Abstract

Despite persistent disparities in maternity care outcomes, there are limited resources to guide clinical practice and clinician behavior to dismantle biased practices and beliefs, structural and institutional racism, and the policies that perpetuate racism. Focus groups and interviews were held in communities in the United States identified as having higher density of Black births. Focus group and interview themes and codes illuminated Black birthing individual’s experience with labor and delivery in the hospital setting. Using an iterative process to refine and incorporate qualitative themes, we created a framework in close collaboration with birth equity stakeholders. This is an actionable, cyclical framework for training on anti-racist maternity care. The Cycle to Respectful Care acknowledges the development and perpetuation of biased healthcare delivery, while providing a solution for dismantling healthcare providers’ socialization that results in biased and discriminatory care. The Cycle to Respectful Care is an actionable tool to liberate patients, by way of their healthcare providers, from biased practices and beliefs, structural and institutional racism, and the policies that perpetuate racism.

1. Introduction

Black birthing people and babies are consistently the most impacted by adverse health outcomes in the United States, and growing literature suggests that experiences of racism and disrespect during healthcare encounters impacts health [1]. Decades of medical and public health research have failed to explain or reduce race-associated differences in maternal outcomes—such as mortality, morbidity, and patient experiences—in the United States. Women of color (i.e., Black, Latina, and Asian women) are more likely to experience a comorbid illness [2] and maternal death [3] and report being unfairly treated within healthcare settings based on their race or ethnicity [4,5]. In addition to increasing trends in maternal mortality overall, perhaps more distressing is the persistent, large, and increasing mortality gaps between Non-Hispanic (NH) Black and all other birthing persons in the United States [3,6]. Healthcare provider factors- delayed response to clinical warning signs, followed by ineffective care- were the most common type of contributor to maternal deaths [5]. An actionable framework that centers Black birthing people, those most impacted by disrespectful treatment and care, is needed to resolve persistent maternal outcome disparities.

2. Shifts in Policy and Practice

In wealthy countries like the United States, there is a grassroot and political call to action for a radical shift in practice to reduce inequities in birth outcomes using respectful maternity care as a model for change [7]. The concept of Respectful Care, “care provided to all women in a manner that maintains their dignity, privacy and confidentiality, ensures freedom from harm and mistreatment, and enables informed choice and continuous support during labor and childbirth” [8] is globally accepted. The World Health Organization has called for further research on defining and measuring disrespect in public and private facilities, [5] yet there is not consensus of the ways to improve respectful care.

3. Taking Action to Address Maternal Outcome Disparities

This study was developed in response to the growing demand for frameworks to achieve birth equity and promote respectful maternity care in clinical settings that is informed by patients. Current data relies on system needs and does not adequately address the needs of birthing people. In order to address the needs of birthing people, it is necessary to illuminate birthing experiences to inform the ways in which systems might be improved to address disparities in maternal outcomes. The purpose of this study is to create an actionable framework for the practice of respectful maternity care based on the experiences of Black birthing people. This was achieved by eliciting feedback from Black birthing individuals across the United States and incorporating the findings to inform a framework to achieve respectful care. To achieve birth equity and a standard of respectful care, it is time to challenge the frameworks used and the values upheld to determine data collection and quality improvement activities. These measures currently detect symptoms of dysfunction, not the cause [9]. Focusing on easily measurable markers of quality diverts resources from harder-to-measure aspects of care, resulting in unchanged or even worse quality overall [9]. Recent studies support efforts to quantify and codify respectful care as well as address the need for radical change in medical practice [10].

