults. Ethology 2009, 115, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lobmaier, J.S.; Sprengelmeyer, R.; Wiffen, B.; Perrett, D.I. Female and male responses to cuteness, age and emotion in infant faces. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2010, 31, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foreman-Worsley, R.; Finka, L.R.; Ward, S.J.; Farnworth, M.J. Indoors or Outdoors? An International Exploration of Owner Demographics and Decision Making Associated with Lifestyle of Pet Cats. Animals 2021, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finka, L.R.; Ward, J.; Farnworth, M.J.; Milss, D.S. Owner personality and the wellbeing of their cats share parallels with the parent-child relationship. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, J.; Levine, S. Psychobiology of coping in animals: The effects of predictability. In Coping and Health; Levine, S., Ursin, H., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, S.; Rodan, I.; Carney, H.C.; Heath, S.; Rochlitz, I.; Shearburn, L.D.; Sundahl, E.; Westropp, J.L. AAFP and ISFM feline environmental needs guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2013, 15, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overgaauw, P.A.; van Zutphen, L.; Hoek, D.; Yaya, F.O.; Roelfsema, J.; Pinelli, E.; van Knapen, F.; Kortbeek, L.M. Zoonotic parasites in fecal samples and fur from dogs and cats in The Netherlands. Vet. Parasit. 2009, 163, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, A.; Bulcroft, K. Pets, Families, and the Life Course. J. Marriage Fam. 1988, 50, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.E. Ethnic variations in pet attachment among students at an American school of veterinary medicine. Soc. Anim. 2002, 10, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.C.; Bateson, P.; Bateson, P.P.G. (Eds.) The Domestic Cat: The Biology of Its Behaviour; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBS Statline. Dutch Statistics Database. Available online: https://opendata.cbs.nl/#/CBS/nl/ (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Pongrácz, P.; Szapu, J.S. The socio-cognitive relationship between cats and humans—Companion cats (Felis catus) as their owners see them. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 207, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamelli, S.; Marinelli, L.; Normando, S.; Bono, G. Owner and cat features influence the quality of life of the cat. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 94, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, D.L.; de Moura, R.T.D.; Serpell, J.A. Development and evaluation of the Fe-BARQ: A new survey instrument for measuring behavior in domestic cats (Felis s. catus). Behav. Processes 2017, 141, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Giles-Corti, B.; Bulsara, M. The pet connection: Pets as a conduit for social capital? Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinzie, P.; Stams, G.J.M.; Reijntjes, A.H.A.; Belsky, J. The Relations between Parents’ Big Five Personality Factors and Parenting: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reevy, G.M.; Delgado, M.M. Are emotionally attached companion animal caregivers conscientious and neurotic? Factors that affect the human–companion animal relationship. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2015, 18, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisberg, Y.J.; DeYoung, C.G.; Hirsh, J.B. Gender Differences in Personality across the Ten Aspects of the Big Five. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Worth, D.; Beck, A.M. Multiple ownership of animals in New York City. Trans. Stud. Coll. Physicians Phila. 1981, 3, 280–300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patronek, G.J. Hoarding of animals: An under-recognized public health problem in a difficult-to-study population. Public Health Rep. 1999, 114, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bradshaw, J.W.S. Sociality in Cats: A Comparative Review. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 11, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, P.L.; Strack, M. A game of cat and house: Spatial patterns and behaviour of 14 cats (Felis catus) in the home. Anthrozoos 1996, 9, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, D.; Karagiannis, C.; Zulch, H. Stress—its effects on health and behavior: A guide for practitioners. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2014, 44, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rochlitz, I. Recommendations for the housing of cats in the home, in catteries and animal shelters, in laboratories and in veterinary surgeries. J. Feline Med. Surg. 1999, 1, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, M.E.; Buffington, C.A. Feline focus: Environmental enrichment for indoor cats. Compend. Contin. Educ. Vet. 2010, 32, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, D.C.; Rieger, G.; Gygax, L. Spouses and cats and their effects on human mood. Anthrozoos 2003, 16, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacopoulos, N.M.D.; Pychyl, T.A. An examination of the relations between social support, anthropomorphism and stress among dog owners. Anthrozoös 2008, 21, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, M.; Vonk, J. Man’s other best friend: Domestic cats (F. silvestris catus) and their discrimination of human emotion cues. Anim. Cogn. 2016, 19, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaranta, A.; d’Ingeo, S.; Amoruso, R.; Siniscalchi, M. Emotion Recognition in Cats. Animals 2020, 10, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miklósi, Á.; Pongrácz, P.; Lakatos, G.; Topál, J.; Csányi, V. A comparative study of the use of visual communicative signals in interactions between dogs (Canis familiaris) and humans and cats (Felis catus) and humans. J. Comp. Psychol. 2005, 119, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fugazza, C.; Sommese, A.; Pogány, Á.; Miklósi, Á. Did we find a copycat? Do as I Do in a domestic cat (Felis catus). Anim. Cogn. 2021, 24, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chijiiwa, H.; Takagi, S.; Arahori, M.; Hori, Y.; Saito, A.; Kuroshima, H.; Fujita, K. Dogs and cats prioritize human action: Choosing a now-empty instead of a still-baited container. Anim. Cogn. 2021, 24, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, P.L. The human-cat relationship. In The Welfare of Cats; Rochlitz, I., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 47–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, S.L.H.; Thompson, H.; Guijarro, C.; Zulch, H.E. The influence of body region, handler familiarity and order of region handled on the domestic cat’s response to being stroked. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2015, 173, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueur, C.; Forin-Wiart, M.; Pelé, M. Do They Really Try to Save Their Buddy? Anthropomorphism about Animal Epimeletic Behaviours. Animals 2020, 10, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, L.; Niel, L.; Cheal, J.; Mason, G. Humans can identify cats’ affective states from subtle facial expressions. Anim. Welf. 2019, 28, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, M.C.; Watanabe, R.; Leung, V.S.Y.; Monteiro, B.P.; O’Toole, E.; Pang, D.S.J.; Steagall, P.V. Facial expressions of pain in cats: The development and validation of a feline grimace scale. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ellis, S.L.H.; Swindell, V.; Burman, O.H.P. Human Classification of Context-Related Vocalizations Emitted by Familiar and Unfamiliar Domestic Cats: An Exploratory Study. Anthrozoos 2015, 28, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prato-Previde, E.; Cannas, S.; Palestrini, C.; Ingraffia, S.; Battini, M.; Ludovico, L.A.; Ntalampiras, S.; Prestis, G.; Mattielo, S. What’s in a Meow? A Study on Human Classification and Interpretation of Domestic Cat Vocalizations. Animals 2020, 10, 2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epley, N.; Waytz, A.; Caioppo, J.T. On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 114, 864–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H.A.; Betchart, N.S.; Pittman, R.B. Gender, sex role orientation, and attitude towards animals. Anthrozoös 1991, 4, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, A.C. An Examination of the Relations between Human Attachment, Pet Attachment, Depression, and Anxiety. Doctoral Dissertation, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vidoviæ, V.V.; Stetiæ, V.V.; Bratko, D. Pet Ownership, Type of Pet and Socio-emotional Development of School Children. Anthrozoös 1999, 12, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S. The empathy quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2004, 34, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blouin, D.D. Are Dogs Children, Companions, or Just Animals? Understanding Variations in People’s Orientations toward Animals. Anthrozoös 2013, 26, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Owner Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 1626 | 91% |

