First Surveillance of Violence against Women during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from “Niguarda” Hospital in Milan, Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

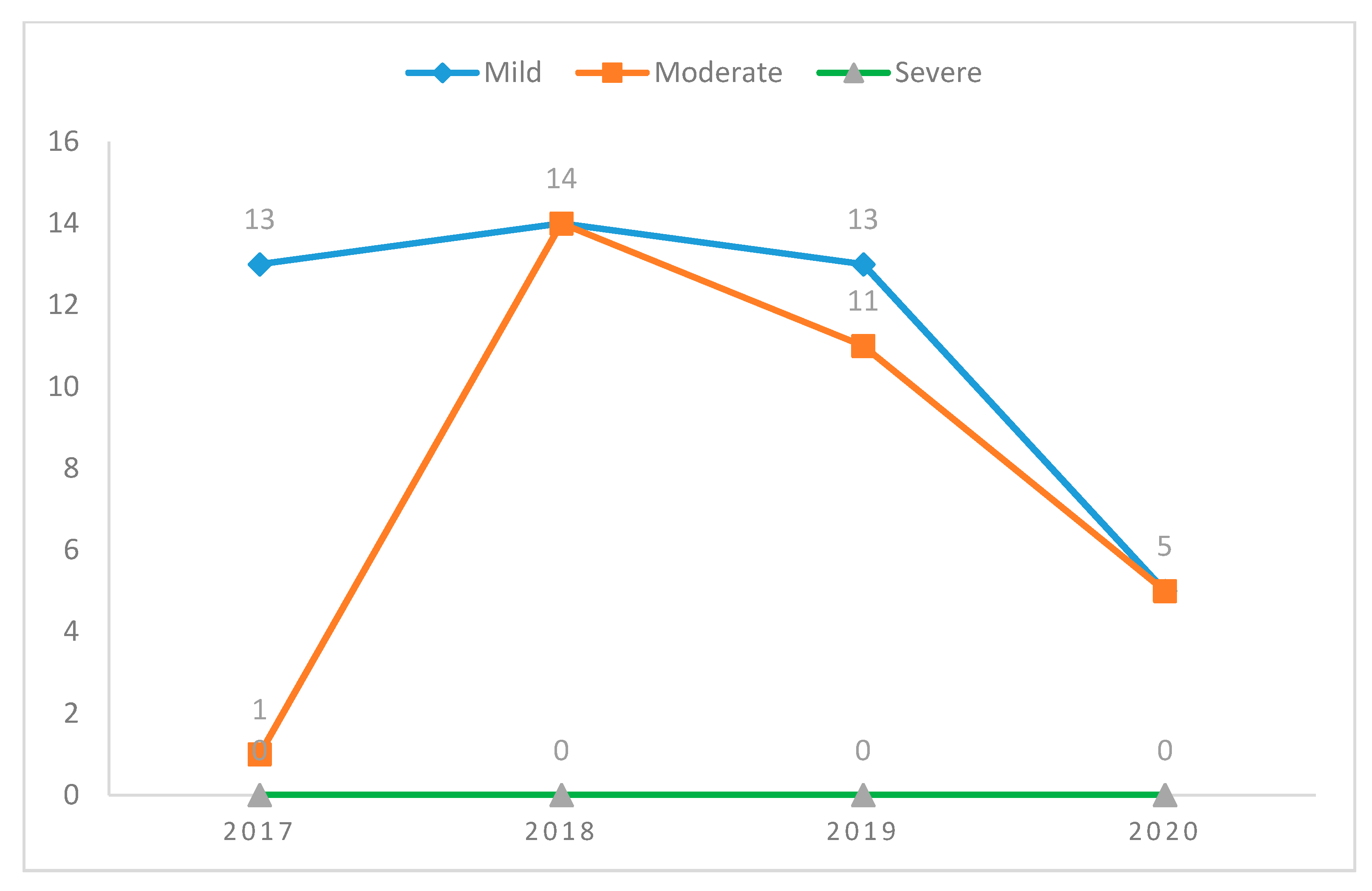

- (1)

- Aggressions, Beatings, Ecchymosis: this category includes hospital admissions without obvious symptoms (therefore, only a report of aggression), bruises and “light” signs of beatings, etc.

- (2)

- Multiple bruises, wounds, bites: include obvious wounds and signs of aggression, sometimes accompanied by fractures of various sizes.

- (3)

- Head injuries: includes head injuries of any extent.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Potenza, S.; Carella, V.; Feola, A.; Marsella, L.T.; Marella, G.L. Femicide in a central Italy district (Southern Latium) in the period 1998–2018. Minerva Psichiatr. 2021, 61, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico (MISE). Femminicidio. Available online: https://www.mise.gov.it/images/stories/documenti/FEMMINICIDIO_per_web.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale. Allegato 2. Available online: https://www.esteri.it/mae/approfondimenti/20090827_allegato2_it.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Acquadro Maran, D.; Varetto, A.; Corona, I.; Tirassa, M. Characteristics of the stalking campaign: Consequences and coping strategies for men and women that report their victimization to police. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci, G.; Pallotta, G.; Sirignano, A.; Amenta, F.; Nittari, G. Consequences of COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy: Medical responsibilities and governmental measures. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 588852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolcato, M.; Aurilio, M.T.; Aprile, A.; Di Mizio, G.; Della Pietra, B.; Feola, A. Take-home messages from the COVID-19 pandemic: Strengths and pitfalls of the italian national health service from a medico-legal point of view. Healthcare 2021, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Campanozzi, L.L.; Nittari, G.; Sirignano, A. Telemedicine as a concrete response to covids-19 pandemic. [La telemedicina come una risposta concreta alla pandemia da sars-cov-2]. Riv. Ital. Med. Leg. Dirit. Campo Sanit. 2020, 2, 927–935. [Google Scholar]