4. Methods

In order to ensure the research process centers the experiences of Black birthing people, the research team identified three frameworks to guide the approach for participant recruitment, facilitation, development of the facilitator guide, analysis of the findings, and framework development. Cultural humility [11], Reproductive Justice [12], and Research Justice [13] are the guiding research frameworks of this study. Cultural Humility incorporates a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique to address power imbalances in the patient-physician interactions in order to develop a mutually beneficial and non-hierarchical clinical and advocacy partnership with communities on behalf of the individuals and populations [11]. Reproductive Justice is the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy in an individuals’ decision to have or not have children and to parent children in a safe and sustainable community [12]. Research Justice centers community voices and leadership to be active participants in the process for change and policy reform at local, regional, national, and global levels in order to facilitate lasting social change [13]. Together these frameworks: (a) address the hierarchical structure of medicine, that has historically set aside the needs of the patient, in order to center the needs and experiences of the patient; (b) center the experiences of Black birthing people and the communities they live in; and (c) promote actionable solutions.

5. Data Collection

This study was approved by the Institute of Women and Ethnic Studies (IWES) IRB.

Development of the facilitator guide was informed by an extensive review of literature; feedback from Birthing Justice and Birth Equity activists and researchers, health services researchers, the Institute for Women and Ethnic Studies, and health care providers (e.g., midwives, OB/Gyn physicians, doulas, lactation consultants, nurses, etc.); and Dr. Karen Scott’s Sacred Birth research [14]. All focus groups were co-facilitated by leaders of CBOs serving local communities of Black families.

All participants were given the option of a one-on-one interview to ensure their comfort in sharing their birthing experiences Before the focus group or interview, participants completed a questionnaire that included demographic information, information about utilization of healthcare services, and access to healthcare services. Guiding questions were developed based on a review of the literature and the expertise of study investigators from various disciplines (birth equity research, reproductive justice, health services research, OB/Gyns, and sociology) and tested in a pilot focus group. Modifications were made in the interview guide to decrease the number of questions.

To illuminate the birthing experiences of Black birthing individuals in hospital labor and delivery units, we conducted qualitative focus group discussions and an interview to identify the components of respectful maternity care. All focus groups were moderated and led by two leaders of community-based organizations serving Black birthing communities trained by the research team on facilitation of focus groups and the study research methods. A member of the research team (CLG) was available to the moderators for support and co-facilitation during the focus groups. Focus groups and interviews lasted 2-h.

Childcare was provided and participants were compensated $150 for their time and other study related expenses (e.g., transportation, childcare) related to participation.

6. Data Analysis

Digital recordings were transcribed verbatim and reviewed for accuracy in transcription. A team of five (5) scholars with backgrounds and expertise in maternal mental health, Black birthing justice, health services research, and birth equity independently reviewed the transcripts. The team identified overarching themes that were then further refined using codes. Codes were applied to each of the transcripts in a line-by-line coding process. Coders paid specific attention to the role of racism and discrimination in the treatment and care of participants. Themes and codes were developed and identified in relationship to participants’ experiences as Black birthing people. The expansiveness, range of ethnic and cultural groups, of the African diaspora has influenced family lineage in many different countries, and researchers did not want to discount the experience of any birthing person who may inform this inquiry on respectful maternity care.

Data were independently reviewed by three coders. Coders discussed the themes and codes and came to a consensus on recurrent themes, conceptual descriptions, and illustrative examples of respectful care and compiled a codebook for assessing the remaining transcripts. To be included as a salient aspect of respectful care, a theme has to appear in two or more focus groups. Community based organization (CBO) leaders and partners that provide services for black birthing individuals and communities reviewed the preliminary codes and the remaining transcripts were then reviewed.

CBO leaders collaborated with the research team for the initial identification of themes and codes and remained engaged during data analysis. CBO leaders were asked to critically evaluate the codes and draft models in our community validation process. As themes and codes were refined, the research team checked-in with the CBO leaders to ensure the themes and codes were representative of the experiences of their communities and that key themes and concepts were not overlooked. After completion of coding of all the transcripts, the CBOs reviewed the final codes and unique definitions for each of the codes. Five of six CBO leaders refined themes based on the codes and their experiences, refined our definitions, and suggested de novo codes.

