Barriers and Facilitators for Exclusive Breastfeeding within the Health System and Public Policies from In-Depth Interviews to Primary Care Midwives in Tenerife (Canary Islands, Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

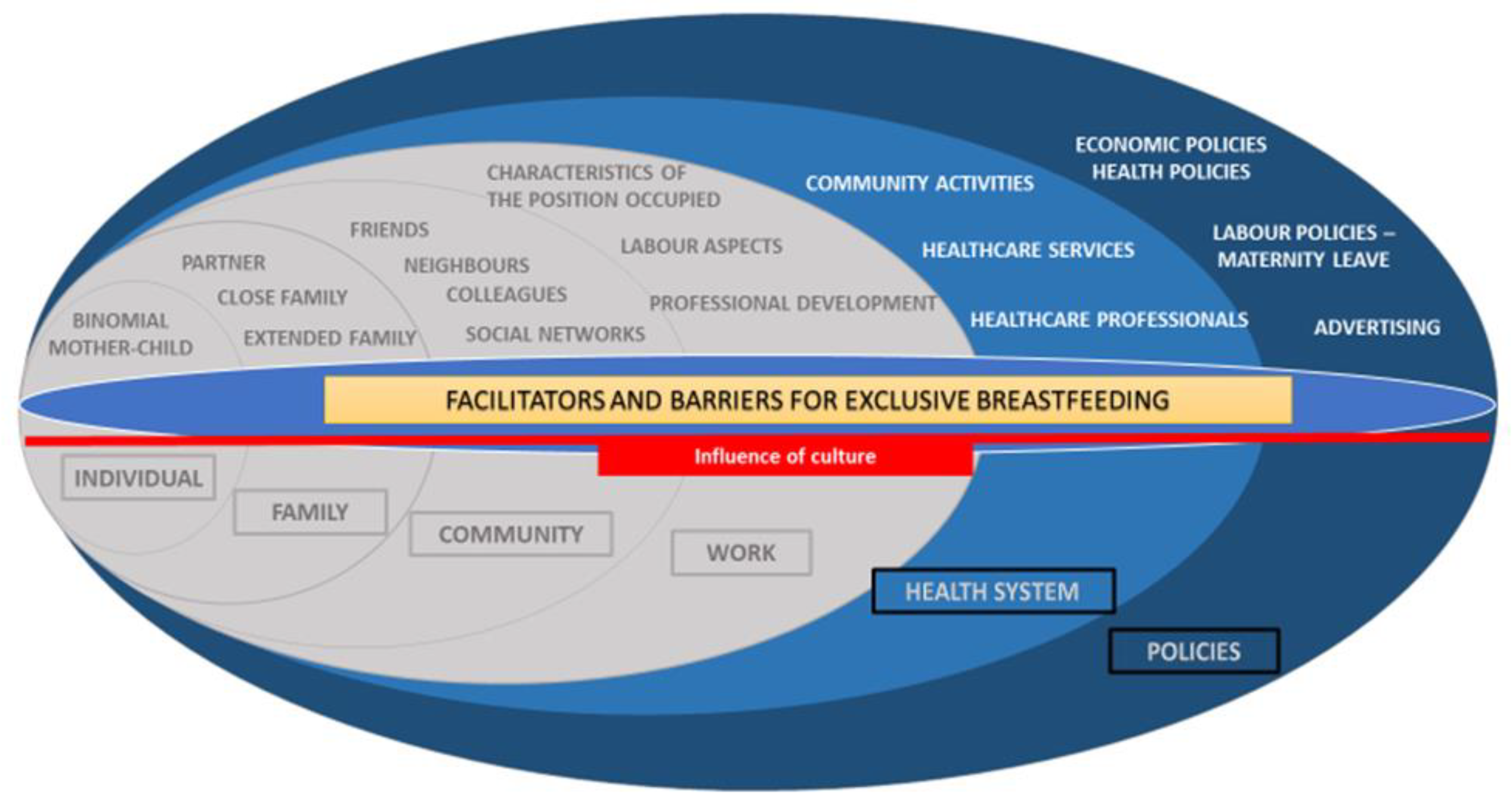

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Analysis

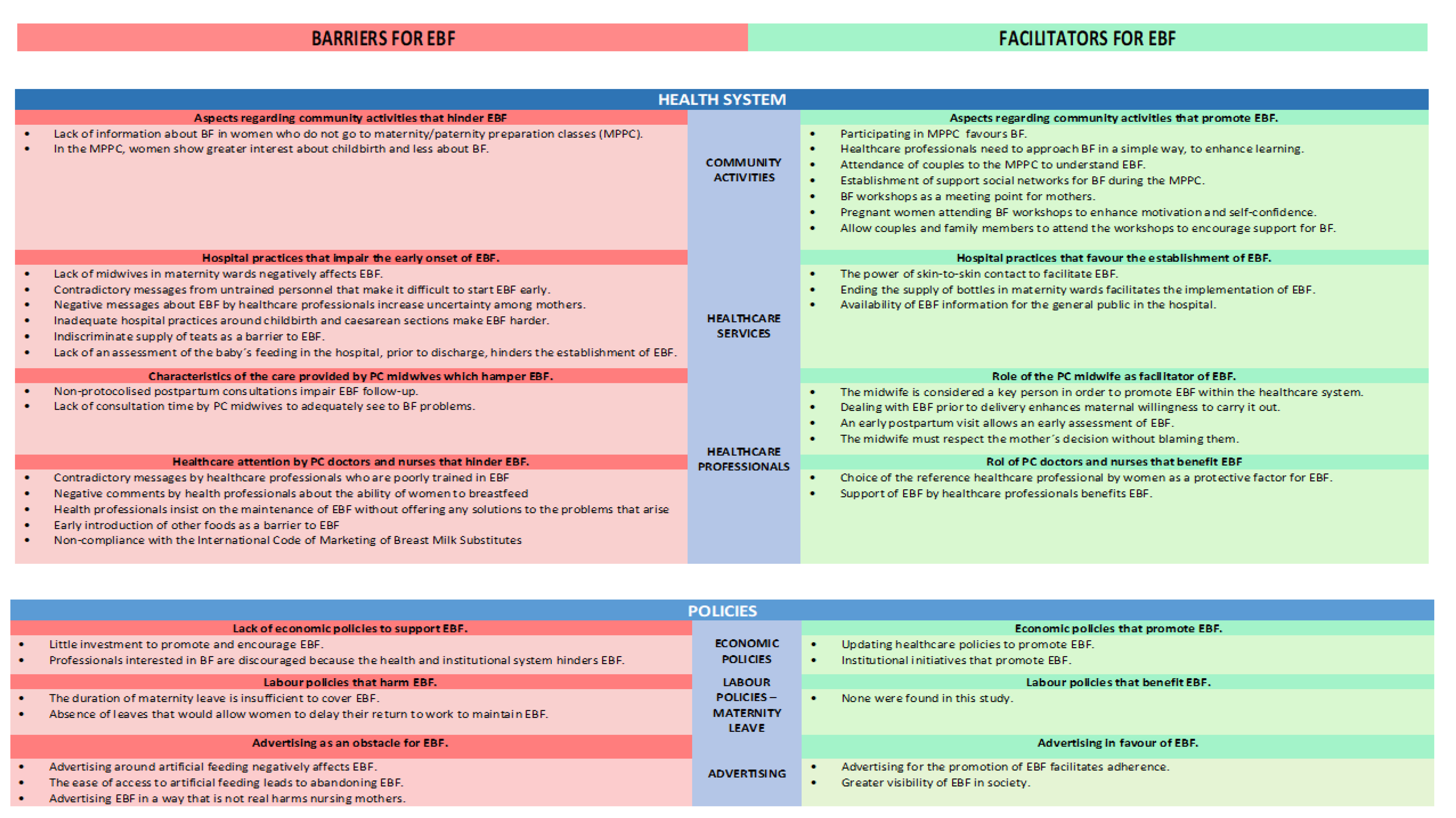

3. Results

3.1. Health System

3.1.1. Role of Community Activities in EBF

Aspects Regarding Community Activities That Hinder EBF

“Those who have had problems with the latching are those who have not come to the maternity preparation classes and who have not learned the proper technique.” (E15)

“I have become convinced that women go to maternal education because the main issue is childbirth. Breastfeeding and the rest is not a priority.” (E7)

Aspects Regarding Community Activities That Promote EBF

“It is positive to talk about breastfeeding during the maternity classes, to give them some basic notions, and very clearly explain to them the things they have to be aware of, particularly regarding the breastfeeding technique.” (E9)

“…give precise information, hassle-free… we should inform in the most natural way, not pressuring.” (E16)

“If the couple has come to maternity education classes, if they have heard about breastfeeding, if they have understood what the milk production mechanism is like, if they are already clear on that, that´s a very important protective factor.” (E5)

“…people start coming to breastfeeding workshops when they have been in the maternity/paternity courses. There, a small women community is created, they interact with each other, a sort of bond is formed.” (E4)

