Predictive Factors of Self-Reported Quality of Life in Acquired Brain Injury: One-Year Follow-Up

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. CAVIDACE Scale

2.2.2. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9)

2.2.3. Patient Competency Rating Scale (PCRS)

2.2.4. Community Integration Questionnaire (CIQ)

2.2.5. Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)

2.2.6. Social Support Questionnaire-6 (SSQ6)

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Sample

3.2. Changes in QoL from Baseline to One-Year Follow-Up

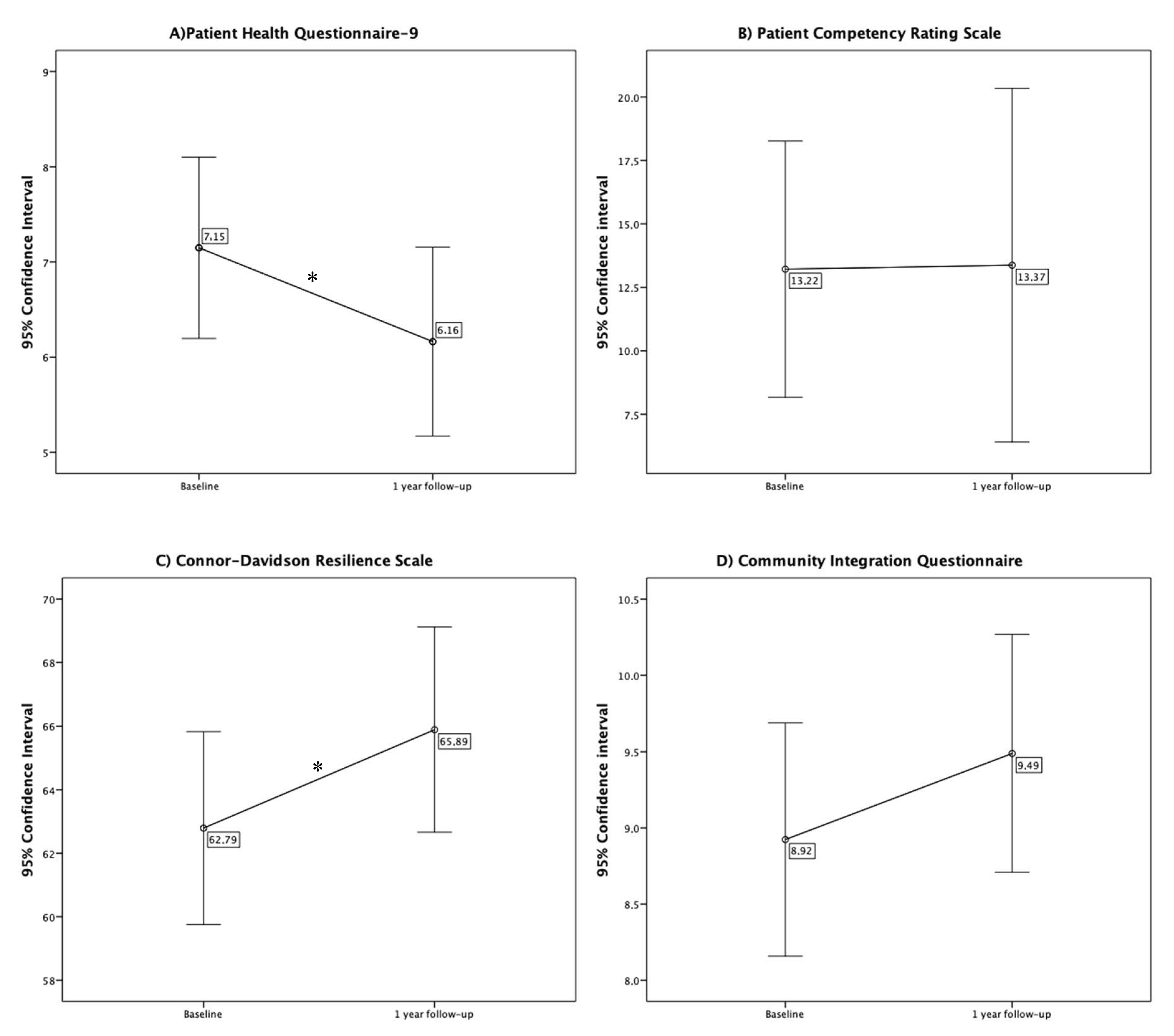

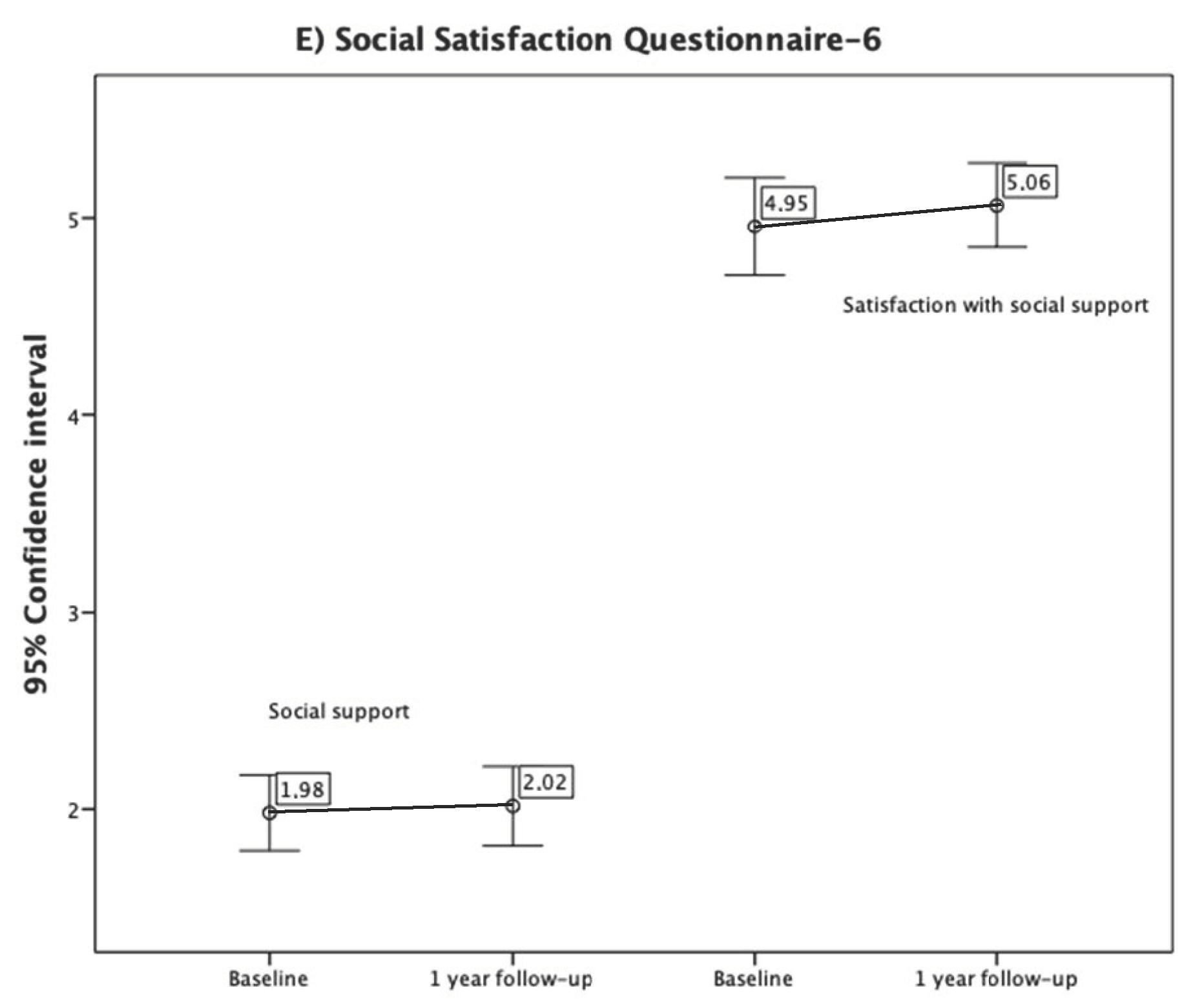

3.3. Changes in Other Variables from the Baseline to One-Year Follow-Up

3.4. Factors Related to QoL: Independent t-Tests and ANOVAs

3.5. Predictors of QoL at One-Year: Regressions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Quezada, M.Y.; Huete, A.; Bascones, L.M. Las Personas Con Daño Cerebral Adquirido En España; FEDACE y Ministerio de Salud, Seguridad Social e Igualdad: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol, A.D.; Higgins, A.M.; Gabbe, B.J.; Murray, L.J.; Cooper, D.J.; Cameron, P.A. Measuring Functional and Quality of Life Outcomes Following Major Head Injury: Common Scales and Checklists. Injury 2011, 42, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberg, H.L.; Røe, C.; Anke, A.; Arango-Lasprilla, J.C.; Skandsen, T.; Sveen, U.; Von Steinbüchel, N.; Andelic, N. Health-Related Quality of Life 12 Months after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Prospective Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 45, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andelic, N.; Howe, E.I.; Hellstrøm, T.; Fernández, M.; Lu, J.; Løvstad, M.; Røe, C. Disability and Quality of Life 20 Years after Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Behav. 2018, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azouvi, P.; Ghout, I.; Bayen, E.; Darnoux, E.; Azerad, S.; Ruet, A.; Vallat-Azouvi, C.; Pradat-Diehl, P.; Aegerter, P.; Charanton, J.; et al. Disability and Health-Related Quality-of-Life 4 Years after a Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Structural Equation Modelling Analysis. Brain Inj. 2016, 30, 1665–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.C.; Guo, S.E.; Huang, K.C.; Lee, B.O.; Fan, J.Y. Trajectories and Associated Factors of Quality of Life, Global Outcome, and Post-Concussion Symptoms in the First Year Following Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 2009–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauwmeijer, E.; Heijenbrok-Kal, M.H.; Peppel, L.D.; Hartjes, C.J.; Haitsma, I.K.; De Koning, I.; Ribbers, G.M. Cognition, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Depression Ten Years after Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 1543–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.R.; Chiu, W.T.; Chen, Y.J.; Yu, W.Y.; Huang, S.J.; Tsai, M.D. Longitudinal Changes in the Health-Related Quality of Life during the First Year after Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andelic, N.; Hammergren, N.; Bautz-Holter, E.; Sveen, U.; Brunborg, C.; Røe, C. Functional Outcome and Health-Related Quality of Life 10 Years after Moderate-to-Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2009, 120, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forslund, M.V.; Roe, C.; Sigurdardottir, S.; Andelic, N. Predicting Health-Related Quality of Life 2 Years after Moderate-to-Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2013, 128, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsson, L.J.; Westerberg, M.; Lexell, J. Health-Related Quality-of-Life and Life Satisfaction 615 Years after Traumatic Brain Injuries in Northern Sweden. Brain Inj. 2010, 24, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M.; Xia, G. Health-Related Quality of Life after Stroke: A 2-Year Prospective Cohort Study in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Neurosci. 