Refugee Women with a History of Trauma: Gender Vulnerability in Relation to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Refugees

1.2. Gender Differences and PTSD: Traumatic Experiences in Refugee Women

2. Method

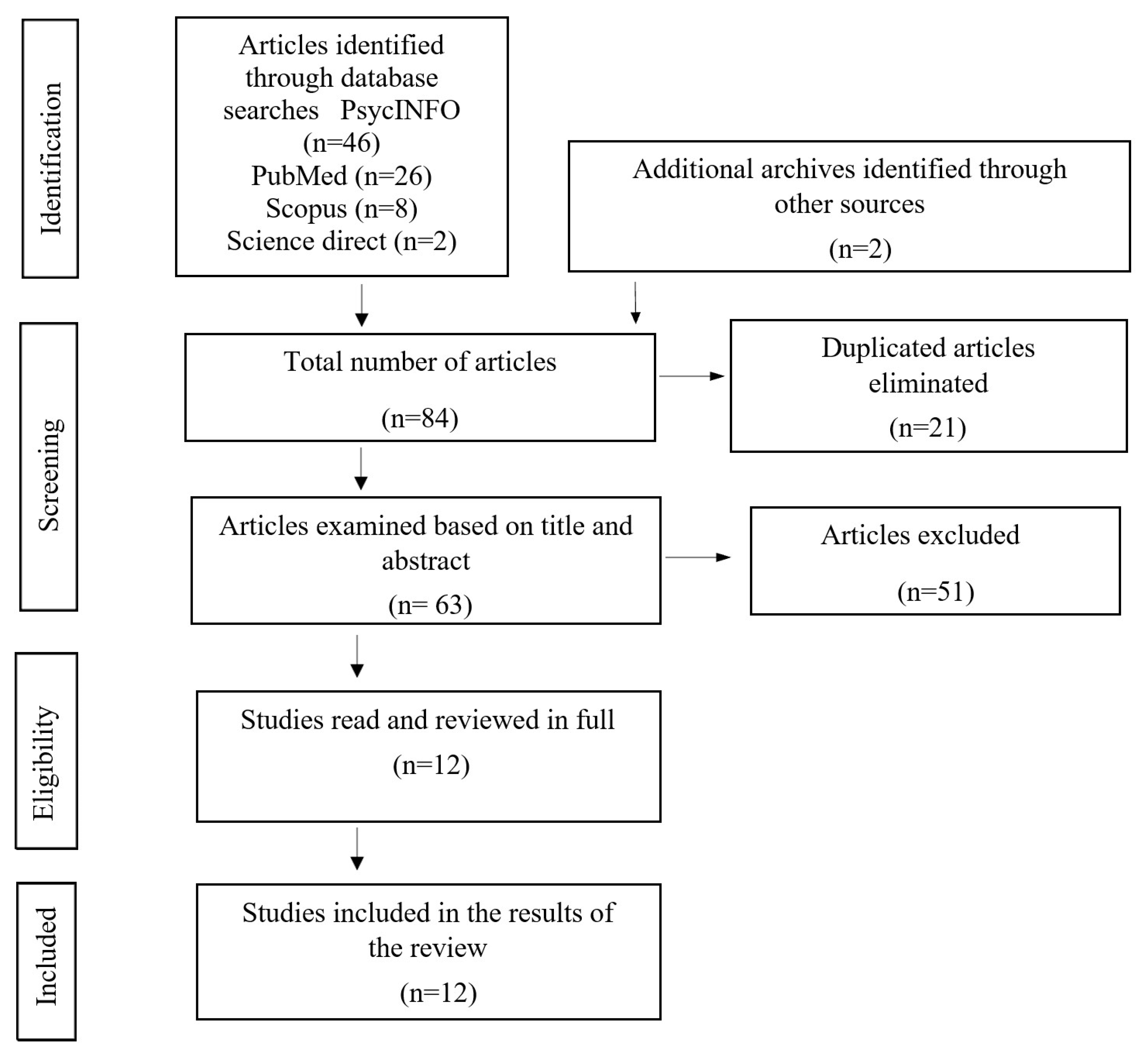

Literature Search and Study Selection

3. Results

3.1. PTSD and Other Mental Health Problems in Refugee Women

3.2. Differences in PTSD between Male and Female Refugees

3.3. Traumatic Experiences in Refugee Women: The Importance of Rape and Sexual Abuse

3.4. PTSD over Time

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research Lines

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Refugee Population Statistics; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/ (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Ellis, B.H.; Murray, K.; Barrett, C. Understanding the mental health of refugees: Trauma, stress, and the cultural context. In Current Clinical Psychiatry. The Massachusetts General Hospital Textbook on Diversity and Cultural Sensitivity in Mental Health; Parekh, R., Ed.; Human Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Führer, A.; Eichner, F.; Stang, A. Morbidity of asylum seekers in a medium-sized German city. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 31, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, A.V. Distinguishing distress from disorders psychological outcomes of stressful social arrangements. Health Interdiscip. J. Soc. Study Health Illn. Med. 2007, 11, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, S.M.; Huey, S.J., Jr.; Miranda, J. A critical review of current evidence on multiple types of discrimination and mental health. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2020, 90, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, T.; Liedl, A.; Ehring, T. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic factor in Afghan refugees. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angora, R.A. Trauma y estrés en población refugiada en tránsito hacia Europa. Clín. Contemp. 2016, 7, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleijpen, M.; June ter Heide, F.J.; Mooren, T.; Boeije, H.R.; Kleber, R.J. Bouncing forward of young refugees: A perspective on resilience research directions. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2013, 4, 20124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindert, J.; von Ehrenstein, O.S.; Priebe, S.; Mielck, A.; Brähler, E. Depression and anxiety in labor migrants and refugees–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesterko, Y.; Jäckle, D.; Friedrich, M.; Holzapfel, L.; Glaesmer, H. Health care needs among recently arrived refugees in Germany: A cross-sectional, epidemiological study. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reavell, J.; Fazil, Q. The epidemiology of PTSD and depression in refugee minors who have resettled in developed countries. J. Ment. Health 2017, 26, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorst-Unsworth, C.; Goldenberg, E. Psychological sequelae of torture and organised violence suffered by refugees from Iraq: Trauma-related factors compared with social factors in exile. Br. J. Psychiatry 1998, 172, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewin, C.R.; Dalgleish, T.; Joseph, S. A dual representation theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Rev. 1996, 103, 670–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Kolk, B.A. The body keeps the score: Memory and the evolving psychobiology of posttraumatic stress. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 1994, 1, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B.A.; Van der Hart, O. The intrusive past: The flexibility of memory and the engraving of trauma. Am. Imago 1991, 48, 425–454. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk, B.A. Psychobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. In Textbook of Biological Psychiatry; Panksepp, J., Ed.; Wiley-Liss: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 319–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B.A. Developmental Trauma Disorder: Toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatr. Ann. 2005, 35, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankink, M.; Richters, A. Silence as a coping strategy: The case of refugee women in the Netherlands from South-Sudan who experienced sexual violence in the context of war. In Voices of Trauma; Drožđek, B., Wilson, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; First, M.B.; Wakefield, J.C. Saving PTSD from itself in DSM-V. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007, 21, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muldoon, O.T.; Haslam, S.A.; Haslam, C.; Cruwys, T.; Kearns, M.; Jetten, J. The social psychology of responses to trauma: Social identity pathway associate with divergent traumatic responses. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 30, 311–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5); American Psychiatric Pub: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.; Khabbaz, F.; Legate, N. Enhancing need satisfaction to reduce psychological distress in Syrian refugees. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 84, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doctors Without Borders. Asylum Seekers in Italy: An Analysis of Mental HEALTH distress and Access to Healthcare. Available online: https://www.msf.org/italy-mental-health-disorders-asylum-seekers-and-migrants-overlooked-inadequate-reception-system (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- Crumlish, N.; O’Rourke, K. A systematic review of treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder among refugees and asylum-seekers. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010, 198, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priebe, S.; Giacco, D.; El-Nagib, R. Public health aspects of mental health among migrants and refugees: A review of the evidence on mental health care for refugees, asylum seekers and irregular migrants in the WHO European Region. In Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK391045/ (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Steel, Z.; Chey, T.; Silove, D.; Marnane, C.; Bryant, R.A.; Van Ommeren, M. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med Assoc. 2009, 302, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, A.C.; Atchison, M.; Rafalowicz, E.; Papay, P. Physical symptoms in post-traumatic stress disorder. J. Psychosom. Res. 1994, 38, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolin, D.F.; Foa, E.B. Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 959–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, M.G.; Resick, P.A.; Mechanic, M.B. Objective assessment of peritraumatic dissociation: Psychophysiological indicators. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, F.H. Epidemiology of trauma: Frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1992, 60, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Sonnega, A.; Bromet, E.; Hughes, M.; Nelson, C.B. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1995, 52, 1048–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Murphy, A.D.; Baker, C.K.; Perilla, J.L.; Rodríguez, F.G.; Rodríguez, J.D.J.G. Epidemiology of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in Mexico. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003, 112, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, J.; Kimerling, R. Gender issues in the assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder. In Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD; Wilson, J.P., Keane, T.M., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 192–238. [Google Scholar]

