Abstract

Caring for people with COVID-19 on the front line has psychological impacts for healthcare professionals. Despite the important psychological impacts of the pandemic on nurses, the qualitative evidence on this topic has not been synthesized. Our objective: To analyze and synthesize qualitative studies that investigate the perceptions of nurses about the psychological impacts of treating hospitalized people with COVID-19 on the front line. A systematic review of qualitative studies published in English or Spanish up to March 2021 was carried out in the following databases: The Cochrane Library, Medline (Pubmed), PsycINFO, Web of Science (WOS), Scopus, and CINHAL. The PRISMA statement and the Cochrane recommendations for qualitative evidence synthesis were followed. Results: The main psychological impacts of caring for people with COVID-19 perceived by nurses working on the front line were fear, anxiety, stress, social isolation, depressive symptoms, uncertainty, and frustration. The fear of infecting family members or being infected was the main repercussion perceived by the nurses. Other negative impacts that this review added and that nurses suffer as the COVID-19 pandemic progress were anger, obsessive thoughts, compulsivity, introversion, apprehension, impotence, alteration of space-time perception, somatization, and feeling of betrayal. Resilience was a coping tool used by nurses. Conclusions: Front line care for people with COVID-19 causes fear, anxiety, stress, social isolation, depressive symptoms, uncertainty, frustration, anger, obsessive thoughts, compulsivity, introversion, apprehension, impotence, alteration of space-time perception, somatization, and feeling of betrayal in nurses. It is necessary to provide front line nurses with the necessary support to reduce the psychological impact derived from caring for people with COVID-19, improve training programs for future pandemics, and analyze the long-term impacts.

1. Introduction

The first reported case of COVID-19 emerged in Wuhan, China in late 2019 [1]. The virus that causes this disease is SARS-Co-V2, from the family of coronaviruses that are the origin of the most virulent diseases in humans, along with MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) and SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) [2]. Since then, COVID-19 has spread throughout the world, reaching pandemic dimensions, and having serious health, economic, and social impacts. As of 17 September 2021, the number of infected people in the world was 219 million, and 4.55 million deaths have been reported from this disease [3].

The most common symptoms of COVID-19 are fever, dry cough, tiredness, loss of appetite, confusion, chest tightness or pain, and dyspnea. Complications of this disease that can lead to death include respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis and septic shock, thromboembolism, and multiple organ failure [3,4]. In addition, some of the people affected with COVID-19 continue to experience long-term respiratory and neurological symptoms or fatigue [3].

Since the start of the pandemic, nurses have been on the front line caring for people with COVID-19. Various quantitative and qualitative studies show the impact of working on the front line with people with COVID-19, highlighting the following psychological impacts: anxiety, stress, depression [5,6], post-traumatic stress syndrome, psychological distress, and mental exhaustion [7]. In addition, previous studies show that the risk of being infected, the fear of infecting [8], social stigma [9], the discomfort of working with personal protective equipment (PPE) [10], and social isolation or uncertainty [11] are associated with increased stress and anxiety in professionals working on the front line [5,12]. Impacts are aggravated when there is no adequate emotional support in the work environment, there are insufficient security measures, or there is no adequate institutional support [13].

On the other hand, certain studies have looked at factors that increase the risk of developing mental health problems among front line healthcare professionals. Thus, a study highlights the workload, having respiratory or digestive symptoms, having carried out specific diagnostic tests for COVID-19, such as CRP, overseeing a family member, having a negative coping style, or work exhaustion [14]. Other influencing factors also reported are a history of psychiatric illness, working on the front line, not having contracted the disease [15], having an underlying organic pathology, being a woman, expressing concern for the family, fear of infection, lack of PPE [16], or being a nurse [7,17]. Concerning this last factor, we know that nurses working on the front line are significantly more likely to experience anxiety symptoms than other healthcare professionals [18], higher levels of stress and subjective load [19], and higher scores on insomnia and distress scales [20].

Several studies analyze the psychological manifestations and perceptions of health professionals in the first line, but most are quantitative, without inquiring into perceptions, or do not distinguish between professional categories [12,21,22].