2013, 123, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalock, R.L.; Verdugo, M.A. A Conceptual and Measurement Framework to Guide Policy Development and Systems Change. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2012, 9, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalock, R.L. Six Ideas That Are Changing the IDD Field Internationally. Siglo Cero 2018, 49, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalock, R.L.; Verdugo, M.A.; Gomez, L.E.; Reinders, H.S. Moving Us toward a Theory of Individual Quality of Life. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 121, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalock, R.L.; Baker, A.; Claes, C.; Gonzalez, J.; Malatest, R.; van Loon, J.; Verdugo, M.A.; Wesley, G. The Use of Quality of Life Scores for Monitoring and Reporting, Quality Improvement, and Research. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 15, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuelson, I.; Andersson Holmkvist, E.; Björklund, R.; Stålhammar, D. Quality of Life and Post-Concussion Symptoms in Adults after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Population-Based Study in Western Sweden. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2003, 108, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, A.J.; Singh, R.; Victorson, D.; Miskovic, A.; Lai, J.S.; Harvey, R.L.; Cella, D.; Heinemann, A.W. Agreement between Responses from Community-Dwelling Persons with Stroke and Their Proxies on the NIH Neurological Quality of Life (Neuro-QoL) Short Forms. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 1986–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivona, U.; Costa, A.; Contrada, M.; Silvestro, D.; Azicnuda, E.; Aloisi, M.; Catania, G.; Ciurli, P.; Guariglia, C.; Caltagirone, C.; et al. Depression, Apathy and Impaired Self-Awareness Following Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Preliminary Investigation. Brain Inj. 2019, 33, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formisano, R.; Longo, E.; Azicnuda, E.; Silvestro, D.; D’Ippolito, M.; Truelle, J.L.; von Steinbüchel, N.; von Wild, K.; Wilson, L.; Rigon, J.; et al. Quality of Life in Persons after Traumatic Brain Injury as Self-Perceived and as Perceived by the Caregivers. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 38, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestvold, K.; Stavem, K. Determinants of Health-Related Quality of Life 22 Years after Hospitalization for Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Inj. 2009, 23, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, A.C.; Haagsma, J.A.; Andriessen, T.M.J.C.; Vos, P.E.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Van Beeck, E.F.; Polinder, S. Health-Related Quality of Life after Mild, Moderate and Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Patterns and Predictors of Suboptimal Functioning during the First Year after Injury. Injury 2015, 46, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brands, I.; Köhler, S.; Stapert, S.; Wade, D.; Van Heugten, C. Influence of Self-Efficacy and Coping on Quality of Life and Social Participation after Acquired Brain Injury: A 1-Year Follow-up Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 2327–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grauwmeijer, E.; Heijenbrok-Kal, M.H.; Ribbers, G.M. Health-Related Quality of Life 3 Years after Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Prospective Cohort Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.B.; Feng, Z.; Fan, Y.C.; Xiong, Z.Y.; Huang, Q.W. Health-Related Quality-of-Life after Traumatic Brain Injury: A 2-Year Follow-up Study in Wuhan, China. Brain Inj. 2012, 26, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucciarelli, G.; Lee, C.S.; Lyons, K.S.; Simeone, S.