- Pimlott-Kubiak, S.; Cortina, L.M. Gender, victimization, and outcomes: Reconceptualizing risk. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortina, L.M.; Kubiak, S.P. Gender and posttraumatic stress: Sexual violence as an explanation for women’s increased risk. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2006, 115, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Chin Women from Myanmar Find Help Down a Winding Lane in Delhi; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: http://www.unhcr.org/4a76f7466.html (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Ward, J.; Vann, B. Gender-based violence in refugee settings. Lancet 2002, 360, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado (CEAR). Informe 2020: Las Personas Refugiadas en España y Europa. Available online: https://www.cear.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Informe-Anual_CEAR_2020_.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Quercetti, F.; Ventosa, N. Crisis de refugiados: Un análisis de las concepciones presentes en los estudios sobre la salud mental de las personas refugiadas y solicitantes de asilo. In VIII Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología XXIII. Jornadas de Investigación XII Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del MERCOSUR; Acta Académica: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2016; Available online: https://www.aacademica.org/000-044/280 (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Buckley-Zistel, S.; Krause, U. Gender, Violence, Refugees; Berghahn Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, E. Long-term effects of organized violence on young Middle Eastern refugees’ mental health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 1596–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rometsch-Ogioun El Sount, C.; Denkinger, J.K.; Windthorst, P.; Nikendei, C.; Kindermann, D.; Renner, V.; Ringwald, J.; Brucker, S.; Tran, V.M.; Zipfel, S.; et al. Psychological Burden in Female, Iraqi Refugees Who Suffered Extreme Violence by the “Islamic State”: The Perspective of Care Providers. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnett, A. Asylum seekers and refugees in Britain: Health needs of asylum seekers and refugees. BMJ 2001, 322, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokore, N. Suffering in silence: A Canadian-Somali case study. J. Soc. Work Pract. 2013, 27, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.J.; Arnett, J.J.; Jena, S.P.K. Experiences of Burmese Chin refugee women: Trauma and survival from pre-to postflight. Int. Perspect. Psychol. Res. Pract. Consult. 2017, 6, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 350, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.V.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Rothstein, H.R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, C.L.; Halcon, L.; Savik, K.; Johnson, D.; Spring, M.; Butcher, J.; Westermeyer, J.; Jaranson, J. Somali and Oromo refugee women: Trauma and associated factors. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redwood-Campbell, L.; Thind, H.; Howard, M.; Koteles, J.; Fowler, N.; Kaczorowski, J. Understanding the health of refugee women in host countries: Lessons from the Kosovar re-settlement in Canada. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2008, 23, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojvoda, D.; Weine, S.M.; McGlashan, T.; Becker, D.F.; Southwick, S.M. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in Bosnian refugees 3 1/2 years after resettlement. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2008, 45, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.; Scott, J.; Rughita, B.; Kisielewski, M.; Asher, J.; Ong, R.; Lawry, L. Association of sexual violence and human rights violations with physical and mental health in territories of the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2010, 304, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalinski, I.; Elbert, T.; Schauer, M. Female dissociative responding to extreme sexual violence in a chronic crisis setting: The case of Eastern Congo. J. Trauma. Stress 2011, 24, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ssenyonga, J.; Owens, V.; Olema, D.K. Traumatic experiences and PTSD among adolescent Congolese Refugees in Uganda: A preliminary study. J. Psychol. Afr. 2012, 22, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morof, D.F.; Sami, S.; Mangeni, M.; Blanton, C.; Cardozo, B.L.; Tomczyk, B. A cross-sectional survey on gender-based violence and mental health among female urban refugees and asylum seekers in Kampala, Uganda. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 127, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalinski, I.; Moran, J.; Schauer, M.; Elbert, T. Rapid emotional processing in relation to trauma-related symptoms as revealed by magnetic source imaging. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alpak, G.; Unal, A.; Bulbul, F.; Sagaltici, E.; Bez, Y.; Altindag, A.; Dalkilic, A.; Savas, H.A. Post-traumatic stress disorder among Syrian refugees in Turkey: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2014, 19, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldane, J.; Nickerson, A. The impact of interpersonal and noninterpersonal trauma on psychological symptoms in refugees: The moderating role of gender and trauma type. J. Trauma. Stress 2016, 29, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhlongo, M.D.; Tomita, A.; Thela, L.; Maharaj, V.; Burns, J.K. Sexual trauma and post-traumatic stress among African female refugees and migrants in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Psychiatry 2018, 24, 1208. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence Against Women: Initial Results on Prevalence, Health Outcomes and Women’s Responses. 2005. Available online: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/24159358X/en/ (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Robbers, G.M.L.; Morgan, A. Potencial de programas para la prevención y respuesta a la violencia sexual contra mujeres refugiadas: Una revisión de la literatura. Reprod. Health Matters 2018, 25, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, A.; Adam, A.; Wirtz, A.; Pham, K.; Rubenstein, L.; Glass, N.; Beyrer, C.; Singh, S. The Prevalence of Sexual Violence among Female Refugees in Complex Humanitarian Emergencies: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. PLoS Curr. 2014, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Against Refugees, Returnees, and Internally Displaced Persons; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/protection/women/3f696bcc4/sexual-gender-based-violence-against-refugees-returnees-internally-displaced.html (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Working with Men and Boy Survivors of Sexual and Gender-BASED Violence in Forced Displacement; UNHCR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Available online: https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5006aa262.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Gupta, M.A. Review of somatic symptoms in post-traumatic stress disorder. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2013, 25, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, C.W.; Terhakopian, A.; Castro, C.A.; Messer, S.C.; Engel, C.C. Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with somatic symptoms, health care visits, and absenteeism among Iraq war veterans. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribor, E.F.; Yutzy, S.H.; Dean, J.T.; Wetzel, R.D. Briquet’s syndrome, dissociation, and abuse. Am. J. Psychiatry 1993, 150, 1507–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Scaer, R.C. The Body Bears the Burden: Trauma, Dissociation and Disease; The Haworth Medical Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Spangaro, J.; Adogu, C.; Zwi, A.B.; Ranmuthugala, G.; Davies, G.P. Mechanisms underpinning interventions to reduce sexual violence in armed conflict: A realist-informed systematic review. Confl. Health 2015, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tappis, H.; Freeman, J.; Glass, N.; Doocy, S. Effectiveness of Interventions, Programs and Strategies for Gender-based Violence Prevention in Refugee Populations: An Integrative Review. PLoS Curr. 2016, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Zimmerman, C.; Watss, C. Preventing violence against women and girls in conflict. Lancet 2014, 383, 2021–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurman, T.A.; Trappler, R.M.; Acosta, A.; McCray, P.A.; Cooper, C.M.; Goodsmith, L. “By seeing with our own eyes, it can remain in our mind”: Qualitative evaluation findings suggest the ability of participatory video to reduce gender-based violence in conflict-affected settings. Health Educ. Res. 2014, 29, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ID- Article | Authors and Year | Sample | Origin of Study | Assessment Objective | Instruments | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Robertson C.L., Halcon L., Savik K., Johnson D., (2006) [49] | N = 458 (M = 200; F = 258) | Somalia and South Central Ethiopia | PTSD (Trauma and Torture) | PCL-C | High levels of PTSD symptoms were found in women with many children. |