7. Creating the Framework

Once the themes and codes were established, CBO leaders were asked to provide feedback by walking through several exercises with the research team. The qualitative findings that were identified by the research team, CBO leaders, and stakeholders as critical to respectful care that were then examined in the context of existing frameworks in public health and health psychology. In the style of a listening session, CBO leaders were asked to apply the codes and themes to existing frameworks/models to contextualize the relationships of the codes and themes into the components of a framework to promote respectful maternity care.

8. Participant Recruitment

Data were collected in select communities of the United States identified as having higher density of Black births—Atlanta, GA; Baltimore, MD; Chicago, IL; Dallas, TX; Houston, TX; and Tulsa, OK during the Spring and Summer of 2019. Participants were recruited by community-based organizations located in these cities that provide resources and support for Black Birthing individuals in these communities.

The researchers and CBO partners recruited Black birthing people, over 18 years old, who had a birthing experience in a local hospital facility within the last two years. Blackness and identifying as Black includes a wide range of ethnic diversity, including African immigrants, Indigenous groups, Afro-Latinx, mixed race, etc. It was important that participants self-identified as Black and Blackness is a personal identity. In the participant demographic questionnaire, they were all asked to identify their race and gender identity. As all participants identified as Black and as women, they will be referred to as Black mothers for the duration of the report.

9. Framework Development

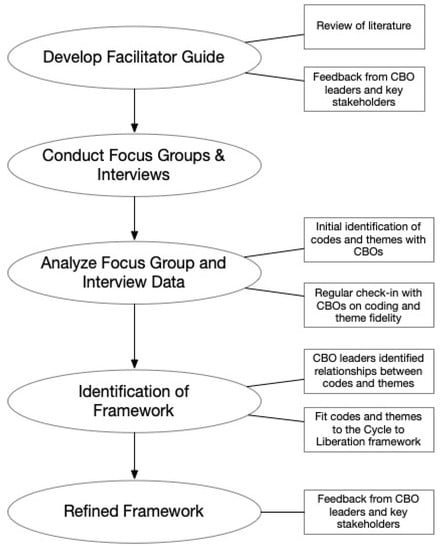

The themes and codes were applied to develop a framework for achieving respectful maternity care with the feedback and input from stakeholders (e.g., clinicians, nurses, birth workers, professional organizations, and health service researchers) and leadership from community-based organizations. After the identification of codes and themes, the research team and CBO leaders underwent an iterative process to develop a framework that were actionable steps for providers to practice respectful maternity care that included the themes from the focus groups. See Figure 1: Methods Process for an overview of this methodological approach.

Figure 1.

Methods Process. CBO: Community based organization.

10. Results

Seven focus groups with 3–11 participants per focus group and one (1) one-on-one interview (N = 50) were held with Black mothers. Participants represented numerous communities across the United States and a range of socioeconomic backgrounds. See Table 1: Participant Demographics and Characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Characteristics.

The research team explored and presented numerous existing models and frameworks including the Bronfenbrenner Ecological Model [15], the Feminist Ecological Model [16], and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs [17] to stakeholders and CBO leaders in order to provide context for how the themes and codes might fit into existing frameworks and models.

CBO leaders unanimously rejected the idea of a hierarchical framework to achieve respectful care, noting that the absence of respect does not prevent a birth from happening, such that there is no one value or event that leads to a respectful birth experience. CBO leaders identified a need for a model of respectful care that was cyclical and relational, rather than hierarchical. The CBO leaders asserted that a linear process is irrelevant in communicating how providers achieve respectful care and that respectful care is dependent on antiracism and eliminating individual racist beliefs. They unanimously accepted the depiction of the cyclical model that promotes ongoing growth toward respectful care practices by confronting racism.

