The Impact of a Peer Social Support Network from the Perspective of Women with Fibromyalgia: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Patient Recruitment and Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Empowerment

3.1.1. The SSN Facilitates Acceptance of the FM Diagnosis

“The group helped me understand and accept the diagnosis.” [P1—56 years old]

“What have I gained from the group? Well, understanding about this disease. What needs to be understood. That you’re not to blame.” [P1—56 years old]

“I got a lot out of it [the group], especially the fact that I now understand that not all FMs are the same. There are people who have FM who can still work, who lead a half-normal life, there are others who do not, that the FM poses obstacles [...]. Sometimes you know, you can’t cope, you’re sinking, but then you talk to them [the group] and you know it will pass, that this is how the disease is, and that better times are coming, and that helps you.” [P3—64 years old]

“I hadn’t told anyone because I thought it was something that I had to bear alone. But the group helped me understand the disease and what I had to say [to others], but as if it were a normal thing.” [P4—73 years old].

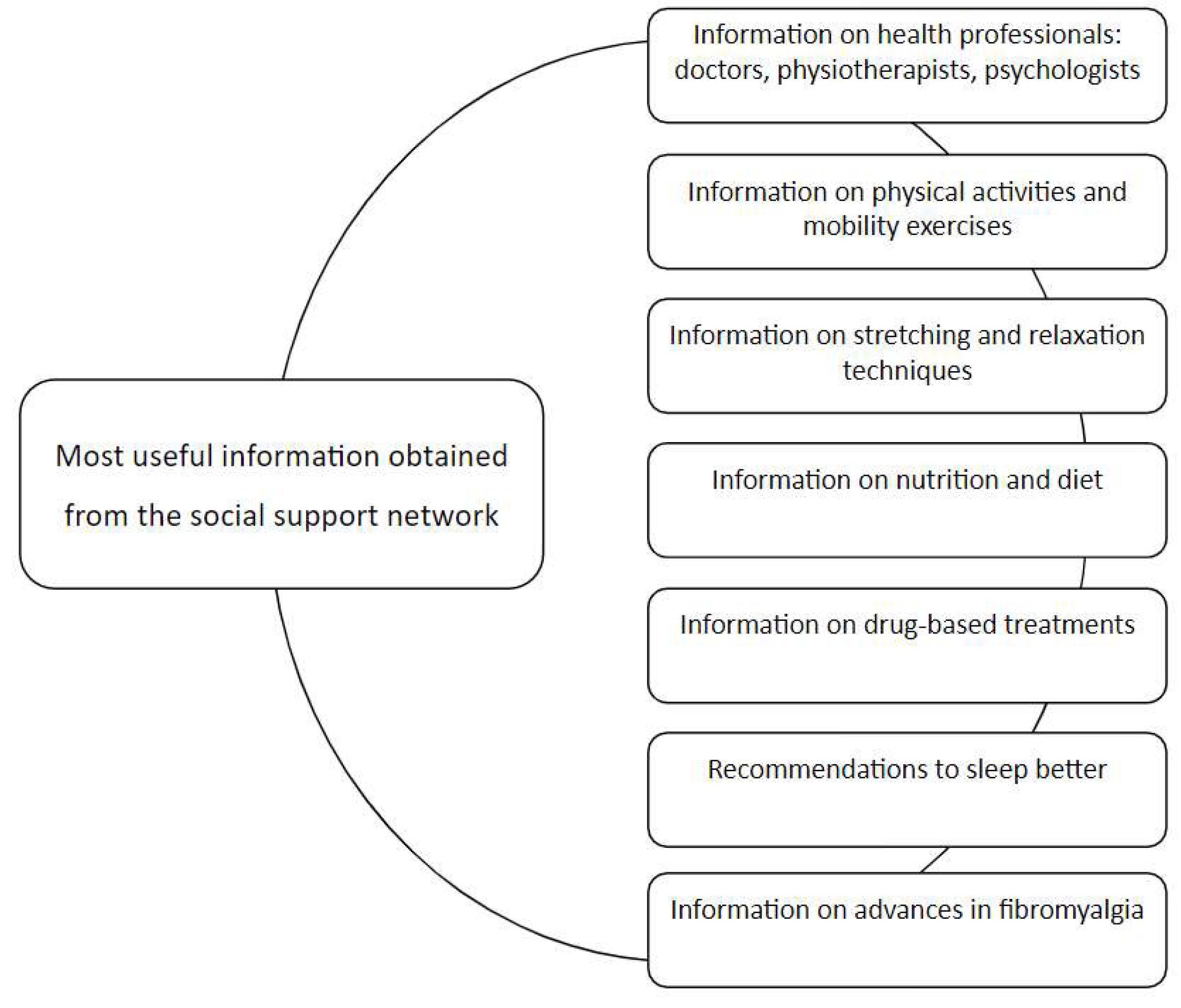

3.1.2. The SSN Is a Source of Information for Better FM Management

“Because they contribute things you might not have even thought about, and they make you think and see things differently” [P6—42 years old]

