Effects of a Massage Protocol in Tensiomyographic and Myotonometric Proprieties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

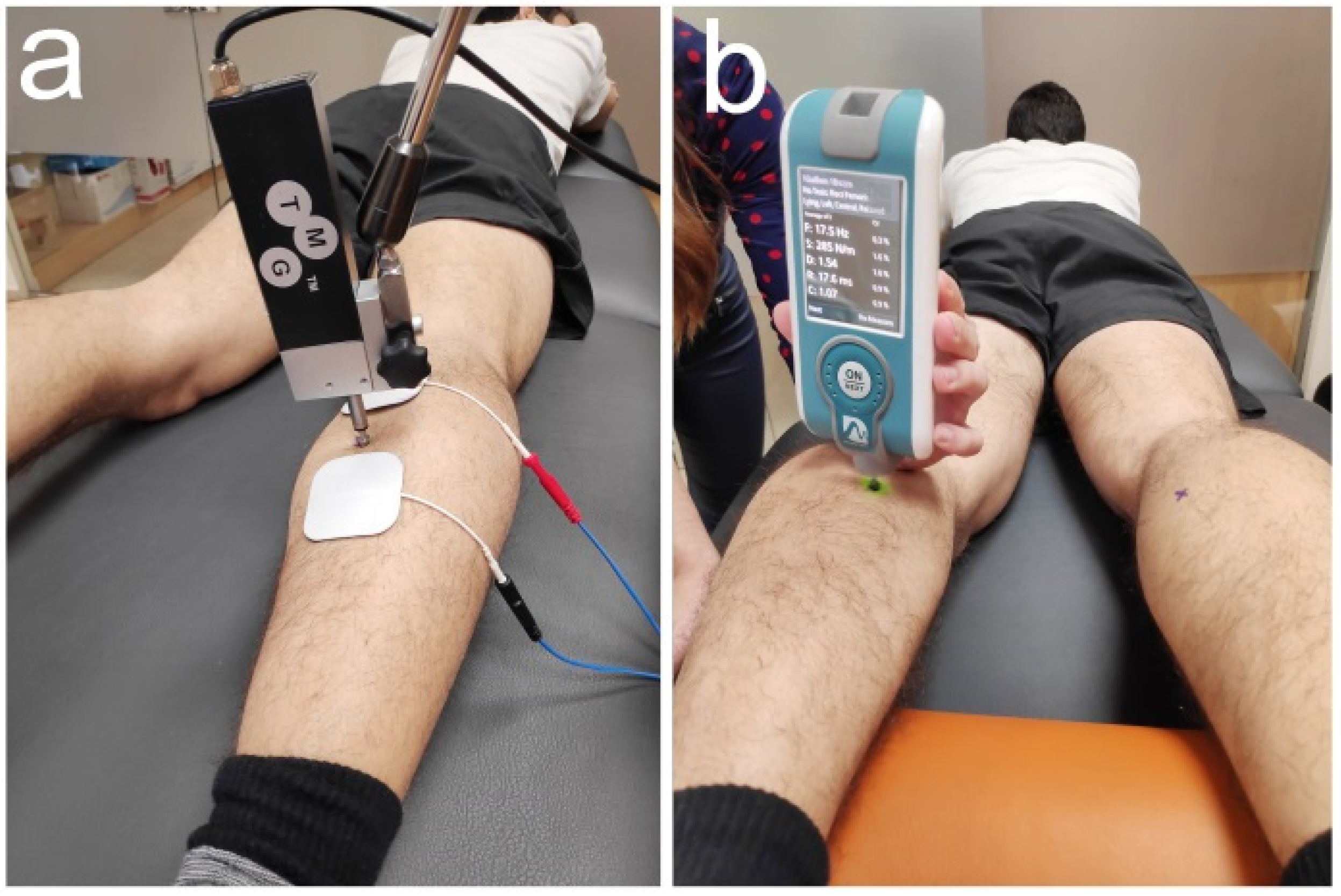

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Callaghan, M.J. The role of massage in the management of the athlete: A review. Br. J. Sports Med. 1993, 27, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goats, G.C. Massage—The scientific basis of an ancient art: Part 1. The techniques. Br. J. Sports Med. 1994, 28, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassar, M.-P. Handbook of Clinical Massage: A Complete Guide for Students and Professionals; Churchill Livingstone: London, UK, 2004; ISBN 9780443073496. [Google Scholar]

