Challenges to the Fight against Rabies—The Landscape of Policy and Prevention Strategies in Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Global Efforts for Rabies Prevention, Control, and Elimination

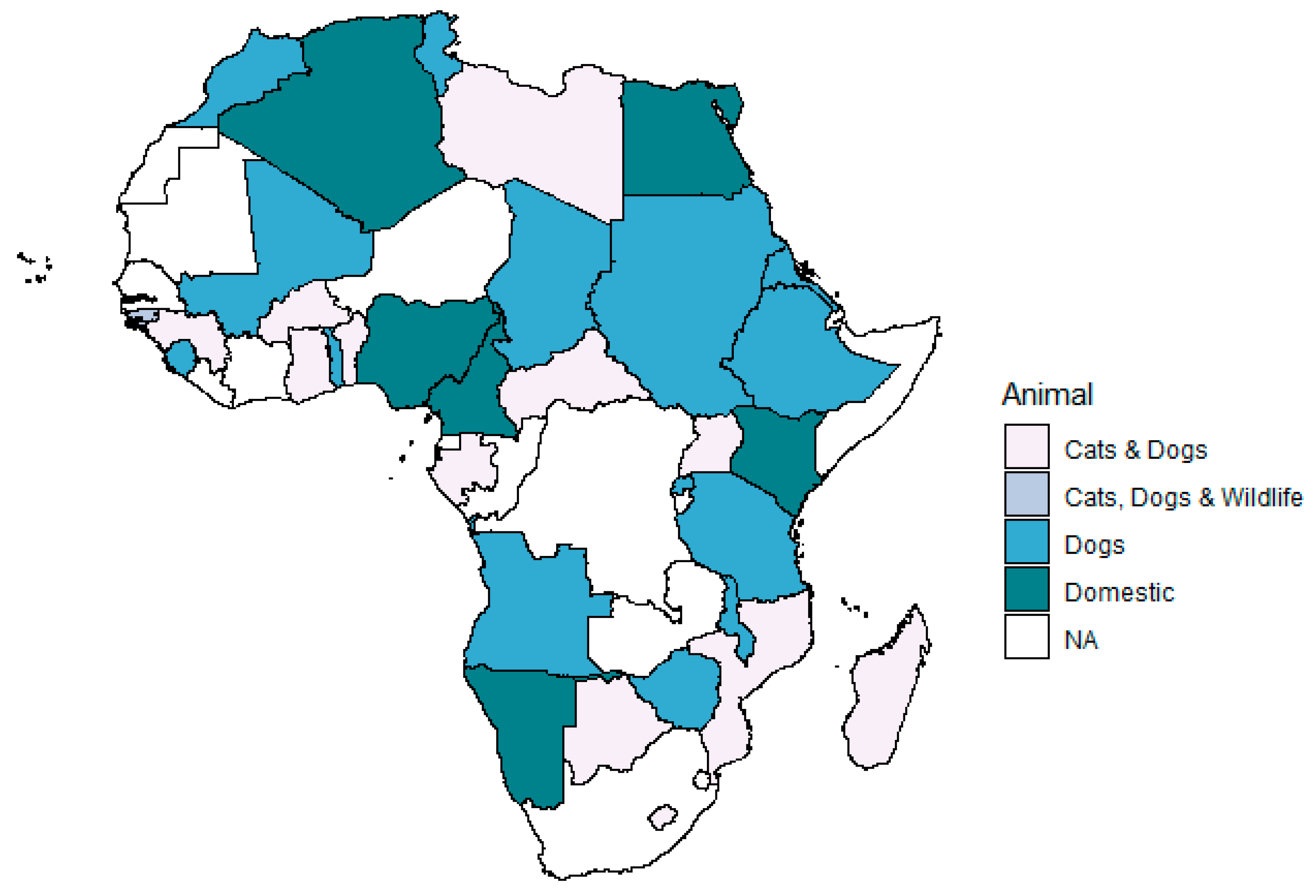

2.2. Vaccination Programs in African Countries

2.3. National Rabies Prevention and Control Plans

2.4. Challenges Identified in National Plans

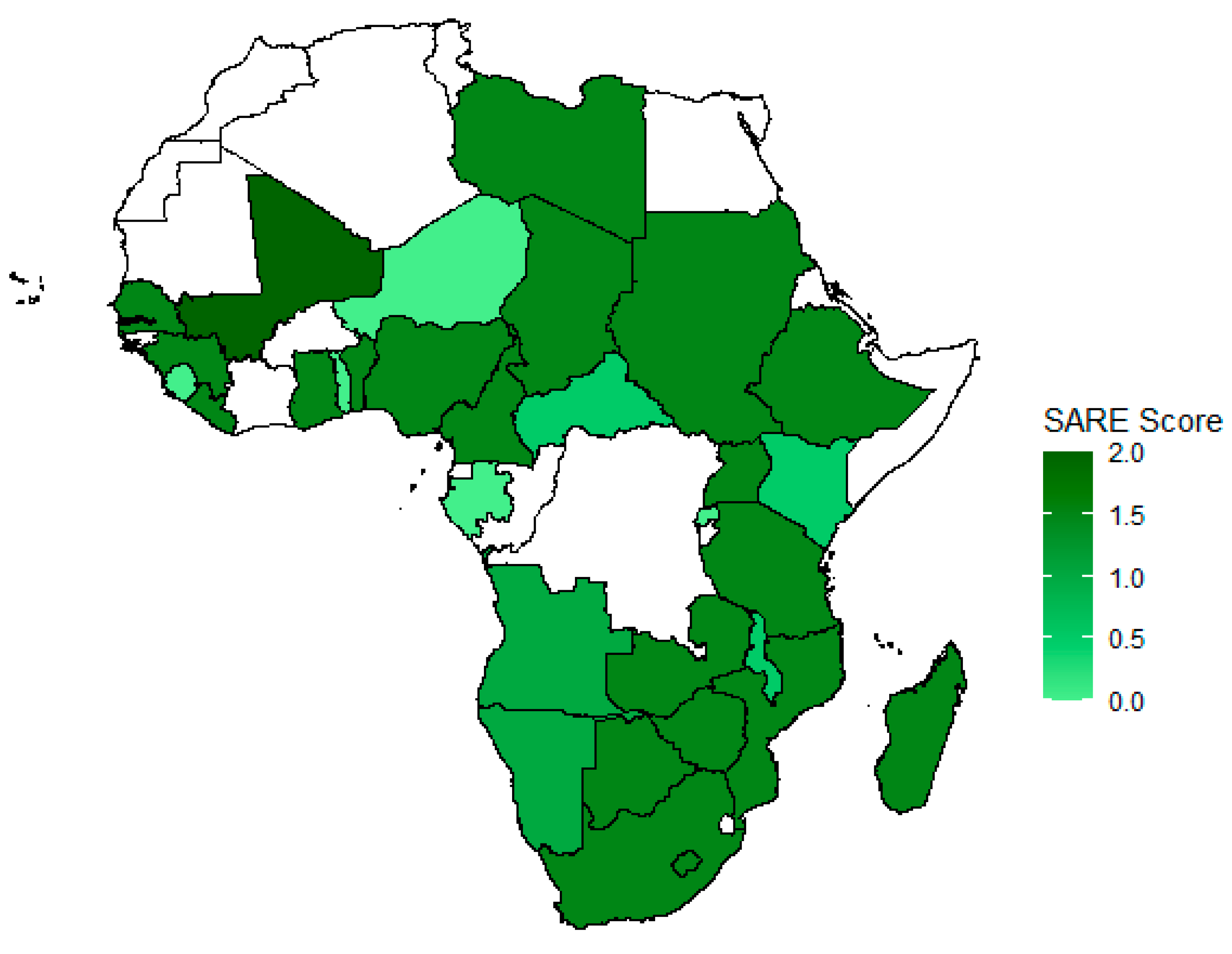

2.5. Monitoring Progress in Rabies Prevention, Control, and Elimination

2.6. Future Perspectives in Rabies Prevention, Control, and Elimination

3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abela-Ridder, B. Rabies: 100 per cent fatal, 100 per cent preventable. Vet. Rec. 2015, 177, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampson, K.; Coudeville, L.; Lembo, T.; Sambo, M.; Kieffer, A.; Attlan, M.; Barrat, J.; Blanton, J.D.; Briggs, D.J.; Cleaveland, S.; et al. Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies, Third Report; WHO Technical Report Series, No. 1012; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fooks, A.R.; Banyard, A.C.; Horton, D.L.; Johnson, N.; McElhinney, L.M.; Jackson, A.C. Current status of rabies and prospects for elimination. Lancet 2014, 384, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.; Shwiff, S.A. The Cost of Canine Rabies on Four Continents. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2015, 62, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Division for Sustainable Development Goals: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rattanavipapong, W.; Thavorncharoensap, M.; Youngkong, S.; Genuino, A.J.; Anothaisintawee, T.; Chaikledkaew, U.; Meeyai, A. The impact of transmission dynamics of rabies control: Systematic review. Vaccine 2019, 37 (Suppl. 1), A154–A165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anothaisintawee, T.; Julienne Genuino, A.; Thavorncharoensap, M.; Youngkong, S.; Rattanavipapong, W.; Meeyai, A.; Chaikledkaew, U. Cost-effectiveness modelling studies of all preventive measures against rabies: A systematic review. Vaccine 2019, 37 (Suppl. 1), A146–A153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, K.; Ventura, F.; Steenson, R.; Mancy, R.; Trotter, C.; Cooper, L.; Abela-Ridder, B.; Knopf, L.; Ringenier, M.; Tenzin, T.; et al. The potential effect of improved provision of rabies post-exposure prophylaxis in Gavi-eligible countries: A modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.E.; Salahuddin, N. Current status of human rabies prevention: Remaining barriers to global biologics accessibility and disease elimination. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2019, 18, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinson, A.; Bennett, M.; Brennan, M.L.; Dean, R.S.; Stavisky, J. Evaluating the role of surgical sterilisation in canine rabies control: A systematic review of impact and outcomes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.R. Importance of a One Health approach in advancing global health security and the Sustainable Development Goals. Rev. Sci. Tech. Int. Off. Epizoot. 2019, 38, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, T.P.; Coetzer, A.; de Balogh, K.; Wright, N.; Nel, L.H. The Pan-African Rabies Control Network (PARACON): A unified approach to eliminating canine rabies in Africa. Antivir. Res. 2015, 124, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, G.; Fuller, D.Q. The Evolution of Animal Domestication. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2014, 45, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavan, R.P.; King, A.I.M.; Sutton, D.J.; Tunceli, K. Rationale and support for a One Health program for canine vaccination as the most cost-effective means of controlling zoonotic rabies in endemic settings. Vaccine 2017, 35, 1668–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Developing a stepwise approach for rabies prevention and control. In FAO Animal Production and Health Proceedings, Proceedings of the FAO/GARC Workshop, Rome, Italy, 6–8 November 2012; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nel, L.H. The role of non-governmental organisations in controlling rabies: The Global Alliance for Rabies Control, Partners for Rabies Prevention and the Blueprint for Rabies Prevention and Control. Rev. Sci. Tech. Int. Off. Epizoot. 2018, 37, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lembo, T.; Partners for Rabies Prevention. The Blueprint for Rabies Prevention and Control: A Novel Operational Toolkit for Rabies Elimination. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahiaoui, F.; Kardjadj, M.; Laidoudi, Y.; Medkour, H.; Ben-Mahdi, M.H. The epidemiology of dog rabies in Algeria: Retrospective national study of dog rabies cases, determination of vaccination coverage and immune response evaluation of three commercial used vaccines. Prev. Vet. Med. 2018, 158, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardjadj, M.; Ben-Mahdi, M.H. Epidemiology of dog-mediated zoonotic diseases in Algeria: A One Health control approach. New Microbes New Infect. 2019, 28, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health Eritrea. National Master Plan for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2015–2020; Ministry of Health Eritrea: Asmara, Eritrea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Health Services—Public Health Division. Master Plan for Neglected Tropical Diseases Programme, Ghana (2016–2020); Public Health Division: Accra, Ghana, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Republic of Liberia—Ministry of Health. Master Plan for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2016–2020; Ministry of Health: Monrovia, Liberia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Mali Ministere du Sante. Mali Plan Directeur de Lutte Contre les Maladies Tropicales Négligées (M.T.N.) 2017–2021; Republic of Mali Ministere du Sante: Bamako, Mali, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Republique du Niger Ministere de la Sante Publique. Plan Directeur de Lutte Contre les Maladies Tropicales Negligees Niger 2016–2020; Republique du Niger Ministere de la Sante Publique: Niamey, Niger, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Nigeria—Ministry of Health. Neglected Tropical Diseases Nigeria Multi—Year Master Plan 2015–2020; Ministry of Health: Abuja, Nigeria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. South Sudan National Master Plan for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2016–2020; Ministry of Health: Juba, South Sudan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tricou, V.; Bouscaillou, J.; Kamba Mebourou, E.; Koyanongo, F.D.; Nakouné, E.; Kazanji, M. Surveillance of Canine Rabies in the Central African Republic: Impact on Human Health and Molecular Epidemiology. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republique Democratique du Congo—Ministere de la Sante Publique. Plan Strategique de Lutte Contre les Maladies Tropicales Negligees a Chimiotherapie Preventive 2016–2020; Ministere de la Sante Publique: Kinshasa, Congo, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and the Social Welfare, Republic of the Gambia. National Master Plan for Neglected