“I think the group is a positive thing, because when they [health professionals] diagnose you, they tell you what you have, but they don’t tell you what to do. They tell you to take painkillers when in pain, but they don’t tell you anything else. All this about food and relaxation has helped me a lot because the doctors don’t tell you anything.” [P4—73 years old]

“I’ve learned the gym exercises we need to do ... I’ve also made changes in my eating habits. I’m adding things I didn’t know before.” [P2—56 years old]

“What happens, though, is that sometimes we meet, and someone is very negative, that makes things go wrong.” [P1—56 years old]

3.2. Effects on Well-Being and QoL

3.2.1. The SSN Attenuates FM Stigma

“For whoever has one of these diseases it’s a stigma. I don’t want it to be known. I have it, the group knows, but that’s it. I wouldn’t like it to come out.” [P1—56 years old]

“For example, I didn’t tell my friends and family until a year and a half had gone by, ... because it was a time when it was said that FM is for people who have a bit of depression that they don’t know how to handle. I didn’t mention it, not even to my children.” [P4—73 years old]

“[They say] You’re making it ups, you’re lazy, you’re loafing, and that you don’t want to work, to do anything. And you feel very useless. And sometimes that’s what hurts you the most.” [P2—56 years old]

“It’s like emptying the backpack you’re carrying.” [P2—56 years old]

“I didn’t say anything because I thought it was something I had to go through and I shouldn’t say ... I didn’t want to complain! This [group] helped me to say it, but as something normal.” [P4—73 years old]

“The group has helped me to be more honest with myself. Not to hide the disease and not to think what others might say… it has helped me to be more myself, to trust more.” [P4—73 years old]

3.2.2. The SSN Improves Physical Well-Being by Helping with Symptom Control

“It hurts just the same, but your head is disconnected [from the pain]. And that moment of disconnection is very good for you.” [P1—56 years old]

“We talk a lot about the pain ... and then we send each other motivational words ... this encourages you and makes the pain less.” [P5—49 years old]

“Uf, you know that just speaking here, I feel better!” [P2—56 years old]

“When someone is very down … like, today I’m feeling really depressed ...well, we encourage each other, you know.” [P5—49 years old]

3.2.3. The SSN Provides Emotional Support and Bolsters Self-Esteem

“It helps me a lot ... emotionally, to be able to get support from people you know understand you.” [P5—49 years old]

“It’s very obvious that, for different reasons, some people do not have the support of their family and so they look for it in the group… they need this support.” [P3—64 years old]

“The group helped me, because of my age, I saw younger people ... I was managing well, but seeing young people with a lot of pain made me think.” [P4—73 years old]

“Some people are very down ...these we support privately.” [P1—56 years old]

“In the WhatsApp group we ask: So, how are you today? or, how are you not today?” [P1—56 years old]

“There were days when I couldn’t even get dressed, it was like there was a rage inside me ... It was typical to see people exercising there [in the group] ... and with their help I was more positive, seeing that there were things that I hadn’t even thought I could do.” [P6—42 years old]

“For example, when I explained relaxation techniques to them and saw that they wanted to know more ... I saw that what I was telling them was good for them.” [P2—56 years old]

3.2.4. The SSN Is a Socialization Medium

“There came a time when we began to meet up even after the group ended.” [P4—73 years old]

“It was great sharing the experiences of the week with other people ... How did the week go? How was your week? It was that, sharing your illness with other people ... In that sense, for me it was very positive, very, very much so.” [P3—64 years old]

“Before finding the group…. it happens that you feel very, very alone.” [P2—56 years old]

“Emotionally I don’t feel so alone […] The fact of sharing and having people who understand me makes me feel less alone.” [P5—49 years old]

“That helped me, to open up more… to the other people around me.” [P4—73 years old]