- Draper, D.O.; Tessier, D.G. Sports Massage: An Overview. Athl. Ther. Today 2005, 10, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D. Warm Up I: Potential mechanisms and the effects of passive warm up on exercise performance. Sport Med. 2003, 33, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerapong, P.; Hume, P.A.; Kolt, G.S. The mechanisms of massage and effects on performance, muscle recovery and injury prevention. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C.P.; Woodruff, L.D.; Wright, L.L.; Donatelli, R. The immediate effects of manual massage on power-grip performance after maximal exercise in healthy adults. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2005, 11, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKechnie, G.J.; Young, W.B.; Behm, D.G. Acute effects of two massage techniques on ankle joint flexibility and power of the plantar flexors. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2007, 6, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hopper, D.; Conneely, M.; Chromiak, F.; Canini, E.; Berggren, J.; Briffa, K. Evaluation of the effect of two massage techniques on hamstring muscle length in competitive female hockey players. Phys. Ther. Sport 2005, 6, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Newton, M.; Sacco, P.; Nosaka, K. Effects of massage on delayed-onset muscle soreness, swelling, and recovery of muscle function. J. Athl. Train. 2005, 40, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Mauntel, T.C.; Clark, M.A.; Padua, D.A. Effectiveness of myofascial release therapies on physical performance measurements: A systematic review. Athl. Train. Sports Health Care 2014, 6, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, R.; Langer, R.; Vacanti, J.; Atala, A. Principles of Tissue Engineering; Elsevier Inc.: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Bule, M.L.; Paíno, C.L.; Trillo, M.Á.; Úbeda, A. Electric stimulation at 448 kHz promotes proliferation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 34, 1741–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.A.M.; Rocha, C.; Ferreira, H.T.; Silva, H.N. Lower limb massage in humans increases local perfusion and impacts systemic hemodynamics. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 128, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, R.N.; Hauth, J.M.; Rabena, R. The effect of massage on acceleration and sprint performance in track & field athletes. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2018, 30, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labata-Lezaun, N.; López-De-Celis, C.; Llurda-Almuzara, L.; González-Rueda, V.; Cadellans-Arróniz, A.; Pérez-Bellmunt, A. Correlation between maximal radial muscle displacement and stiffness in gastrocnemius muscle. Physiol. Meas. 2020, 41, 125013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llurda-Almuzara, L.; Pérez-Bellmunt, A.; López-De-Celis, C.; Aiguadé, R.; Seijas, R.; Casasayas-Cos, O.; Labata-Lezaun, N.; Alvarez, P. Normative data and correlation between dynamic knee valgus and neuromuscular response among healthy active males: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Bellmunt, A.; Llurda-Almuzara, L.; Simon, M.; Navarro, R.; Casasayas, O.; López-de-Celis, C. Review article. Neuromuscular response what is it and how to measure it? Phys. Med. Rehabil. J. 2019, 2, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, L. Parameters representing muscle tone, elasticity and stiffness of biceps brachii in healthy older males: Symmetry and within-session reliability using the MyotonPRO. J. Neurol. Disord. 2013, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, C.; Braumann, K.-M.; Reer, R.; Schroeder, J.; Schmidt, T. Reliability of tensiomyography and myotonometry in detecting mechanical and contractile characteristics of the lumbar erector spinae in healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 118, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, K.; Warner, M.; Stokes, M. Symmetry and within-session reliability of mechanical properties of biceps brachii muscles in healthy young adult males using the MyotonPRO device. Work. Pap. Health Sci. 2013, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ditroilo, M.; Hunter, A.M.; Haslam, S.; De Vito, G. The effectiveness of two novel techniques in establishing the mechanical and contractile responses of biceps femoris. Physiol. Meas. 2011, 32, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-García, O.; Cuba-Dorado, A.; Álvarez-Yates, T.; Carballo-López, J.; Iglesias-Caamaño, M. Clinical utility of tensiomyography for muscle function analysis in athletes. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2019, 10, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisloff, U.; Castagna, C.; Helgerud, J.; Jones, R.; Hoff, J. Strong correlation of maximal squat strength with sprint performance and vertical jump height in elite soccer players. Br. J. Sports Med. 2004, 38, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescovi, J.D.; McGuigan, M.R. Relationships between sprinting, agility, and jump ability in female athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Wilson, G.; Byrne, C. Relationship between strength qualties and performance in standing and run-up vertical jumps. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 1999, 39, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cook, R.J.; Dickens, B.M.; Fathalla, M.F. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.L.; Whitehead, A.L.; Julious, S.A. Guidance for using pilot studies to inform the design of intervention trials with continuous outcomes. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 10, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, G.J.; Chung, C.B.; Lektrakul, N.; Azocar, P.; Botte, M.J.; Coria, D.; Bosch, E.; Resnick, D. Tennis leg: Clinical US study of 141 patients and anatomic investigation of four cadavers with MR imaging and US. Radiology 2002, 224, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, E.; Lago-Peñas, C.; Lago-Ballesteros, J. Tensiomyography of selected lower-limb muscles in professional soccer players. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2012, 22, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Diaz, P.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; Ramon, S.; Marin, M.; Steinbacher, G.; Rius, M.; Seijas, R.; Ballester, J.; Cugat, R. Comparison of tensiomyographic neuromuscular characteristics between muscles of the dominant and non-dominant lower extremity in male soccer players. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2014, 24, 2259–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruyn, E.C.; Watsford, M.L.; Murphy, A.J. Validity and reliability of three methods of stiffness assessment. J. Sport Health Sci. 2016, 5, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.N.; Li, Y.P.; Liu, C.L.; Zhang, Z.J. Assessing the elastic properties of skeletal muscle and tendon using shearwave ultrasound elastography and MyotonPRO. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzini, M.; Mannion, A.F. Reliability of a new, hand-held device for assessing skeletal muscle stiffness. Clin. Biomech. 2003, 18, 459–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viir, R.; Laiho, K.; Kramarenko, J.; Mikkelsson, M. Repeatability of trapezius muscle tone assessment by a myometric method. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2006, 6, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, L.-L.; Wu, C.-Y.; Lin, K.-C. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of myotonometric measurement of muscle tone, elasticity, and stiffness in patients with stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2012, 93, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyapong-Badu, S.; Aird, L.; Bailey, L.; Mooney, K.; Mullix, J.; Warner, M.; Samuel, D.; Stokes, M. Interrater reliability of muscle tone, stiffness and elasticity measurements of rectus femoris and biceps brachii in healthy young and older males. Work. Pap. Health Sci. 2013, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, M.J.; Bryant, A.L.; Bower, W.F.; Frawley, H.C. Myotonometry reliably measures muscle stiffness in the thenar and perineal muscles. Physiother. Can. 2017, 69, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Bernal, M.-I.; Heredia-Rizo, A.M.; Gonzalez-Garcia, P.; Cortés-Vega, M.-D.; Casuso-Holgado, M.J. Validity and reliability of myotonometry for assessing muscle viscoelastic properties in patients with stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Morales, M.; Fernández-Lao, C.; Ariza-García, A.; Toro-Velasco, C.; Winters, M.; Díaz-Rodríguez, L.; Cantarero-Villanueva, I.; Huijbregts, P.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C. Psychophysiological effects of preperformance massage before isokinetic exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Križaj, D.; Šimunič, B.; Žagar, T. Short-term repeatability of parameters extracted from radial displacement of muscle belly. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2008, 18, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tous-Fajardo, J.; Moras, G.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, S.; Usach, R.; Doutres, D.M.; Maffiuletti, N.A. Inter-rater reliability of muscle contractile property measurements using non-invasive tensiomyography. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2010, 20, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, L.D.; Cosma, G.G.H.; Cernaianu, S.M.; Marin, M.N.; Rusu, P.F.A.; Ciocănescu, D.P.; Neferu, F.N. Tensiomyography method used for neuromuscular assessment of muscle training. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2013, 10, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haff, G.G.; Whitley, A.; Potteiger, J.A. A brief review: Explosive exercises and sports performance. Strength Cond. J. 2001, 23, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loturco, I.; Gil, S.; Laurino, C.F.D.S.; Roschel, H.; Kobal, R.; Abad, C.C.C.; Nakamura, F.Y. Differences in muscle mechanical properties between elite power and endurance athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 1723–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunič, B.; Pisot, R.; Rittweger, J.; Degens, H. Age-related slowing of contractile properties differs between power, endurance, and nonathletes: A tensiomyographic assessment. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2018, 73, 1602–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Manso, J.M.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, D.; Rodríguez-Matoso, D.; De Saa, Y.; Sarmiento, S.; Quiroga, M. Assessment of muscle fatigue after an ultra-endurance triathlon using tensiomyography (TMG). J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Manso, J.M.; Rodríguez-Matoso, D.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, D.; Sarmiento, S.; de Saa, Y.; Calderón, J. Effect of cold-water immersion on skeletal muscle contractile properties in soccer players. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 90, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeder, J.; Gissane, C.; Van Someren, K.; Gregson, W.; Howatson, G. Cold water immersion and recovery from strenuous exercise: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alentorn-Geli, E.; Alvarez-Diaz, P.; Ramon, S.; Marin, M.; Steinbacher, G.; Boffa, J.J.; Cuscó, X.; Ballester, J.; Cugat, R. Assessment of neuromuscular risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament injury through tensiomyography in male soccer players. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2014, 23, 2508–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtarzadeh, H.; Yeow, C.H.; Goh, J.C.H.; Oetomo, D.; Malekipour, F.; Lee, P.V.-S. Contributions of the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles to the anterior cruciate ligament loading during single-leg landing. J. Biomech. 2013, 46, 1913–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, J.J.; Faust, A.F.; Chu, Y.-H.; Chao, E.Y.; Cosgarea, A.J. The soleus muscle acts as an agonist for the anterior cruciate ligament: An in vitro experimental study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2003, 31, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubac, D.; Paravlić, A.; Koren, K.; Felicita, U.; Šimunič, B. Plyometric exercise improves jumping performance and skeletal muscle contractile properties in seniors. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2019, 19, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pišot, R.; Narici, M.V.; Šimunič, B.; De Boer, M.; Seynnes, O.; Jurdana, M.; Biolo, G.; Mekjavić, I.B. Whole muscle contractile parameters and thickness loss during 35-day bed rest. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simola, R.; Álvaro, D.P.; Raeder, C.; Wiewelhove, T.; Kellmann, M.; Meyer, T.; Pfeiffer, M.; Ferrauti, A. Muscle mechanical properties of strength and endurance athletes and changes after one week of intensive training. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2016, 30, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-De-Celis, C.; Pérez-Bellmunt, A.; Bueno-Gracia, E.; Fanlo-Mazas, P.; Zárate-Tejero, C.A.; Llurda-Almuzara, L.; Arróniz, A.C.; Rodriguez-Rubio, P.R. Effect of diacutaneous fibrolysis on the muscular properties of gastrocnemius muscle. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masugi, Y.; Obata, H.; Inoue, D.; Kawashima, N.; Nakazawa, K. Neural effects of muscle stretching on the spinal reflexes in multiple lower-limb muscles. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariyildiz, M.; Karacan, I.; Rezvani, A.; Ergin, O.; Cidem, M. Cross-education of muscle strength: Cross-training effects are not confined to untrained contralateral homologous muscle. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2011, 21, e359–e364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, T.J.; Herbert, R.D.; Munn, J.; Lee, M.; Gandevia, S.C. Contralateral effects of unilateral strength training: Evidence and possible mechanisms. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 101, 1514–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, J.; Herbert, R.D.; Gandevia, S.C. Contralateral effects of unilateral resistance training: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004, 96, 1861–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | N (%)—Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Sex | 10 women (33.3%); 20 men (66.7%) |

