Daily Tasks and Willingness to Work of Dental Hygienists in Nursing Facilities Using Japanese Dental Hygienists’ Survey 2019

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

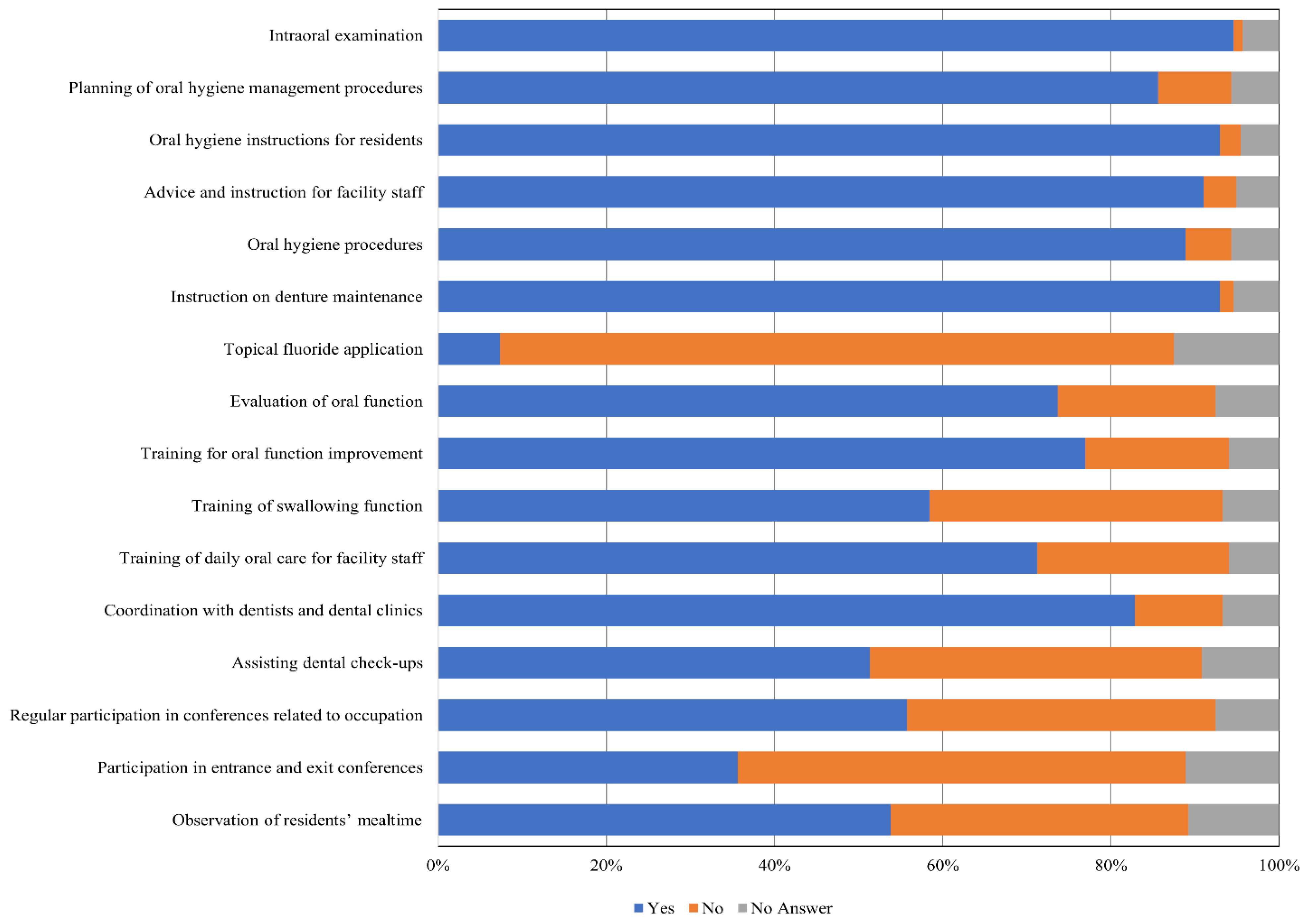

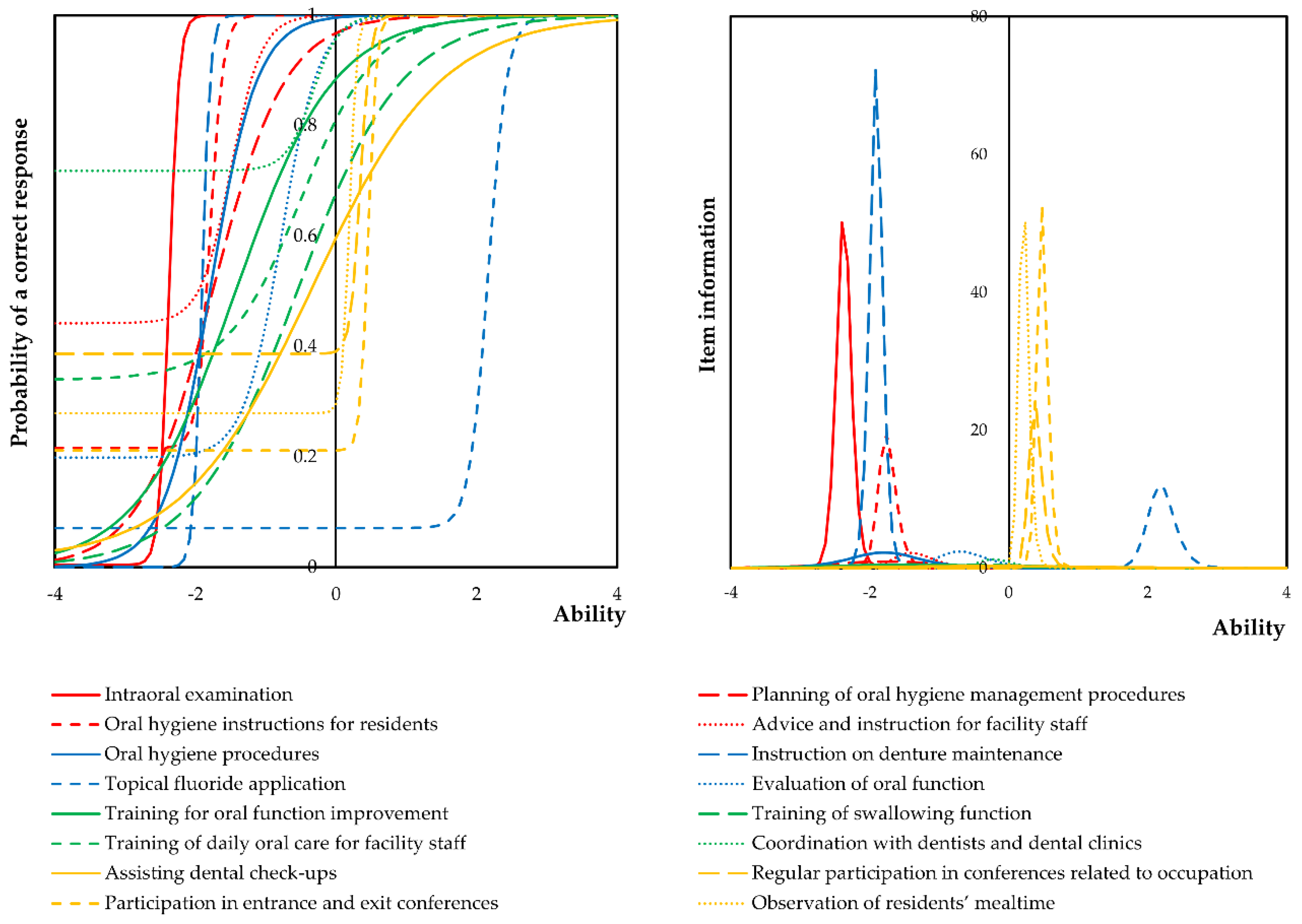

3.2. IRT Analysis of Dental Hygienists’ Daily Tasks at Nursing Facilities

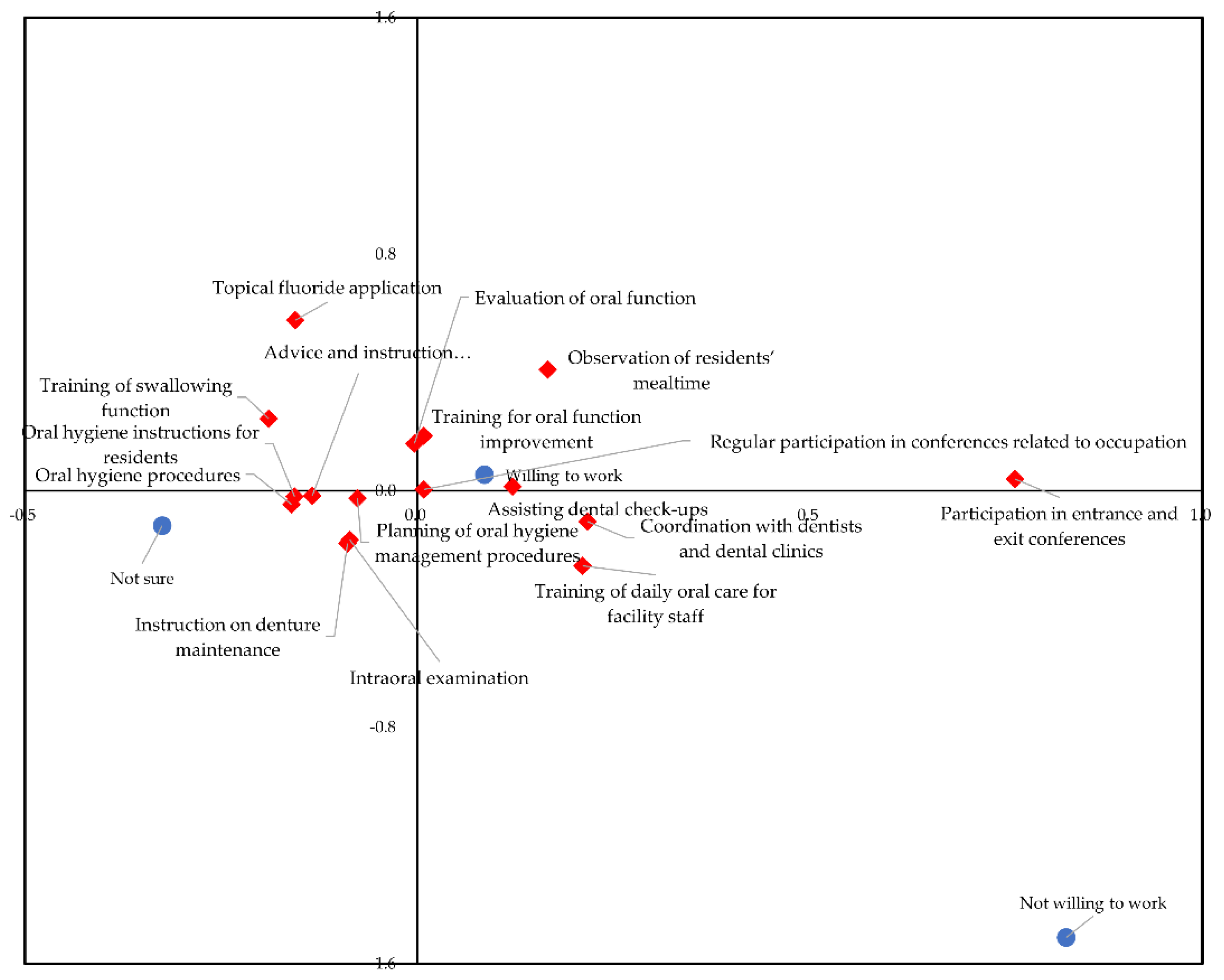

3.3. Correlation between Daily Tasks and a Willingness to Work

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tanaka, T.; Takahashi, K.; Hirano, H.; Kikutani, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Ohara, Y.; Furuya, H.; Tetsuo, T.; Akishita, M.; Iijima, K. Oral frailty as a risk factor for physical frailty and mortality in community-dwelling elderly. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 1661–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, A.; Yoshimura, Y.; Wakabayashi, H.; Tsuji, Y. Poor oral status is associated with rehabilitation outcome in older people. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Okada, K.; Kondo, M.; Matsushita, T.; Nakazawa, S.; Yamazaki, Y. Oral health for achieving longevity. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Ohara, Y.; Edahiro, A.; Sato, E.; Suga, T.; Hirano, H. Factors associated with older adults’ need for oral hygiene management by dental professionals. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2016, 16, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiesi, F.; Grazzini, M.; Innocenti, M.; Giammarco, B.; Simoncini, E.; Garamella, G.; Zanobini, P.; Perra, C.; Baggiani, L.; Lorini, C.; et al. Older people living in nursing facilities: An oral health screening survey in Florence, Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonde, L.; Emami, A.; Kiljunen, H.; Nordenram, G. Care providers’ perceptions of the importance of oral care and its performance within everyday caregiving for nursing home residents with dementia. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2011, 25, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, L.; Seleskog, B.; Wårdh, I.; von Bültzingslöwen, I. Oral care perspectives of professionals in nursing facilities for the elderly. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2013, 11, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleskog, B.; Lindqvist, L.; Wårdh, I.; Engström, A.; von Bültzingslöwen, I. Theoretical and hands-on guidance from dental hygienists promotes good oral health in elderly people living in nursing facilities, a pilot study. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2018, 16, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneyama, T.; Yoshida, M.; Matsui, T.; Sasaki, H. Oral care and pneumonia. Oral Care Working Group. Lancet 1999, 354, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikutani, T.; Enomoto, R.; Tamura, F.; Oyaizu, K.; Suzuki, A.; Inaba, S. Effects of oral functional training for nutritional improvement in Japanese older people requiring long-term care. Gerodontology 2006, 23, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumi, Y.; Ozawa, N.; Miura, H.; Michiwaki, Y.; Umemura, O. Oral care help to maintain nutritional status in frail older people. Arch Gerontol. Geriatr. 2010, 51, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, M.; Kato, T.; Fujii, W.; Ozeki, M.; Yokoyama, M.; Hamajima, N.; Saitoh, E. Effects of dental treatment on the quality of life and activities of daily living in institutionalized elderly in Japan. Arch Gerontol. Geriatr. 2010, 50, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, Y.; Izumi, M.; Nakamichi, A.; Isobe, A.; Akifusa, S. Validity and reliability of the oral health-related caregiver burden index. Gerodontology 2017, 34, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, Y.; Shimoyama, K.; Suzuki, Y. Recognition and behaviour of caregiver managers related to oral care in the community. Gerodontology 2009, 26, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwagami, M.; Tamiya, N. The long-term care insurance system in Japan: Past, present, and future. JMA J. 2019, 2, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kishimoto, N.; Stegaroiu, R.; Shibata, S.; Otsuka, H.; Ohuchi, A. Income from nutrition and oral health management among long-term care insurance facilities in Niigata Prefecture, Japan. Gerodontology 2019, 36, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Dental Hygienists’ Association. The Dental Hygienist Profession in Japan. Available online: https://www.jdha.or.jp/en/ (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Nomura, Y.; Kakuta, E.; Okada, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Tomonari, H.; Hosoya, N.; Hanada, N.; Yoshida, N.; Takei, N. Prioritization of the skills to be mastered for the daily jobs of Japanese dental hygienists. Int. J. Dent. 2020, 2020, 4297646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Ohara, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Okada, A.; Hosoya, N.; Hanada, N.; Takei, N. Dental hygienists’ practice in perioperative oral care management according to the Japanese dental hygienists survey 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohara, Y.; Nomura, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Okada, A.; Hosoya, N.; Hanada, N.; Hirano, H.; Takei, N. Job attractiveness and job satisfaction of dental hygienists: From the Japanese dental hygienists’ survey 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Okada, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kakuta, E.; Tomonari, H.; Hosoya, N.; Hanada, N.; Yoshida, N.; Takei, N. Behind leaving the job and rejoining it by the Japanese dental hygienist. Open Dent. J. 2020, 14, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Okada, A.; Kakuta, E.; Otsuka, R.; Saito, H.; Maekawa, H.; Daikoku, H.; Hanada, N.; Sato, T. Workforce and contents of home dental care in the Japanese insurance system. Int. J. Dent. 2020, 2020, 7316796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Okada, A.; Miyoshi, J.; Mukaida, M.; Akasaka, E.; Saigo, K.; Daikoku, H.; Maekawa, H.; Sato, T.; Hanada, N. Willingness to work and the working environment of Japanese dental hygienists. Int. J. Dent. 2018, 2018, 2727193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Otsuka, R.; Wint, W.Y.; Okada, A.; Hasegawa, R.; Hanada, N. Tooth-level analysis of dental caries in primary dentition in Myanmar children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. Survey of Dental Hygienists and Dental Technicians. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/eisei/18/dl/kekka2.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. Situations Surrounding the Field of Nursing Care. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12300000/000608284.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Sjögren, P.; Kullberg, E.; Hoogstraate, J.; Johansson, O.; Herbst, B.; Forsell, M. Evaluation of dental hygiene education for nursing home staff. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wårdh, I.; Jonsson, M.; Wikström, M. Attitudes to and knowledge about oral health care among nursing home personnel--an area in need of improvement. Gerodontology 2012, 29, e787–e792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Available online: https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/ (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Ino, Y.; Shimauchi, A.; Tachi, T.; Noguchi, Y.; Sakai, C.; Iguchi, K.; Kano, A.; Teramachi, H. Community pharmacy-level factors associated with medical and nursing home facility collaboration in Japan. Pharmazie 2019, 74, 630–638. [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, S.; Fujita, J.; Ikezaki, S.; Nakatani, E.; Tsujimura, M. Effect of a multidisciplinary end-of-life educational intervention on health and social care professionals: A cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcon, C.I.; Coplen, A.E.; Davis-Risen, S.; Korte, D.; Fontana, M.; Furgeson, D. Impact of an interprofessional education intervention and collaborative practice agreements of expanded practice dental hygienists in Oregon. J. Dent. Hyg. 2020, 94, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swanson Jaecks, K.M. Current perceptions of the role of dental hygienists in interdisciplinary collaboration. J. Dent. Hyg. 2009, 83, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.C.; Kanji, Z. Exploring interprofessional relationships between dental hygienists and health professionals in rural Canadian communities. J. Dent. Hyg. 2017, 9, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Luebbers, J.; Gurenlian, J.; Freudenthal, J. Physicians’ perceptions of the role of the dental hygienist in interprofessional