Point of Sale Advertising and Promotion of Cigarettes, Electronic Cigarettes, and Heated Tobacco Products in Warsaw, Poland—A Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

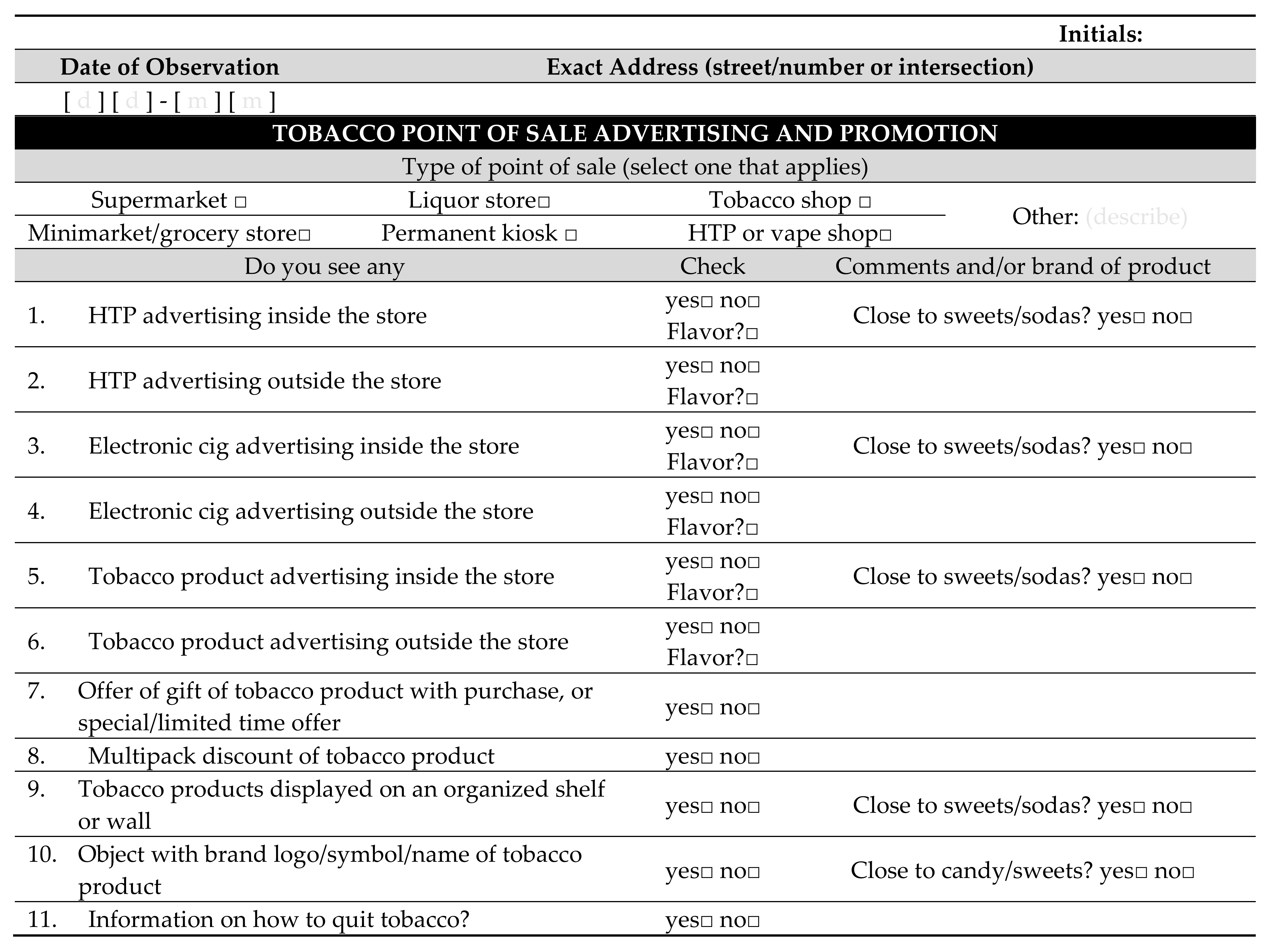

2. Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Several POS violate the law banning the advertisement and promotion of tobacco and nicotine consumer product in Poland. Efforts to enforce the law are suboptimal, and the governmental agencies responsible for enforcement should act swiftly.

- The display of tobacco products at POS is prevalent and should be explicitly banned in Poland. Other countries have shown the way and the benefits of doing so [35]. A recent evaluation of the legislation banning tobacco displays at POS in Scotland showed multiple benefits. Among other benefits, the ban was associated with reducing the risk of smoking initiation in young people and the perceived accessibility of tobacco.