“…breastfeeding groups are a space where you can bring women together, you can observe all feedings and I think it also benefits them psychologically, because they see that many of their problems are shared.” (E9)

“…Women come who have been breastfeeding for two years, others who have been doing it for two months and others who have not given birth yet. So that encourages them a lot… I tell them: look, tell each other the problems you have had, how you started, what happened to you that you almost gave it up.” (E11)

“One learns that the people around the woman are the mainstay of the person and you have to support and involve them. And I’m doing it and it works for me and it’s beautiful, it’s wonderful, it’s very beautiful.” (E3)

3.1.2. Influence of Healthcare Services in EBF

Hospital Practices that Impair the Early Onset of EBF

“…They do not receive enough help from the postpartum wards, because sometimes they come across staff without lactation qualifications, because many wards are still occupied by general nurse practitioners and not by midwives” “… there is strong evidence that the midwife is the professional who has to be in a postpartum ward…” (E9)

“…They always usually comment that, in the first days of being admitted, they can receive different information. They sometimes feel they don´t receive enough help or that they have even doubted things that were clear to them before and thus, miss out on exclusive breastfeeding.” (E4)

“…in the delivery room they are told to put the baby in the crib when they are alone in the room, not to do skin-to-skin contact. Those are the things that lead to insecure mothers.” (E3)