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E. Quality of Life Trajectories Among Stroke Survivors and the Related Changes in Caregiver Outcomes: A Growth Mixture Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindel, D.; Schneider, A.; Grittner, U.; Jöbges, M.; Schenk, L. Quality of Life after Stroke Rehabilitation Discharge: A 12-Month Longitudinal Study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butsing, N.; Tipayamongkholgul, M.; Ratanakorn, D.; Suwannapong, N.; Bundhamcharoen, K. Social Support, Functional Outcome and Quality of Life among Stroke Survivors in an Urban Area. J. Pacific Rim Psychol. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdugo, M.Á.; Fernández, M.; Gómez, L.E.; Amor, A.M.; Aza, A. Predictive Factors of Quality of Life in Acquired Brain Injury. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2019, 19, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomberg, T.; Toomela, A.; Ennok, M.; Tikk, A. Changes in Coping Strategies, Social Support, Optimism and Health-Related Quality of Life Following Traumatic Brain Injury: A Longitudinal Study. Brain Inj. 2007, 21, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C.R.; Wrigley, M.; Yoels, W.; Fine, P.R. Explaining Quality of Life for Persons with Traumatic Brain Injuries 2 Years after Injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1995, 76, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshchi, S.G.; De Angelis, S.; Morone, G.; Panigazzi, M.; Persechino, B.; Tramontano, M.; Capodaglio, E.; Zoccolotti, P.; Paolucci, S.; Iosa, M. Return to Work and Quality of Life after Stroke in Italy: A Study on the Efficacy of Technologically Assisted Neurorehabilitation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.M.; Tsai, C.C.; Chung, C.Y.; Chen, C.L.; Wu, K.P.H.; Chen, H.C. Potential Predictors for Health-Related Quality of Life in Stroke Patients Undergoing Inpatient Rehabilitation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Steinbüchel, N.; Wilson, L.; Gibbons, H.; Hawthorne, G.; Höfer, S.; Schmidt, S.; Bullinger, M.; Maas, A.; Neugebauer, E.; Powell, J.; et al. Quality of Life after Brain Injury (QOLIBRI): Scale Validity and Correlates of Quality of Life. J. Neurotrauma 2010, 27, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, H.M.; Nguyen, L.H.; Tran, T.H.; Pham, K.T.H.; Phan, H.T.; Nguyen, H.N.; Tran, B.X.; Latkin, C.A.; Ho, C.S.H.; Ho, R.C.M. Effects of Chronic Comorbidities on the Health-Related Quality of Life among Older Patients after Falls in Vietnamese Hospitals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.Z.; Xiang, Y.T.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, S.; Ungvari, G.S.; Chiu, H.F.K.; Tang, W.K.; Wang, Y.L.; Zhao, X.Q.; et al. Depression after Minor Stroke: The Association with Disability and Quality of Life—A 1-Year Follow-up Study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 31, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, L. Factors Associated with Quality of Life Early after Ischemic Stroke: The Role of Resilience. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2019, 26, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapport, L.J.; Wong, C.G.; Hanks, R.A. Resilience and Well-Being after Traumatic Brain Injury. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goverover, Y.; Chiaravalloti, N. The Impact of Self-Awareness and Depression on Subjective Reports of Memory, Quality-of-Life and Satisfaction with Life Following TBI. Brain Inj. 2014, 28, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aza, A.; Verdugo, M.Á.; Orgaz, M.B.; Fernández, M.; Amor, A.M. Adaptation and Validation of the Self-Report Version of the Scale for Measuring Quality of Life in People with Acquired Brain Injury (CAVIDACE). Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1107–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aza, A.; Verdugo, M.Á.; Orgaz, M.B.; Andelic, N.; Fernández, M.; Forslund, M.V. The Predictors of Proxy- and Self-Reported Quality of Life among Individuals with Acquired Brain Injury. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdugo, M.A.; Aza, A.; Orgaz, M.B.; Fernández, M.; Amor, A.M. Longitudinal Study of Quality of Life in Acquired Brain Injury: A Self- and Proxy-Report Evaluation. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. in press.

