Examining Opportunities, Challenges and Quality of Life in International Retirement Migration

Abstract

:1. Introduction

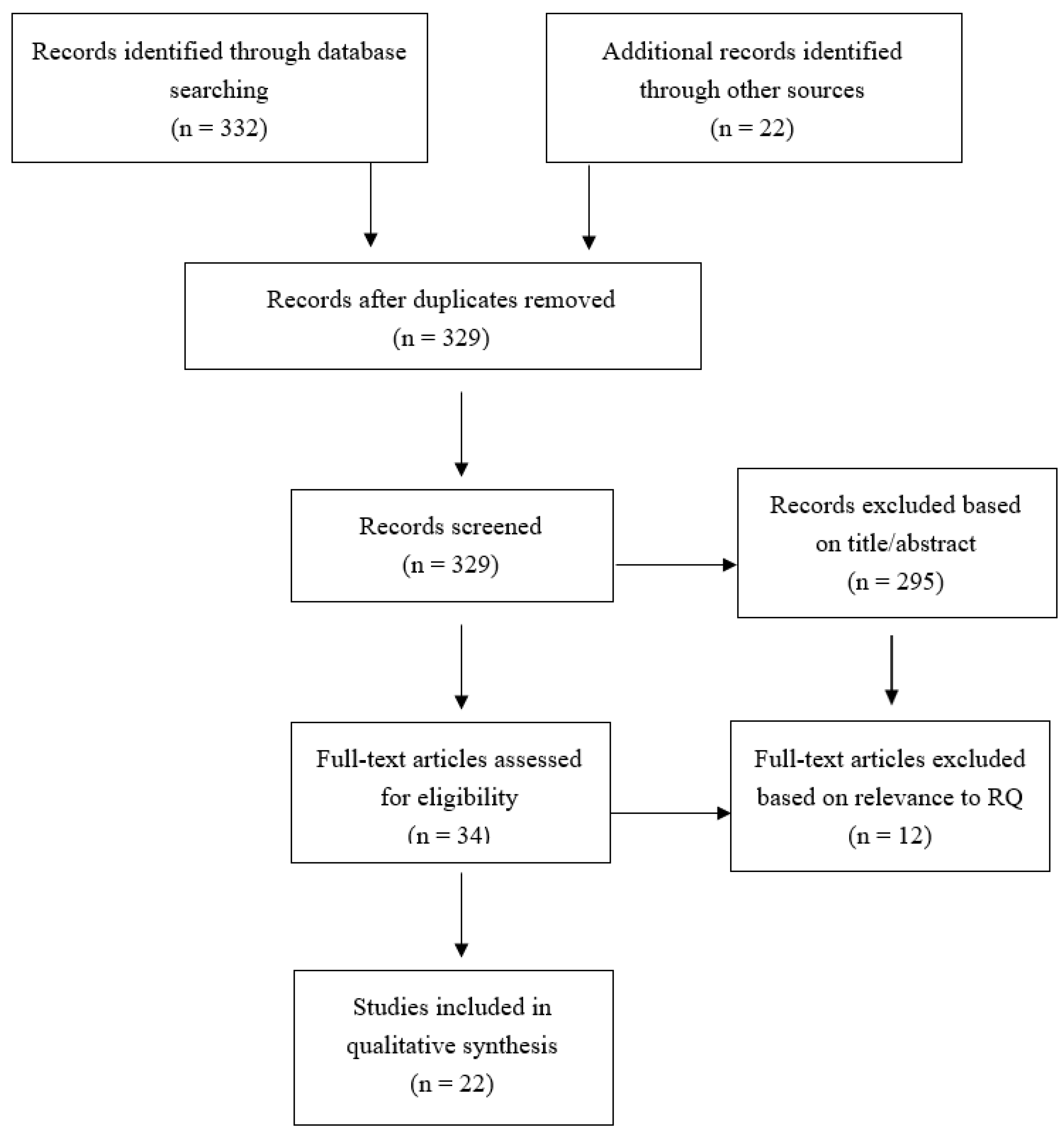

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Factors Associated with Retiring Abroad

2.2. Retirees’ Experiences with Retiring Abroad

2.3. Effects of International Retirement Migration

3. Discussion

3.1. Opportunities

3.2. Challenges

3.3. Recommendations for Research

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United States Census Bureau. Older People Projected to Outnumber Children for First Time in U.S. History. Available online: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/cb18-41-population-projections.html (accessed on 6 September 2018).