Tropical Diseases 2015–2020; Ministry of Health and the Social Welfare: Banjul, Gambia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Direccao Geral da Saude Publica, Republica da Guine-Bissau MdSP. Plan Directeur de Lutte Contre les Maladies Tropicales Negligees en Guinee Bissau (2014–2020); Direccao Geral da Saude Publica: Bissau, Guine-Bissau, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Republique du Senegal—Ministere de la Sante et de l’action Sociale. Plan Stratégique de Lutte Contre les Maladies Tropicales Négligées 2016–2020; Ministere de la Sante et de l’action Sociale: Dakar, Senegal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Kenya—Ministry of Health and Ministry of Agriculture Livestock and Fisheries Zoonotic Disease Unit. Strategic Plan for the Elimination of Human Rabies in Kenya 2014–2030; Ministry of Health and Ministry of Agriculture Livestock and Fisheries Zoonotic Disease Unit: Nairobi, Kenya, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. The 2nd Kenya National Strategic Plan Forcontrol of Neglected Tropical Diseases 2016–2020, Revised ed.; Ministry of Health: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Kingdom of Swaziland. Masterplan towards the Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases 2015–2020; Ministry of Health: Mbabane, Eswatini, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Royame du Maroc Ministere de la Sante. Programme National de Lutte Contre la Rage; Royame du Maroc Ministere de la Sante: Rabat, Morocco, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Republique Tunisienne Minstere de la Sante. La Commision National de Lutte Contre la Rage—Programme National de la Lutte Contre la Rage; Republique Tunisienne Minstere de la Sante: Bab saadoun, Tunis, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mpolya, E.A.; Lembo, T.; Lushasi, K.; Mancy, R.; Mbunda, E.M.; Makungu, S.; Maziku, M.; Sikana, L.; Jaswant, G.; Townsend, S.; et al. Toward Elimination of Dog-Mediated Human Rabies: Experiences from Implementing a Large-scale Demonstration Project in Southern Tanzania. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assenga, J.A.; Markalio, G.P. Review of National Rabies Control Efforts: Tanzania. 2017. Available online: https://rabiesalliance.org/sites/default/files/resources/2017-06/Tanzania%20Country%20report.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2019).