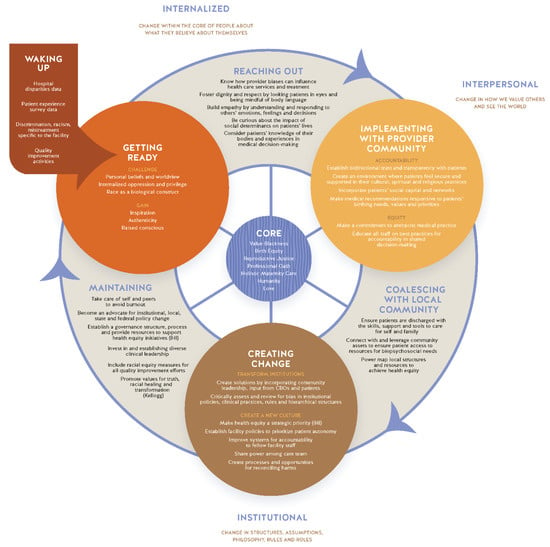

A CBO leader introduced the research team to Bobby Harro’s Cycles of Liberation [18] and Socialization [19]. Examining all the existing frameworks and models, all research partners arrived at a consensus that a cyclical model best illustrates the continuous and ongoing work of achieving respectful care. The Cycle of Liberation was adapted to include focus group themes to arrive at the Cycle to Respectful Care.

Themes and codes identified from the focus groups were incorporated into the Cycle to Liberation. (See Figure 2: Cycle to. Respectful Care) To fit the Cycle to Liberation with the focus groups and interview findings, the research team used an iterative process engaging CBO leadership, Birthing Justice and Birth Equity activists and researchers, health services researchers, birth equity researchers, leaders at professional organizations, and health care providers (e.g., midwives, OB/Gyn physicians, doulas, lactation consultants, nurses, etc.) to integrate the themes and codes into, what is now, the Cycle to Respectful Care. In addition to the feedback from key stakeholders, the research team identified existing quality improvement initiatives and models of care to incorporate into the framework to provide actionable solutions. The iterative process led to the Cycle to Respectful Care.

Figure 2.

Cycle to Respectful Care.

11. The Core of the Cycle to Respectful Care

The core connects to each section of the cycle. Therefore, as a person progresses around the cycle the core values remain. Some of the values are present when a person first enters the cycle, those values are then fostered, expanded upon, and matured as they proceed through the various phases. The core values of the Cycle of Respectful Care include valuing patients’ Black Intersectionality [1,5], Birth Equity, Reproductive Justice [12,20], the Professional Pledge/Oath [5] healthcare professionals commit to at the start of their career, Holistic Maternity Care, Humanity [21,22,23], and Love of self and others. (See Table 2: Definitions and Descriptions of the Core.) Values are strengthened through each phase, as they exist and operate on both the individual and collective levels. Harm can come from anywhere, but for the purpose of illustrating the ways in which the cycle could be put into practice Table 3: Examples of Individuals Moving through the Cycle illustrates the process by which a physician, nurse, and patient might move through the cycle. See Table 4: Moving through the Cycle to Respectful Care for the rationale and evidence for each phase.

Table 2.

Definitions and Descriptions of the Core.

Table 3.

Examples of Individuals Moving through the Cycle.

Table 4.

Moving through the Cycle to Respectful Care.

12. Discussion

Historically, research in underserved communities has not included community partners, instead it has made these communities serve as laboratories, and the community members as experimental subjects [37]. This study engaged birthing communities, stakeholders, and organizations, which allowed for unique insight about specific needs and health impacts observed by Black mothers. Participants’ social and cultural experiences informed our study methods, research questions, research findings, and the iterations in the development of the Cycle for Respectful Care. Active and informed participation of birthing people in all aspects of the design and implementation of institutional change was critical for constructive accountability [1,38].

Qualitative findings illuminated the hospital birthing experiences of Black birthing people to inform an actionable framework for healthcare providers and birth workers to address persistent and widening disparities in maternal health outcomes. Engagement with stakeholders at all steps of the research process ensured fidelity to centering the experiences of Black birthing people. An iterative process to identifying a framework that appropriately contextualizes the themes and codes of the qualitative findings resulted in the Cycle to Respectful Care—an actionable framework to address biased and disrespectful care. A high level of trust was established and investment in the process was mutual.

