Preferences and Experiences of People with Chronic Illness in Using Different Sources of Health Information: Results of a Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

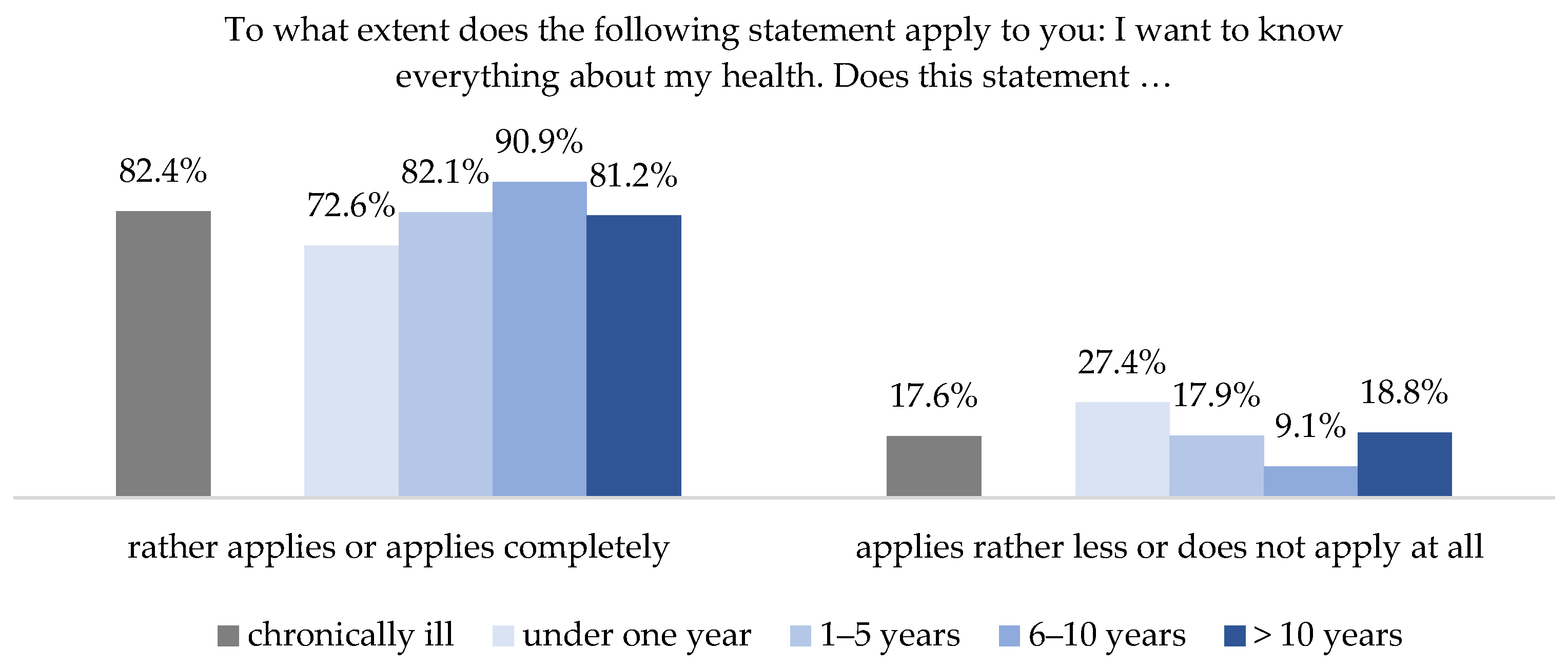

3.1. Interest in Health Information

“The patient is already ill and must first cope with the disease and is then bombarded with specialist information (.), which has nothing to do with the individual patient.”(FG 4)

“Yes definitely. Dealing (with health information) has become the central focus of my life. Every bit of information and every source is checked over and over.”(FG 7)

“I would say it has become more intense, more positive, much more targeted. So not taking in everything anymore, but really only targeted.”(FG 2)