- Pew Research Center. Baby Boomers Retire. 2010. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2010/12/29/baby-boomers-retire/ (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Solinge, H.V.; Henkens, K. The meaning of retirement. How late career baby boomers envision their retirement. Innov. Aging 2018, 2 (Suppl. 1), 585. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6229146/ (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Gambold, L.L. DIY Aging: Retirement Migration as a New Age-Script. Anthropol. Aging 2018, 39, 82–93. Available online: http://anthro-age.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/anthro-age/article/view/175/223 (accessed on 17 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.I.; Martin, F. Humanistic psychology at the crossroads. In The Handbook of Humanistic Psychology: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd ed.; Schneider, K.J., Pierson, J.F., Bugental, J.F.T., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; Chapter 2; pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, D.; Hollstein, T.; Schweppe, C. The Emergence of care facilities in Thailand for older German-speaking people: Structural backgrounds and facility operators as transnational actors. Eur. J. Ageing 2017, 14, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyota, M.; Xiang, B. The emerging transnational “retirement industry” in Southeast Asia. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, A. International Retirement Migrants and Their Sense of Home: The Case of Malta; Oxford Books University: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Warnes, T. International retirement migration. In International Handbook of Population Aging; Uhlenberg, P., Ed.; Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4020-8356-3_15#citeas (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- The Council of Economic Advisers. 15 Economic Facts about Millennials. 2014. Available online: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/millennials_report.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Stončikaitė, I. Baby-boomers hitting the road: The paradoxes of the senior leisure tourism. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrow, H.B.; von Koppenfels, A.K. Modeling American migration aspirations: How capital, race, and national identity shape Americans’ ideas about living abroad. Int. Migr. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pickering, J.; Crooks, V.A.; Snyder, J.; Morgan, J. What is known about the factors motivating short-term international retirement migration? A scoping review. J. Popul. Ageing 2019, 12, 379–395. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12062-018-9221-y (accessed on 17 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Botterill, K. Discordant Lifestyle Mobilities in East Asia: Privilege and Precarity of British Retirement in Thailand. 2016. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/psp.2011 (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Gustafson, P.; Laksfoss Cardozo, A.E. Language use and social inclusion in international retirement migration. Soc. Incl. 2017, 5, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, V.; LeBlanc, H.P.; Sunil, T.S. US retirement migration to Mexico: Understanding issues of adaptation, networking, and social integration. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2014, 15, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.; Hardill, I. Retirement migration, the ‘other’ story: Caring for frail elderly British citizens in Spain. Ageing Soc. 2016, 36, 562–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hayes, M. The gringos of Cuenca: How retirement migrants perceive their impact on lower income communities. R. Geogr. Soc. 2018, 50, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, A. The Amenity Migrants of Cotacachi. Master’s Thesis, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2013. Available from Networked Digital Library of Theses & Dissertations. (Accession No osu1364551601). Available online: http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1364551601 (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Montanari, A.; Paluzzi, E. Human mobility and settlement patterns from eight EU countries to the Italian regions of Lombardy, Veneto, Tuscany, Lazio and Sicily. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2016, 65, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohno, A.; Farid, N.D.N.; Musa, G.; Aziz, N.A.; Nakayama, T.; Dahlui, M. Factors affecting Japanese retirees’ healthcare service utilisation in Malaysia: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010668. Available online: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/6/3/e010668 (accessed on 17 November 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohno, A.; Musa, G.; Farid, N.D.N.; Aziz, N.A.; Nakayama, T.; Dahlui, M. Issues in healthcare services in Malaysia as experienced by Japanese retirees. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 167. Available online: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-016-1417-3#article-info (accessed on 17 November 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Croucher, S. Privileged mobility in an age of globality. Societies 2012, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, M. We gained a lot over what we would have had: The geographic arbitrage of North American lifestyle migrants to Cuenca, Ecuador. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2014, 40, 1953–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M. Moving south: The economic motives and structural context of North America’s emigrants in Cuenca, Ecuador. Mobilities 2015, 10, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafran, A.; Monkkonen, P. Beyond Chapala and Cancún: Grappling with the impact of American migration to Mexico. Migr. Int. 2011, 6, 223–258. [Google Scholar]