- Fernández, M.; Gómez, L.E.; Arias, V.B.; Aguayo, V.; Amor, A.M.; Andelic, N.; Verdugo, M.A. A New Scale for Measuring Quality of Life in Acquired Brain Injury. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diez-Quevedo, C.; Rangil, T.; Sanchez-Planell, L.; Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. Validation and Utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire in Diagnosing Mental Disorders in 1003 General Hospital Spanish Inpatients. Psychosom. Med. 2001, 63, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigatano, G.P.; Bruna, O.; Mataro, M.; Muñoz, J.M.; Fernández, S.; Junque, C. Initial Disturbances of Consciousness Resultant Impaired Awareness in Spanish Patient with Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 1998, 13, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintala, D.H.; Novy, D.M.; Garza, H.M.; Young, M.E.; High, W.M.; Chiou-Tan, F.Y. Psychometric Properties of a Spanish-Language Version of the Community Integration Questionnaire (CIQ). Rehabil. Psychol. 2002, 47, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, A.M.; Fuchs, K.L.; High, W.M.; Hall, K.M.; Kreutzer, J.S.; Rosenthal, M. The Community Integration Questionnaire Revisited: Assessment of Factor Structure and Validity. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1999, 80, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a New Resilience Scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, I.G.; Sarason, B.R.; Shearin, E.N.; Pierce, G.R. A Brief Measure of Social Support: Practical and Theoretical Implications. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1987, 4, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Laurence Earlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L.E.; Verdugo, M.Á.; Arias, B.; Navas, P.; Schalock, R.L. The Development and Use of Provider Profiles at the Organizational and Systems Level. Eval. Program Plan. 2013, 40, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemse-van Son, A.H.P.; Ribbers, G.M.; Hop, W.C.J.; Stam, H.J. Community Integration Following Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Longitudinal Investigation. J. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 41, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdugo, M.Á. Conceptos Clave Que Explican Los Cambios En Las Discapacidades Intelectuales y Del Desarrollo En España. Siglo Cero 2018, 49, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, D.G.; Cisneros, L.V.D.; Román, C.G. The Influence of Community Social Support in the Quality of Life of People with Disabilities. Siglo Cero 2020, 51, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwitz, J.H.; Sima, A.P.; Kreutzer, J.S.; Dreer, L.E.; Bergquist, T.F.; Zafonte, R.; Johnson-Greene, D.; Felix, E.R. Longitudinal Examination of Resilience after Traumatic Brain Injury: A Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, K.H.; Blom, E.; Kwa, V.I.H. Predictors of Quality of Life 1 Year after Minor Stroke or TIA: A Prospective Single-Centre Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsyben, A.; Guilfoyle, M.; Timofeev, I.; Anwar, F.; Allanson, J.; Outtrim, J.; Menon, D.; Hutchinson, P.; Helmy, A. Spectrum of Outcomes Following Traumatic Brain Injury—Relationship between Functional Impairment and Health-Related Quality of Life. Acta Neurochir. 2018, 160, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matérne, M.; Strandberg, T.; Lundqvist, L.O. Change in Quality of Life in Relation to Returning to Work after Acquired Brain Injury: A Population-Based Register Study. Brain Inj. 2018, 32, 1731–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuluunbaatar, E.; Chou, Y.J.; Pu, C. Quality of Life of Stroke Survivors and Their Informal Caregivers: A Prospective Study. Disabil. Health J. 2016, 9, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariello, A.N.; Perrin, P.B.; Rodríguez-Agudelo, Y.; Plaza, S.L.O.; Quijano-Martinez, M.C.; Arango-Lasprilla, J.C. A Multi-Site Study of Traumatic Brain Injury in Mexico and Colombia: Longitudinal Mediational and Cross-Lagged Models of Family Dynamics, Coping, and Health-Related Quality of Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, E.; Gómez, L.E.; Alcedo, M.Á. Enfermedades Raras y Discapacidad Intelectual: Evaluación de La Calidad de Vida de Niños y Jóvenes. Siglo Cero 2016, 47, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Jiang, Y. Determinants of Quality of Life in Patients with Hemorrhagic Stroke: A Path Analysis. Medicine 2019, 98, e13928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic and Clinical Variables | Patients with 12 Months Follow-Up (n = 203) | Patients without Complete Follow-Up (n = 402) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | 203 | 400 | χ² = 1.87 |