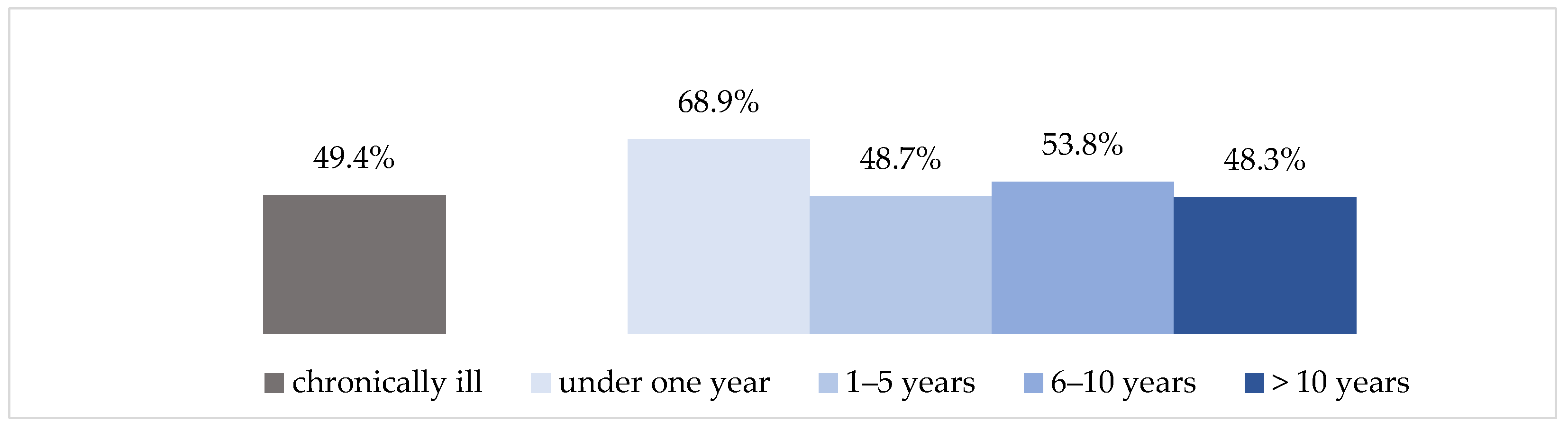

3.2. Health Literacy among People with Chronic Illness

“So, judging I sometimes find difficult because there is always this opinion and that opinion (...) That’s why it is sometimes really hard to judge what’s good for me and not and what I should do now.”(FG 1)

“I don’t need to read this page any further, because it is all about selling me something. You have to be very careful.”(FG 2)