Accordingly, the Cycle to Respectful Care framework combines theory, analysis, and experiences of Black mothers across the United States It describes a recurrent process that is reminiscent of successful social change efforts, which led to some extent of liberation from the negative impact of oppressive systems for everyone involved. The Cycle to Respectful Care supports intentional patient engagement, promotes advocacy, and is an actionable tool to address birth equity in maternity care. The Cycle to Respectful Care framework was created for health systems and providers as an actionable guide toward respectful care for Black mothers, and eventually all birthing people.

The Cycle to Respectful Care is a tool for health care providers to understand how their Black patients experience disrespect, and how patients could be liberated from biased practices and beliefs, structural and institutional racism, and the policies that perpetuate racism. The primary provider audience for this framework is physicians, nurse midwives, and nurses because participants’ hospital and clinic experiences are highly influenced by these individuals. Any care provider can operate in a disrespectful practice that may or may not be rooted in racism. Though this framework is written for the direct use of medical professionals, it can be used by any health care professional who serves Black birthing people in their reproductive life course.

The Cycle to Respectful Care flows through the levels of racism [39], internalized racism, personally mediated racism, and institutionalized racism [40]. Harro [18] claims that a person can start anywhere on the Cycle of Liberation, but that it is usually inevitable that intrapersonal, interpersonal, and systemic change will transpire while using this framework, which causes one to “wake up”. After entering, one may repeat the process many times as there is no end to pursuing equity.

The Cycle to Respectful Care theoretical framework is based on the birth experiences of Black mothers in order to inform the ways in which to achieve respectful care. This framework complements existing provider educational tools, promotes anti-racist and birth equity practices, and bridges community assets to hospital care by centering the cultural, biopsychosocial, and holistic needs of Black mothers in order to reduce disparities in clinical and patient reported experience measure outcomes for all birthing people.

Limitations of this study were that one of the six CBO leaders was not able to participate in the development of the framework and validation of the qualitative analysis. Other limitations were that the communities selected for recruitment were based on a convenience sample of the areas where the research team had established relationships. This resulted in a lack of geographic spread that excluded middle America and rural communities.

As hospitals and health systems look for solutions to promoting equity and resolving disparities, this framework is a guide for hospital staff and administrators who seek to achieve equity in their practice. The development of the Cycle to Respectful Care framework will ensure that hospital staff have tools to introduce and continuously work toward respectful care practices. As tools to address the patient led development and validation of measures for respect and discrimination in maternity care progress, a clinical standard for community engages quality improvement will emerge. From the perspective of professional responsibility and anti-racism, it should be expected that healthcare providers prioritize frameworks created for, by and with Black birthing people.

13. Conclusions

The Cycle to Respectful Care theoretical framework underscores the process to achieving respectful care for Black mothers and all birthing people. This framework is the inception of Respectful Maternity Care provider education tools, community awareness messaging, and a patient reported experience measure. The framework is expected to have applications in healthcare quality improvement initiatives for improving experiences and outcomes for birthing people (Supplementrary Material see PREM FACILITATOR GUIDE).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph18094933/s1.

Author Contributions

C.L.G. and J.A.C.-P. conceived of the original project idea. C.L.G. conducted the study with support from A.W., C.L.G., S.L.P., A.W. and T.E. wrote the manuscript with support from S.M.O., T.C.A. and J.A.C.-P., S.M.O., T.C.A. and J.A.C.-P. supervise the project. S.L.P., A.W. and T.E. encouraged C.L.G. to investigate incorporating qualitative findings into a framework. S.M.O. and T.C.A. supervised the findings of this work. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant number 76153.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Institute for Women and Ethnic Studies (protocol code PREM and 8 September 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to data that may potentially compromise participant anonymity.