There are two previous qualitative systematic reviews published in 2020 that analyze the experiences of nurses working in hospital settings caring for people with COVID-19 [23,24], but none of them aim to analyze the psychological impacts on nurses. One of them includes studies since the beginning of the pandemic and of previous respiratory epidemics such as SARS, analyzing, among other categories, the psychological and emotional impact on front line nurses, but it does not exclusively analyze the COVID-19 pandemic, so it cannot be extrapolated to the current situation [23]. The second review’s aim was to analyze the barriers perceived by nurses to care for people with COVID-19, and it only includes articles published between January and August 2020, analyzing only the first part of the pandemic, highlighting among its findings the emotional and psychological stress experienced by front line nurses, in addition to analyzing other aspects such as limited information on COVID-19 and the lack of support from managers perceived by nurses [24].

A large part of the psychological impacts appears in the long term, so it is necessary to carry out a synthesis of the updated qualitative evidence that analyzes the perceptions of nurses about the psychological impacts of caring for people with COVID-19 in the front line, including studies that have analyzed long-term impacts and various waves of the pandemic. Key information is needed that will help provide a global vision of the problem and its evolution as the pandemic progresses and to develop support strategies for front line nurses facing these types of health emergencies.

This review is focused on the perceptions of front line nursing professionals, without including other professionals. Compared to previous reviews, studies that investigate the first, second, and subsequent waves are included, with which the impact in the medium and long term can be analyzed. In addition, this review focuses exclusively on analyzing the psychological impacts, without considering other aspects that affect the nursing care of people with COVID-19.

The objective of this qualitative systematic review is to analyze and synthesize qualitative studies that investigate the perceptions of nurses about the psychological impacts of treating hospitalized people with COVID-19 in the front line.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

A qualitative systematic review was carried out according to the Cochrane recommendations for the synthesis of qualitative evidence [25] and the PRISMA 2020 recommendations for systematic reviews [26]. The protocol of this review was registered in PROSPERO (279339).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria, Sources of Information, and Search Strategy

A systematic review of qualitative studies published in English or Spanish up to March 2021 was carried out in the following databases: The Cochrane Library, Medline (Pubmed), PsycINFO, Web of Science (WOS), Scopus, and CINHAL. A secondary search was also carried out through the references found in the included articles.

Table 1 shows the search strategy used in the different databases, which was adjusted according to the requirements of each database (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search strategy in the selected databases.

The search and selection process of the articles was carried out independently by two researchers according to the established inclusion and exclusion criteria, subsequently agreeing on the results. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer mediated. During this process, the following criteria were used. Inclusion criteria: (1) Qualitative studies that analyzed the perceptions of nurses about the psychological impacts of caring for people with COVID-19 in the front line. (2) Studies carried out in the hospital setting. (3) Studies published in English or Spanish published until March 2021. Exclusion criteria: (1) Systematic reviews. (2) Mixed designs if the qualitative data were not analyzed in a disaggregated way. (3) Studies conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic or looking at other pandemics. (4) Studies that analyzed the perceptions of front line professionals without carrying out a separate analysis by professional category. (5) Studies whose sample included nursing students.

2.3. Selection of Studies

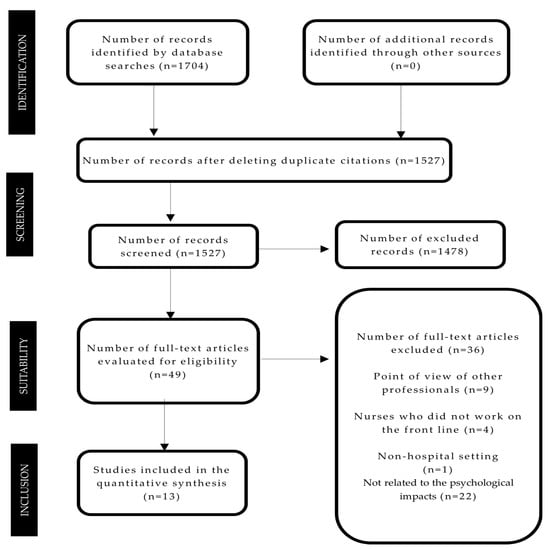

Screening of eligible studies was conducted in duplicate and independently by two reviewers following the established inclusion and exclusion criteria, in case of disagreement, a third reviewer was used. First, a search was carried out by the title and abstract After that, full-text articles were reviewed. The study selection was made following the flow chart of the study search and selection process that appears in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study search and selection process.