collaboration: A pilot study. J. Interprof. Care 2021, 35, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovden, E.S.; Ansteinsson, V.E.; Klepaker, I.V.; Widström, E.; Skudutyte-Rysstad, R. Dental care for drug users in Norway: Dental professionals’ attitudes to treatment and experiences with interprofessional collaboration. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shacham, M.; Hamama-Raz, Y.; Kolerman, R.; Mijiritsky, O.; Ben-Ezra, M.; Mijiritsky, E. COVID-19 factors and psychological factors associated with elevated psychological distress among dentists and dental hygienists in Israel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 22, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ohara, Y.; Nomura, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Okada, A.; Hosoya, N.; Hanada, N.; Hirano, H.; Takei, N. Daily Tasks and Willingness to Work of Dental Hygienists in Nursing Facilities Using Japanese Dental Hygienists’ Survey 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3152. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063152

Ohara Y, Nomura Y, Yamamoto Y, Okada A, Hosoya N, Hanada N, Hirano H, Takei N. Daily Tasks and Willingness to Work of Dental Hygienists in Nursing Facilities Using Japanese Dental Hygienists’ Survey 2019. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):3152. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063152

Chicago/Turabian StyleOhara, Yuki, Yoshiaki Nomura, Yuko Yamamoto, Ayako Okada, Noriyasu Hosoya, Nobuhiro Hanada, Hirohiko Hirano, and Noriko Takei. 2021. "Daily Tasks and Willingness to Work of Dental Hygienists in Nursing Facilities Using Japanese Dental Hygienists’ Survey 2019" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 6: 3152. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063152

APA StyleOhara, Y., Nomura, Y., Yamamoto, Y., Okada, A., Hosoya, N., Hanada, N., Hirano, H., & Takei, N. (2021). Daily Tasks and Willingness to Work of Dental Hygienists in Nursing Facilities Using Japanese Dental Hygienists’ Survey 2019. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3152. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063152