Acknowledgments

The research conducted by the National Birth Equity Collaborative research team was made possible by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, with administrative support of our fiscal sponsor, Foundation for Louisiana. Thanks to Karen Scott’s visionary leadership with the Sacred Birth Initiative, funded the California Health Care Foundation. Our deepest gratitude to the Chief Executive Officer of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist, Maureen Phipps, and our CBO partners and community leaders; Maurianna Adams, Angela Doyinsola-Aina, Tamela Milan Alexander, Tanay Lynn Harris, Marsha Jones, Kay Matthews, Nia Mitchell, and Reverend Deneen Robinson.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McLemore, M.R.; Altman, M.R.; Cooper, N.; Williams, S.; Rand, L.; Franck, L. Health care experiences of pregnant, birthing and postnatal women of color at risk for preterm birth. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 201, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridman, M.; Korst, L.M.; Chow, J.; Lawton, E.; Mitchell, C.; Gregory, K.D. Trends in maternal morbidity before and during pregnancy in California. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, S49–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, E.E.; Davis, N.L.; Goodman, D.; Cox, S.; Syverson, C.; Seed, K.; Shapiro-Mendoza, C.; Callaghan, W.M.; Barfield, W. Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths—United States, 2007–2016. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakala, C.; Declercq, E.; Turon, J.; Corry, M. Listening to Mothers in California: A Population-Based Survey of Women’s Childbearing Experiences; National Partnership for Women & Families: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vedam, S.; Stoll, K.; Taiwo, T.K.; Rubashkin, N.; Cheyney, M.; Strauss, N.; McLemore, M.; Cadena, M.; Nethery, E.; Rushton, E. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: Inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.E.; Davis, N.L.; Goodman, D.; Cox, S.; Mayes, N.; Johnston, E.; Syverson, C.; Seed, K.; Shapiro-Mendoza, C.K.; Callaghan, W.M. Vital signs: Pregnancy-related deaths, United States, 2011–2015, and strategies for prevention, 13 states, 2013–2017. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amutah-Onukagha, N.; Howell, E.; Crear-Perry, J.A.; Underwood, L. A Path to Reproductive Justice: Research, Practice and Policies. In Advancing Racial Equity; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, J.M. Professionalism Revealed: Rethinking Quality Improvement in the Wake of a Pandemic. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crear-Perry, J.; Maybank, A.; Keeys, M.; Mitchell, N.; Godbolt, D. Moving towards anti-racist praxis in medicine. Lancet 2020, 396, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervalon, M.; Murray-Garcia, J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 1998, 9, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reproductive Justice. Available online: https://www.sistersong.net/reproductive-justice/ (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Jolivétte, A. Research Justice: Methodologies for Social Change; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, K.A.; Britton, L.; McLemore, M.R. The ethics of perinatal care for black women: Dismantling the structural racism in “mother blame” narratives. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2019, 33, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Systems Theory; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Balogun-Mwangi, O.; Matsumoto, A.; Ballou, M.; Faver, L.; Todorova, I. Women’s Pain, Women’s Voices: Using the Feminist Ecological Model and a Participatory Action Research Approach in Developing a Group Curriculum for Chronic Pain. J. Ethnogr. Qual. Res. 2016, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.; Lewis, K. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs; Salenger Incorporated: Glenarm, IL, USA, 1987; Volume 14, p. 987. [Google Scholar]