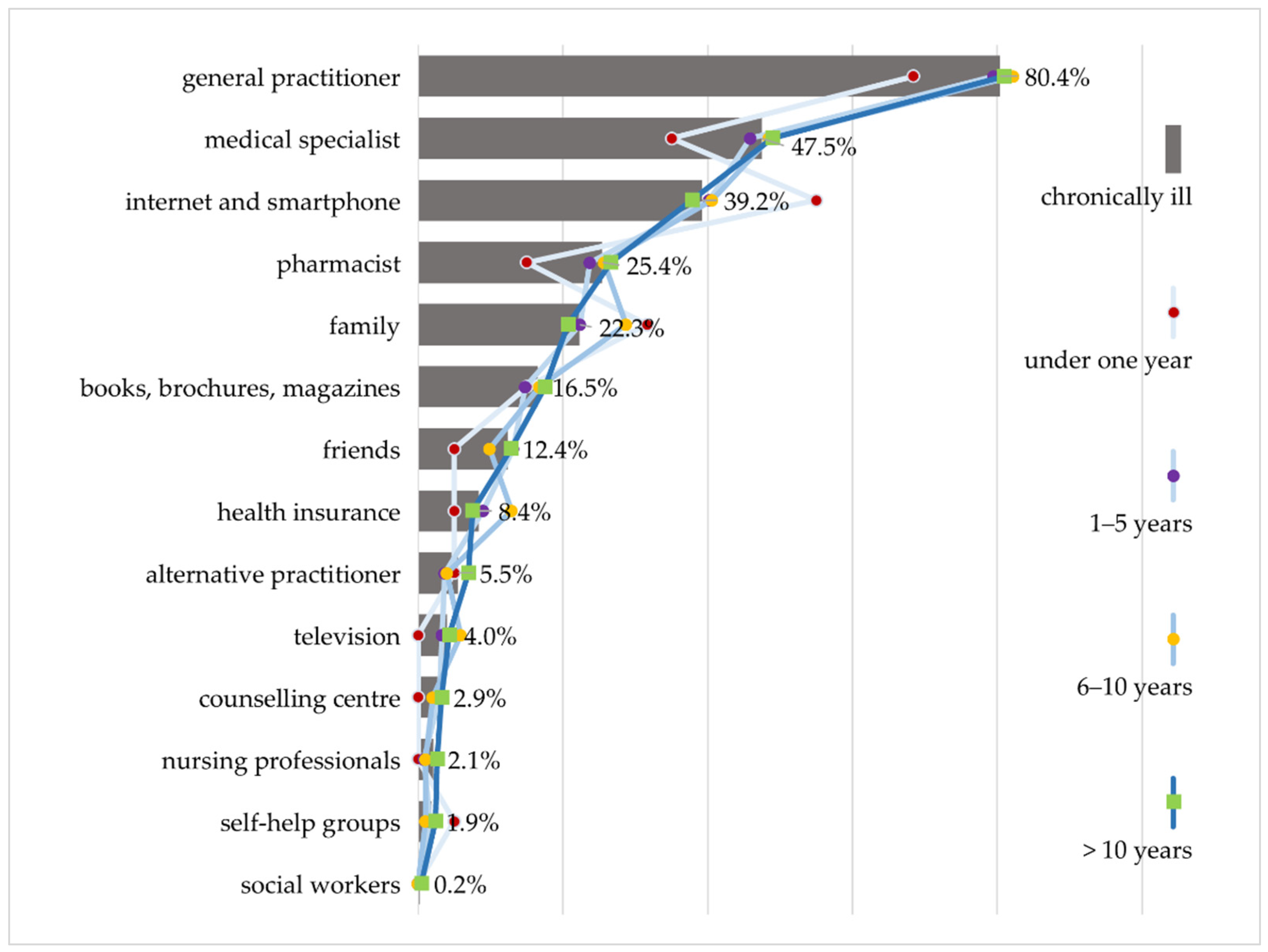

3.3. Preferred Sources of Information

“So, I am very much googling and very often on Wikipedia. If a clinical picture comes up somewhere that affects not only me but also my family (…). When mom has a weird cough, I’m already looking, what could it be?”(FG 1)

“When I was diagnosed, when the doctor told me what I had, I got on the Internet and researched what it meant. She did tell me a few things (...), but then I got more detailed information from the Internet.”(FG 5)

“If I am prescribed something new, because I receive medication from different doctors, then (...) the pharmacy is my point of contact to find out if the medications are all compatible (...) And I have a really competent pharmacy (...) that checks the medications against each other.”(FG 2)

“Yes, then I show it to my sons, and they tell me what it means. I don’t understand everything, and they explain it to me.”(FG 2)

