Experiences and Perceptions of Trans and Gender Non-Binary People Regarding Their Psychosocial Support Needs: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

- (i)

- identify the experiences and perceptions of trans and non-binary people regarding their psychosocial needs,

- (ii)

- establish the psychosocial interventions and supports that are available to people who identify as trans and non-binary?

- (iii)

- highlight the best practice examples that exist.

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Synthesis

2.6. Quality Assessment

- Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question?

- Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question?

- Are the findings adequately derived from the data?

- Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data?

- Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation?

3. Results

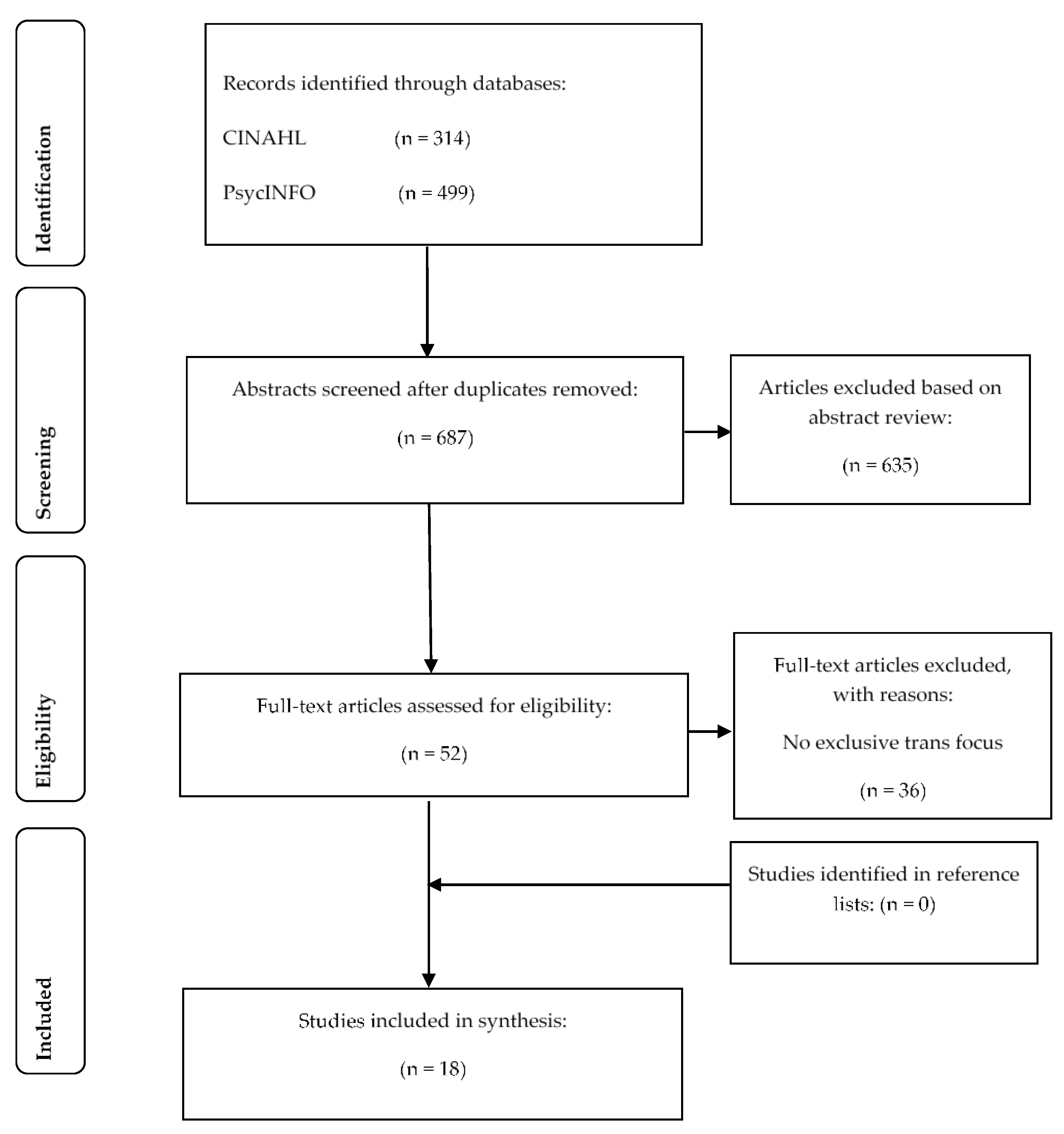

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Thematic Analysis

3.3.1. Stigma, Discrimination and Marginalisation

3.3.2. Transgender Affirmative Experiences

3.3.3. Formal and Informal Supports

3.3.4. Healthcare Access

4. Discussion

4.1. Policy

4.2. Education and Practice Development

4.3. Practice

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Devor, A.; Thomas, A.H. Transgender: A Reference Handbook; ABCCLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stonewall Glossary of Terms. Available online: https://www.stonewall.org.uk/help-advice/faqs-and-glossary/glossary-terms#t (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Williams Institute. Subpopulations: Transgender People. Available online: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/subpopulations/transgender-people/ (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Stonewall. Available online: https://www.stonewall.org.uk/truth-about-trans#trans-people-britain (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- McLemore, K. A Minority Stress Perspective on Transgender Individuals’ Experiences with Misgendering. Stigma Health 2018, 3, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.K.H.; Treharne, G.J.; Ellis, S.J.; Schmidt, J.M.; Veale, J.F. Gender Minority Stress: A Critical Review. J. Homosex. 2019, 67, 1471–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, J.L.; Brown, T.N.; Haas, A.P. Suicide Thoughts and Attempts among Transgender Adults: Findings from the 2015 US Transgender Survey; Williams Institute UCLA: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bränström, R.; Pachankis, J.E. Reduction in mental health treatment utilization among transgender individuals after gender-affirming surgeries: A total population study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peitzmeier, S.M.; Malik, M.; Kattari, S.K.; Marrow, E.; Stephenson, R.; Agénor, M.; Reisner, S.L. Intimate partner violence in transgender populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and correlates. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, e1–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.; Gilchrist, G. Prevalence and correlates of substance use among transgender adults: A systematic review. Addict. Behav. 2020, 111, 106544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, E.; Brown, M.J. Homeless experiences and support needs of transgender people: A systematic review of the international evidence. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.M.; Frey, L.M.; Stage, D.L.; Cerel, J. Exploring lived experience in gender and sexual minority suicide attempt survivors. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2018, 88, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, J.D.; Jackman, K.B.; Barucco, R.; Dworkin, J.D.; Dolezal, C.; Navalta, T.V.; Belloir, J.; Bockting, W.O. Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary Individuals Engaged in a Longitudinal Cohort Study. J. Homosex. 2021, 68, 592–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarrett, B.A.; Peitzmeier, S.M.; Restar, A.; Adamson, T.; Howell, S.; Baral, S.; Beckham, S.W. Gender-affirming care, mental health, and economic stability in the time of COVID-19: A global cross-sectional study of transgender and non-binary people. medRxiv 2020. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.11.02.20224709v2 (accessed on 2 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M.D.; Zervos, M.J.; Barone, C.J., II; Johnson, C.C.; Joseph, C.L. The mental health of transgender youth: Advances in understanding. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderssen, N.; Sivertsen, B.; Lønning, K.J.; Malterud, K. Life satisfaction and mental health among transgender students in Norway. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kcomt, L.; Gorey, K.M.; Barrett, B.J.; McCabe, S.E. Healthcare avoidance due to anticipated discrimination among transgender people: A call to create trans-affirmative environments. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 11, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, C.A.; Poquiz, J.L.; Janssen, A.; Chen, D. Evidence-based psychological practice for transgender and non-binary youth: Defining the need, framework for treatment adaptation, and future directions. Evid. Based Pract. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 5, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applegarth, G.; Nuttall, J. The lived experience of transgender people of talking therapies. Int. J. Transgenderism 2016, 17, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, S.L.; Sinnard, M.T.; Hoyt, W.T. Longitudinal effects of psychotherapy with transgender and nonbinary clients: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Psychotherapy 2020. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/openview/294f47004ad908c6531f7a89feea9987/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=496309 (accessed on 25 January 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbey, D.; Morgan, H.; Lin, A.; Perry, Y. Effectiveness, Acceptability, and Feasibility of Digital Health Interventions for LGBTIQ+ Young People: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Y.; Strauss, P.; Lin, A. Online interventions for the mental health needs of trans and gender diverse young people. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, E.; Israel, T. Psychological Interventions Promoting Resilience among Transgender Individuals: Transgender Resilience Intervention Model (TRIM). Couns. Psychol. 2018, 46, 632–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review Software, Melbourne, Australia. 2021. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Terry, G.; Hayfield, N.; Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Rao, T.S.S. “The Graying Minority”: Lived Experiences and Psychosocial Challenges of Older Transgender Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic in India, A Qualitative Exploration. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 604472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, K.E. Seeking Support: Transgender Client Experiences with Mental Health Services. J. Fem. Fam. Ther. 2013, 25, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, N.; McCann, E. A phenomenological exploration of transgender people’s experiences of mental health services in Ireland. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 29, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughto, J.M.W.; Clark, K.A.; Altice, F.L.; Reisner, S.L.; Kershaw, T.S.; Pachankis, J.E. Creating, reinforcing, and resisting the gender binary: A qualitative study of transgender women’s healthcare experiences in sex-segregated jails and prisons. Int. J. Prison. Health 2018, 14, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.C.; Leblanc, A.J.; Sterzing, P.R.; Deardorff, J.; Antin, T.; Bockting, W.O. Trans adolescents’ perceptions and experiences of their parents’ supportive and rejecting behaviors. J. Couns. Psychol. 2020, 67, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, D.; Martyr, M.A.; Mitchell, T.A.; Arthur, T.; Koch, J.M. Recommendations from Transgender Healthcare Consumers in Rural Areas. Transgender Health 2018, 3, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lykens, J.E.; Leblanc, A.J.; Bockting, W.O. Healthcare Experiences among Young Adults Who Identify as Genderqueer or Nonbinary. LGBT Health 2018, 5, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, E. People who are transgender: Mental health concerns. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 22, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizock, L.; Lundquist, C. Missteps in psychotherapy with transgender clients: Promoting gender sensitivity in counseling and psychological practice. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2016, 3, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritterbusch, A.E.; Salazar, C.C.; Correa, A. Stigma-related access barriers and violence against trans women in the Colombian healthcare system. Glob. Public Health 2018, 13, 1831–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansfaçon, A.P.; Hébert, W.; Lee, E.O.J.; Faddoul, M.; Tourki, D.; Bellot, C. Digging beneath the surface: Results from stage one of a qualitative analysis of factors influencing the well-being of trans youth in Quebec. Int. J. Transgenderism 2018, 19, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.C.; Mann, E.S.; Pfeffer, C.A. Are university health services meeting the needs of transgender college students? A qualitative assessment of a public university. J. Am. Coll. Health 2019, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, P.; Morgan, H.; Toussaint, D.W.; Lin, A.; Winter, S.; Perry, Y. Trans and gender diverse young people’s attitudes towards game-based digital mental health interventions: A qualitative investigation. Internet Interv. 2019, 18, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeir, E.; Jackson, L.A.; Marshall, E.G. Barriers to primary and emergency healthcare for trans adults. Cult. Health Sex. 2018, 20, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Vogelsang, A.C.; Milton, C.; Ericsson, I.; Strömberg, L. ‘Wouldn’t it be easier if you continued to be a guy?’