“The more complicated or perhaps more aggressive the delivery is, or less physiological, the more the establishment of breastfeeding is affected.” (E9)

“…many women go home from the hospital with nipple shields that later, when they come to the consultation, are very difficult to get rid of as the child has already gotten used to them…” (E19)

“…typical problems of cracks because there has not been a good assessment of the latching or problems of babies who are not suckling enough, a poorly established breastfeeding which has not been assessed.” (E1)

Hospital Practices that Favour the Establishment of EBF

“The birth plans have been very beneficial; they have encouraged us to have skin-to-skin contact. There is evidence linking successful breastfeeding with skin-to-skin contact and early initiation of breastfeeding.” (E3)

“…as the hospital no longer dispenses bottles so quickly, mothers try a little harder, as before they gave bottles all the time and now they give less…” (E20)

“…I went to visit the delivery room, and on the baby carriages, in the cribs, there were little notes explaining how to interpret hunger cues.” (E3)

3.1.3. The Role of Healthcare Professionals in the Introduction and Maintenance of EBF

The Role of the Midwife in EBF

“More support should be offered in the postpartum, because many times there is a stricter control in the pregnancy, once a month, and then in the postpartum the woman is left a little more neglected, with less control.” (E9)

“…because it is also important for women to be able to consult you, but sometimes you don’t devote all the time you really need, because your schedule is increasingly shortened and you cannot devote all the time the woman would need.” (E14)

“…not being able to be in the same consultation every day makes breastfeeding very difficult, because it is impossible to follow-up on any problem if you are only in a health centre two days a week.” (E18)

“Clinical practice guidelines recognise the midwife as the person in charge of coordinating all actions related to breastfeeding as well as the rest of the team…” (E1)

“It´s also positive, because in Primary Care you generally build confidence with the women and when they trust you, then many times they pay attention to your recommendations.” (E9)

“…before giving birth, we start weaving a web to start putting them in contact with the world of breastfeeding, as her interest at that point in time is not breastfeeding and we have to take that into account.” (E7)

“From their last visit, I already programme their postpartum check-up appointment with them and I tell them: there we will talk about breastfeeding, I will see you as soon as you come back from the hospital, the next day, as there is when you see the problems of breastfeeding.” (E10)

“…us midwives need to clearly accept that there are women who chose not to breastfeed and this is also OK and we must work to not demonise them, we have to free women from that guilt …” (E5)

Role of the Rest of the Professionals in the Primary Care Team in EBF

Role of Primary Care Doctors and Nurses That Benefit EBF

3.2. Policies

3.2.1. Specific Policies and Initiatives Surrounding EBF

Lack of Economic Policies to Support EBF

“I think that from above they are beginning to support projects now… but I believe that breastfeeding has never been supported, neither from above nor from the paediatrician, that is, I believe that breastfeeding doesn’t give money and things that don’t give money don’t have anyone to move them forward”. (E8)

“There are professionals who support breastfeeding and try to lead the way, but they are disappointed because if the leadership does not see the importance of breastfeeding or the broad benefits for the system and the whole of society, if they do not see it, they can’t give it any weight, so they also need training…” (E3)

Economic Policies That Promote EBF

“…I think the Primary Care Management is doing very well because it is promoting breastfeeding and training of professionals in BF which is the basic pillar that affects us. Money is being invested in that…” (E2)

“…I love the initiatives such as the one of a midwife from the Canaries University Hospital because they get to the newspapers, to the public opinion, “be a god mother to a first-time mother”, it’s a precious name that puts breastfeeding on the stage…” (E3)

Labour Policies That Harm EBF

“…There aren’t many laws that really support breastfeeding. You have a maternity leave of 4 months, when they tell you to nurse your baby for 6 months…” (E1)

“What people are trying to do is join all the possible hours of breastfeeding together and return to work as late as possible just when the baby is already eating complementary foods.” (E5)

Advertising as an Obstacle for EBF

“The pharmaceutical industry is very powerful. Perhaps this has a big influence on the promotion and prevention policies not being so strong, because if there is a pharmaceutical company behind with economic interests…” (E9)

“…easy access to artificial milk is negative for breastfeeding, because you go and it is no longer in the pharmacy, it is in the supermarket…” (E6)

“That image of a normal and active woman is missing, even if she´s breastfeeding.” (E3)

Advertising in Favour of EBF

“Regarding advertising, it is true that in recent years there has been a lot of publicity in favour of breastfeeding. It can be seen in many media.” (E9)

“…there is an increasing presence of women breastfeeding on the street and in shopping malls, restaurants. I think society is accepting that part of breastfeeding.” (E7)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of Our Study