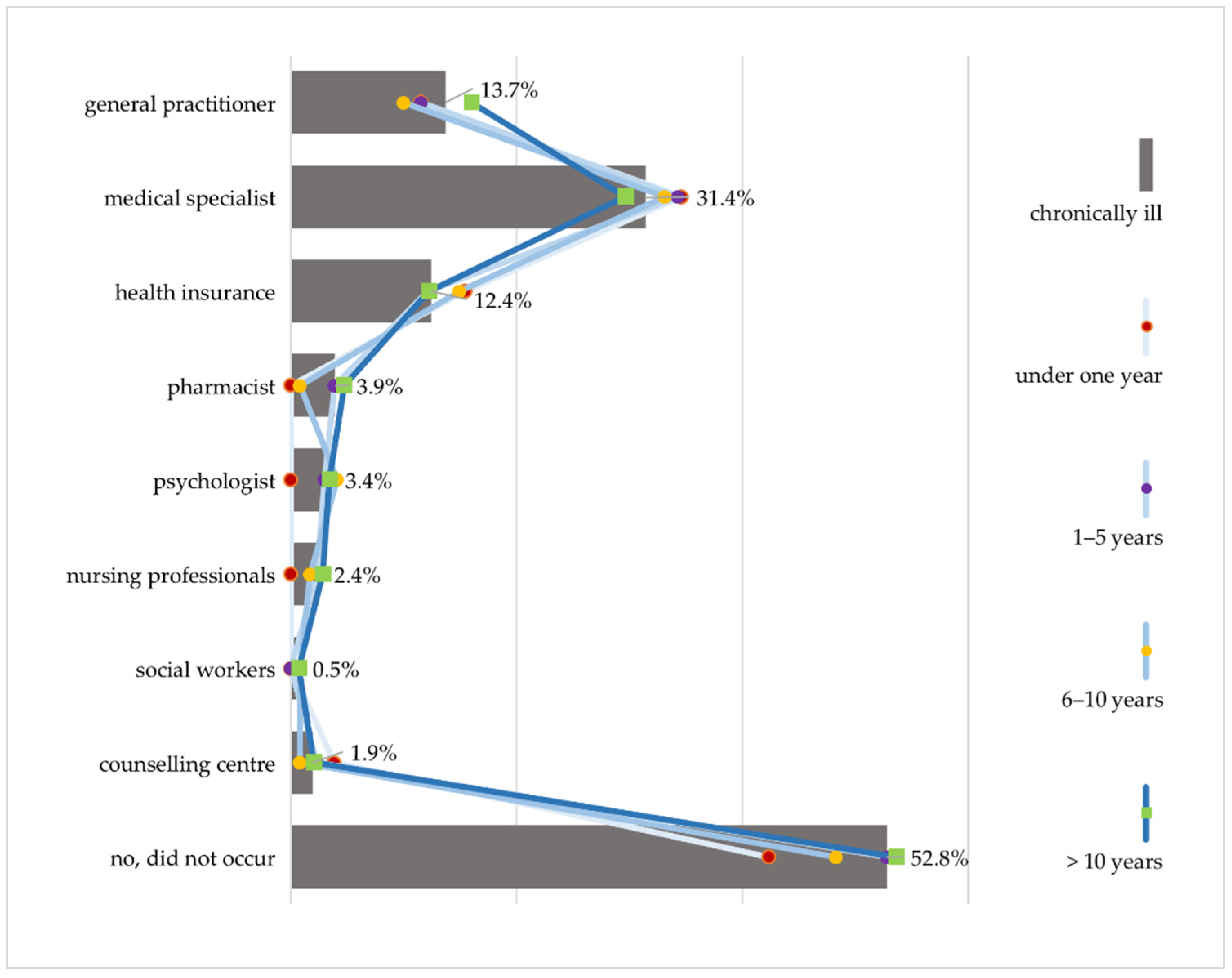

3.4. Experience in Searching for and Dealing with Health Information

3.4.1. Trust and Competence

“You start to search around when you feel uncertain and don’t know what to do and reach a point where you just feel so alone, and that’s when something has to happen. You either begin to look for other doctors or whatever.”(FG 7)

“When you search for such and such on the Internet, the first things that always appear are the worst things you could have, and that’s more unsettling than it is reassuring. That’s why it’s better to go to the doctor.”(FG 6)

“My daughter always says: Stay away from the Internet, go to the doctor instead. If you Google, you’ll be dead in six months.”(FG 6)

“And then his (the physician’s) statements need to be checked. And I do check them now but didn’t ten years ago.”(FG 5)

3.4.2. Time

“But that’s just chop-chop: waiting three hours for five minutes, then you have a piece of paper in your hand with a medication and then you leave.”(FG 2)

“They don’t have any time. That’s why I (…) wrote down my questions beforehand, so I knew what to ask. But I still don’t have the feeling that I know everything I should, because they just didn’t take any time with me.”(FG 6)

“And then you’re considered the worst kind of patient if you’ve done your research beforehand! And oh brother, we’ve all gone through that at least once. When you already know a few things and go to the doctor—forget it, not a chance.”(FG 7)

“But then one page leads to another page and another and there’s more and more information (...) and you continue reading and suddenly there are 1000 tabs open and at the end you’re just confused.”(FG 7)

3.4.3. Comprehensibility of Information and Communication

“I once had a doctor, an orthopedist. The receptionist was there during the examination. The doctor just rattled off something in Latin, went out and then the receptionist said: Okay, I’ll translate for you, you probably didn’t understand anything.”(FG 7)

“We’re not supposed to understand, that’s why they also use the Latin medical terms. Patients are kept in the dark so they can’t raise any objections or take matters into their own hands, which could be considered contra-productive (...).”(FG 3)

“When my doctor or a specialist now throws around a medical term, I immediately say: What does that mean? If I don’t know something, I ask, but there are also people who are too afraid or shy to ask questions.”(FG 6)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

- Establish a trajectory-oriented information management that takes into account the ever-changing needs of people with chronic illness.