–a qualitative interview study of transsexual persons’ experiences of encounters with healthcare professionals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 3577–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.-H.; Lin, J.; Xiao, W.-J.; Lin, K.-M.; McFarland, W.; Yan, H.-J.; Wilson, E. Identity, stigma, and HIV risk among transgender women: A qualitative study in Jiangsu Province, China. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2019, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real-Quintanar, T.; Robles-García, R.; Medina-Mora, M.E.; Vázquez-Pérez, L.; Romero-Mendoza, M. Qualitative Study of the Processes of Transgender-Men Identity Development. Arch. Med. Res. 2020, 51, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.T. Transmen’s health care experiences: Ethical social work practice beyond the binary. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. 2013, 25, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martos, A.J.; Wilson, P.A.; Meyer, I.H. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health services in the United States: Origins, evolution, and contemporary landscape. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government Equalities Office. LGBT Action Plan; Government Equalities Office: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Sexual Health, Human Rights and the Law; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, S.; Kellett, S.; Simmonds-Buckley, M.; Stockton, D.; Bradbury, A.; Delgadillo, J. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) in the United Kingdom: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 10-years of practice-based evidence. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 60, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, E.; Valaitis, R.; Risdon, C.; Carter, N.; Yost, J. Models of Care and Team Activities in the Delivery of Transgender Primary Care: An Ontario Case Study. Transgender Health 2020, 5, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, E. The integral role of nurses in primary care for transgender people: A qualitative descriptive study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns, M.M.; Lowry, R.; Andrzejewski, J.; Barrios, L.C.; Demissie, Z.; McManus, T.; Rasberry, C.N.; Robin, L.; Underwood, J.M. Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gerwen, O.T.; Jani, A.; Long, D.M.; Austin, E.L.; Musgrove, K.; Muzny, C.A. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and human immunodeficiency virus in transgender persons: A systematic review. Transgender Health 2020, 5, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, M.R.; Jones, A.; Stoy, J. Reducing Barriers: Integrated Collaboration for Transgender Clients. J. Fem. Fam. Ther. 2020, 32, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, E.; Brown, M. The needs of LGBTI+ people within student nurse education programmes: A new conceptualisation. Nurse Educ. Pr. 2020, 47, 102828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinitz, D.J.; Salway, T.; Dromer, E.; Giustini, D.; Ashley, F.; Goodyear, T.; Ferlatte, O.; Kia, H.; Abramovich, A. The scope and nature of sexual orientation and gender identity and expression change efforts: A systematic review protocol. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharek, D.; McCann, E.; Huntley-Moore, S. The design and development of an online education program for families of trans young people. J. LGBT Youth 2020, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, C.H.B.; Bilgin, H.; Uluman, O.T.; Sukut, O.; Yilmaz, S.; Buzlu, S. A Systematic Review of the Discrimination Against Sexual and Gender Minority in Health Care Settings. Int. J. Health Serv. 2020, 50, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonvicini, K.A. LGBT healthcare disparities: What progress have we made? Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 2357–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safer, J.D.; Tangpricha, V. Care of the Transgender Patient. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, ITC1–ITC16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, B.; Liu, Y.; Wilson, A.; Ou, J.; Chen, R. Health care and mental health challenges for transgender individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 564–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, L.; O’Halloran, P.; Oates, J. Investigating the social integration and wellbeing of transgender individuals: A meta-synthesis. Int. J. Transgenderism 2018, 19, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, A.; Craig, S.L.; Alessi, E.J. Affirmative Cognitive Behavior Therapy with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Adults. Psychiatr. Clin. 2017, 40, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, C.; Piquette, N. Counselling transgender individuals: Issues and considerations. Can. Psychol. 2018, 59, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Code | Query | PsycINFO | MEDLINE | CINHAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | transgender or transexual or gender dysphoria or gender non-conforming | 11,514 | 10,711 | 6529 |