2.4. Data Extraction Process, Data List, and Summary Measures

The data were extracted independently by two researchers who subsequently agreed on the results, using an Excel template that included the data on the main characteristics of the analyzed studies, which are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the main characteristics of the analyzed studies.

2.5. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

The quality of the analyzed studies was assessed using the CASP tool for qualitative studies [40]. This tool was not used for inclusion or exclusion criteria, but rather to provide information on its methodological quality (Table 3).

Table 3.

Evaluation of the quality of the studies with the CASP tool for qualitative studies.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection Process

After searching the databases, 1704 articles were obtained from which duplicates were eliminated. After reading the title and abstract, 49 articles were reviewed in full text, of which 36 that did not meet the established criteria and were excluded. Thirteen articles were finally included in the qualitative synthesis upon meeting the selection criteria (Figure 1).

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Table 2 lists the main characteristics of the included studies. The results table collects the identified themes of each study related to the psychological impacts of caring people with COVID-19 expressed by the nurses. In the description of the results, the term “nurse” is used to refer to professionals of both genders as it is an internationally accepted term.

Concerning the paradigmatic approaches used in the analyzed studies, seven used content analysis [28,29,34,36,37,38,39], one the narrative analysis [32], three the phenomenological-descriptive approach [27,31,35], one the phenomenological-hermeneutic [30], and another the phenomenological approach without specifying the type [33]. In relation to data collection techniques, ten studies used semi-structured interviews [27,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39] and three used in-depth interviews [28,29,35].

All studies used intentional sampling. The total sample of the studies was 239 nurses, mostly women. The studies were conducted in Iran [27,28,29], Turkey [30,31], Canada [32], Italy [33], China [34,36,37,38], the United States of America [35], and Spain [39].

Regarding the length of time since exposure to front line work with COVID-19 patients, two of the articles did not specify when the data were collected or the exposure time [27,32]. In the rest, the exposure time ranged between one week [37] and three months [34]. In most articles, the data was collected between January and May 2020 [28,29,31,33,34,35,36,37,38,39], while in one article, the data was collected in June and August 2020 [30].

3.3. Synthesis of Results

The analyzed studies showed that front line care for people hospitalized with COVID-19 produces multiple and varied psychological impacts on nurses, without differences according to the exposure time in the analyzed articles. The psychological impacts most verbalized by the nurses were fear [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39], anxiety [27,28,29,30,31,34,38,39], stress [27,29,31,36,37,38], social isolation [31,32,35,36,38,39], depressive symptoms [31,38], uncertainty [32,33,36], anger [32,35], and frustration [32,34,39]. To a lesser extent, they also manifested the feeling of pressure [34], obsessive thoughts [28,31], introversion [31], apprehension [32], impotence [32], alteration of space-time perception [33], helplessness [34], somatization [38], feeling of betrayal [28], feeling overwhelmed [35], mental exhaustion [35], psychological pain [35], compulsivity [38], and sadness [32].

The main fears expressed by the nurses were infecting relatives or being infected [28,29,30,37,38], followed by the fear of death of the patients, both due to the high number of deaths and the conditions in which they occurred [29], fear of infection due to ignorance of the behavior of the virus [36], and the fear of death itself [27] or death of family members [27].

Anxiety also manifested itself in four subcategories: family separation anxiety (29), anxiety about the death of patients [28], anxiety about the nature of the illness [28], and anxiety before the burial of the corpses [28].

Resilience is understood as the ability to adapt flexibly to changes caused by stressful events and recover from negative emotional experiences and was considered by the nurses as the main coping technique to counteract the losses and traumas they experienced [32].