- Consider the mix of different information sources and, in addition to improving written information, pay particular attention to oral information and communication with health professionals.

- In doing so, foster the necessary structural changes and anchor skills and competencies required for information provision in the education and training of health care professionals.

- Establish special guidance systems and navigation aids for people with chronic illness that make it easier to find and use health information along the entire illness trajectory and thereby increasing health literacy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Personen mit Einem Lang Andauernden Gesundheitsproblem, Nach Geschlecht, Alter und Erwerbsstatus: Europäische Gesundheitsstatistiken. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/hlth_silc_04/default/table?lang=de (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Hyman, R.B.; Corbin, J. (Eds.) Chronic Illness; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, D. (Ed.) Bewältigung Chronischer Erkrankungen im Lebenslauf; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A.L.; Hildenbrand, A. Weiterleben Lernen: Verlauf und Bewältigung Chronischer Krankheit, 3rd ed.; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, D.; Haslbeck, J. Bewältigung Chronischer Krankheit. In Soziologie von Gesundheit und Krankheit; Richter, M., Hurrelmann, K., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; pp. 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth, A. Information Obesity; Chandos Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Okan, O.; Bollweg, T.M.; Berens, E.-M.; Hurrelmann, K.; Bauer, U.; Schaeffer, D. Coronavirus-Related Health Literacy: A Cross-Sectional Study in Adults during the COVID-19 Infodemic in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Infodemic management: A key component of the COVID-19 global response. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2020, 95, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, D. Chronische Krankheit und Health Literacy. In Health Literacy: Forschungsstand und Perspektiven, 1st ed.; Schaeffer, D., Pelikan, J.M., Eds.; Hogrefe: Bern, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, D.; Schmidt-Kaehler, S.; Dierks, M.-L.; Ewers, M.; Vogt, D. Strategiepapier #2 zu den Empfehlungen des Nationalen Aktionsplans. Gesundheitskompetenz in die Versorgung von Menschen mit Chronischer Erkrankung Integrieren; Nationaler Aktionsplan Gesundheitskompetenz: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, K.; van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rademakers, J.; Heijmans, M. Beyond Reading and Understanding: Health Literacy as the Capacity to Act. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rowlands, G.; Protheroe, P.; Saboga-Nunes, L.; van den Broucke, S.; Levin-Zamir, D.; Okan, O. Health literacy and chronic conditions: A life course perspective. In International Handbook of Health Literacy. Research, Practice and Policy across the Life-Span; Okan, O., Bauer, U., Levin-Zamir, D., Pinheiro, P., Sørensen, K., Eds.; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019; pp. 183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, D.; Vogt, D.; Berens, E.M.; Hurrelmann, K. Gesundheitskompetenz der Bevölkerung in Deutschland—Ergebnisbericht; Universität Bielefeld: Bielefeld, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, D.; Griese, L.; Berens, E.-M. Gesundheitskompetenz von Menschen mit Chronischer Erkrankung in Deutschland. Gesundheitswesen 2020, 82, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Röthlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Uiters, E.; et al. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mirzaei, A.; Aslani, P.; Luca, E.J.; Schneider, C.R. Predictors of Health Information-Seeking Behavior: Systematic Literature Review and Network Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e21680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.D.; Loiselle, C.G. Health information seeking behavior. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.A.; Moore, J.L.; Steege, L.M.; Koopman, R.J.; Belden, J.L.; Canfield, S.M.; Meadows, S.E.; Elliott, S.G.; Kim, M.S. Health information needs, sources, and barriers of primary care patients to achieve patient-centered care: A literature review. J. Health Inform. 2016, 22, 992–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, I.; Corsini, N.; Peters, M.D.J.; Eckert, M. A rapid review of consumer health information needs and preferences. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1634–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, E.; Czerwinski, F.; Rosset, M.; Seelig, M.; Suhr, R. Wie informieren sich die Menschen in Deutschland zum Thema Gesundheit? Erkenntnisse aus der ersten Welle von HINTS Germany. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2020, 63, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrelmann, K.; Klinger, J.; Schaeffer, D. Gesundheitskompetenz der Bevölkerung in Deutschland: Vergleich der Erhebungen 2014 und 2020; Universität Bielefeld, Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Gesundheitskompetenzforschung: Bielefeld, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, M.S.; Shaw, G. Health information seeking behaviour: A concept analysis. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2020, 37, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, D.; Dierks, M.L. Patientenberatung in Deutschland. In Lehrbuch Patientenberatung, 2nd ed.; Schaeffer, D., Schmidt-Kaehler, S., Eds.; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 159–183. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, W.; Amuta, A.O.; Jeon, K.C. Health information seeking in the digital age: An analysis of health information seeking behavior among US adults. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2017, 3, 1302785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Unending Work and Care: Managing Chronic Illness at Home; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Haslbeck, J. Medikamente und Chronische Krankheit. Selbstmanagementerfordernisse im Krankheitsverlauf aus Sicht der Erkrankten; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Engqvist Boman, L.; Sandelin, K.; Wengström, Y.; Silén, C. Patients’ learning and understanding during their breast cancer trajectory. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Longo, D.R.; Ge, B.; Radina, M.E.; Greiner, A.; Williams, C.D.; Longo, G.S.; Mouzon, D.M.; Natale-Pereira, A.; Salas-Lopez, D. Understanding breast-cancer patients’ perceptions: Health information-seeking behaviour and passive information receipt. J. Healthc. Commun. 2009, 2, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, L.; Hoffman-Goetz, L. A qualitative study of cancer information seeking among English-as-a-second-Language older Chinese immigrant women to canada: Sources, barriers, and strategies. J. Cancer Educ. 2011, 26, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagler, R.H.; Gray, S.W.; Romantan, A.; Kelly, B.J.; DeMichele, A.; Armstrong, K.; Schwartz, J.S.; Hornik, R.C. Differences in information seeking among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer patients: Results from a population-based survey. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 81 (Suppl. 1), S54–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalantzi, S.; Kostagiolas, P.; Kechagias, G.; Niakas, D.; Makrilakis, K. Information seeking behavior of patients with diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study in an outpatient clinic of a university-affiliated hospital in Athens, Greece. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Leary, K.A.; Estabrooks, C.A.; Olson, K.; Cumming, C. Information acquisition for women facing surgical treatment for breast cancer: Influencing factors and selected outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 69, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, D.; Moers, M. Bewältigung chronischer Krankheiten—Herausforderungen für die Pflege. In Handbuch Pflegewissenschaft; Schaffer, D., Wingenfeld, K., Eds.; Juventa: Weinheim, Germany, 2014; pp. 329–363. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.T. The Relationship between Health Management and Information Behavior over Time: A Study of the Illness Journeys of People Living with Fibromyalgia. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambrock, U. Die Suche nach Gesundheitsinformationen: Patientenperspektiven und Marktüberblick; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, E.; Hastall, M.R. Nutzung von Gesundheitsinformationen. In Handbuch Gesundheitskommunikation; Hurrelmann, K., Baumann, E., Eds.; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 451–466. [Google Scholar]