| S2 | mental health services or mental health care or psychosocial supports | 178,523 | 87,825 | 144,409 |

| S3 | opinions or views or perceptions or experiences or qualitative | 1,376,790 | 1,825,221 | 700,730 |

| S4 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 | 499 | 141 | 314 |

| S5 | Limiters: academic peer reviewed papers, written in English | 392 | 141 | 308 |

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banerjee & Rao (2021) [27] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Benson (2013) [28] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Delaney & McCann (2020) [29] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Hughto et al. (2018) [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Johnson et al. (2020) [31] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Knutson et al. (2018) [32] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Lykens et al. (2018) [33] | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y | H |

| McCann (2015) [34] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Mizock & Lundquist (2016) [35] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Real-Quintanar et al. (2020) [43] | Y | Y | CT | CT | CT | M |

| Ritterbusch et al. (2018) [36] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Sansfaçon et al. (2018) [37] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Santos et al. (2019) [38] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Strauss et al. (2019) [39] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Taylor (2013) [44] | Y | CT | Y | CT | CT | M |

| Vermeir et al. (2018) [40] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| von Vogelsang et al. (2016) [41] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Yan et al. (2019) [42] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | H |

| Citation and Country | Aim | Sample | Methods | Main Results | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banerjee & Rao (2021) India [27] | To explore the lived experiences and psychosocial challenges of older transgender adults during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. | Transgender individuals (n = 10), aged > 60 years. | In depth individual interviews. Phenomenological analysis. | Categories identified were marginalization, the dual burden of “age” and “gender” and multi-faceted survival threats during the pandemic. Social rituals, spirituality, hope, and acceptance of “gender dissonance” emerged as the main coping factors, whereas their unmet needs were social inclusion, awareness related to COVID-19 and mental health care. | Older aged gender minorities are at increased emotional and social risk during the ongoing pandemic. The need for policy implementation and community awareness about their social welfare is vital to improving their health and well-being. |