- Yahya, A.S.; Khawaja, S.; Chukwuma, J. Association of COVID-19 with Intimate Partner Violence. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord [Internet]. 7 May 2020. Available online: https://www.psychiatrist.com/pcc/covid-19/intimate-partner-violence-and-covid (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Peterman, A.; O’Donnell, M. COVID-19 and Violence against womEn and Children: A Second Research Round Up. Cent Glob Dev [Internet]. 2020. Available online: https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/covid-19-and-violence-against-women-and-children-second-research-round.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Devries, K.M.; Mak, J.Y.T.; García-Moreno, C.; Petzold, M.; Child, J.C.; Falder, G.; Lim, S.; Bacchus, L.J.; Engell, R.E.; Rosenfeld, L.; et al. The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science 2013, 340, 1527–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöckl, H.; Devries, K.; Rotstein, A.; Abrahams, N.; Campbell, J.; Watts, C.; Moreno, C.G. The global prevalence of intimate partner homicide: A systematic review. Lancet 2013, 382, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence [Internet]. 2013. Available online: www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Bogdanović, M.; Atanasijević, T.; Popović, V.; Mihailović, Z.; Radnić, B.; Durmić, T. Is the role of forensic medicine in the covid-19 pandemic underestimated? Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2020, 17, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roux, C.; Weyermann, C. Can forensic science learn from the COVID-19 crisis? Forensic Sci. Int. 2020, 316, 110503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barranco, R.; Ventura, F. The role of forensic pathologists in coronavirus disease 2019 infection: The importance of an interdisciplinary research. Med. Sci. Law. 2020, 60, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zara, G.; Gino, S. Intimate partner violence and its escalation into femicide. Frailty thy name is “Violence against Women”. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence. Available online: https://www.coe.int/fr/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/090000168008482e (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- World Health Organization. Violence against Women. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Violence against Women: An EU-Wide Survey. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2014-vaw-survey-main-results-apr14_en.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- ISTAT. La Violenza Contro le Donne Dentro e Fuori la Famiglia. 2020. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/161716 (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Ertan, D.; El-Hage, W.; Thierrée, S.; Javelot, H.; Hingray, C. COVID-19: Urgency for distancing from domestic violence. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2020, 11, 1800245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usher, K.; Bhullar, N.; Durkin, J.; Gyamfi, N.; Jackson, D. Family violence and COVID-19: Increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, A.M. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2020, 2, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, D. Investigating the increase in domestic violence post disaster: An australian case study. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 2333–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreschi, C.; Da Broi, U.; Zamai, V.; Palese, F. Medico legal and epidemiological aspects of femicide in a judicial district of north eastern Italy. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2016, 39, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanni, E.; Maiese, A.; Gitto, L.; Falco, P.; Maiese, A.; Bolino, G. Femicide in Italy: National scenario and presentation of four cases. Med. Leg. J. 2014, 82, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zara, G.; Freilone, F.; Veggi, S.; Biondi, E.; Ceccarelli, D.; Gino, S. The medicolegal, psycho-criminological, and epidemiological reality of intimate partner and non-intimate partner femicide in North-West Italy: Looking backwards to see forwards. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2019, 133, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roesch, E.; Amin, A.; Gupta, J.; García-Moreno, C. Violence against women during covid-19 pandemic restrictions. BMJ 2020, 369, m1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, O.R.; Vale, D.B.; Rodrigues, L.; Surita, F.G. Violence against women during the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2020, 151, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | N° Hospitalization | Average Age of Patients | N(%) Italian Patients; N(%) Foreign Patients | Average Prognosis Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 14 | 39.07 | 7 (50%); 7 (50%) | 11.07 days |

| 2018 | 28 | 36.68 | 15 (53.57%); 13(46.43%) | 15.16 days |

| 2019 | 24 | 35.83 | 8 (33.33%); 16 (66.67%) | 12.70 days |

| 2020 | 10 | 47.50 | 5 (50%); 5 (50%) | 21.75 days |

| Diagnosis | 2017 N Cases (%) | 2018 N Cases (%) | 2019 N Cases (%) | 2020 N Cases (%) | Total N Cases (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attacks, Beatings, Ecchymosis | 4 (28.56%) | 7 (25%) | 8 (33.33%) | 2 (20%) | 21 (15.96%) |

| Multiple bruises, injured, Fractures | 7 (50%) | 17 (60.71%) | 13 (54.17%) | 6 (60%) | 43 (56.58%) |

| Head trauma | 3 (21.44%) | 4 (14.29%) | 3 (12.5%) | 2 (20%) | 12 (27.46%) |

| All diagnoses | 14 | 28 | 24 | 10 | 76 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nittari, G.; Sagaro, G.G.; Feola, A.; Scipioni, M.; Ricci, G.; Sirignano, A. First Surveillance of Violence against Women during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from “Niguarda” Hospital in Milan, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073801

Nittari G, Sagaro GG, Feola A, Scipioni M, Ricci G, Sirignano A. First Surveillance of Violence against Women during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from “Niguarda” Hospital in Milan, Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(7):3801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073801

Chicago/Turabian StyleNittari, Giulio, Getu Gamo Sagaro, Alessandro Feola, Mattia Scipioni, Giovanna Ricci, and Ascanio Sirignano. 2021. "First Surveillance of Violence against Women during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from “Niguarda” Hospital in Milan, Italy" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 7: 3801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073801

APA StyleNittari, G., Sagaro, G. G., Feola, A., Scipioni, M., Ricci, G., & Sirignano, A. (2021). First Surveillance of Violence against Women during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from “Niguarda” Hospital in Milan, Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073801