| Male | 130 (64%) | 243 (60.8%) | |

| Female | 73 (36%) | 157 (39.3%) | |

| Age (years) | 203 | 396 | t394 = −0.12 |

| Mean (SD) | 53.01 (14.44) | 54.83 (14.47) | |

| Range | 18–86 | 18–91 | |

| Civil status | 198 | 391 | χ² = 2.46 |

| Single/separated/divorced/window(er) | 107 (54%) | 196 (50.1%) | |

| Married/cohabitating | 91 (46%) | 195 (49.9%) | |

| Educational level | 190 | 369 | χ² = 1.02 |

| Without education/none | 14 (7.4%) | 30 (8.1%) | |

| Primary education | 60 (31.6%) | 116 (31.4%) | |

| Secondary education | 64 (33.7%) | 117 (31.7%) | |

| Higher education | 52 (27.4%) | 106 (28.7%) | |

| Prior employment status | 200 | 383 | χ² = 2.58 |

| Not active/unemployed | 63 (31.5%) | 135 (25.2%) | |

| Employed/student | 137 (68,5%) | 248 (64.8%) | |

| Current employment status | 203 | 386 | χ² = 0.65 |

| Not active/unemployed | 199 (98%) | 376 (97.4%) | |

| Employed/student | 4 (2%) | 10 (2.6%) | |

| Type of home | 122 | 251 | χ² = 0.90 |

| Independent flat | 12 (9.8%) | 29 (11.6%) | |

| Residential center | 18 (14.8%) | 39 (15.5%) | |

| Family home/sheltered flat | 92 (75.4%) | 183 (72.9%) | |

| Level support | 189 | 355 | χ² = 9.24 * |

| Intermittent | 20 (10.6%) | 42 (11.6%) | |

| Limited | 12 (6.3%) | 38 (10.5%) | |

| Extensive | 50 (26.5%) | 98 (27.0%) | |

| Generalized | 107 (56.6%) | 185 (51.0%) | |

| Loss of legal capacity | 191 | 369 | χ² = 3.91 |

| No | 127 (66.5%) | 262 (71%) | |

| Yes | 64 (33.5%) | 107 (29%) | |

| Dependence recognized | 194 | 370 | χ² = 0.00 |

| No | 44 (22.7%) | 84 (22.7%) | |

| Yes | 150 (77.3%) | 286 (77.3%) | |

| Degree of dependence | 153 | 276 | χ² = 1.97 |

| Grade I moderate dependency | 24 (15.2%) | 40 (14.5%) | |

| Grade II severe dependency | 51 (33.3%) | 102 (37.0%) | |

| Grade III major dependency | 78 (51%) | 134 (48.6%) | |

| Time since the injury (years) | 194 | 373 | t371 = 10.95 ** |

| Mean (SD) | 8.25 (7.83) | 7.20 (6.98) | |

| Range | 0.5–47.5 | 0.5–47.5 | |

| Location of the injury | 191 | 358 | χ² = 4.90 * |

| One hemisphere | 121 (63.4%) | 245 (68.4%) | |

| Both hemispheres | 70 (36.6%) | 113 (31.6%) | |

| Etiology of the injury | 201 | 390 | χ² = 24.30 *** |

| Stroke | 112 (55.7%) | 239 (61.3%) | |

| Traumatic brain injury | 66 (32.8%) | 93 (23.8%) | |

| Cerebral anoxia | 10 (5%) | 16 (4.1%) | |

| Cerebral tumors | 6 (3%) | 17 (4.4%) | |

| Infection diseases | 2 (1%) | 8 (2.1%) | |

| Other | 5 (2.5%) | 17 (4.4%) | |

| Comorbidity (health conditions) | 203 | 393 | t400 = −2.12 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.35 (2.49) | 5.01 (2.44) | |

| Range | 0–12 | 0–12 | |

| Type of center | 171 | 313 | χ² = 23.36 *** |

| Day center | 101 (59.1%) | 146 (46.6%) | |

| Rehabilitation center | 70 (40.9%) | 167 (53.4%) |

| Statistics | EW | IR | MW | PD | PW | SD | SI | RI | Total QoL Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. items | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 40 |