| Benson (2013) USA [28] | To critically review historical views of transgender clients and to highlight experiences of transgender clients in therapy. | Transgender individuals (n = 7), aged 24–57 years. | In-depth individual interviews. Feminist phenomenology informed analysis. | Four themes emerged: the purposes transgender clients sought therapy for, problems in practice, therapist reputation, and transgender affirmative therapy. | Mental health professionals need transgender specific training to stand against a history of pathology and acquire the skills and sensitivity needed to best support transgender clients. |

| Delaney & McCann (2020) Ireland [29] | To explore the personal experiences of transgender people with Irish mental health services. | Transgender individuals (n = 4), aged 29–45 years. | Semi-structured individual interviews. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. | Three themes emerged: affirmative experiences, non-affirmative experiences and clinician relationship. Lack of information and non-affirmative experiences are contributing to poor clinician–patient relationships with transgender populations and impactingattrition. | Modules including information on the transgender community should be included in nursing curricula and supported by nursing management. These modules should support a gender-affirmative approach to the care of transgender populations. Future research should explore the feasibility of including transgender-specific education into the curriculum for training nurses in an Irish context as well as supporting nurse managers in this area. |

| Hughto et al. (2018) USA [30] | To assess the experiences of incarcerated transgendered women receiving physical, mental and transition-related healthcare in correctional settings and to document potential barriers to healthcare. | Transgender women who had been incarcerated in the United States within the past five years (n = 20), aged 22–53 years | Semi-structured individual interviews. Grounded theory. | Participants described an institutional culture in which their feminine identity was not recognized and institutional policies acted as a form of structural stigma that created and reinforced the gender binary and restricted access to healthcare. Some participants saw healthcare barriers as a result of bias, others attributed barriers to providers’ limited knowledge or inexperience caring for transgender patients. Access to physical, mental and gender transition-related healthcare negatively impacted participants’ health while incarcerated. | Findings highlight the need for interventions that target multi-level barriers to care in order to improve incarcerated transgender women’s access to quality, gender affirmative healthcare. |

| Johnson et al. (2020) USA [31] | To describe the spectrum of specific parental behaviours across three categories—rejecting, supportive, and mixed behaviours—and to describe the perceived psychosocial consequences of each of the three categories of parental behaviours on the lives of trans adolescents. | Transgender individuals (n = 24), aged 16–20 years. | Two in-depth interviews with each participant. Use of techniques that incorporated visual images and representations. Thematic Analysis. | Overall, participants reported that rejecting and mixed parental behaviours contributed to a range of psychosocial problems (e.g., depression and suicidal ideation), while supportive behaviours increased positive wellbeing. | These findings expand upon descriptions of parental support and rejection within the trans adolescent literature and can help practitioners target specific behaviours for interventions. |

| Knutson et al. (2018) USA [32] | To explore transgender or gender nonconforming individuals’ health care recommendations for rural settings. | Transgender individuals (n = 10), aged 23–59 years. | Semi-structured individual interviews. Consensual Qualitative Research. | Themes looked at access to care, quality control, difficulties, and mentorship. Understanding the content of interpersonal exchanges in transgender communities may support the creation of more effective health services and community building initiatives. | Additional research is needed to assess dimensions of community building and shared knowledge in rural transgender communities that reach beyond healthcare utilization and access. |

| Lykens et al. (2018) USA [33] | To explore the healthcare experiences of genderqueer or nonbinary young adults. | Genderqueer or non-binary young adults (n = 10), aged 20–23 years. | Semi-structured individual interviews. Emergent coding analysis. | Participants faced unique challenges even at clinics specializing in gender-affirming healthcare. They felt misunderstood by providers who approached them from a binary transgender perspective and consequently often did not receive care sensitive to nonbinary identities. Participants felt that the binary transgender narrative pressured them to conform to binary medical narratives throughout healthcare interactions. | GQ/NB young adults have unique healthcare needs but often do not feel understood by their providers. There is a need for existing healthcare systems to serve GQ/NB young adults more effectively. |