3.3. Valuable Aspects of the SSN

3.3.1. The SSN Transmits a Feeling of Being Understood

“The group helped me accept that there were things I couldn’t do, it helped me a little, no, a lot ... because I’ve always been very active and was always doing lots of things. And feeling limited or that there were days I couldn’t even get up, that was tough … it’s like, you know, this can’t be happening to me.” [P5—49 years old]

“Finding a group to share what I’m going through helped me a lot ... Before joining it, I found that many people do not understand FM [...], but here you find people that explain things and tell you things ... and it makes you feel really understood. You can share your pain or they share their pain; you understand them and they understand you [...]. You find that there are people who feel the same as you.” [P2—56 years old]

“I feel like I belong to a likeminded group of people.” [P2—56 years old]

3.3.2. The SSN Transmits a Feeling of Being Listened to

“We do a lot of psychology, which …. well, maybe I need it more than the others, or maybe not ... but you see people in great need, they are listened to and they feel understood.” [P6—42 years old]

3.3.3. The SSN Increases Personal Feelings of Satisfaction

“The talks we had (with a lot of positive emotions), the laughter … because it wasn’t just talk about FM, it was many things ... the truth is we had a great time.” [P3—64 years old]

“Well ... to say that it’s very positive, at least for me, who’s never been in any group ... It’s very positive .... I would 100% recommend we continue together, it’s great!” [P6—42 years old]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Sex | |

| Women | 6 (100%) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 57 (15.5) |

| Occupational status | |

| -Active employed | 3 (50%) |

| -Active unemployed | 2 (33.3%) |

| -Retired | 1 (16.7%) |

| Civil status | |

| -Married/partnered | 5 (83.3%) |

| -Divorced | 1 (16.7%) |

| Dependents/family burdens | |

| -Children | 6 (100%) |

| -Children living at home | 3 (50%) |

| -Other | 1 (16.7%) (care of grandchildren) |

| Time since fibromyalgia diagnosis | |

| P1_56 years old | 2 years |

| P2_56 years old | 12 years |

| P3_60 years old | 4 years |

| P4_73 years old | 5 years |

| P5_49 years old | 11 years |

| P6_42 years old | 10 years |

| TOPIC 1 Empowerment | TOPIC 2 Effects on Well-Being and Quality of Life | TOPIC 3 Valuable Aspects of the SSN | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATEGORIES CODES | The SSN facilitates acceptance of the FM diagnosis -acceptance -understanding -self-awareness The SSN is a source of information for better FM management -resolution of doubts -information -improved knowledge -better self-knowledge | The SSN attenuates FM stigma -understanding stigma -dealing with stigma The SSN improves physical well-being by helping control symptoms -pain management -pain control strategies -proactive care -improved habits -source of motivation The SSN provides emotional support and bolsters self-esteem -support -shared feelings -greater self-confidence -shared identity -disconnection -freedom to express myself -reduced guilt -improved self-esteem -better recognition as a person -encouragement -reduced anxiety -greater positivity -reduced frustration The SSN is a socialization medium -doubts -information -social contact | The SSN transmits a feeling of being understood -feeling understood -feeling that others understand -like-minded people -empathy The SSN transmits a feeling of being listened to -listened to -time for me -being able to talk openly The SSN increases personal feelings of satisfaction -greater well-being -feeling I belong -feeling I am useful |

References

- Wolfe, F.; Schmukler, J.; Jamal, S.; Castrejon, I.; Gibson, K.A.; Srinivasan, S.; Häuser, W.; Pincus, T. Diagnosis of Fibromyalgia: Disagreement between Fibromyalgia Criteria and Clinician-Based Fibromyalgia Diagnosis in a University Clinic. Arthritis Care Res. 2019, 71, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Jiménez, V.; Estévez-López, F.; Castro-Piñero, J.; Gallardo, I.C.A.; Soriano-Maldonado, A.; Borges-Cosic, M.; Delgado-Fernández, M. Association of Patterns of Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity Bouts With Pain, Physical Fatigue, and Disease Severity in Women With Fibromyalgia: The al-Ándalus Project. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoane-Mato, D.; Sánchez-Piedra, C.; Silva-Fernández, L.; Sivera, F.; Blanco, F.J.; Ruiz, F.P.; Juan-Mas, A.; Narváez, J.; Martí, N.Q.; Bustabad, S.; et al. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases in the adult population in Spain (EPISER 2016 study): Aims and methodology. Reumatol. Clínica 2019, 15, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, A.J.; Carmona, L.; Valverde, M.; Ribas, B. Prevalence and impact of fibromyalgia on function and quality of life in individuals from the general population: Results from a nationwide study in Spain. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2008, 26, 519–526. [Google Scholar]