- Further studies are needed on the advertisement and promotion strategies for nicotine products, particularly those addressed at young people. Field studies—similar to the one described in this article—can provide a real-time picture of the functioning of tobacco control laws, as well as any flaws and imperfections. The results will provide feedback for policymakers and stakeholders on what should be done in tobacco prevention, both in the short and long term. In our opinion, this pilot study should be continued in the future but in a broader form; for example, including rural areas, higher numbers of POS, and taking into account the identification of particular types of promotion and advertisement in the context of different variables such as types of POS and nicotine products.

- A final recommendation to protect children and teens from the harms of tobacco is to reduce the high density of tobacco and nicotine retailers. Our study indicates that the density of tobacco POS in Warsaw may exceed the POS densities in other European cities. There are four primary policy approaches to reducing tobacco POS density: (a) prohibiting sales in specific retailer types; (b) prohibiting sales near youth-populated areas, including schools; (c) “declustering” POS by requiring them to be at a minimum distance from each other; and (d) capping the number of tobacco POS to a certain amount within a community. All these approaches effectively reduce retailer density reduction but outlawing the sale of tobacco products within a certain radius from schools tends to gather the most support [36].

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health, Global Tobacco Surveillance System Data (GTSS Data). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/global/gtss/gtssdata/index.html (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- World Health Organization. Summary Results of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in Selected Countries of the WHO European Region; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336752/WHO-EURO-2020-1513-41263-56157-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Dąbrowska, K.; Sierosławski, J.; Wieczorek, L. Trends in tobacco-related behaviour among young people in Poland from 1995 to 2015 against a background of selected European countries. Alcohol. Drug Addict. 2018, 31, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balwicki, L.; Smith, D.; Balwicka-Szczyrba, M.; Gawron, M.; Sobczak, A.; Goniewicz, M.L. Youth Access to Electronic Cigarettes in an Unrestricted Market: A Cross-Sectional Study from Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lovato, C.; Watts, A.; Stead, L.F. Impact of Tobacco Advertising and Promotion on Increasing Adolescent Smoking Behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 2011, Cd003439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, S.; Davis, R.; Gilpin, E.; Loken, B.; Viswanath, K.; Wakefield, M. Influence of Tobacco Marketing on Smoking Behavior. Monograph 19: The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Tobacco Use, 1st ed.; National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2008. Available online: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-08/m19_complete.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General, 1st ed.; Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2016. Available online: https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/2016_SGR_Full_Report_non-508.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Lienemann, B.A.; Rose, S.W.; Unger, J.B.; Meissner, H.I.; Byron, M.J.; Baezconde-Garbanati, L.; Huang, L.L.; Cruz, T.B. Tobacco Advertisement Liking, Vulnerability Factors, and Tobacco Use among Young Adults. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Poland. Ustawa z Dnia 9 Listopada 1995, r. o Ochronie Zdrowia Przed Następstwami Używania Tytoniu i Wyrobów Tytoniowych; [Act of 9 November 1995 on Protection of Public Health against the Effects of Tobacco Use]. 1995. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19960100055/U/D19960055Lj.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Government of Poland. Ustawa z Dnia 5 Listopada 1999 r. o Zmianie Ustawy o Ochronie Zdrowia Przed Następstwami Używania Tytoniu i Wyrobów Tytoniowych; [Act of 5 November 1999 on Protection of Public Health againts the Effects of Tobacco Use]—Amendment to the Act. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19990961107/T/D19991107L.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- WHO. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2019: Offer Help to Quit Tobacco Use; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1239531/retrieve (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- WHO. Evidence Brief: Tobacco Point-of-Sale Display Bans, 1st ed.; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020; Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/339233/who-evidence-brief-pos-ban-eng.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Robertson, L.; McGee, R.; Marsh, L.; Hoek, J. A Systematic Review on the Impact of Point-of-Sale Tobacco Promotion on Smoking. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014, 17, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Robertson, L.; Cameron, C.; McGee, R.; Marsh, L.; Hoek, J. Point-of-Sale Tobacco Promotion and Youth Smoking: A Meta-Analysis. Tob. Control 2016, 25, e83–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. GYTS EURO 2016 Poland All Schools Weighted Percent Per Variable. CDC/WHO. 2016. Available online: https://nccd.cdc.gov/GTSSDataSurveyResources/Ancillary/DownloadAttachment.aspx?DatasetID=3318 (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- WHO. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2017: Monitoring Tobacco Use and Prevention Policies, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255874/1/9789241512824-eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Zegara, T.; Bieńkowska, M.; Błaszczak, E.; Cieciora, I.; Czyżkowska, A.; Kaźmierczak, E.; Kwiecień, T.; Kotowoda, J.; Pasterkowska, A.; Podolska, J.; et al. Panorama of Warsaw Districts in 2018, 1st ed.; Statistical Office in Warszawa: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. Available online: https://warszawa.stat.gov.pl/download/gfx/warszawa/pl/defaultaktualnosci/760/5/20/1/panorama_2018.