| McCann (2015) Ireland [34] | To elicit the views and opinions of transgender people in relation to mental health concerns. | Transgender individuals (n = 4), aged 28–54 years. | Semi-structured individual interviews. Thematic Analysis. | Participants identified challenges and opportunities for enhancing mental health service provision for transgender people and their families. Some of the highlighted concerns related to practitioner attributes and relevant psychosocial supports. | Practitioners need to be knowledgeable and competent in the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of transgender mental health issues. There needs to be adequate funding for future research and collaborative work between transgender community groups and mental health services. |

| Mizock & Lundquist (2016) USA [35] | To identify the specific issues in the psychotherapy process for transgender or gender non-conforming individuals (TGNC) | Participants who self-identified as TGNC (n = 45), aged 21–71 years. | Semi-structured individual interviews. Constant comparative method. | Psychotherapy missteps were identified as education burdening, gender inflation, gender narrowing, gender avoidance, gender generalizing, gender repairing, gender pathologizing, and gate-keeping. Reliance on the client to educate the psychotherapist about trans issues and concerns. | Further research is recommended to focus on the qualities of successful experiences in psychotherapy among TGNC clients to balance this perspective. |

| Real-Quintanar et al. (2020) Mexico [43] | To explore the medical and mental health needs of transgender men. | Transgender men (n = 4), aged 22–39 years. | Semi-structured individual interviews. Thematic analysis. | Participants developed their trans identity in childhood. Many bullied at school. No helpful contact with health professionals reported. Those that did experienced ‘mistreatment’, being criticised and judged. Participants felt shame and rejection. | Health professionals need training and education of trans issues and concerns. They need knowledge, skills and competence to better meet the distinct needs of trans people. Need to address mental health issues caused by stigma and discrimination. |

| Ritterbusch et al. (2018) Columbia [36] | To examine stigma-related healthcare access and violence experienced by trans women in Columbia. | Transgender women (n = 28), aged 19–56 years. | In-depth individual interviews. Constant comparative method. | Some participants (n = 7) had experienced life-threatening consequences associated with peer-led injection of liquid silicone or other liquids used for body transformation. Many participants (n = 23) reported the informal use of hormone therapy without medical guidance. Some (n = 9) started this practice during early adolescence and 20 people reported ‘losing a peer’ to informal body transformations. Many participants (n = 20) had experienced torture or other grave human rights violations within the Columbian Healthcare System. | HIV prevention programmes should adopt a human rights process rather than ‘disease control.’ Advocacy and trans support programmes should be rights-based, accessible and safe. Need to be clear policies protecting the rights of trans people and that challenges stigma, victimisation and discrimination. Health curricula should be reflective of the distinct needs of this population and practitioners develop the necessary knowledge, skills and attitudes to provide appropriate supports and interventions. |

| Sansfaçon et al. (2018) Canada [37] | To explore the factors that influence transgender youths’ wellbeing in Quebec. | Transgender youth (n = 24), aged 15–25 years. | In-depth individual interviews. Constant comparative method. | Youth with access to specialized, trans-affirmative health centres and mental health professionals reported how welcoming services and providers helped them affirm their identity and feel supported. Accepting and knowledgeable providers are key to helping youth cope with gender identity issues. A supportive and respectful healthcare environment can contribute to their well-being and health. Supportive psychological services can enhance youth’s capacity to face adversity and build resilience. | Health professionals need to be more knowledgeable about trans issues with clear policies supporting interventions to address possible ‘informational’ and ‘institutional’ erasure. Ensure that any information or knowledge is non-pathologising and non-exclusionary of diversity. Need to apply an intersectional lens to trans experiences that goes beyond gender identity issues alone. Question the distinction between recognition and visibility and what these concepts mean for trans people. |

| Santos et al. (2019) USA [38] | To elicit transgender university students’ experiences of accessing primary and mental health services via university health services. | Transgender students (n = 11), aged 18–24 years. | Semi-structured individual interviews. Thematic analysis. | University Health Services (UHS) are not adequately meeting transgender students’ health care needs. Students reported being repeatedly misgendered and addressed by the incorrect name by staff. Some providers asked inappropriate and irrelevant questions about their gender identity during clinical appointments. These and related experiences deterred many participants from returning to the UHS. | Accurate and inclusive transgender students’ identities are systematically included in their medical records as recommended by the Fenway Institute and WPATH. University Health Services staff should be trained in trans-gender-inclusive best practices and trained in trans-specific health care delivery in order to ensure inclusivity. Provide staff skills training focusing on learning and practicing ways to actively demon-strate both trans-awareness and trans-allyship. |