- Ntampaka, P.; Nyaga, P.N.; Niragire, F.; Gathumbi, J.K.; Tukei, M. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding rabies and its control among dog owners in Kigali city, Rwanda. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntegeyibizaza, S. 1st Meeting of Directors of Rabies Control Progroams in East Africa, Rwanda Presentation. Available online: https://rabiesalliance.org/sites/default/files/resources/2017-06/Rwanda%20Country%20report.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Republic of Uganda. Uganda One Health Strategic Plan 2018–2022; Ministry of Health: Kampala, Uganda, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Parodi, P.; Telma, D.; Daniel, S.; Di Giuseppe, P.; del Negro, E.; Scacchia, M. Rabies in Angola: A One health Approach. In Proceedings of the One Health for the Real World: Zoonoses, Ecosystems and Wellbeing, London, UK, 17–18 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Unknown. Rabies Stakeholder Meeting, 2018 West Africa. Available online: https://rabiesalliance.org/resource/elma-zanamwerabies-stakeholder-meetings-faoparacon-2018 (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Mutorwa, J. Official and Public Launch of the Directorate of Veterinary Services’ Rabies Control Strategy; Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry: Windhoek, Namibia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bobo, G. Efforts to Eliminate dog-mediated Human Rabies Intensifies; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Republica de Guinea Ecuatorial. Guinea Ecuatorial—Plan Directeur de Lutte Contre les Maladies Tropicales Négligées (MTN) 2018–2022; Ministere de la Santé et Bien Être Social: Malabo, Equatorial Guinea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Malawi. Malawi NTD Master Plan 2015–2020; Ministry of Health Malawi: Lilongwe, Malawi, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Seychelles. Seychelles Neglected Tropical Diseases Master Plan 2015–2020; Ministry of Health Seychelles: Victoria, Seychelles, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzer, A.; Coertse, J.; Makalo, M.J.; Molomo, M.; Markotter, W.; Nel, L.H. Epidemiology of Rabies in Lesotho: The Importance of Routine Surveillance and Virus Characterization. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2017, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coetzer, A.; Kidane, A.H.; Bekele, M.; Hundera, A.D.; Pieracci, E.G.; Shiferaw, M.L.; Wallace, R.; Nel, L.H. The SARE tool for rabies control: Current experience in Ethiopia. Antivir. Res. 2016, 135, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Organisation for Animal Health. Zero by 30: The Global Strategic Plan to End Human Deaths from Dog-Mediated Rabies by 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weyer, J.; Dermaux-Msimang, V.; Grobbelaar, A.; le Roux, C.; Moolla, N.; Paweska, J.; Blumberg, L. Epidemiology of Human Rabies in South Africa, 2008–2018. S. Afr. Med. J. 2020, 110, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country | Part of Rabies Network | National Rabies Plan (Yes/No) | NTD Master Plan (Yes/No, Time Period) | Rabies Addressed in NTD Master Plan (Yes/No) | Disease Notification (Domestic/Wild/Species Specified) | Precaution at Borders (Domestic/Wild/Species Specified) | Monitoring | Screening | General Surveillance | Targeted Surveillance | Official Vaccination | SARE Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | MEEREB | yes | † | † | D | W/D | D | † | † | † | cattle, dogs, cats | † |

| Angola | PARACON | yes | † | † | W/D | D | W/D | † | W/D | D | dogs | 1 |

| Benin | PARACON | † | † | † | W/D | D | D | † | D | † | cats, dogs | 1.5 |

| Botswana | PARACON | † | Yes (2015–2020) | no | W/D | dogs, cats, sheep | W, cattle | † | cats, dogs, cattle, goats, sheep/W | W | cats, dogs | 1.5 |