| Age (years) | 23.87 (6.17) |

| Weight (kg) | 69.23 (1.76) |

| Height (cm) | 174 (9.00) |

| Baseline | Post-Intervention | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-Value | Effect Size | |

| Experimental Limb | ||||||

| Tensiomyography | Td | 21.16 (1.93) | 21.64 (1.83) | 0.48 (1.64) | 0.119 a | 0.26 |

| Tc | 27.01 (8.53) | 33.23 (11.64) | 6.21 (10.36) | 0.002 b * | 0.61 | |

| Ts | 232.24 (81.34) | 210.21 (56.74) | −22.03 (82.97) | 0.237 b | 0.31 | |

| Tr | 65.92 (59.38) | 53.91 (20.86) | −12.01 (51.78) | 0.304 b | 0.27 | |

| Dm | 3.96 (1.11) | 4.26 (1.27) | 0.29 (0.86) | 0.102 b | 0.25 | |

| Myotonometry | Tone | 15.13 (1.44) | 14.69 (1.33) | −0.43 (0.55) | 0.001 a * | 0.32 |

| Stiffness | 260.88 (27.44) | 252.55 (28.43) | −8.33 (11.67) | 0.002 b * | 0.30 | |

| Relaxation | 20.93 (2.08) | 21.48 (1.90) | 0.56 (1.05) | 0.007 a * | 0.28 | |

| Control Limb | ||||||

| Tensiomyography | Td | 20.57 (1.72) | 20.96 (1.81) | 0.39 (1.27) | 0.106 a | 0.22 |

| Tc | 25.97 (8.93) | 27.72 (10.31) | 1.75 (8.59) | 0.049 b * | 0.18 | |

| Ts | 203.43 (45.61) | 208.02 (31.40) | 4.59 (40.82) | 0.060 b | 0.12 | |

| Tr | 44.22 (17.56) | 56.13 (30.88) | 11.92 (23.68) | 0.008 b * | 0.47 | |

| Dm | 4.31 (1.80) | 4.22 (1.91) | −0.09 (0.71) | 0.213 b | 0.05 | |

| Myotonometry | Tone | 15.10 (1.31) | 15.03 (1.23) | −0.06 (0.53) | 0.506 a | 0.06 |

| Stiffness | 259.92 (25.75) | 255.87 (24.76) | −4.05 (9.40) | 0.043 a * | 0.16 | |

| Relaxation | 20.89 (2.25) | 21.08 (2.19) | 0.19 (0.60) | 0.090 a | 0.09 | |

| Variable | Mean (SD) | p-Value | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensiomyography | Td | 0.09 (1.76) | 0.098 b | 0.37 |

| Tc | 4.46 (10.25) | 0.038 b * | 0.50 | |

| Ts | −26.61 (85.87) | 0.019 b * | 0.05 | |

| Tr | −23.93 (54.94) | 0.117 b | 0.08 | |

| Dm | 0.38 (1.00) | 0.673 b | 0.03 | |

| Myotonometry | Tone | −0.37 (0.80) | 0.048 b * | 0.27 |

| Stiffness | −4.28 (12.52) | 0.123 a | 0.13 | |

| Relaxation | 0.36 (1.09) | 0.101 a | 0.20 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Bellmunt, A.; Labata-Lezaun, N.; Llurda-Almuzara, L.; Rodríguez-Sanz, J.; González-Rueda, V.; Bueno-Gracia, E.; Celik, D.; López-de-Celis, C. Effects of a Massage Protocol in Tensiomyographic and Myotonometric Proprieties. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3891. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083891

Pérez-Bellmunt A, Labata-Lezaun N, Llurda-Almuzara L, Rodríguez-Sanz J, González-Rueda V, Bueno-Gracia E, Celik D, López-de-Celis C. Effects of a Massage Protocol in Tensiomyographic and Myotonometric Proprieties. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):3891. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083891

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Bellmunt, Albert, Noé Labata-Lezaun, Luis Llurda-Almuzara, Jacobo Rodríguez-Sanz, Vanessa González-Rueda, Elena Bueno-Gracia, Derya Celik, and Carlos López-de-Celis. 2021. "Effects of a Massage Protocol in Tensiomyographic and Myotonometric Proprieties" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 3891. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083891

APA StylePérez-Bellmunt, A., Labata-Lezaun, N., Llurda-Almuzara, L., Rodríguez-Sanz, J., González-Rueda, V., Bueno-Gracia, E., Celik, D., & López-de-Celis, C. (2021). Effects of a Massage Protocol in Tensiomyographic and Myotonometric Proprieties. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 3891. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083891