- Revuelta Evrard, E.; Segura Escobar, E.; Paulino Tevar, J. Depresión, ansiedad y fibromialgia. Rev. Soc. Española Dolor 2010, 17, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.G.; França, M.H.; De Paiva, M.C.A.; Andrade, L.H.; Viana, M.C. Prevalence and clinical profile of chronic pain and its association with mental disorders. Rev. Saúde Pública 2017, 51, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgueiro, M.; García-Leiva, J.M.; Ballesteros, J.; Hidalgo, J.; Molina, R.; Calandre, E.P. Validation of a Spanish version of the Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, K.C.; Volcheck, M.M. Central Sensitization Syndrome and the Initial Evaluation of a Patient with Fibromyalgia: A Review. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2015, 6, e0020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, C.J. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011, 152, S2–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Häuser, W.; Katz, R.L.; Mease, P.J.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Walitt, B. 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin. Arthritis. Rheum. 2016, 46, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbunt, J.A.; Pernot, D.H.; Smeets, R.J. Disability and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2008, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Trabajo Migraciones y Seguridad Social. Guia de Actualización en la Valoración de Fibromialgia, Síndrome de fatiga Crónica, Sensibilidad Química Múltiple, Electrosensibilidad y Trastornos Somatomorfos, 2nd ed. Available online: http://www.seg-social.es/wps/wcm/connect/wss/6471dc88-9773-4cef-9605-31b3102c333e/GUIA+ACTUALIZACIÓN+FM%2C+SFC%2C+SSQM+y+ES.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID= (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Bernald, A.; Prince, A.; Edsall, P. Quality of life issues for fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Care Res. 2000, 13, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theadom, A.; Cropley, M.; Smith, H.E.; Feigin, V.L.; McPherson, K. Mind and body therapy for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD001980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musekamp, G.; Gerlich, C.; Ehlebracht-König, I.; Faller, H.; Reusch, A. Evaluation of a self-management patient education program for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: Study protocol of a cluster randomized controlled trial Rehabilitation, physical therapy and occupational health. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2016, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ríos, M.C.; Navarro-Ledesma, S.; Tapia-Haro, R.M.; Toledano-Moreno, S.; Casas-Barragán, A.; Correa-Rodríguez, M.; Aguilar-Ferrándiz, M.E. Effectiveness of health education in patients with fibromyalgia: A systematic review. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 55, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijs, J.; van Wilgen, C.P.; Van Oosterwijck, J.; van Ittersum, M.; Meeus, M. How to explain central sensitization to patients with ‘unexplained’ chronic musculoskeletal pain: Practice guidelines. Man. Ther. 2011, 16, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, N.A.C.G.; Berardinelli, L.M.M.; Sabóia, V.M.; Brito, I.d.S.; Santos, R.d.S. Interdisciplinary care praxis in groups of people living with fibromyalgia. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2016, 69, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yan, L.; Peng, J.; Tan, Y. Network Dynamics: How Can We Find Patients Like Us? Inf. Syst. Res. 2015, 26, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardinelli, L.M.M.; Guedes, N.A.C.; Ramos, J.P.; Nascimento, M.G. Tecnologia educacional como estratégia de empoderamento de pessoas com enfermidades crônicas. Rev. Enferm. UERJ 2015, 22, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Tan, Y. Feeling Blue? Go Online: An Empirical Study of Social Support Among Patients. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 690–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dambi, J.M.; Corten, L.; Chiwaridzo, M.; Jack, H.; Mlambo, T.; Jelsma, J. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the cross-cultural translations and adaptations of the Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (MSPSS). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psych. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Jin, X.-L.; Fang, Y. Moderating role of gender in the relationships between perceived benefits and satisfaction in social virtual world continuance. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 65, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowlton, A.R.; Hua, W.; Latkin, C. Social support networks and medical service use among HIV-positive injection drug users: Implications to intervention. AIDS Care 2005, 17, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechwald, W.A.; Prinstein, M. Beyond Homophily: A Decade of Advances in Understanding Peer Influence Processes. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011, 21, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, H. Knowledge sharing in online health communities: A social exchange theory perspective. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallinen, M.; Kukkurainen, M.L.; Peltokallio, L. Finally heard, believed and accepted—Peer support in the narratives of women with fibromyalgia. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 85, e126–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Uden-Kraan, C.F.; Drossaert, C.H.C.; Taal, E.; Shaw, B.R.; Seydel, E.R.; van de Laar, M.A.F.J. Empowering Processes and Outcomes of Participation in Online Support Groups for Patients With Breast Cancer, Arthritis, or Fibromyalgia. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, J.P.R.; Berardinelli, L.M.M.; Cavaliere, M.L.A.; Rosa, R.C.A.; Costa, L.P.D.; Barbosa, J.S.O. The routines of women with fibromyalgia and an interdisciplinary challenge to promote self-care. Rev. Gauch. Enferm. 2019, 40, e20180411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, P.; Larbig, W.; Braun, C.; Preissl, H.; Birbaumer, N. Influence of social support and emotional context on pain processing and magnetic brain responses in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50, 4035–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero-Molina, J.; Jiménez, T.M.M.; Rodríguez, C.R.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Castro-Sánchez, A.M.; Fernández-Sola, C. Social Support for Female Sexual Dysfunction in Fibromyalgia. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2016, 27, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R.; De Vault, M. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource, 4th ed.; Wiley Publications: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Caelli, K.; Ray, L.; Mill, J. ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2003, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlke, R.M. Generic Qualitative Approaches: Pitfalls and Benefits of Methodological Mixology. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2014, 13, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0761925415. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, R. Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2013, 15, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellawell, D. Inside–out: Analysis of the insider–outsider concept as a heuristic device to develop reflexivity in students doing qualitative research. Teach. High. Educ. 2006, 11, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, N.; Kaplan, C.; Ichesco, E.; Larkin, T.; Harris, R.E.; Murray, A.; Waiter, G.; Clauw, D.J. Neurobiologic Features of Fibromyalgia Are Also Present Among Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018, 70, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Undeland, M.; Malterud, K. The fibromyalgia diagnosis–Hardly helpful for the patients? A qualitative focus group study. Scand. J. Prim. Health Car 2007, 25, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, C.; Chouchou, F.; Dayot-Gorlero, J.; Zimmermann, P.; Maudoux, D.; Laurent, B.; Michael, G.A. Pain and emotion as predictive factors of interoception in fibromyalgia. J. Pain Res. 2018, 11, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armentor, J.L. Living with a contested, stigmatized illness: Experiences of managing relationships among women with fibromyalgia. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, M.; Ishikawa, H.; Kiuchi, T. Association of physicians’ illness perception of fibromyalgia with frustration and resistance to accepting patients: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2016, 35, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.T.; Swaminathan, A. Factors in the Building of Effective Patient-Provider Relationships in the Context of Fibromyalgia. Pain Med. 2019, 21, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juuso, P.; Söderberg, S.; Olsson, M.; Skär, L. The significance of FM associations for women with FM. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 1755–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arranz, L.-I.; Canela, M.-Á.; Rafecas, M. Dietary aspects in fibromyalgia patients: Results of a survey on food awareness, allergies, and nutritional supplementation. Rheumatol. Int. 2012, 32, 2615–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Dukes, E.M. The health status burden of people with fibromyalgia: A review of studies that assessed health status with the SF-36 or the SF-12. Int. J. Clin. Pr. 2007, 62, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, H.; Bockaert, M.; Bonte, J.; D’Haese, M.; Degrande, J.; Descamps, L.; Detaeye, U.; Goethals, W.; Janssens, J.; Matthys, K.; et al. The Impact of a Group-Based Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation Program on the Quality of Life in Patients with Fibromyalgia. JCR J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 26, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kool, M.B.; van de Schoot, R.; García, I.L.-C.; Mewes, R.; Silva, J.A.P.D.; Vangronsveld, K.; Wismeijer, A.A.J.; Lumley, M.A.; van Middendorp, H.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; et al. Measurement invariance of the Illness Invalidation Inventory (3*I) across language, rheumatic disease and gender. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, M.T.; Branscombe, N.R.; Postmes, T.; Garcia, A. The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 921–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Definition of Health—Public Health. Available online: https://www.publichealth.com.ng/world-health-organizationwho-definition-of-health/ (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Freitas, R.P.D.A.; de Andrade, S.C.; Spyrides, M.H.C.; Micussi, M.T.A.B.C.; de Sousa, M.B.C. Impacts of social support on symptoms in Brazilian women with fibromyalgia. Rev. Bras. Reum. 2017, 57, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Annemans, L.; Le Lay, K.; Taieb, C. Societal and Patient Burden of Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Pharmacoeconomics 2009, 27, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prins, J.; Huibers, M.; Servaes, P.; Van Der Werf, S.; Bos, E.; Van Der Meer, J.; Bleijenberg, G. Social Support and the Persistence of Complaints in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Psychother. Psychosom. 2004, 73, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, L.D.; Davis, M.C.; Yeung, E.W.; Tennen, H.A. The within-day relation between lonely episodes and subsequent clinical pain in individuals with fibromyalgia: Mediating role of pain cognitions. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 79, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuster, J.; McCormack, J.; Riddell, R.P.; Toplak, M.E. Understanding the Psychosocial Profile of Women with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Pain Res. Manag. 2009, 14, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodham, K.; Rance, N.; Blake, D. A qualitative exploration of carers’ and ‘patients’ experiences of fibromyalgia: One illness, different perspectives. Musculoskelet. Care 2010, 8, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnis, O.A.; McQuaid, R.J.; Bombay, A.; Matheson, K.; Anisman, H. Finding benefit in stressful uncertain circumstances: Relations to social support and stigma among women with unexplained illnesses. Stress 2015, 18, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurkkurainen, M.L. Fibromyalgia Patients´ Sense of Coherence, Social Support and Quality of Life. Ph.D Dissertation, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, S.; Gilbert, L. The role of ‘social support’ in the experience of fibromyalgia-narratives from South Africa. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Campayo, J.; Arnal, P.; Marqués, H.; Meseguer, E. Intervención psicoeducativa en pacientes con fibromialgia en atención primaria: Efectividad y diferencias entre terapia individual y grupal. Cuad. Med. Psicosomática 2005, 73, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rallo, A. Ruta Assistencial: Síndrome Sensibilitat Central. 2017. Available online: http://catsalut.gencat.cat/ca/coneix-catsalut/catsalut-territori/girona/publicacions/ (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Macfarlane, G.J.; Kronisch, C.; Dean, L.E.; Atzeni, F.; Häuser, W.; Fluß, E.; Choy, E.; Kosek, E.; Amris, K.; Branco, J.; et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. Chronic Pain (Primary and Secondary) in over 16s: Assessment of All Chronic Pain and Management of Chronic Primary Pain. 2021. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng193/chapter/Recommendations (accessed on 24 November 2021).