4.2. Strengths of Our Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

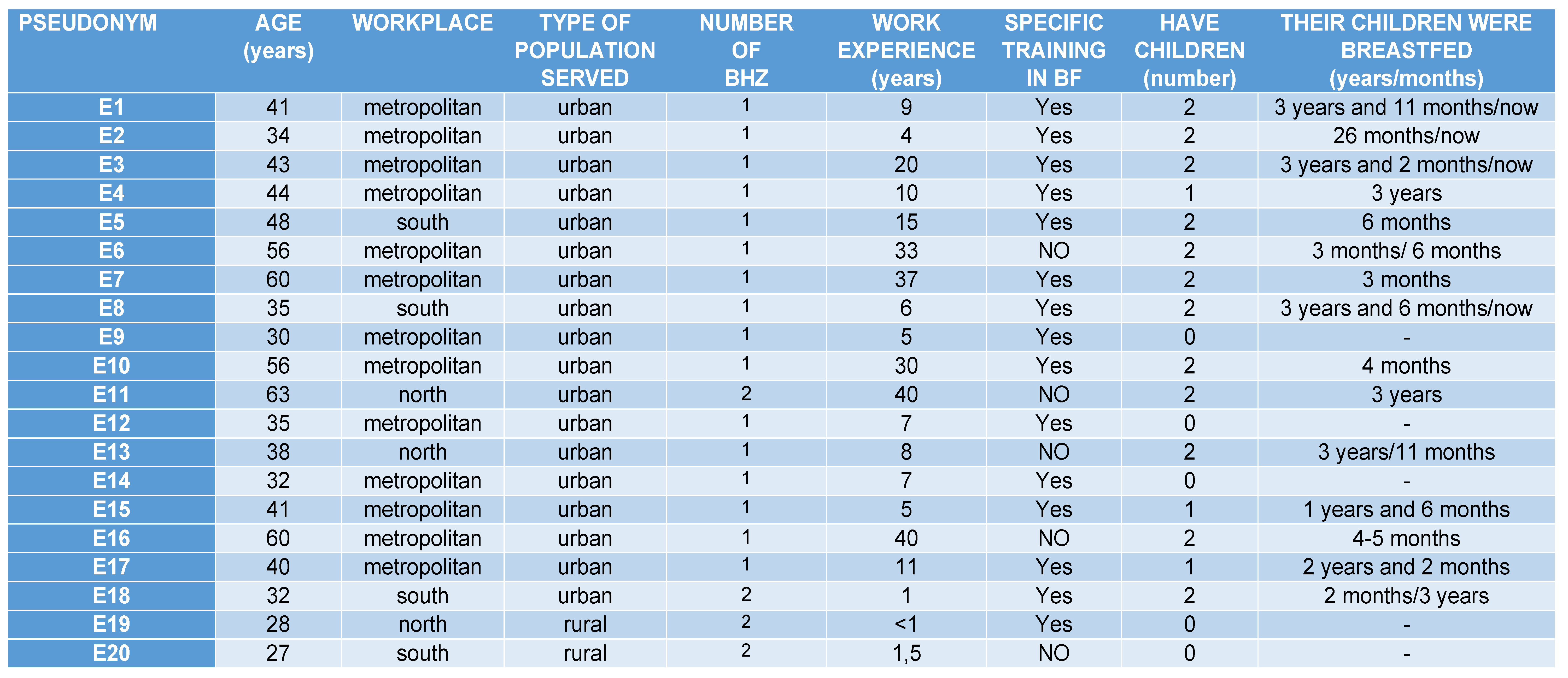

Appendix A. Profiles Primary Care Midwives

Appendix B. Interview Script for Midwives

Appendix B.1. Facilities for Women to Breastfeed

Appendix B.2. Barriers or Obstacles Women Have to Breastfeed

Appendix B.3. Perceptions about the Causes of Breastfeeding Abandonment

Appendix B.4. Perceptions about the Causes of Breastfeeding Adherence

Appendix B.5. Proposal to Improve the Encouragement and Promotion of Adherence to Breastfeeding

Appendix C. Information Sheet and Informed Consent

References

- World Health Organization. Global Nutrition Targets 2025 Breastfeeding Policy Brief; WHO/NMH/NHD/14.7; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Global Nutrition Report 2015: Actions and Accountability to Advance Nutrition and Sustainable Development; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, WA, USA, 2015.

- Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2012. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Disponible. Available online: http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/encuestaNacional/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- WHO. Código Internacional de Comercialización de Sucedáneos de la Leche Materna: Preguntas Frecuentes (Actualización de 2017); Organización Mundial de la Salud: Ginebra, Switzerland, 2017; Licencia: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Comité de Lactancia Materna de la Asociación Española de Pediatría ¿Qué es el Código Internacional de Comercialización de Sucedáneos de Leche Materna? Comité de Lactancia Materna de la Asociación Española de Pediatría. 2016. Available online: http://www.aeped.es/sites/default/files/documentos/201601-codigo-comercializacion-lm.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Crónica. Las leyes para proteger la lactancia materna son inadecuadas en la mayoría de los países. Rev. Chil. Obstet. Ginecol. 2016, 81, 265–266. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2016/breastfeeding/es/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Resolución de 13 de Noviembre de 2019, de la Secretaría General de Sanidad y Consumo, por la que se Publica el Convenio con la Iniciativa para la Humanización de la Asistencia al Nacimiento y la Lactancia, para la Promoción, Protección y Apoyo a la Lactancia Materna y Potenciación de la Humanización de la Asistencia al Nacimiento. BOE-A-2019–16775. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2019–16775 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Real Decreto 867/2008, de 23 de mayo, por el que se Aprueba la Reglamentación Técnico-Sanitaria Específica de los Preparados para Lactantes y de los Preparados de Continuación. BOE-A-2008–9289. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2008–9289 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Celebrating the Innocenti Declaration on the Protection, Promotion and Support of Breast-Feeding: Past Achievements, Present Challenges and Priority Actions for Infant and Young Child Feeding, 1990–2005. Available online: www.unicef-irc.org (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- COD—Ordinary Legislative Procedure (Ex-Codecision Procedure), 2017/0085(COD). Available online: https://oeil.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/popups/printficheglobal.pdf?id=681594&l=en (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Mutual Information System on Social Protection (MISSOC). Available online: https://www.missoc.org/missoc-database/comparative-tables/results/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service Authors: Ulla Jurviste, Martina Prpic, Giulio Sabbati Members’ Research Service PE 635.586. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2019/635586/EPRS_ATA(2019)635586_EN.pdf%20(europa.eu) (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Ley 3/1989, de 3 de Marzo, por la que se Amplía a Dieciséis Semanas el Permiso por Maternidad y se Establecen Medidas para Favorecer la Igualdad de Trato de la Mujer en el Trabajo. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-1989–5272 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- BOE-A-2019–3244. Real Decreto-ley 6/2019, de 1 de Marzo, de Medidas Urgentes para Garantía de la Igualdad de Trato y de Oportunidades Entre Mujeres y Hombres en el Empleo y la Ocupación. Available online: http://www.boe.es (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Agencia Estatal Boletin Oficial del Estado. BOE-A-2020–839. Resolución de 10 de enero de 2020, de la Dirección General de Trabajo, por la que se Registra y Publica el Convenio Colectivo de NCR España, SL. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2020–839 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Gómez Fernández-Vegue, M.; Menéndez Orenga, M. Encuesta Nacional Sobre Conocimientos de Lactancia Materna de los Residentes de Pediatría en España. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2019, 93, e201908060. [Google Scholar]

- Bagci Bosi, A.T.; Eriksen, K.G.; Sobko, T.; Wijnhoven, T.M.; Breda, J. Prácticas y políticas de lactancia materna en los Estados miembros de la Región de Europa de la OMS. Nutr. Salud Pública 2016, 19, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IHAN. Calidad en la Asistencia Profesional al Nacimiento y la Lactacia. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/pdf/equidad/IHAN.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Plan de Calidad para el Sistema Nacional de Salud. Salud y Género. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/organizacion/sns/planCalidadSNS/equidad/saludGenero/saludSexualReproduccion/IHAN.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Díaz-Gómez, N.M.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M.; Ares, S.; Espiga, I.; De Alba, C. Motivaciones y barreras percibidas por las mujeres españolas en relación a la lactancia materna. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2016, 90, 15.e1–15.e18. [Google Scholar]

- Rius, J.M.; Ortuno, J.; Rivas, C.; Maravall, M.; Calzado, M.A.; López, A.; Aguar, M.; Vento, M. Factores asociados al abandono precoz de la lactancia materna en una región del este de España. An. Pediatr. 2014, 80, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Martínez, E.; Gómez del Pulgar, M.; Pérez Martín, A.; Onieva Zafra, M.D.; Parra Fernández, M.L.; Beneit Montesinos, J.V. Análisis de la definición de la matrona, acceso a la formación y programa formativo de este profesional de la salud a nivel internacional, europeo y español. Educ. Médica 2018, 19, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente-Pulido, S.; Custodio, E.; López-Giménez, M.R.; Sanz-Barbero, B.; Otero-García, L. Barriers and Facilitators for Exclusive Breastfeeding in Women’s Biopsychosocial Spheres According to Primary Care Midwives in Tenerife (Canary Islands, Spain). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brounéaus, K. In depth Intervieweing: The process, skills and ethics of interviews in peace research. In Understanding Peace Researcch: Methods and Challenges; Höglundand, K., Óberg, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Muñoz, C. Estudio cualitativo sobre la experiencia vivida durante la lactancia materna en un grupo de madres adolescentes orientadas desde la consulta de la Matrona. Rev. Paraninfo Digit. 2014, 20. Available online: http://www.index-f.com/para/n20/033.php. (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Melgar de Corral, G.; Aguado, M.D.D.; Villar de la Fuente, M.C.; Gallego Moreno, M.F. Dar el Pecho: Estudio Cualitativo Sobre los Grupos de Promoción de la Lactancia Materna en la Provincia de Toledo. Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Colección ATENEA nº 24. Cuenca, 2021; pp. 1–171. Available online: http://doi.org/10.18239/atenea_2021.24.00 (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Cortés-Rúa, L.; Díaz-Grávalos, G.J. Early interruption of breastfeeding. A qualitative study. Enferm. Clin. (Engl. Ed.) 2019, 29, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. La Ecología del Desarrollo Humano; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAC. Instituto Canario de Estadística de 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020 y 2021. Available online: https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac/ (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística). 2019 y 2021. Available online: https://ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/t20/e245/p04/provi/l0/&file=0ccaa002.px (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Organización Territorial de Tenerife. Available online: https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/sanidad/scs/mapa (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Hernández, T.B.; García, L.O. Técnicas conversacionales para la recogida de datos en investigación cualitativa: La entrevista (I). NURE Investig. Rev. Científica Enfermería 2008, 33, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, T.B.; García, L.O. Técnicas cualitativas para la recogida de datos en investigación cualitativa: La entrevista (II). NURE Investig. Rev. Científica Enfermería 2008, 34, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Alameda Cuesta, A.; Antona Rodríguez, A.; Barquero González, A.; Hernández, T.B.; Cano Arana, A.; Feria Lorenzo, D.J. Investigación en Cuidados. Módulo Transversal. (Investigación Cualitativa). Fundación para el Desarrollo de la Enfermería 2017, 2, 21–79. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurs. Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICT Services and System Development and Division of Epidemiology and Global Health; Open Code 4.02; University of Umeå: Umeå, Sweden, 2013.