- Croucher, S. The future of lifestyle migration: Challenges and opportunities. J. Lat. Am. Cult. Stud. 2015, 14, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, A. The impact of social security on return migration among Latin American elderly in the U.S. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2015, 34, 307–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.; Lee, J.; Gilligan, M. Resilience, adapting to change, and healthy aging. In Healthy Aging; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 329–334. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-06200-2_29#citeas (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Yamada, Y.; Merz, L.; Kisvetrova, H. Quality of life and comorbidity among older home care clients: Role of positive attitudes toward aging. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1661–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dua, P. A Biopsychosocial Approach to an Aging World. 2017. Available online: https://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/topss/2017-poorvi-dua.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Friedman, S.M.; Mulhausen, P.; Cleveland, M.L.; Coll, P.P.; Daniel, K.M.; Hayward, A.D.; Shah, K.; Skudlarska, B.; White, H.K. Healthy aging: American geriatrics society white paper executive summary. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hulla, R.; Brecht, D.; Stephens, J.; Salas, E.; Jones, C.; Gatchel, R. The biopsychosocial approach and considerations involved in chronic pain. Healthy Aging Res. 2019, 8, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siguaw, J.A.; Sheng, X.; Simpson, P.M. A biopsychosocial approach to an aging world. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2016, 85, 332–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stowe, J.D.; Cooney, T.M. Special issue: Successful aging—Examining Rowe and Kahn’s concept of successful aging: Importance of taking a life course perspective. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolnikov, T.R. Proposing a re-adapted successful aging model addressing chronic diseases in low-and middle-income countries. Qual. Life. Res. 2015, 24, 2945–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchard, J.; Villeda, S.A. Aging and brain rejuvenation as systemic events. J. Neurochem. 2015, 132, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carmona, J.S.; Michan, S. Biology of healthy aging and longevity. Rev. Investig. Clin. 2016, 68, 7–16. Available online: https://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/revinvcli/nn-2016/nn161b.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. Successful aging 2.0: Conceptual expansions for the 21st century. J. Gerontol. 2015, 70, 593–596. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/70/4/593/651547 (accessed on 17 November 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Steffens, N.K.; Jetten, J.; Haslam, C.; Cruwys, T.; Haslam, A. Multiple Social Identities Enhance Health Post-Retirement Because They Are a Basis for Giving Social Support. 2016. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01519/full (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Zontini, E. Growing old in a transnational social field: Belonging, mobility and identity among Italian migrants. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2015, 38, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. (n.d.). Mental Health by the Numbers. Available online: https://www.nami.org/learn-more/mental-health-by-the-numbers (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Charness, N.; Demiris, G.; Krupinski, E. Designing Telehealth for an Aging Population: A Human Factors Perspective; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gilleard, C.; Higgs, P. Aging without agency: Theorizing the fourth age. Aging Ment. Health. 2010, 14, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Source | Migration Flow | Article Type | Topic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | |||

| Bender, Horn and Schweppe, 2017 | Germans and Swiss | Thailand | Qualitative | Interview six old age care facilities |

| Benson and O’Reilly, 2018 | Global North Retirees | Malaysia and Panama | Theoretical | Impact of IRM to the receiving countries |

| Botterill, 2016 | Britain | Thailand | Qualitative | Interview 20 participants, between 50 to 70 years of age |

| Croucher, 2015 | Global North | Global South | Theoretical | Impact of IRM to the receiving countries |

| Gambold, 2018 | U.S | Mexico | Qualitative | Interview 78 participants between 2009–2010 and 2014–2015 |

| Britain | France and Spain | |||

| Gehring, 2019 | Dutch and Spanish | Dutch and Spanish | Qualitative | 86 interviews of Dutch and Spanish retirement migrants moving or returning to Spain and Dutch and Dutch-Turkish retirement migrants moving or returning to Turkey after retirement |

| Dutch-Turkish | Turkey | |||

| Gustafson and Cardozo, 2017 | Scandinavian | Spain | Qualitative | Interview 34 participants (14 Scandinavian retirees aged between 66 and 81 and 20 local residents) |

| Hall and Hardill, 2016 | Britain | Spain | Qualitative | Interview 9 males and 16 females, averaged age was 78.25 |

| Hamilton, 2015 | Europeans, Americans, and Maltese | Malta | Qualitative | Interview 7 participants (2 males and 5 females aged between 51 and 75) |

| Hayes, 2018 | N. Americans | Ecuador | Theoretical | Impact of IRM to the receiving countries |

| Horn and Schweppe, 2017 | Global North | Global South | Theoretical | Transnational aging |

| Kline, 2013 | Amenity migrants | Ecuador | Qualitative Thesis | Impact of IRM to the receiving countries |

| Kohno et al., 2016 | Japan | Malaysia | Qualitative | Interview 38 participants (30 Japanese, 16 males and 14 females, aged from 54 to 79 years and 8 medical services providers) |

| Lardiés-Bosque, 2016 | U.S. | Mexico | Qualitative | Interview 29 participants (15 males and 14 females, aged from 55 to 75 and older) |

| Marrow and von Koppenfels, 2018 | U.S. | Global South | Theoretical | Migration aspirations |

| Matarrita-Cascante et al., 2017 | Amenity/lifestyle migrants | Chile | Qualitative | Interview 46 participants (26 migrants and 22 local residents) |