| Burkina Faso | PARACON, no data shared | † | † | † | D | cats, dogs | † | † | † | † | cats, dogs | † |

| Burundi | PARACON, no data shared | † | † | † | † | † | † | cattle, cats, dogs | cattle, cats, dogs | † | † | † |

| Cabo Verde | † | † | † | † | D | D | † | † | † | † | † | † |

| Cameroon | PARACON | † | † | † | D | † | † | † | † | dogs | D | 1.5 |

| Central African Republic | PARACON | † | † | † | D | D | † | cats, dogs | cats, dogs | † | cats, dogs | 0.5 |

| Chad | PARACON | † | † | † | dogs | dogs, cats, sheep | dogs | dogs | † | † | dogs | 1.5 |

| Comoros | † | † | † | † | dogs | † | † | † | dogs | † | † | † |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | PARACON | † | Yes (2016–2020) | yes | cats, dogs | † | cats, dogs | cats, dogs | cats, dogs | † | D | 1.5 |

| Djibouti | PARACON, no permission to share data | † | † | † | cattle, cats, dogs | cattle, cats, dogs | † | † | † | † | † | † |

| Egypt | † | † | † | † | W/D | W/D | † | † | † | W/D | D | † |

| Equatorial Guinea | PARACON, no data shared | † | Yes (2018–2022) | yes | D | D | † | † | † | † | † | † |

| Eritrea | PARACON, no data shared | † | Yes (2015–2020) | yes | dogs, cattle, equidae | † | † | † | dogs, cattle, equidae | † | dogs | † |

| Eswatini (Swaziland) | † | † | Yes (2015–2020) | yes | W/D | W, cats, dogs | † | † | W/D | † | dogs | † |

| Ethiopia | † | † | Yes (2016–2020) | no | D | cats, dogs | † | † | D | † | dogs | 1.5 |

| Gabon | PARACON, no permission to share data | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | cats, dogs | 0 |

| Gambia | † | † | Yes (2015–2020) | yes | † | † | † | † | † | † | D | † |

| Ghana | PARACON | † | Yes (2016–2020) | yes | D | † | D | † | D | † | cats, dogs | 1.5 |

| Guinea | PARACON, no permission to share data | † | † | † | D | D | † | † | D | † | cats, dogs | 1.5 |

| Guinea-Bissau | PARACON | † | Yes (2014–2020) | yes | cats, dogs | cats, dogs | cats, dogs | † | cats, dogs | dogs | cats, dogs, W | † |

| Ivory Coast | PARACON | yes | Yes (2016–2020) | no | D | D | † | † | D | † | cats, dogs | 2 |

| Kenya | PARACON | yes | Yes (2016–2020) | no | D | D | D | † | W/D | † | equidae, cattle, sheep, swine, dogs | 0.5 |

| Lesotho | PARACON | † | † | † | D | cats, dogs | † | † | D | † | cats, dogs | 1.5 |

| Liberia | PARACON | † | Yes (2016–2020) | yes | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | 1.5 |

| Libya | MEEREB, PARACON | † | † | † | D | D | † | † | † | † | cats, dogs | 1.5 |

| Madagascar | PARACON | † | † | † | D | D | † | † | D | † | cats, dogs | 1.5 |

| Malawi | PARACON | † | Yes (2015–2020) | yes | W/D | † | † | dogs | W/D | † | dogs | 0.5 |

| Mali | PARACON | † | Yes (2017–2021) | yes | dogs | dogs | † | † | † | † | dogs | 2 |

| Mauritania | PARACON, no data shared | † | † | † | D | † | D | † | D | † | † | † |

| Mauritius | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | |

| Morocco | MEEREB | yes | yes (†) | † | D | cats, dogs | D | † | D | D | dogs | † |