| Educational level | ||

| High | 931 | 53% |

| Medium | 613 | 35% |

| Low | 199 | 11% |

| Cat professional | 181 | 10% |

| Age | ||

| <35 yrs. | 555 | 31% |

| 35–55 yrs. | 909 | 50% |

| >55 yrs. | 339 | 19% |

| Social living situation | ||

| Alone | 395 | 22% |

| With 1 other person | 845 | 47% |

| With >1 other person | 563 | 31% |

| Cat characteristics | ||

| Pedigree | 574 | 32% |

| Female | 834 | 46% |

| Neutered | 1646 | 91% |

| Cat as kitten (<3 months) | 754 | 42% |

| First cat | 380 | 21% |

| Factor | Chi-Square | df | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Owner characteristics | ||||

| Gender | 3.70 | 3 | 0.296 | |

| Age | 40.72 | 6 | <0.001 | |

| Educational level | 5.07 | 6 | 0.535 | |

| Cat professional (yes) | 3.63 | 3 | 0.304 | |

| Owner’s social living situation | ||||

| Presence other humans (yes) | 29.57 | 3 | <0.001 | |

| Presence other cats (yes) | 8.31 | 3 | 0.040 | |

| Relationship indicators | ||||

| Company | 19.16 | 12 | 0.085 | |

| Dependency | 38.82 | 12 | <0.001 | |

| Equality | 76.74 | 12 | <0.001 | |

| Empathy | 11.96 | 12 | 0.448 | |

| Loyalty | 22.61 | 12 | 0.031 | |

| Purpose | 16.11 | 12 | 0.186 | |

| Support | 39.34 | 12 | <0.001 | |

| Cat characteristics | ||||

| Cat as kitten (yes) | 2.20 | 3 | 0.532 | |

| Pedigree cat (yes) | 16.44 | 3 | 0.001 | |

| First cat (yes) | 5.24 | 3 | 0.155 | |

| Gender cat (female) | 7.96 | 3 | 0.047 | |

| Cat’s social behavior | ||||

| Allows petting (yes) | 12.21 | 6 | 0.058 | |

| Allows lifting (yes) | 5.64 | 9 | 0.775 | |

| Jumps on lap (yes) | 3.81 | 3 | 0.450 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bouma, E.M.C.; Reijgwart, M.L.; Dijkstra, A. Family Member, Best Friend, Child or ‘Just’ a Pet, Owners’ Relationship Perceptions and Consequences for Their Cats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010193

Bouma EMC, Reijgwart ML, Dijkstra A. Family Member, Best Friend, Child or ‘Just’ a Pet, Owners’ Relationship Perceptions and Consequences for Their Cats. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010193

Chicago/Turabian StyleBouma, Esther M. C., Marsha L. Reijgwart, and Arie Dijkstra. 2022. "Family Member, Best Friend, Child or ‘Just’ a Pet, Owners’ Relationship Perceptions and Consequences for Their Cats" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010193

APA StyleBouma, E. M. C., Reijgwart, M. L., & Dijkstra, A. (2022). Family Member, Best Friend, Child or ‘Just’ a Pet, Owners’ Relationship Perceptions and Consequences for Their Cats. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010193