| Miyashita et al., 2017 | Japan | Thailand | Qualitative | Interview 237 participants (mean age 68.8, with 79.3% of them being male) |

| Rojas et al., 2014 | U.S. | Mexico | Qualitative | Interview 375 participants (51.8 % of the subjects were male and 48.2% were female), averaged age was 68.05 years |

| Schafran and Monkkonen, 2011 | U.S. | Mexico | Theoretical | Impact of IRM to the receiving countries |

| Toyota and Xiang, 2012 | Japan | Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia | Theoretical | Interview 50 participants in Chiang Mai (Thailand), Penang (Malaysia), Cebu (the Philippines) and Bali (Indonesia) |

| Vega, 2015 | Latin American | Retirees return to their birth countries from the U.S. | Quantitative | Quantitative method using a 1% sample of the Social Security Administration’s Master Beneficiary Record (MBR) and the Numerical Identification System database (NUMIDENT) |

| Wong, Musa, and Taha, 2017 | European, American, Asian | Malaysia | Quantitative | Survey 504 participants (quantitative method, 64.3% of them aged 60 years and above) |

| Source | Pull Factors Associated with International Migration |

|---|---|

| Economic | Lower cost of living |

| Affordability of health care | |

| Affordability of housing | |

| Tax benefits | |

| Cheaper labor (domestic helping staff: maid, gardener, etc.) | |

| Investment opportunity (real estate, farming, retail business, etc.) | |

| Destination | Pleasant climate, beautiful natural and cultural environment |

| Urban amenities, such as advanced transportation infrastructures | |

| Easy access to recreation facilities for leisure, such as museums and parks | |

| Low crime rate | |

| Informal or relaxed lifestyle | |

| Same language spoken as the retired migrants’ country of origin | |

| Proximity to the retired migrants’ children and grandchildren, in order to be closer to family who may have already moved abroad | |

| People | Well-established expatriate communities with like-minded retirees |

| Friendly local residents | |

| Greater supply of skilled long-term care workers (e.g., Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines) | |

| Movement | Easy travel within the region (e.g., within EU countries, or between U.S. and Mexico) |

| Easy accessibility to friends and families in their country of origin, due to increased global mobility in the transportation sector | |

| Simple-to-obtain visa and residency status |

| Source | Push Factors Associated with International Migration |

|---|---|

| Socio/Cultural Adjustment | Inability to adapt to the different culture and inability to integrate into the local community |

| Different cultural expectations, and differences in understanding and mentality in care practice | |

| Lack of social support | |

| Host country was not what the retiree had expected it to be. | |

| Financial Factors | Global economic downturn, unavailable retirement benefits |

| Healthcare Benefit | Medicare and SSI coverage |

| Political Risk | Unexpected or uncertain political changes, such as Brexit |

| Healthcare Approaches | Differences in medical systems and healthcare services between retiree’s country of origin and the host country. For example, the medical systems and healthcare services in Malaysia differ from those in Japan. |

| Economic | Even though the migrants helped job creation and promoted economic growth in the receiving countries, the rising real estate prices due to the influx of migrants may have placed some locals at risk of being displaced due to lack of affordability. |

| Social | Migrants’ purchasing power gave them the opportunities to be landowners, business owners, or employers. The locals became the employees of the migrants. Therefore, social classes were created, based on social and economic status, which widened the inequality between the migrants and the locals. |

| Spatial | Migrants resided in gated communities or apartment condos while many locals who were employed by the migrants resided in the impoverished area, which was segregated from where the migrants resided. |

| Legal | The receiving countries facilitated visas application, provided tax advantages, and relaxed rules for owning land and establishing business for the migrants, while the locals may not have had the same tax advantages as the migrants; therefore, the locals may have been put at a disadvantage in business competition. |

| Environmental | Environmental degradation caused by the new real estate development resulted in pollution, especially near the coastal area. |

| Cultural | Migration ruined the authenticity of the destination locations, including some UNESCO World Heritage sites. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, Y.; Zolnikov, T.R. Examining Opportunities, Challenges and Quality of Life in International Retirement Migration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12093. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212093

Tang Y, Zolnikov TR. Examining Opportunities, Challenges and Quality of Life in International Retirement Migration. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):12093. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212093

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Yuan, and Tara Rava Zolnikov. 2021. "Examining Opportunities, Challenges and Quality of Life in International Retirement Migration" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22: 12093. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212093

APA StyleTang, Y., & Zolnikov, T. R. (2021). Examining Opportunities, Challenges and Quality of Life in International Retirement Migration. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12093. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212093