- Zare-Farashbandi, F.; Lalazaryan, A.; Rahimi, A.; Hasssanzadeh, A. The Effect of Contextual Factors on Health Information–Seeking Behavior of Isfahan Diabetic Patients. J. Hosp. Librariansh. 2016, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, C.-W.; Col, J.R.; Donald, M.; Dower, J.; Boyle, F.M. Health and social correlates of Internet use for diabetes information: Findings from Australia’s Living with Diabetes Study. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2015, 21, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuske, S.; Schiereck, T.; Grobosch, S.; Paduch, A.; Droste, S.; Halbach, S.; Icks, A. Diabetes-related information-seeking behaviour: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schaeffer, D.; Berens, E.-M.; Gille, S.; Griese, L.; Klinger, J.; de Sombre, S.; Vogt, D.; Hurrelmann, K. Gesundheitskompetenz der Bevölkerung in Deutschland vor und während der Corona Pandemie: Ergebnisse des HLS-GER 2; Universität Bielefeld, Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Gesundheitskompetenzforschung: Bielefeld, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, D.; Vogt, D.; Gille, S. Gesundheitskompetenz-Perspektive und Erfahrungen von Menschen mit chronischer Erkrankung; Universität Bielefeld: Bielefeld, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The HLS19 Consortium of the WHO Action Network M-POHL. International Report on the Methodology, Results, and Recommendations of the European Health Literacy Population Survey 2019–2021 (HLS19) of M-POHL; Austrian National Public Health Institute: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dierks, M.-L.; Kofahl, C. Die Rolle der gemeinschaftlichen Selbsthilfe in der Weiterentwicklung der Gesundheitskompetenz der Bevölkerung. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2019, 62, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Qualitative Sozialforschung: Eine Einführung, 8th ed.; Rowohlt Taschenbuch: Reinbek bei Hamburg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bury, M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol. Health Illn. 1982, 4, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, D.; Moers, M. Abschied von der Patientenrolle? Bewältigungshandeln im Verlauf chronischer Krankheit. In Bewältigung chronischer Krankheit im Lebenslauf, 1st ed.; Schaeffer, D., Ed.; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2009; pp. 111–139. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, P.; Asimakopoulou, K.; Scambler, S. Information seeking and use amongst people living with type 2 diabetes: An information continuum. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2012, 50, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.; Mühlhauser, I.; Steckelberg, A. Evidenzbasierte Gesundheitsinformation. In Handbuch Gesundheitskommunikation; Hurrelmann, K., Baumann, E., Eds.; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Oedekoven, M.; Herrmann, W.J.; Ernsting, C.; Schnitzer, S.; Kanzler, M.; Kuhlmey, A.; Gellert, P. Patients’ health literacy in relation to the preference for a general practitioner as the source of health information. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ebner, C.; Rohrbach-Schmidt, D. Berufliches Ansehen in Deutschland für die Klassifikation der Berufe 2010: Beschreibung der Methodischen Vorgehensweise, erste Deskriptive Ergebnisse und Güte der Messung; Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stiftung Gesundheitswissen. Statussymbol Gesundheit. Wie sich der soziale Status auf Prävention und Gesundheit Auswirken Kann: Gesundheitsbericht 2020 der Stiftung Gesundheitswissen; Stiftung Gesundheitswissen: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Link, E.; Baumann, E. Nutzung von Gesundheitsinformationen im Internet: Personenbezogene und motivationale Einflussfaktoren. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2020, 63, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Koch-Institut. Kommunikation und Information im Gesundheitswesen aus Sicht der Bevölkerung. Patientensicherheit und informierte Entscheidung (KomPaS): Sachbericht; Robert Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Marstedt, G. Das Internet: Auch Ihr Ratgeber für Gesundheitsfragen? Bevölkerungsumfrage zur Suche von Gesundheitsinformationen im Internet und zur Reaktion der Ärzte; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, E.; Czerwinski, F. Erst mal Doktor Google fragen? Nutzung Neuer Medien zur Information und zum Austausch über Gesundheitsthemen. In Gesundheitsmonitor 2015: Bürgerorientierung im Gesundheitswesen; Böcken, J., Braun, B., Meierjürgen, R., Eds.; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2015; pp. 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Thiel, R.; Deimel, L.; Schmidtmann, D.; Piesche, K.; Hüsing, T.; Rennoch, J.; Stroetmann, V.; Stroetmann, K. #SmartHealthSystems: Digitalisierungsstrategien im Internationalen Vergleich; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Kaehler, S.; Dadaczynski, K.; Gille, S.; Okan, O.; Schellinger, A.; Weigand, M.; Schaeffer, D. Gesundheitskompetenz: Deutschland in der digitalen Aufholjagd Einführung technologischer Innovationen greift zu kurz. Gesundheitswesen 2021, 83, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Hoti, K.; Hughes, J.D.; Emmerton, L. Dr Google and the consumer: A qualitative study exploring the navigational needs and online health information-seeking behaviors of consumers with chronic health conditions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Irving, G.; Neves, A.L.; Dambha-Miller, H.; Oishi, A.; Tagashira, H.; Verho, A.; Holden, J. International variations in primary care physician consultation time: A systematic review of 67 countries. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2019; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der Entwicklung im Gesundheitswesen. Koordination und Integration-Gesundheitsversorgung in einer Gesellschaft des Längeren Lebens. Sondergutachten 2009; SVR: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright, J.; Magee, J. Information for People Living with Conditions that Affect their Appearance: Report I. The Views and Experiences of Patients and the Health Professionals Involved in Their Care—A Qualitative Study; Picker Institute Europe: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hannawa, A.F.; Rothenfluh, F.B. Arzt-Patient-Interaktion. In Handbuch Gesundheitskommunikation; Hurrelmann, K., Baumann, E., Eds.; Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 110–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hinding, B.; Brünahl, C.A.; Buggenhagen, H.; Gronewold, N.; Hollinderbäumer, A.; Reschke, K.; Schultz, J.-H.; Jünger, J. Pilot implementation of the national longitudinal communication curriculum: Experiences from four German faculties. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2021, 38, Doc52. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers, S.L.; Kronenfeld, J.J. Chronic illness and health-seeking information on the Internet. Health 2007, 11, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griebler, R.; Straßmayr, C.; Mikšová, D.; Link, T.; Nowak, P. die Arbeitsgruppe Gesundheitskompetenz-Messung der ÖPGK. Gesundheitskompetenz in Österreich: Ergebnisse der Österreichischen Gesundheitskompetenzerhebung HLS19-AT; Bundesministerium für Soziales, Gesundheit, Pflege und Konsumentenschutz: Wien, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- De Gani, S.M.; Jaks, R.; Bieri, U.; Kocher, J.P. Health Literacy Survey Schweiz 2019–2021: Schlussbericht im Auftrag des Bundesamtes für Gesundheit BAG; Careum Stiftung: Zürich, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shiferaw, K.B.; Tilahun, B.C.; Endehabtu, B.F.; Gullslett, M.K.; Mengiste, S.A. E-health literacy and associated factors among chronic patients in a low-income country: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2020, 20, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, D.; Gille, S.; Berens, E.-M.; Griese, L.; Klinger, J.; Vogt, D.; Hurrelmann, K. Digitale Gesundheitskompetenz der Bevölkerung in Deutschland: Ergebnisse des HLS-GER 2. Gesundheitswesen 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Proportion/Mean (SD) | N |