- Medina, F.I.M.; Fernández, G.C.T. Breastfeeding problems prevention in early breast feeding through effective technique. Enfermería Global Nº 31. Rev. Electrónica Trimest. Enfermería 2013, 12, 443–444. [Google Scholar]

- González, I.A.; Huespe Auchter, M.S.; Auchter, M.C. Lactancia materna exclusiva factores de éxito y/o fracaso. Rev. Posgrado VIa Cátedra Med. 2008, 177, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, C.P.; Artieta Pinedo, I.; Grandes, G.; Espinosa Cifuentes, M.; Inda, I.G.; Payo Gordon, J. Necesidades percibidas por las mujeres respecto a su maternidad. Estudio cualitativo para el rediseño de la educación maternal. Atención Primaria 2016, 48, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Su, L.; Chong, Y.; Chan, Y.; Chan, Y.; Fok, D.; Tun, K.; Ng, F.S.; Rauff, M. Antenatal education and postnatal support strategies for improving rates of exclusive breast feeding: Randomised controlled trial. Bmj 2007, 335, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Ballesteros, E.M.; Piñero Navero, S.; Alarcos Merino, G.; Arenas Orta, M.T.; Jiménez Iglesias, V. El fomento postnatal de la lactancia materna: Los grupos de apoyo. NURE Investig. Rev. Científica Enfermería 2010, 49, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Gubler, T.; Krähenmann, F.; Roos, M.; Zimmermann, R.; Ochsenbein-Kölble, N. Determinants of successful breastfeeding initiation in healthy term singletons: A Swiss university hospital observational study. J. Perinat. Med. 2013, 41, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumbiganon, P.; Martis, R.; Laopaiboon, M.; Festin, M.R.; Ho, J.J.; Hakimi, M. Antenatal breastfeeding education for increasing breastfeeding duration. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 12, CD006425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, L.M.B.; Monteiro, J.C.S.; Stefanello, J.; Gomes-Sponholz, F.A.; Oriá, M.O.B.; Nakano, M.A.S. Exclusive breastfeeding and maternal self-efficacy among women of intimate partner violence situations. Texto Contexto—Enferm 2016, 25, e2910015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupo de trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre la atención al parto normal. Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre la atención al parto normal. Plan de Calidad para el Sistema Nacional de Salud del Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social. In Agencia de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias del País Vasco (OSTEBA); Agencia de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias de Galicia: Galicia, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grupo de trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre lactancia materna. Guía de Práctica Clínica sobre Lactancia Materna; Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; Agencia de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias del País Vasco-OSTEBA, Comunidad Autónoma: Vasca, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Martínez, M.M.; González Carrión, P.; Quiñoz Gallardo, M.D.; Rivas Campos, A.; Expósito Ruiz, M.; Zurita Muñoz, A.J. Instituto de Investigación Biosanitaria Ibs Granada. Evaluación de buenas prácticas en lactancia materna en un hospital materno infantil. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2019, 93, e201911088. [Google Scholar]

- Otal-Lospaus, S.; Morera-Liánez, L.; Bernal-Montañes, M.J.; Tabueña-Acin, J. El contacto precoz y su importancia en la lactancia materna frente a la cesárea. Matronas Prof. 2012, 13, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dozier, A.M.; Howard, C.R.; Brownell, E.A.; Wissler, R.N.; Glantz, J.C.; Ternullo, S.R.; Thevenet-Morrison, K.N.; Childs, C.K.; Lawrence, R.A. Labor Epidural Anesthesia, Obstetric Factors and Breastfeeding Cessation. 2013. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22696104 (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Cortés-Rúa, L.; Díaz-Grávalos, G.J. Interrupción temprana de la lactancia materna. Un estudio cualitativo. Enfermería Clínica 2019, 29, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Internacional Confederation of Midwives. Definición de Matrona 2005. Available online: http://www.Internationalmidwives.org/pdf/ICM%20Definition%20of%20the%20Midwife%202005-SPA.pdf10. (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Johnston, K.; Aarts, C.; Darj, E. First-time parents’ experiences of home based postnatal care in Sweden. Ups J. Med. Sci. 2010, 115, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Santiago, G.; Martín Orúe, C.M.; López Beltran, A.; Moreno Ruiz, G.; Patricio Peña, D. La matrona. El arte de acompañar, nuevos tiempos de la maternidad. Grupo de Trabajo de la Comisión de Matronas del Colegio Oficial de Enfermeras i Enfermeros de Tarragona. AgInf 2017, 21, 167–168. [Google Scholar]