| Mean | 11.23 | 10.25 | 12.33 | 9.55 | 10.93 | 10.26 | 9.27 | 12.06 | 105.11 |

| SD | 2.83 | 3.65 | 3.36 | 3.39 | 3.10 | 3.75 | 3.65 | 2.90 | 15.51 |

| Range of scores | 1–15 | 0–15 | 0–15 | 0–15 | 0–15 | 0–15 | 0–15 | 3–15 | 71–135 |

| Skewness | −0.71 | −0.35 | −1.57 | −0.37 | −0.38 | −0.46 | −0.20 | −0.94 | 0.07 |

| Kurtosis | 0.26 | −0.68 | 2.26 | −0.44 | −0.32 | −0.75 | −0.42 | 0.22 | −0.60 |

| Domain | ABI 3 Years Ago or Less (n = 63) | ABI More Than 3 Years Ago (n = 131) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | Effect Size | Baseline | One- Year Follow-Up | t | Effect size | Baseline | One- Year Follow-Up | |

| EW | t(57) = −9.42 ** | 0.14 | 10.48 (3.29) | 11.72 (2.88) | t(95) = −0.05 | 0.00 | 10.98 (2.84) | 11.01 (2.81) |

| IR | t(54) = 0.46 | 0.01 | 11.29 (3.09) | 10.96 (3.31) | t(97) = −1.17 | 0.01 | 9.55 (3.68) | 9.92 (3.63) |

| MW | t(56) = −0.07 | 0.00 | 12.28 (2.80) | 12.40 (3.31) | t(96) = −2.82 | 0.03 | 11.88 (3.05) | 12.38 (3.37) |

| PD | t(57) = −1.35 | 0.02 | 9.22 (3.52) | 9.81 (3.65) | t(98) = −3.86 * | 0.04 | 8.82 (2.98) | 9.39 (3.31) |

| PW | t(57) = −0.01 | 0.00 | 11.31 (2.93) | 11.36 (3.21) | t(92) = 0.00 | 0.00 | 10.61 (2.81) | 10.60 (3.10) |

| SD | t(55) = 0.04 | 0.00 | 11.02 (3.01) | 10.91 (3.97) | t(95) = −1.79 | 0.02 | 9.38 (3.89) | 9.87 (3.60) |

| SI | t(57) = −0.51 | 0.01 | 8.74 (4.04) | 9.19 (3.65) | t(97) = −1.64 | 0.02 | 8.93 (3.97) | 9.40 (3.51) |

| RI | t(55) = 0.29 | 0.00 | 12.64 (2.49) | 12.39 (3.42) | t(95) = −0.01 | 0.00 | 11.85 (2.76) | 11.88 (2.63) |

| Total | t(33) = 0.03 | 0.00 | 103.44 (14.14) | 102.91 (14.65) | t(95) = −1.79 | 0.03 | 101.91 (14.73) | 103.80 (15.48) |

| EW | IR | MW | PD | PW | SD | SI | RI | Total QoL Index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Variables | |||||||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Age 0 = ≤50 1 = >50 | η2 = 0.03 * 10.96 (3.25) 9.74 (4.02) | ||||||||

| Civil status 0 = Single/separated/divorced 1 = Married/cohabitating | η2 = 0.03 * 10.76 (2.77) 11.69 (2.84) | ||||||||

| Educational level 1 = Without education/none 2 = Primary education 3 = Secondary education 4 = Higher education | η2 = 0.05 * 8.17 (3.41) 9.57 (3.89) 10.41 (3.48) 11.23 (3.88) | ||||||||

| Prior employment | |||||||||

| Type of home 1 = Independent flat 2 = Residential center 3 = Family/sheltered | η2 = 0.15 *** 12.82 (1.89) 8.87 (3.91) 12.66 (3.63) | η2 = 0.08 * 12.64 (1.69) 9.93 (3.81) 12.24 (2.85) | |||||||

| Injury-related variables | |||||||||

| Level of support | |||||||||

| Loss of legal capacity 0 = No 1 = Yes | η2 = 0.03 * 10.69 (3.40) 9.26 (4.02) | η2 = 0.06 ** 10.11 (3.29) 8.28 (3.44) | |||||||

| Degree of dependency 1 = Grade I moderate dependency 2 = Grade II severe dependency 3 = Grade I major dependency | η2 = 0.02 * 11.81 (3.03) 9.29 (3.69) 9.23 (3.85) | η2 = 0.02 ** 116.28 (14.34) 102.58 (14.82) 100.68 (15.15) | |||||||

| Time since injury | |||||||||

| Location of the injury 0 = Unilateral 1 = Bilateral | η2 = 0.03 * 10.71 (3.56) 9.54 (3.44) | η2 = 0.04 * 9.98 (3.46) 8.63 (3.12) | η2 = 0.03 * 9.82 (3.63) 8.47 (3.27) | ||||||

| Etiology of the injury | |||||||||

| Comorbidity 0 = ≤5 1 = >5 | η2 = 0.04 ** 11.70 (2.55) 10.52 (3.09) | η2 = 0.04 ** 10.14 (3.18) 8.69 (3.54) | η2 = 0.04 * 10.83 (3.63) 9.40 (3.79) | η2 = 0.04 ** 9.89 (3.67) 8.37 (3.45) | η2 = 0.04 * 107.79 (15.00) 101.77 (15.61) | ||||

| Rehabilitation variable | |||||||||

| Type of center 0 = Day center 1 = Rehabilitation center | η2 = 0.05 ** 9.49 (3.93) 11.12 (3.22) | ||||||||