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Wykaz Przedszkoli, Szkół i Placówek Oświatowych Prowadzonych Przez m.st. Warszawę w 2020 Roku. Biuro Edukacji Miasta Stołecznego Warszawy; [List of Kindergartens, Schools and Educational Institutions Run by the Capital City of Warsaw in 2020. Education Office of the Capital City of Warsaw]. Available online: https://edukacja.um.warszawa.pl/documents/66399/22588416/bip_edukacja_2019_2020.xls/971f9c32-4fd5-ccff-1935-f866072615aa?t=1634497645990 (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Pinkas, J.; Kaleta, D.; Zgliczyński, W.S.; Lusawa, A.; Wrześniewska-Wal, I.; Wierzba, W.; Gujski, M.; Jankowski, M. The Prevalence of Tobacco and E-Cigarette Use in Poland: A 2019 Nationwide Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Polanska, K.; Kaleta, D. Tobacco and E-Cigarettes Point of Sale Advertising-Assessing Compliance with Tobacco Advertising, Promotion and Sponsorship Bans in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazubski, B.M.; Durlik, J.; Balwicki, Ł.; Kaleta, D. Program Zwalczania Następstw Zdrowotnych Używania Wyrobów Tytoniowych i Wyrobów Powiązanych w Ramach Narodowego Programu Zdrowia. Ankietowe Badanie Młodzieży. Wrocław 2019; [Program of Combating the Health Consequences of Using Tobacco and Related Products under the National Health Program. A Youth Survey. Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego. Wroclaw 2019]. Available online: https://www.pzh.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/RAPORT-TYTO%C5%83-M%C5%81ODZIE%C5%BB-GRUDZIE%C5%83-2019-WERSJA-FINALNA-www.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Anastasopoulou, S. Market Report: Heated Tobacco Popularity Increases in Poland. Tobacco Intelligence, Tamarind Media Limited. 10 November 2020. Available online: https://tobaccointelligence.com/market-report-heated-tobacco-popularity-increases-in-poland/ (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Trząsalska, A.; Krassowska, U. Raport z Ogólnopolskiego Badania Ankietowego na Temat Postaw Wobec Palenia Tytoniu. Kantar dla Głównego Inspektoratu Sanitarnego. Warszawa, 2019; [Report from a Nationwide Survey on Attitudes towards Smoking. Kantar for the Chief Sanitary Inspectorate. Warsaw, 2019]; Chief Sanitary Inspectorate: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. Available online: https://gis.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Postawy-Polak%C3%B3w-do-palenia-tytoniu_Raport-Kantar-Public-dla-GIS_2019.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Nuyts, P.A.W.; Kuipers, M.A.G.; Cakir, A.; Willemsen, M.C.; Veldhuizen, E.M.; Kunst, A.E. Visibility of Tobacco Products and Advertisement at the Point of Sale: A Systematic Audit of Retailers in Amsterdam. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stead, M.; Eadie, D.; MacKintosh, A.M.; Best, C.; Miller, M.; Haseen, F.; Pearce, J.R.; Tisch, C.; Macdonald, L.; MacGregor, A.; et al. Young People’s Exposure to Point-of-Sale Tobacco Products and Promotions. Public Health 2016, 136, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Freeman, B.; Chapman, S. Evidence of the Impact of Tobacco Retail Policy Initiatives; New South Wales Government: St Leonards, NSW, Australia, 2014. Available online: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/tobacco/Documents/apdix-evidence-tob-retail-policy.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Marsh, L.; Vaneckova, P.; Robertson, L.; Johnson, T.O.; Doscher, C.; Raskind, I.G.; Schleicher, N.C.; Henriksen, L. Association Between Density and Proximity of Tobacco Retail Outlets with Smoking: A Systematic Review of Youth Studies. Health Place 2021, 67, 102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute for Global Tobacco Control. Technical Report on Tobacco Marketing at the Point-of-Sale in Five Slovenian Regions: Product Display, Advertising and Promotion around Schools; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.takeapart.org/tiny-targets//reports/Slovenia-Report.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Institute for Global Tobacco Control. Technical Report on Tobacco Marketing at the Point-of-Sale in Sarajevo and Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina: Product Display, Advertising and Promotion around Primary and Secondary Schools; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.takeapart.org/tiny-targets//reports/Bosnia-Herzegovina-Report.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Institute for Global Tobacco Control. Technical Report on Tobacco Marketing at the Point-of-Sale in Chisinau and Balti, Moldova: Product Display, Advertising, and Promotion around Primary and Secondary Schools; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.takeapart.org/tiny-targets//reports/Moldova-Report.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Institute for Global Tobacco Control. Technical Report on Tobacco Marketing at the Point-of-Sale in Kiev, Ukraine: Product Display, Advertising, and Promotion around Schools; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.takeapart.org/tiny-targets//reports/Ukraine-Report.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Institute for Global Tobacco Control. Technical Report on Tobacco Marketing at the Point-of-Sale in Bucharest, Romania: Product Display, Advertising, and Promotion around Primary and Secondary Schools; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.takeapart.org/tiny-targets//reports/Romania-Report.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Institute for Global Tobacco Control. Technical Report on Tobacco Marketing at the Point-of-Sale in the French-Speaking Region of Switzerland: Product Display, Advertising and Promotion around Primary and Secondary Schools; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.takeapart.org/tiny-targets//reports/Switzerland-Report.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Institute for Global Tobacco Control. Technical Report on Tobacco Marketing at the Point-of-Sale in Tbilisi, Georgia: Product Display, Advertising, and Promotion around Schools; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.takeapart.org/tiny-targets//reports/Georgia-Report.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Haw, S.; Currie, D.; Eadie, D.; Pearce, J.; MacGregor, A.; Stead, M.; Amos, A.; Best, C.; Wilson, M.; Cherrie, M.; et al. Public Health Research. In The Impact of the Point-of-Sale Tobacco Display Ban on Young People in Scotland: Before-and-After Study; NIHR Journals Library: Southampton, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glasser, A.M.; Roberts, M.E. Retailer Density Reduction Approaches to Tobacco Control: A Review. Health Place 2021, 67, 102342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of POS | Closed | Open | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Gas station | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.8 | 2 | 1.6 |