|---|---|---|

| Age [min, max: 18–92] | 58.67 (16.63) | 1080 |

| 18–29 years | 7.3 | 79 |

| 30–45 years | 15.3 | 165 |

| 46–64 years | 36.1 | 390 |

| 65 years and older | 41.3 | 446 |

| Illness duration [min, max: 0–82] | 13.20 (11.72) | 1066 |

| less than one year | 2.4 | 26 |

| 1–5 years | 28.6 | 305 |

| 6–10 years | 11.3 | 121 |

| >10 years | 57.6 | 614 |

| Number of chronic diseases [min, max: 1–12] | 1086 | |

| one | 30.1 | 327 |

| more than one | 69.9 | 759 |

| Gender | 1084 | |

| male | 46.7 | 506 |

| female | 53.3 | 578 |

| Variable | Proportion/Mean (SD) | N |

|---|---|---|

| Focus group participants | 41 | |

| FG1 AIDS | 4 | |

| FG2 chronic pain | 7 | |

| FG3 colon cancer | 5 | |

| FG4 chronic ischemic heart disease | 4 | |

| FG5 rare chronic illnesses | 4 | |

| FG6 mixed group by survey institute | 8 | |

| FG7 mixed group by survey institute | 9 | |

| Age [min, max: 27–83] | 58.34 (14.83) | 38 |

| Gender | 41 | |

| male | 56.1 | 23 |

| female | 43.9 | 18 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gille, S.; Griese, L.; Schaeffer, D. Preferences and Experiences of People with Chronic Illness in Using Different Sources of Health Information: Results of a Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413185

Gille S, Griese L, Schaeffer D. Preferences and Experiences of People with Chronic Illness in Using Different Sources of Health Information: Results of a Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):13185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413185

Chicago/Turabian StyleGille, Svea, Lennert Griese, and Doris Schaeffer. 2021. "Preferences and Experiences of People with Chronic Illness in Using Different Sources of Health Information: Results of a Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 13185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413185

APA StyleGille, S., Griese, L., & Schaeffer, D. (2021). Preferences and Experiences of People with Chronic Illness in Using Different Sources of Health Information: Results of a Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413185