| Personal and social variables (baseline) | |||||||||

| Self-awareness | |||||||||

| Depression 1 = Low 2 = Intermediate 3 = High | η2 = 0.14 *** 12.13 (2.59) 11.56 (2.27) 9.18 (3.33) | η2 = 0.06 ** 10.34 (3.37) 9.54 (3.21) 7.85 (3.70) | η2 = 0.06 * 107.23 (15.12) 106.48 (17.80) 96.95 (13.32) | ||||||

| Resilience 1 = Low 2 = Intermediate 3 = High | η2 = 0.06 * 10.40 (2.57) 11.14 (2.79) 12.25 (2.62) | η2 = 0.07 ** 8.63 (4.02) 10.34 (3.21) 11.27 (3.77) | η2 = 0.04 * 11.09 (3.97) 12.69 (2.67) 12.62 (3.74) | η2 = 0.05 * 8.15 (3.29) 9.74 (3.19) 10.14 (3.55) | η2 = 0.12 *** 94.81 (12.00) 105.87 (13.05) 110.03 (18.93) | ||||

| Social support 1 = Low 2 = Intermediate 3 = High | η2 = 0.05 * 9,45 (4.32) 10.30 (3.50) 11.54 (2.96) | η2 = 0.05 * 11.21 (3.27) 11.91 (3.08) 12.92 (2.17) | |||||||

| Satisfaction with social support 1 = Low 2 = Intermediate 3 = High | η2 = 0.10 ** 9.64 (2.43) 11.13 (2.78) 12.08 (2.79) | η2 = 0.08 ** 8.92 (3.31) 9.48 (3.61) 11.31 (3.33) | η2 = 0.08 ** 10.44 (4.24) 12.17 (2.88) 13.08 (3.06) | η2 = 0.06 * 9.54 (3.01) 10.58 (2.97) 11.65 (3.16) | η2 = 0.05 * 7.81 (3.42) 8.92 (3.67) 9.95 (3.74) | η2 = 0.15 *** 10.35 (3.06) 11.51 (2.97) 13.25 (2.42) | η2 = 0.09 ** 95.61 (14.72) 104.36 (16.63) 109.02 (13.65) | ||

| Community integration 1 = Low 2 = Intermediate 3 = High | η2 = 0.09 ** 8.50 (4.20) 10.49 (3.08) 11.32 (3.23) | η2 = 0.06 ** 11.20 (3.96) 12.58 (3.26) 13.20 (2.31) | η2 = 0.13 *** 8.14 (3.37) 9.26 (3.26) 11.24 (2.43) | η2 = 0.14 *** 8.89 (3.66) 9.83 (3.84) 12.36 (2.70) | η2 = 0.14 *** 8.89 (3.66) 9.83 (3.84) 12.36 (2.70) | η2 = 0.13 *** 7.34 (3.71) 9.47 (3.39) 10.80 (3.11) | |||

| Personal and social variables (one-year) | |||||||||

| Self-awareness | |||||||||

| Depression 1 = Low 2 = Intermediate 3 = High | η2 = 0.17 *** 12.16 (2.50) 11.24 (2.66) 8.65 (3.01) | η2 = 0.08 ** 11.20 (3.66) 10.00 (3.93) 8.15 (3.23) | η2 = 0.08 * 106.00 (16.78) 108.37 (14.40) 97.15 (9.60) | ||||||

| Resilience 1 = Low 2 = Intermediate 3 = High | η2 = 0.11 ** 10.14 (2.87) 10.82 (2.90) 12.62 (2.44) | η2 = 0.08 * 10.59 (4.00) 12.30 (3.06) 13.27 (2.99) | η2 = 0.28 *** 6.90 (3.49) 9.13 (2.87) 12.00 (2.60) | η2 = 0.11 ** 8.14 (3.97) 9.97 (3.37) 11.69 (3.28) | η2 = 0.17 *** 7.33 (3.10) 9.27 (3.06) 11.53 (3.70) | η2 = 0.05 * 11.19 (3.08) 11.73 (2.89) 13.03 (3.06) | η2 = 0.10 * 96.29 (12.28) 106.10 (14.09) 110.71 (17.17) | ||

| Social support | |||||||||

| Satisfaction with social support 1 = Low 2 = Intermediate 3 = High | η2 = 0.06 * 10.07 (3.13) 10.88 (2.70) 11.98 (2.73) | η2 = 0.15 *** 6.88 (3.56) 10.03 (3.91) 11.30 (3.44) | η2 = 0.14 ** 9.81 (2.97) 9.80 (3.19) 12.16 (2.75) | η2 = 0.16 *** 9.25 (3.32) 11.85 (2.85) 12.79 (2.47) | η2 = 0.08 * 96.46 (16.27) 106.42 (14.79) 108.72 (14.12) | ||||

| Community integration 1 = Low 2 = Intermediate 3 = High | η2 = 0.13 *** 8.47 (3.96) 10.35 (3.82) 11.76 (2.63) | η2 = 0.08 * 11.11 (4.17) 12.68 (3.27) 13.30 (2.04) | η2 = 0.17 *** 8.06 (3.42) 8.73 (3.04) 11.16 (2.74) | η2 = 0.11 ** 8.63 (3.32) 10.35 (3.46) 11.51 (3.57) | η2 = 0.07 * 8.38 (4.14) 9.22 (3.38) 10.57 (3.02) | η2 = 0.07 * 10.82 (3.49) 11.56 (3.05) 12.77 (2.47) | |||