3.4. Analysis of the Quality of the Studies

The results of the quality analysis of the included studies were carried out with the CASP tool for qualitative studies and are shown in Table 3. All the articles fulfilled the items on the CASP tool, except for three articles that did not provide information about the relationship between researchers and participants [32,33,34] and another article that did not provide information about the rigor [28].

4. Discussion

This is the only qualitative systematic review to explore exclusively front line nurses’ perceptions about the psychological impacts of treating hospitalized people with COVID-19. None of the previous reviews exclusively analyze the psychological impacts on nurses working in hospital settings caring for people with COVID-19 [23,24]. A previous review includes articles from other respiratory epidemics [23] and the aim of another was to analyze the barriers perceived by nurses to care for people with COVID-19 [24]. The main psychological impacts of caring for people with COVID-19 perceived by nurses working on the front line were fear, anxiety, stress, social isolation, depressive symptoms, uncertainty, and frustration. The fear of infecting family members or being infected was the main repercussion perceived by the nurses.

It is known that the COVID-19 pandemic increases the level of anxiety and fear, stress, depression, frustration, and uncertainty among the general population [41,42]. In the case of nurses, the impacts are greater for caring on the front line, and new repercussions appear, which are explained below.

Fear, vulnerability, and psychological distress have been reported in a previous review as the main psychological consequences of front line care in other respiratory epidemics [23]. Our results follow the line of this review, showing that front line care during a pandemic leaves nurses feeling vulnerable, under pressure, stressed, and powerless. Moreover, our results show that nurses experienced loneliness and a high level of anxiety, more than that in the general population, due to concern for their health when caring for patients infected during these pandemics. The fear of infecting their family and friends is also common in nurses and in the general population [23,41,42] and is associated with an increased feeling of loneliness [23].

Furthermore, the results of this review are consistent with those of a previous review looking at studies conducted during the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic [24], showing that the main concern expressed by nurses working on the front line is transmitting the virus to their family members. In addition, our results also coincide with this review, contributing other psychological impacts of caring in the front line, such as feelings of anxiety, fear, overwhelm, mental exhaustion, depression, helplessness, and the social isolation experienced by nurses. Other psychological impacts perceived by nurses that do not appear in previous reviews [23,24] include anger, obsessive thoughts, compulsivity, introversion, apprehension, impotence, alteration of space-time perception, somatization, and feeling of betrayal.

The psychological impacts suffered by professionals working on the front line have been analyzed in multiple quantitative studies [7,11]. Our results are in line with those of a quantitative systematic review [43] which analyzes the psychological impacts of other pandemics and highlights that fear is considered by professionals as the main psychological manifestation along with anxiety and depression. In contrast, other quantitative reviews that analyze the first waves of the pandemic find that stress, anxiety, and depression are the main impacts of front line care [7,44]. These differences may be because this quantitative review analyzes the early psychological impacts of front line professionals, which can be sustained over time, while new symptoms appear as the pandemic evolves. As previously noted [45], the initial stress that professionals are subjected to in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic can evolve and manifest itself in different ways while healthcare personnel is exposed to this health emergency. Our findings follow this line, although more studies would be necessary to confirm whether these changes are maintained during the different stages of the pandemic.

The nurses in the studies included in this review considered that resilience helped counteract the losses and trauma they experience. According to a recent review, resilience can be improved by providing adequate information, psychosocial support, assigning tasks and responsibilities according to their intensity, and creating adequate working conditions [46].

Other studies suggest that improving the psychological assessment of professionals on an ongoing basis [47], improving work shifts and reducing workload [48], encouraging self-care [49], maintaining effective communication with workers, involving mental health professionals in supporting nurses, and ensuring the provision of personal protective equipment [50] are effective measures to reduce the psychological impact on front line health workers during the pandemic.