| 1. What has it meant to participate in a peer SSN? |

| 2. What changes has participation in a peer SSN brought about? |

| 3. What is the most valuable aspect of participating in a peer SSN? |

| 4. How could it be explained what it represents to participate in a peer SSN? |

| 5. Why would it be recommended to people with FM to participate in a peer SSN? |

| TOPIC 1 | TOPIC 2 | TOPIC 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empowerment | Effects on Well-Being and Quality of Life | Valuable Aspects of the SSN | |

| CATEGORIES | -The SSN facilitates acceptance of the FM diagnosis | -The SSN attenuates FM stigma | -The SSN transmits a feeling of being understood |

| -The SSN is a source of information for better FM management | -The SSN improves physical well-being by helping with symptom control | -The SSN transmits a feeling of being listened to | |

| -The SSN provides emotional support and bolsters self-esteem | -The SSN increases personal feelings of satisfaction | ||

| -The SSN is a socialization medium |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reig-Garcia, G.; Bosch-Farré, C.; Suñer-Soler, R.; Juvinyà-Canal, D.; Pla-Vila, N.; Noell-Boix, R.; Boix-Roqueta, E.; Mantas-Jiménez, S. The Impact of a Peer Social Support Network from the Perspective of Women with Fibromyalgia: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312801

Reig-Garcia G, Bosch-Farré C, Suñer-Soler R, Juvinyà-Canal D, Pla-Vila N, Noell-Boix R, Boix-Roqueta E, Mantas-Jiménez S. The Impact of a Peer Social Support Network from the Perspective of Women with Fibromyalgia: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312801

Chicago/Turabian StyleReig-Garcia, Glòria, Cristina Bosch-Farré, Rosa Suñer-Soler, Dolors Juvinyà-Canal, Núria Pla-Vila, Rosa Noell-Boix, Esther Boix-Roqueta, and Susana Mantas-Jiménez. 2021. "The Impact of a Peer Social Support Network from the Perspective of Women with Fibromyalgia: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312801

APA StyleReig-Garcia, G., Bosch-Farré, C., Suñer-Soler, R., Juvinyà-Canal, D., Pla-Vila, N., Noell-Boix, R., Boix-Roqueta, E., & Mantas-Jiménez, S. (2021). The Impact of a Peer Social Support Network from the Perspective of Women with Fibromyalgia: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12801. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312801