| 2. | Reedwood-Campbell L., Thind H., Howard M., (2008) [50] | N = 85 F | Kosovo | PTSD | HTQ | A fourth of the population scored high in PTSD. |

| 3. | Vojvoda D., Weine S.M., McGlashan T. (2008) [51] | N = 21 (M = 12; F = 9) | Bosnia | PTSD | PSS | Scores for PTSD severity were higher in women. A significant difference was observed at the three-and-a-half-year follow-up point. |

| 4. | Johnson K., Scott J., Rughita B. (2010) [52] | N = 998 (405 M; 593 F) | Democratic Republic of Congo | PTSD (Sexual violence) | PSS-I | The results showed that 50.1% of the population met the criteria of PTSD, with the highest scores being among women, and 70.2% of them met criteria based on experiences of sexual violence, with scores being higher among women. |

| 5. | Schalinski L., Elbert T., Schauer M. (2011) [53] | N = 53 F | Democratic Republic of Congo | PTSD and disassociation | PSS-I | Thirty-six subjects met all the criteria for PTSD and sexual assault was the most frequent traumatic event. The greater the disassociation and the higher the number of traumatic events, the greater the severity of PTSD. |

| 6. | Ssenyonga J., Owens V., Olema D.K. (2012) [54] | N = 89 (M = 33; F = 56) | Democratic Republic of Congo | PTSD | PSD | Forty-four subjects suffered PTSD, of which 33 were women who scored higher than men in intrusion, evasion, and hyper-activation symptoms and in general severity of PTSD. |

| 7. | Morof D.F., Sami S., Mangeni M (2014) [55] | N= 117 F | Democratic Republic of Congo and Somalia | PTSD (sexual and/or physical violence) | HTQ | Eighty-three women had PTSD symptoms (71% of the population). |

| 8. | Schalinski I., Moran J., Schauer M… (2014) [56] | N = 50 F (PTSD = 33; NO PTSD = 17) | Far and Middle East, The Balkans, Africa and India | PTSD and Disassociation | CAPS; Shut- D; IAPS. | Patients with PTSD displayed intrusive memories, while the control group (NO PTSD) did not report having such memories. The women with the most severe PTSD symptoms displayed greater disassociation. |

| 9. | Alpak G., Unal A. Bulbul F., (2015) [57] | N = 352 (M = 179; F = 173) | Syria and Turkey | PTSD | DSM-IV-TR | One hundred and eighteen of the participants were diagnosed with PTSD. Eleven of them suffered from acute PTSD, 105 from chronic PTSD and 2 from late onset PTSD. |

| 10. | Haldane J, Nickerson A. (2016) [58] | N = 91 (M = 60; F = 31) | Iran, Sri Lanka; Afghanistan and Iraq | PTSD (impact of gender in interpersonal non-interpersonal traumatic experiences) | HTQ | A significant relation was found between non-interpersonal trauma and symptoms of PTSD. In women, a relation was observed between PTSD symptoms and traumatic interpersonal events, while in men the significant association was between PTSD symptoms and non-interpersonal traumatic events. |

| 11. | Rometsch-Ogioun C., Denkinger J.K., Windthorst P., … (2018) [42] | - | Northern Iraq (Yazidí women) | Factors related with past histories of trauma. | Questionnaire designed by psychologists and psychologists | The psychological symptoms identified as particularly significant were nightmares, insomnia and depression. |

| 12. | Mhlongo M.D., Tomita A., Thela L. (2018) [59] | N = 157 | Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Mozambique, Ruanda, Uganda, Malawi and Zimbabwe. | Relation between experience of traumatic event and PTSD. | LEC; HTQ | Exposure to a higher number of traumatic events was associated with a higher likelihood to be at risk for PTSD. Exposure to sexual trauma was associated with a higher likelihood to be at risk for PTSD in women. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vallejo-Martín, M.; Sánchez Sancha, A.; Canto, J.M. Refugee Women with a History of Trauma: Gender Vulnerability in Relation to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094806

Vallejo-Martín M, Sánchez Sancha A, Canto JM. Refugee Women with a History of Trauma: Gender Vulnerability in Relation to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094806

Chicago/Turabian StyleVallejo-Martín, Macarena, Ana Sánchez Sancha, and Jesús M. Canto. 2021. "Refugee Women with a History of Trauma: Gender Vulnerability in Relation to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 9: 4806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094806

APA StyleVallejo-Martín, M., Sánchez Sancha, A., & Canto, J. M. (2021). Refugee Women with a History of Trauma: Gender Vulnerability in Relation to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094806