| Dependent Variables | Variables (Final Model) | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | 95 CI Lower/Upper Bound | t | p | F Change | Change Adjusted R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E. | Beta | |||||||

| EW | Civil status | 1.31 | 0.55 | 0.24 | 0.21/2.42 | 2.38 | 0.020 | 4.97 * | 0.05 |

| Depression baseline | −1.27 | 0.39 | −0.33 | −2.05/−0.49 | −0.33 | 0.002 | 16.06 *** | 0.17 | |

| Resilience 12 m | 1.34 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.52/2.17 | 3.26 | 0.002 | 10.63 ** | 0.10 | |

| Total | 0.32 | ||||||||

| IR | IR baseline | 0.47 | 0.09 | 0.48 | 0.30/0.64 | 5.57 | <0.001 | 55.14 *** | 0.38 |

| Satisfaction with social support 12 m | 1.14 | 0.42 | 0.23 | 0.31/1.98 | 2.72 | 0.008 | 9.39 ** | 0.06 | |

| Community integration 12 m | 1.00 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.24/1.77 | 2.62 | 0.011 | 6.85 * | 0.04 | |

| Total | 0.48 | ||||||||

| MW | Community integration 12 m | 1.67 | 0.64 | 0.36 | 0.38/2.96 | 2.60 | 0.012 | 6.77 * | 0.11 |

| Total | 0.11 | ||||||||

| PD | Loss of legal capacity | −1.19 | 0.58 | −0.16 | −2.35/−0.04 | −2.05 | 0.043 | 7.51 ** | 0.06 |

| Community integration baseline | 1.08 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.36/1.79 | 3.00 | 0.004 | 16.83 *** | 0.13 | |

| Resilience 12 m | 2.29 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 1.46/3.12 | 5.47 | <0.001 | 29.94 *** | 0.18 | |

| Total | 0.37 | ||||||||

| PW | PW baseline | 0.47 | 0.10 | 0.43 | 0.27/0.67 | 4.69 | <0.001 | 28.55 *** | 0.23 |

| Satisfaction with social support 12 m | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.23 | 0.19/1.77 | 2.45 | 0.016 | 6.09 * | 0.05 | |

| Total | 0.28 | ||||||||

| SD | SD baseline | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.27 | 0.09/0.45 | 2.93 | 0.004 | 20.42 *** | 0.16 |

| Educational level | 1.00 | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.34/1.67 | 3.00 | 0.003 | 7.96 ** | 0.06 | |

| Community integration baseline | 0.92 | 0.44 | 0.20 | 0.05/1.79 | 2.10 | 0.039 | 6.32 * | 0.04 | |

| Resilience 12 m | 1.03 | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.10/1.96 | 2.19 | 0.031 | 4.79 * | 0.03 | |

| Total | 0.29 | ||||||||

| SI | SI baseline | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.35 | 0.18/0.47 | 4.40 | <0.001 | 23.80 *** | 0.16 |

| Comorbidity | −1.21 | 0.58 | −0.17 | −2.36/−0.06 | −2.09 | 0.039 | 6.62 * | 0.05 | |

| Resilience 12 m | 1.74 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.90/2.58 | 4.09 | <0.001 | 16.72 *** | 0.10 | |

| Total | 0.31 | ||||||||

| RI | Satisfaction with social support baseline | 1.89 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.83/2.95 | 3.60 | 0.001 | 16.14 *** | 0.27 |

| Community integration baseline | 1.22 | 0.58 | 0.28 | 0.06/2.39 | 2.12 | 0.041 | 4.49 * | 0.06 | |

| Total | 0.33 | ||||||||

| Total QoL Index | Total baseline | 0.55 | .11 | 0.53 | 0.33/0.76 | 5.00 | <0.001 | 25.03 *** | 0.17 |

| Dependency level | −8.27 | 2.01 | −0.39 | −12.27/−4.27 | −4.11 | <0.001 | 15.61 *** | 0.15 | |

| Depression baseline | −5.63 | 2.26 | −0.24 | −10.14/−1.13 | −2.49 | 0.015 | 8.12 ** | 0.07 | |

| Satisfaction with social support baseline | 4.50 | 2.04 | 0.21 | 0.43/8.57 | 2.20 | 0.031 | 4.84 * | 0.04 | |

| Total | 0.43 | ||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aza, A.; Verdugo, M.Á.; Orgaz, M.B.; Amor, A.M.; Fernández, M. Predictive Factors of Self-Reported Quality of Life in Acquired Brain Injury: One-Year Follow-Up. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030927

Aza A, Verdugo MÁ, Orgaz MB, Amor AM, Fernández M. Predictive Factors of Self-Reported Quality of Life in Acquired Brain Injury: One-Year Follow-Up. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(3):927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030927

Chicago/Turabian StyleAza, Alba, Miguel Á. Verdugo, María Begoña Orgaz, Antonio M. Amor, and María Fernández. 2021. "Predictive Factors of Self-Reported Quality of Life in Acquired Brain Injury: One-Year Follow-Up" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 3: 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030927

APA StyleAza, A., Verdugo, M. Á., Orgaz, M. B., Amor, A. M., & Fernández, M. (2021). Predictive Factors of Self-Reported Quality of Life in Acquired Brain Injury: One-Year Follow-Up. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 927. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030927