| Strauss et al. (2019) Australia [39] | To explore trans and gender diverse young people’s attitudes towards game-based digital mental health interventions. | Trans and gender diverse youth (n = 14), aged 11–18 years. | Focus group interviews. Thematic analysis. | Games can bolster general well-being. Peer support can improve mental well-being. Apps were reportedly valuable due to the mental health management skills that they teach the individual, such as coping mechanisms (e.g., through mindfulness, grounding and breathing exercises) and promotion of self-care. Trans informative content is important in game-play. Some containing violence or inappropriate content perceived as unhelpful to mental health. | Game-based digital mental health interventions, and their potential utility in TGD populations have utlility. The intervention should involve TGD or LGBT+ consultation in its development and should be marketed to TGD young people through trusted sources, namely mental health professionals or peers. Trans-affirmative, peer-informed and gender inclusive related content is important to game-play. Participants voiced that a positive feature of many games is the ability to play as, and express, their affirmed gender. |

| Taylor (2013) Canada [44] | To examine transmen’s experiences of health and social care. | Transmen (n = 3), aged 21–29 years. | Semi-structured individual interviews. Thematic analysis. | Major themes indicated provider competence as being problematic in the areas of knowledge gathering, quality helping relationships, and access to health interventions. Cultural competency deficient and a lack of research on trans issues to inform practice. Access to supports and interventions problematic. Self-advocacy common among trans men. | Social workers and other health care providers to expand their thinking beyond binary concepts and move to a more “constellational” view of gender identity. Practitioners have an ethical responsibility to address discrimination based on sex or gender identity, challenge diagnoses such as Gender Identity Disorder and break down the gender binary. |

| Vermeir et al. (2018) Canada [40] | To identify the barriers to emergency healthcare for trans adults. | Transgender adults (n = 8), aged 18–44 years. | Semi-structured individual interviews. Constant comparative method. | Trans participants felt discriminated against and socially excluded in primary and emergency care settings. Discrimination ranged from subtle to overt and often have detrimental consequences. Trans people expected to be more active in their care including educating health professionals. | Important to educate health providers about trans identity to enable trans people to feel more included in their care. Trans narratives should be used to inform future developments in health and social care. |

| von Vogelsang et al. (2016) Sweden [41] | To describe transgender people’s experiences of health professionals during sexual reassignment process. | Transgender women (n = 6), aged 20–36 years. | Semi-structured individual interviews. Content analysis. | Encounters with professionals seen as good when being respectful, acted professionally and built trust and confidence. Poor experiences included lack of knowledge, withholding information, abusing power, gender stereotyping and using the wrong name. Felt dependent on health professionals. | Improved education for health professionals on transgender issues. Increased awareness of the impact of negative attitudes, poor skills and lack of knowledge. |

| Yan et al. (2019) China [42] | To explore transgender women’s experiences of identity, stigma and HIV in China. | Transgender women (n = 14), aged 20–55 years. | In-depth individual interviews and focus group interviews. Thematic analysis. | Participants faced discrimination, poor access to services, unmet mental health needs. Social networks remain sparse and hidden. Almost all participants experienced family rejection. Low awareness and testing for HIV. | Need trans-specific services including gender-affirmative medical and mental health care. HIV prevention strategies required. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCann, E.; Donohue, G.; Brown, M. Experiences and Perceptions of Trans and Gender Non-Binary People Regarding Their Psychosocial Support Needs: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073403

McCann E, Donohue G, Brown M. Experiences and Perceptions of Trans and Gender Non-Binary People Regarding Their Psychosocial Support Needs: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research Evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(7):3403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073403

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCann, Edward, Gráinne Donohue, and Michael Brown. 2021. "Experiences and Perceptions of Trans and Gender Non-Binary People Regarding Their Psychosocial Support Needs: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research Evidence" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 7: 3403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073403

APA StyleMcCann, E., Donohue, G., & Brown, M. (2021). Experiences and Perceptions of Trans and Gender Non-Binary People Regarding Their Psychosocial Support Needs: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research Evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073403