4.1. Implications for Clinical Practice

The results of this review show that it is necessary to monitor the psychological impacts in front line nurses [32], implement intervention strategies and psychological counseling [28,29,30,31,37], offer training programs that enable nurses to be better prepared [30], cope with the death of patients [28], and help nurses adapt to the sudden and extreme demands for future pandemics [27]. Providing nurses with enough personal protective material and adequate infrastructure and work environment is essential to reducing their fear [28,29,32]. Moreover, work should be organized based on individual roles and responsibilities [30], and the workforce should be reinforced to reduce workloads [32].

4.2. Limitations and Strengths

The limitations inherent to systematic reviews such as publication or selection bias should be considered. Furthermore, only including articles published in English or Spanish in the selected databases potentially left out relevant studies.

As a review of qualitative studies, this review provides richness in terms of the categories related to the main psychological manifestations. Future studies should include articles that analyze the long-term psychological impacts experienced by nurses in different waves to see if there are variations over time and include articles that analyze the point of view of nurses who work in different professional fields to find out if there are differences.

Future studies also need to investigate the most effective strategies to reduce the psychological impact on front line nurses to establish the appropriate measures from the onset of future pandemics.

5. Conclusions

The results of the study show that the main psychological impacts of caring for people with COVID-19 manifested by the nurses were fear, anxiety, stress, social isolation, depressive symptoms, uncertainty, and frustration. The fear of infecting family members or being infected was the main impact perceived by the nurses. As the pandemic progresses, fear prevails over stress, which was the main psychological impact in the initial phases of the pandemic. Moreover, other negative impacts that nurses suffer as the COVID-19 pandemic progress were anger, obsessive thoughts, compulsivity, introversion, apprehension, impotence, alteration of space-time perception, somatization, and feeling of betrayal. Resilience was considered as the main tool to face losses and trauma experienced by nurses. It is necessary to provide front line nurses with the necessary support to reduce the psychological impact derived from caring for people with COVID-19.

Author Contributions

Study design: D.S.-M., B.R.-M. and F.L.-E. data collection: S.H.-G., A.N. and P.Á.C.-A. data analysis: D.S.-M., B.R.-M., P.Á.C.-A. and F.L.-E. manuscript writing and revisions for important intellectual content: D.S.-M., B.R.-M., S.H.-G., A.N. and F.L.-E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