- Furnieles-Paterna, E.; Hoyuelos-Cámara, H.; Montiano-Ruiz, I.; Peñalver-Julve, N.; Fitera-Lamas, L. Estudio comparativo y aleatorizado de la visita puerperal en el domicilio de la madre y en el centro de salud. Matronas Prof. 2011, 12, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Abou-Dakn, M.; Fluhr, J.W.; Gensch, M.; Woeckel, A. Positive effect of HPA lanolin versus expressed breastmilk on painful and damaged nipples during lactation. 2011. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20720454 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Thomson, G.; Dykes, F.; Hurley, M.A.; Hoddinott, P. Incentives as connectors: Insights into a breastfeeding incentive intervention in a disadvantaged area of North-West England. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrero-Pachón, M.P.; Olombrada-Valverde, A.E.; Martínez de Alegría, M.I. Papel de la enfermería en el desarrollo de la lactancia materna en un recién nacido pretérmino. Enferm Clin. 2010, 20, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero Diaz, P.; Burgos Rodríguez, M.J.; Mejía Ramírez de Arellano, M. Results of a health education intervention in the continuity of breastfeeding. Enfermería Clínica 2015, 25, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Morcillo, A.J.; Harillo-Acevedo, D.; Armero-Barranco, D.; Leal-Costa, C.; Moral-García, J.E.; Ruzafa-Martínez, M. Barriers Perceived by Managers and Clinical Professionals Related to the Implementation of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Breastfeeding through the Best Practice Spotlight Organization Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol-Pons, A.; Aubanell-Serra, M.; Vidal, M.; Ojeda-Ciurana, I.; Martí-Lluch, R.; Ponjoan, A. Breast feeding basic competence in primary care: Development and validation of the CAPA questionnaire. Midwifery 2016, 42, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Martín-Iglesias, S.; del-Cura-González, I.; Sanz-Cuesta, T.; Arana-Cañedo_Argüelles, C.; Rumayor-Zarzuelo, M.; Álvarez-de la Riva, M.; Lloret-Sáez_Bravo, A.M.; Férnandez-Arroyo, R.M.; Aréjula-Torres, J.L.; Aguado-Arroyo, ó.; et al. Effectiveness of an implementation strategy for a breastfeeding guideline in Primary Care: Cluster randomised trial. BMC Fam. Pract. 2011, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oribe, M.; Lertxundia, A.; Basterrechea, M.; Begiristain, H.; Santa Marina, L.; Villar, M.; Dorronsoro, M.; Amiano, P.; Ibarluzea, J. Prevalencia y factores asociados con la duración de la lactancia materna exclusiva durante los 6 primeros meses en la cohorte INMA de Guipúzcoa. Gac. Sanit. 2015, 29, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanos, R. La salud en todas las políticas. Tiempo de crisis, ¿tiempo de oportunidades? Informe SESPAS 2010. Gac. Sanit. 2010, 24 (Suppl. 1), 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester Arnal, R.; Gómez Martínez, S.; Gil Juliá, B.; Ferrándiz-Sellés, M.D.; Collado-Boira, E.J. Burnout y factores estresantes en profesionales sanitarios de las unidades de cuidados intensivos. Rev. Psicopatología Psicol. Clínica 2016, 21, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Marco, M.I.; López Ibort, M.N.; Vicente Edo, M.J. Reflexiones en torno a la Relación Terpéutica: ¿Falta de tiempo? Index Enfermería 2004, 13, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Carmen Sara, J.C. Lineamientos y estrategias para mejorar la calidad de la atención en los servicios de salud. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Pública 2019, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seckler, E.; Regauer, V.; Rotter, T.; Bauer, P.; Müller, M. Barreras y facilitadores de la implementación de vías de atención multidisciplinar en la atención primaria: Una revisión sistemática. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido Alba, F.; García-Agua Soler, N.; Martín, R.A.; García Ruiz, A.J. Crisis, gasto público sanitario y política. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2019, 93, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Batalla Martinez, C.; Gené Badia, J.; Mascort Roca, J. ¿Y la Atención Primaria durante la pandemia? Atención Primaria 2020, 52, 598–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, V. The mistake of austerity policies, including cuts, in the national health system. Gac Sanit 2012, 26, 174–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Darias, A.; Diaz-Gomez, N.M.; Rodriguez-Martin, S.; Hernandez-Perez, C.; Aguirre-Jaime, A. ‘Supporting a first-time mother’: Assessment of success of a breastfeeding promotion programme. Midwifery 2020, 85, 102687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, E.; León, M. Políticas de igualdad de género y sociales en España. Investig. Fem. 2014, 5, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero Martínez, M.H. “Políticas de promoción de lactancia materna en España y Europa: Un análisis desde el género”. En Massó Guijarro, Ester: Mamar: Mythos y lógos sobre lactancia humana. ILEMATA. Rev. Int. Éticas Apl. 2017, 25, 201–215. [Google Scholar]