| Kiosk | 6 | 54.5 | 18 | 16.1 | 24 | 19.5 |

| Liquor store | 2 | 18.2 | 3 | 2.7 | 5 | 4.1 |

| Minimarket | 2 | 18.2 | 74 | 66.1 | 76 | 61.8 |

| Supermarket | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 8.9 | 10 | 8.1 |

| HTP/vape shop | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other * | 1 | 9.1 | 5 | 4.5 | 6 | 4.9 |

| Total | 11 | 100.0 | 112 | 100.0 | 123 | 100.0 |

| Type of Advertising or Promotion at Each POS | n | % of Open POS * |

|---|---|---|

| Advertising of cigarettes—inside | 25 | 22.3 |

| Advertising of cigarettes—outside | 0 | 0.0 |

| Advertising of e-cigarettes or e-liquids—inside | 22 | 19.6 |

| Advertising of e-cigarettes or e-liquids—outside | 0 | 0.0 |

| Advertising of HTP devices or their inserts—inside | 50 | 44.6 |

| Advertising of HTP devices or their inserts—outside | 0 | 0.0 |

| Gifts or discounts with purchase of cigarettes and other tobacco products | 2 | 1.8 |

| Display of cigarettes and other tobacco products | 91 | 81.2 |

| Display of cigarettes and other tobacco products near sweets or soda | 21 | 18.8 |

| Merchandising and objects with cigarette and other tobacco product brands available | 67 | 59.8 |

| Any advertising or promotion | 93 | 83.0 |

| Any advertising or promotion law violation | 85 | 75.9 |

| District | School Areas Surveyed | Open POS in the Surveyed Area | Total Area Surveyed (km2) | POS Density (POS/km2) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bielany | 5 | 17 | 0.41 | 41.5 |

| Mokotów | 5 | 43 | 1.92 | 22.4 |

| Śródmieście | 5 | 52 | 1.57 | 33.1 |

| Total | 15 | 118 | 3.9 | 30.3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koczkodaj, P.; Cuchi, P.; Ciuba, A.; Gliwska, E.; Peruga, A. Point of Sale Advertising and Promotion of Cigarettes, Electronic Cigarettes, and Heated Tobacco Products in Warsaw, Poland—A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413002

Koczkodaj P, Cuchi P, Ciuba A, Gliwska E, Peruga A. Point of Sale Advertising and Promotion of Cigarettes, Electronic Cigarettes, and Heated Tobacco Products in Warsaw, Poland—A Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):13002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413002

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoczkodaj, Paweł, Paloma Cuchi, Agata Ciuba, Elwira Gliwska, and Armando Peruga. 2021. "Point of Sale Advertising and Promotion of Cigarettes, Electronic Cigarettes, and Heated Tobacco Products in Warsaw, Poland—A Pilot Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 13002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413002

APA StyleKoczkodaj, P., Cuchi, P., Ciuba, A., Gliwska, E., & Peruga, A. (2021). Point of Sale Advertising and Promotion of Cigarettes, Electronic Cigarettes, and Heated Tobacco Products in Warsaw, Poland—A Pilot Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413002