| Mozambique | PARACON | † | † | † | D | D | D | † | D | D | cats, dogs | 1.5 |

| Namibia | PARAVON, no permission to share data | yes | Yes (2015–2020) | no | D | D | D | † | D | † | cattle, dogs, cats | 1 |

| Niger | PARACON | † | Yes (2016–2020) | yes | D | † | † | † | D | † | † | 0 |

| Nigeria | PARACON | † | Yes (2015–2020) | yes | cattle, cats, dogs | † | † | † | cattle, cats, dogs | † | buffalos (D) | 1.5 |

| Republic of the Congo | PARACON no permission to share data | † | † | † | W/D | W/D | W/D | † | W/D | W/D | cats, dogs, equidae | 1 |

| Rwanda | PARACON | † | † | † | D | D | D | D | † | D | dogs | 0 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | † | cattle, dogs, cats, hares, rabbits, sheep, goats, swine | † | † | † |

| Senegal | PARACON | † | Yes (2016–2020) | yes | cattle, cats, dogs | cattle, cats, dogs | cattle, cats, dogs | † | cattle, cats, dogs | † | † | 1.5 |

| Seychelles | † | † | † | † | D | D | † | † | D | † | † | † |

| Sierra Leone | PARACON | yes (not accessible) | † | † | dogs | † | † | † | dogs | † | dogs | 0 |

| Somalia | PARACON, no permission to share data | † | † | † | D | D | D | D | † | † | † | † |

| South Africa | PARACON | † | † | † | W/D | W/D | † | † | W/D | † | † | 1.5 |

| South Sudan | † | † | Yes (2016–2020) | yes | D | D | † | † | † | † | dogs | † |

| Sudan | PARACON | † | † | † | D | † | † | † | † | † | dogs | 1.5 |

| Tanzania | PARACON | † | † | † | D | † | W | † | D | W | dogs | 1.5 |

| Togo | PARACON, no permission to share data | † | † | † | dogs | dogs | dogs | dogs | dogs | dogs | dogs | 0 |

| Tunisia | MEEREB | † | † | † | W/D | W/D | † | † | W/D | † | dogs | † |

| Uganda | PARACON | yes (not accessible) | † | † | D | D | † | † | D | † | cats, dogs | 1.5 |

| Zambia | PARACON, no permission to share data | † | † | † | W/D | cats, dogs | † | † | W/D | † | † | 1.5 |

| Zimbabwe | † | † | † | † | cattle, dogs, goats, cats, swine | cats, dogs | † | † | cattle, goats, cats, swine | † | dogs | 1.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haselbeck, A.H.; Rietmann, S.; Tadesse, B.T.; Kling, K.; Kaschubat-Dieudonné, M.E.; Marks, F.; Wetzker, W.; Thöne-Reineke, C. Challenges to the Fight against Rabies—The Landscape of Policy and Prevention Strategies in Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041736

Haselbeck AH, Rietmann S, Tadesse BT, Kling K, Kaschubat-Dieudonné ME, Marks F, Wetzker W, Thöne-Reineke C. Challenges to the Fight against Rabies—The Landscape of Policy and Prevention Strategies in Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(4):1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041736

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaselbeck, Andrea Haekyung, Sylvie Rietmann, Birkneh Tilahun Tadesse, Kerstin Kling, Maria Elena Kaschubat-Dieudonné, Florian Marks, Wibke Wetzker, and Christa Thöne-Reineke. 2021. "Challenges to the Fight against Rabies—The Landscape of Policy and Prevention Strategies in Africa" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 4: 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041736

APA StyleHaselbeck, A. H., Rietmann, S., Tadesse, B. T., Kling, K., Kaschubat-Dieudonné, M. E., Marks, F., Wetzker, W., & Thöne-Reineke, C. (2021). Challenges to the Fight against Rabies—The Landscape of Policy and Prevention Strategies in Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1736. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041736