- Gitz, E. Lactancia: ¿una responsabilidad materna? Bordes. Rev. Política Derecho Sociedad 2020. Available online: http://revistabordes.com.ar (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Häggkvist, A.P.; Brantsæ, A.L.; Grjibovski, A.M.; Helsing, E.; Meltzer, H.M.; Haugen, M. Prevalence of breast-feeding in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study and health service-relate correlates of cessation of full breast-feeding. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 2076–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CCL Family Found. Good breastfeeding policies-good breastfeeding rates. CCL Fam. Found 1998, 24, 15. [Google Scholar]

- García Flores, E.P.; Herrera Maldonado, N.; Martínez Peñafiel, L.; Pesqueira Villegas, E. Violaciones al Código Internacional de Comercialización de Sucedáneos de Leche Materna en México. Acta Pediátrica México 2017, 38, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| North | South | Metropolitan | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of inhabitants | 224.047 | 291.706 | 388.960 | 904.713 |

| Number of foreign inhabitants | 14.218 | 81.875 | 21.103 | 117.196 |

| Employed population (in thousands) | 93.42 | 129.78 | 172.04 | 395.24 |

| Number of BHZ | 12 | 10 | 17 | 39 |

| Subcategories | Quotes from the Midwives |

|---|---|

| Contradictory messages by healthcare professionals who are poorly trained in EBF The informants point out the lack of training of healthcare professionals as an important negative factor for EBF. Conflicting and erroneous messages given to women can have dire consequences for EBF. | “…they do it with good will, but obviously when you are not up-to-date, then you talk about what you have gone through, what you remember was done ten years ago, and so you give wrong information which causes anxiety to the patient.” (E12) |

| Negative comments by health professionals about the ability of women to breastfeed Midwives indicate that negative comments, without scientific evidence, made by health professionals about the anatomy and functionality of the breast can lead to the cessation of EBF, since they foster uncertainty in women. | “Sometimes, it´s not so much about the wrong advice, but how I impose my advice. It´s best not to say anything than to say: ‘Oh, but you don’t have milk!’ ‘Oh, your breasts are soft, hasn´t your milk come in yet?’” (E3) |

| Health professionals insist on the maintenance of EBF without offering any solutions to the problems that arise The informants point out that Primary Care healthcare professionals insist on women continuing with EBF, despite the pain, without offering any solutions. The possible explanation for this could be the lack of training in BF. | “But if it’s hurting and you don’t give me any solution, I have a crack and you don’t know what to do with me, you just scold me to keep breastfeeding in pain, well, women just give up breastfeeding…” (E4) |

| Early introduction of other foods as a barrier to EBF Midwives regret the early introduction of formula and complementary feeding. The lack of scientific evidence of some recommendations given by some health professionals calls EBF into question. | “The early introduction of complementary feeding by paediatricians is a tremendous battleground, and in the health centres there are no common criteria regarding this.” (E5) |

| Non-compliance with the International Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes The informants claim it is necessary to monitor and penalise the cases where there is non-compliance in order to protect BF. | “… The agreement for commercialisation of breast milk substitutes is not complied with, it is almost always violated in all centres. The professionals themselves do not comply with it and there is no follow-up to see who complies and who does not, and there is no repercussion for those who do not comply…” (E2) |

| Subcategories | Quotes from the Midwives |

|---|---|

| Choice of the reference healthcare professional by women as a protective factor for EBF. Midwives highlight the importance of the woman having a reference healthcare professional for her EBF to be successful. They also point out that it is important for the entire Primary Care team who is in contact with the woman and her child to have adequate training and give the same information. | “…it is important for women to have a reference, at the professional level, who encourages breastfeeding, has knowledge about breastfeeding and knows how to solve difficulties…breastfeeding usually works…” (E1) |

| Support of EBF by healthcare professionals benefits EBF. Midwives consider the support of EBF by healthcare professionals essential to promote and maintain EBF. Women need to feel accompanied to solve the difficulties that may arise during EBF. | “The most important thing is that they do not feel alone, that they don´t feel abandoned, that someone is listening to them, that pain is given the necessary importance even if it has no physiological or anatomical explanation…” (E3) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llorente-Pulido, S.; Custodio, E.; López-Giménez, M.R.; Otero-García, L. Barriers and Facilitators for Exclusive Breastfeeding within the Health System and Public Policies from In-Depth Interviews to Primary Care Midwives in Tenerife (Canary Islands, Spain). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010128

Llorente-Pulido S, Custodio E, López-Giménez MR, Otero-García L. Barriers and Facilitators for Exclusive Breastfeeding within the Health System and Public Policies from In-Depth Interviews to Primary Care Midwives in Tenerife (Canary Islands, Spain). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010128

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlorente-Pulido, Seila, Estefanía Custodio, María Rosario López-Giménez, and Laura Otero-García. 2022. "Barriers and Facilitators for Exclusive Breastfeeding within the Health System and Public Policies from In-Depth Interviews to Primary Care Midwives in Tenerife (Canary Islands, Spain)" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010128

APA StyleLlorente-Pulido, S., Custodio, E., López-Giménez, M. R., & Otero-García, L. (2022). Barriers and Facilitators for Exclusive Breastfeeding within the Health System and Public Policies from In-Depth Interviews to Primary Care Midwives in Tenerife (Canary Islands, Spain). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010128