- Harro, B. The cycle of liberation. Read. Divers. Soc. Justice 2000, 2, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bobbie, H.; Maurianne, A. The cycle of socialization. In Reading for Diversity and Social Justice; Adams, M., Blumenfeld, W.J., Castaneda, R., Hackman, H.W., Peters, M.L., Zuniga, X., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, L.; Solinger, R. Reproductive Justice: An Introduction; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Muse, S.; Gay, E.D.; Aina, A.D.; Green, C.; Crear-Perry, J.; Roach, J.; Tesfa, H.; Matthews, K.; Harris, T.L. Black Paper: Setting the Standard for Holistic Care of and for Black Women; Black Mamas Matter Alliance: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb, B.N.; Taylor, J.K.; Gay, E.D.; Aina, A.D.; Crear-Perry, J.; Roach, J.; Porcchia-Albert, C.; Nedhari, A.; Scott, C.; Williams, A.N.; et al. Advancing Holistic Maternal Care for Black Women through Policy; Black Mamas Matter Alliance: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. Universal Declaration of Human Rights; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 1948; Volume 302. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, L.A.; Elliott, M.N.; Goldstein, E.; Lehrman, W.G.; Spencer, P.A. Development, implementation, and public reporting of the HCAHPS survey. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2010, 67, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J. The alliance for innovation in maternal health care: A way forward. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 61, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendi, I.X. How to Be an Antiracist; One world: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- A Roadmap for Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities: The Four I’s for Health Equity; National Quality Forum: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 1–119.

- Wyatt, R.; Laderman, M.; Botwinick, L.; Mate, K.; Whittington, J. Achieving Health Equity: A Guide for Health Care Organizations; IHI White Paper; Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reduction of Peripartum Racial/Ethnic Disparities (+AIM). Available online: https://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/patient-safety-bundles/reduction-of-peripartum-racialethnic-disparities/#link_acc-1-5-d (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Crear-Perry, J.; Correa-de-Araujo, R.; Lewis Johnson, T.; McLemore, M.R.; Neilson, E.; Wallace, M. Social and structural determinants of health inequities in maternal health. J. Women’s Health 2020, 30, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, E.A.; Brown, H.; Brumley, J.; Bryant, A.S.; Caughey, A.B.; Cornell, A.M.; Grant, J.H.; Gregory, K.D.; Gullo, S.M.; Kozhimannil, K.B. Reduction of peripartum racial and ethnic disparities: A conceptual framework and maternal safety consensus bundle. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2018, 47, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, A.D.; Asiodu, I.V.; Castillo, P.; Denson, J.; Drayton, C.; Aka-James, R.; Mahdi, I.K.; Mitchell, N.; Morgan, I.; Robinson, A. Black Maternal Health Research Re-Envisioned: Best Practices for the Conduct of Research with, for, and by Black Mamas. Harv. Law Policy Rev. 2019, 14, 393. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, D.; Jegede, B.; Weir, S.; Canady, R. Practices to Reduce Infant Mortality through Equity: Recommendations for State Public Health Departments; Michigan Department of Community Health: Lansing, MI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, V.; Rowley, D.L.; White, S.B.; Faustin, Y. Dimensionality and R4P: A health equity framework for research planning and evaluation in African American populations. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.; Crear-Perry, J.; Richardson, L.; Tarver, M.; Theall, K. Separate and unequal: Structural racism and infant mortality in the US. Health Place 2017, 45, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, B.D.; Arabia, S.E.; Arega, H.A.; Altman, M.R.; Berkowitz, R.; Feuer, S.K.; Franck, L.S.; Gomez, A.M.; Kober, K.; Pacheco-Werner, T. Exposures to structural racism and racial discrimination among pregnant and early post-partum Black women living in Oakland, California. Stress Health 2020, 36, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, K. Community-Based Participatory Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, P.; Backman, G. Health systems and the right to the highest attainable standard of health. Health Hum. Rights 2008, 10, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.P. Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am. J. Public Health 2000, 90, 1212. [Google Scholar]

- Nuru-Jeter, A.; Dominguez, T.P.; Hammond, W.P.; Leu, J.; Skaff, M.; Egerter, S.; Jones, C.P.; Braveman, P. “It’s the skin you’re in”: African-American women talk about their experiences of racism. An exploratory study to develop measures of racism for birth outcome studies. Matern. Child Health J. 2009, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).