To Elena, Jaime, and Irene.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lin, Q.; Zhao, S.; Gao, D.; Lou, Y.; Yang, S.; Musa, S.S.; Wang, M.H.; Cai, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, L.; et al. A conceptual model for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in Wuhan, China with individual reaction and governmental action. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 93, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; De Clercq, E. Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) [Internet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Shrivastava, S.; Shrivastava, P. Minimizing the risk of international spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak by targeting travelers. J. Acute Dis. 2020, 9, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, J.; Petrey, J.; Huecker, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Worker Wellness: A Scoping Review. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, L.; Khalili, R.; Nir, M.S. Prevalence of Various Psychological Disorders during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Systematic Review. J. Mil. Med. 2020, 22, 648–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, K.; Singh, T.P.; Sharma, M.; Batra, R.; Schvaneveldt, N. Investigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 among healthcare workers: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashinyo, M.E.; Dubik, S.D.; Duti, V.; Amegah, K.E.; Ashinyo, A.; Larsen-Reindorf, R.; Akoriyea, S.K.; Kuma-Aboagye, P. Healthcare Workers Exposure Risk Assessment: A Survey among Frontline Workers in Designated COVID-19 Treatment Centers in Ghana. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaci, T.; Barattucci, M.; Ledda, C.; Rapisarda, V. Social Stigma during COVID-19 and its Impact on HCWs Outcomes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoernke, K.; Djellouli, N.; Andrews, L.; Lewis-Jackson, S.; Manby, L.; Martin, S.; Vanderslott, S.; Vindrola-Padros, C. Frontline healthcare workers’ experiences with personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: A rapid qualitative appraisal. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhai, T.; Yang, Q.; Yang, M.; Ning, Y.; et al. The Relationship Between Symptoms of Anxiety and Somatic Symptoms in Health Professionals During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 3153–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Falcó-Pegueroles, A.; Rosa, D.; Tolotti, A.; Graffigna, G.; Bonetti, L. The psychosocial impact of flu influenza pandemics on healthcare workers and lessons learnt for the COVID-19 emergency: A rapid review. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinaci, T.; Carpinelli, L.; Venuleo, C.; Savarese, G.; Cavallo, P. Emotional distress, psychosomatic symptoms and their relationship with institutional responses: A survey of Italian frontline medical staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Jin, Y.; He, M.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, X.; Song, S.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, X.; et al. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in healthcare workers deployed during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 56, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y.; Yong, Q.Y.J.O.; Chen, T.H.; Ho, S.H.C.; Chee, Y.I.C.; Chee, T.T. The Impact of COVID-19 on nurses working in a University Health System in Singapore: A qualitative descriptive study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kock, J.H.; Latham, H.A.; Leslie, S.J.; Grindle, M.; Munoz, S.-A.; Ellis, L.; Polson, R.; O’Malley, C.M. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: Implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erinoso, O.; Adejumo, O.; Fashina, A.; Falana, A.; Amure, M.T.; Okediran, O.J.; Abdur-Razzaq, H.; Anya, S.; Wright, K.O.; Ola, B. Effect of COVID-19 on mental health of frontline health workers in Nigeria: A preliminary cross-sectional study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 139, 110288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, P.; Devkota, N.; Dahal, M.; Paudel, K.; Joshi, D. Mental health impacts among health workers during COVID-19 in a low resource setting: A cross-sectional survey from Nepal. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, V.; Papazova, I.; Thoma, A.; Kunz, M.; Falkai, P.; Schneider-Axmann, T.; Hierundar, A.; Wagner, E.; Hasan, A. Subjective burden and perspectives of German healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 271, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.K.; Aker, S.; Şahin, G.; Karabekiroğlu, A. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, Distress and Insomnia and Related Factors in Healthcare Workers During COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheraton, M.; Deo, N.; Dutt, T.; Surani, S.; Hall-Flavin, D.; Kashyap, R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers globally: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 292, 113360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljeteig, I.; Forthun, I.; Hufthammer, K.O.; Engelund, I.E.; Schanche, E.; Schaufel, M.; Onarheim, K.H. Priority-setting dilemmas, moral distress and support experienced by nurses and physicians in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Nurs. Ethic 2021, 28, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.; Lord, H.; Halcomb, E.; Moxham, L.; Middleton, R.; Alananzeh, I.; Ellwood, L. Implications for COVID-19: A systematic review of nurses’ experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 111, 103637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.Y.; Liu, M.F. Nurses’ barriers to caring for patients with COVID-19: A qualitative systematic review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2021, 68, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, J.; Booth, A.; Cargo, M.; Flemming, K.; Harden, A.; Harris, J.; Garside, R.; Hannes, K.; Pantoja, T.; Thomas, J. Chapter 21: Qualitative evidence. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2019; pp. 525–545. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, Z.; Fereidouni, Z.; Behnammoghadam, M.; Alimohammadi, N.; Mousavizadeh, A.; Salehi, T.; Mirzaee, M.S.; Mirzaee, S. The Lived Experience of Nurses Caring for Patients with COVID-19 in Iran: A Phenomenological Study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galehdar, N.; Kamran, A.; Toulabi, T.; Heydari, H. Exploring nurses’ experiences of psychological distress during care of patients with COVID-19: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galehdar, N.; Toulabi, T.; Kamran, A.; Heydari, H. Exploring nurses’ perception of taking care of patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A qualitative study. Nurs. Open. 2020, 8, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muz, G.; Yüce, G.E. Experiences of nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 in Turkey: A phenomenological enquiry. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kackin, O.; Ciydem, E.; Aci, O.S.; Kutlu, F.Y. Experiences and psychosocial problems of nurses caring for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in Turkey: A qualitative study. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 67, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapum, J.; Nguyen, M.; Fredericks, S.; Lai, S.; McShane, J. “Goodbye … Through a Glass Door”: Emotional Experiences of Working in COVID-19 Acute Care Hospital Environments. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 53, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcadi, P.; Simonetti, V.; Ambrosca, R.; Cicolini, G.; Simeone, S.; Pucciarelli, G.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E.; Durante, A. Nursing during the COVID-19 outbreak: A phenomenological study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Yu, T.; Luo, K.; Teng, F.; Liu, Y.; Luo, J.; Hu, D. Experiences of clinical first-line nurses treating patients with COVID-19: A qualitative study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1381–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iheduru-Anderson, K. Reflections on the lived experience of working with limited personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 crisis. Nurs. Inq. 2021, 28, e12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, S.; Zhang, L.; Yan, H.; Shi, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chu, J. Experiences and psychological adjustments of nurses who voluntarily supported covid-19 patients in Hubei Province, China. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.E.; Zhai, Z.C.; Han, Y.H.; Liu, Y.L.; Liu, F.P.; Hu, D.Y. Experiences of front-line nurses combating coronavirus disease-2019 in China: A qualitative analysis. Public Health Nurs. 2020, 37, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, L.; Li, H.; Pan, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Wu, Q.; Wei, H. The Psychological Change Process of Frontline Nurses Caring for Patients with COVID-19 during Its Outbreak. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 41, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Castillo, R.; González-Caro, M.; Fernández-García, E.; Porcel-Gálvez, A.; Garnacho-Montero, J. Intensive care nurses’ experiences during the COVID -19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Nurs. Crit. Care 2021, 26, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Arana, A.; González Gil, T.; Cabello López, J.B. por CASPe. Plantilla para ayudarte a entender un artículo cualitativo. En: CASPe. Guias CASPe Lectura Circ. Lit. Med. 2010, 3, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, N.A.; Feroz, A.S.; Akber, N.; Feroz, R.; Meghani, S.N.; Saleem, S. When COVID-19 enters in a community setting: An exploratory qualitative study of community perspectives on COVID-19 affecting mental well-being. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e049851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafini, G.; Parmigiani, B.; Amerio, A.; Aguglia, A.; Sher, L.; Amore, M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. Qjm Int. J. Med. 2020, 113, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pablo, G.S.; Vaquerizo-Serrano, J.; Catalan, A.; Arango, C.; Moreno, C.; Ferre, F.; Shin, J.I.; Sullivan, S.; Brondino, N.; Solmi, M.; et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salari, N.; Khazaie, H.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Khaledi-Paveh, B.; Kazeminia, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Shohaimi, S.; Daneshkhah, A.; Eskandari, S. The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-regression. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Fernández, S.I.; Molina-Valdespino, D.; Ochoa-Palacios, R.; Sánchez-Guerrero, O.; Esquivel-Acevedo, J. Estrés, respuestas emocionales, factores de riesgo, psicopatología y manejo del personal de salud durante la pandemia por COVID-19. Acta Pediátr. Mex. 2020, 41, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckert, A.; Schuit, E.; Bleijenberg, N.; Cate, D.T.; De Lange, W.; Ginkel, J.M.D.M.-V.; Mathijssen, E.; Smit, L.C.; Stalpers, D.; Schoonhoven, L.; et al. How can we build and maintain the resilience of our health care professionals during COVID-19? Recommendations based on a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021, 11, e043718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.-Q.; Zhang, R.; Lu, Y.; Liu, H.; Kong, S.; Baker, J.S.; Zhang, H. Occupational stressors, mental health, and sleep difficulty among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating roles of cognitive fusion and cognitive reappraisal. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2021, 19, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Jiang, L.; Hu, Y.; Li, L.; Hou, L. Nurses’ experiences regarding shift patterns in isolation wards during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 4270–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callus, E.; Bassola, B.; Fiolo, V.; Bertoldo, E.G.; Pagliuca, S.; Lusignani, M. Stress Reduction Techniques for Health Care Providers Dealing with Severe Coronavirus Infections (SARS, MERS, and COVID-19): A Rapid Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 589698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sahoo, S. Pandemic and mental health of the front-line healthcare workers: A review and implications in the Indian context amidst COVID-19. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).