The Self-Absorptive Trait of Dissociative Experience and Problematic Internet Use: A National Birth Cohort Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

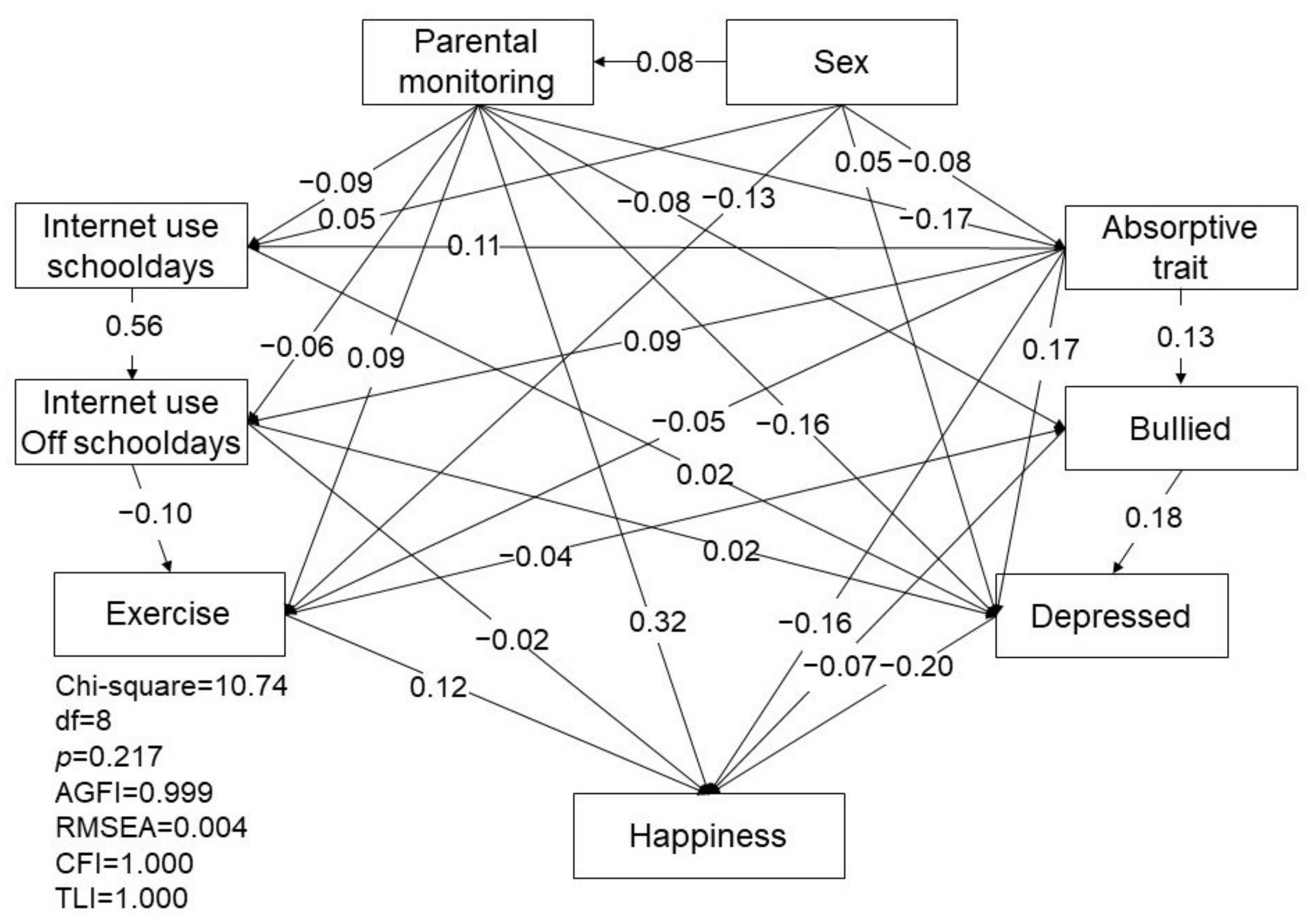

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Firth, J.; Torous, J.; Stubbs, B.; Firth, J.A.; Steiner, G.Z.; Smith, L.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M.; Gleeson, J.; Vancampfort, D.; Armitage, C.J.; et al. The “online brain”: How the Internet may be changing our cognition. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kurniasanti, S.; Assandi, P.; Ismail, R.I.; Nasrun, M.W.S.; Wiguna, T. Internet addiction: A new addiction? Med. J. Indones. 2019, 28, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, B.A.; Browne, D.; Tough, S.; Madigan, S. Trajectories of screen use during early childhood: Predictors and associated behavior and learning outcomes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 113, 106501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.J. Issues for DSM-V: Internet addiction. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehbein, F.; Kliem, S.; Baier, D.; Mößle, T.; Petry, N.M. Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in German adolescents: Diagnostic contribution of the nine DSM-5 criteria in a state-wide representative sample. Addiction 2015, 110, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korean National Information Society Agency. A Survey on Internet Addiction; Korean National Information Society Agency Report; Korean National Information Society Agency: Seoul, Korea, 2015.

- Young, K.S.; Rogers, R.C. The relationship between depression and internet addiction. Cyberspychol. Behav. 1998, 1, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Twenge, J.M.; Joiner, T.E.; Rogers, M.L.; Martin, G.N. Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 6, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dienlin, T.; Masur, P.K.; Trepte, S. Reinforcement or displacement? The reciprocity of FtF, IM, and SNS communication and their effects on loneliness and life satisfaction. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2017, 22, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaw, L.H.; Grant, L.M. In defense of the internet: The relationship between internet communication and depression, loneliness, self-esteem, and perceived social support. Cyberspychol. Behav. 2002, 5, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beran, T.; Li, Q. The relationship between cyberbullying and school bullying. J. Stud. Wellbeing 2007, 1, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Jian, S.Y.; Dong, M.; Gao, J.; Zhang, T.T.; Chen, X.Q.; Zhang, Y.F.; Shen, H.Y.; Cheng, H.R.; Gai, X.Y.; et al. Childhood trauma and suicidal ideation among Chinese university students: The mediating effect of Internet addiction and school bullying victimisation. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, E152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Wilson, A.; Cook, S.; Duan, Z.; Peng, K.; Hu, Z.; Ou, J.; Duan, S.; et al. The relationship between childhood trauma and Internet gaming disorder among college students: A structural equation model. J. Behav. Addict. 2020, 9, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schimmenti, A.; Caretti, V. Video-terminal dissociative trance: Toward a psychodynamic understanding of problematic internet use. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2017, 14, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- De Berardis, D.; D’Albenzio, A.; Gambi, F.; Sepede, G.; Valchera, A.; Conti, C.M.; Fulcheri, M.; Cavuto, M.; Ortolani, C.; Salerno, R.M.; et al. Alexithymia and its relationships with dissociative experiences and Internet addiction in a nonclinical sample. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffer-Dudek, N.; Shelef, L.; Oz, I.; Levkovsky, A.; Erlich, I.; Gordon, S. Absorbed in sleep: Dissociative absorption as a predictor of sleepiness following sleep deprivation in two high-functioning samples. Conscious Cogn. 2017, 48, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.K.; Roh, S.; Han, J.H.; Park, S.J.; Soh, M.A.; Han, D.H.; Shaffer, H.J. The relationship of problematic internet use with dissociation among South Korean internet users. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 241, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pasquale, C.; Sciacca, F.; Hichy, Z. Smartphone addiction and dissociative experience: An investigation in Italian adolescents aged between 14 and 19 years. Int. J. Psychol. Behav. Anal. 2015, 1, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, C.S.T.; Wong, H.T.; Yu, K.F.; Fok, K.W.; Yeung, S.M.; Lam, C.H.; Liu, K.M. Parenting approaches, family functionality, and internet addiction among Hong Kong adolescents. BMC Pediatr. 2016, 16, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shamus, E.; Cohen, G. Depressed, low self-esteem: What can exercise do for you? Internet J. Allied. Health Sci. Pract. 2009, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Associations of physical activity with sleep satisfaction, perceived stress, and problematic Internet use in Korean adolescents. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Derbyshire, K.L.; Lust, K.A.; Schreiber, L.R.N.; Odlaug, B.L.; Christenson, G.A.; Golden, D.J.; Grant, J.E. Problematic Internet use and associated risks in a college sample. Compr. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallgren, M.; Kraepelien, M.; Öjehagen, A.; Lindefors, N.; Zeebari, Z.; Kaldo, V.; Forsell, Y. Physical exercise and internet-based cognitive–behavioural therapy in the treatment of depression: Randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 207, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lung, F.W.; Shu, B.C.; Chiang, T.L.; Lin, S.L. Relationships between internet use, deliberate self-harm, and happiness in adolescents: A Taiwan birth cohort pilot study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.Y.; Lin, Y.H.; Lin, S.J.; Chiang, T.L. Cohort profile: Taiwan Birth Cohort Study (TBCS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 1430–1431i. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, F.W. Dissociation in Children and Adolescents: A Developmental Perspective; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lung, F.W.; Shu, B.C. The psychometric properties of the Chinese Oxford Happiness Questionnaire in Taiwanese adolescents: Taiwan Birth Cohort Study. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Stewart, S.M.; Byrne, B.M.; Wong, J.P.S.; Ho, S.Y.; Lee, P.W.H.; Lam, T.H. Factor structure of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale in Hong Kong adolescents. J. Pers. Assess. 2008, 2, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Li, A.Y. Internet addiction prevalence and quality of (real) life: A meta-analysis of 31 nations across seven world regions. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lung, F.W.; Shu, B.C.; Chiang, T.L.; Lin, S.J. Prevalence of bullying and perceived happiness in adolescents with learning disability, intellectual disability, ADHD and autism spectrum disorder: In the Taiwan Birth Cohort Pilot Study. Medicine 2019, 98, e14483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nansel, T.R.; Overpeck, M.; Pilla, R.S.; Ruan, W.J.; Simons-Morton, B.; Scheidt, P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA 2001, 285, 2094–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, L.T.; Peng, Z.W.; Mai, J.C.; Jing, J. Factors associated with Internet addiction among adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerniglia, L.; Zoratto, F.; Cimino, S.; Laviola, G.; Ammaniti, M.; Adriani, W. Internet addiction in adolescence: Neurobiological, psychosocial and clinical issues. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 76, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.S. The evolution of internet addiction. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 229–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, H.J.; Kwon, J.H. Risk and protective factors of internet addiction: A meta-analysis of empirical studies in Korea. Yonsei. Med. J. 2014, 55, 1691–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Floros, G.; Siomos, K. The relationship between optimal parenting, Internet addiction and motives for social networking in adolescence. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 209, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, P.; Plant, M. Parental guidance about drinking: Relationship with teenage psychoactive substance use. J. Adolesc. 2010, 33, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocentini, A.; Fiorentini, G.; Di Paola, L.; Menesini, E. Parents, family characteristics and bullying behavior: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 45, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, J.Y.; Yen, C.F.; Chen, C.C.; Chen, S.H.; Ko, C.H. Family factors of internet addiction and substance use experience in Taiwanese adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2007, 10, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.H.; Lin, S.L.; Wu, C.P. The effects of parental monitoring and leisure boredom on adolescents’ Internet addiction. Adolescence 2009, 44, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Young, K.S.; Cristiano, N.D.A. Internet Addiction in Children and Adolescents: Risk Factors, Assessment, and Treatment; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. Exercise rehabilitation for smartphone addiction. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2013, 9, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Child sex | |

| Boy | 9246 (52.3) |

| Girl | 8448 (47.7) |

| Have been bullied | |

| Always | 171 (1.0) |

| Often | 217 (1.2) |

| Sometimes | 818 (4.6) |

| Once in a while | 3087 (17.4) |

| Never | 13,401 (75.7) |

| Online time on school days | |

| ≤1 h | 11,295 (63.8) |

| ≥5 h | 943 (5.3) |

| Online time on off school days | |

| ≤1 h | 5416 (30.6) |

| ≥5 h | 4576 (25.9) |

| Exercise regularly | 14,518 (82.1) |

| Maternal education | |

| Illiterate | 13 (0.1) |

| Elementary school | 509 (2.9) |

| Middle school | 1433 (8.1) |

| High school | 6322 (35.7) |

| University/college | 8391 (47.4) |

| Graduate school | 1026 (5.8) |

| Paternal education: | |

| Illiterate | 5 (0.0) |

| Elementary school | 214 (1.2) |

| Middle school | 1788 (10.1) |

| High school | 6349 (35.9) |

| University/college | 7473 (42.2) |

| Graduate school | 1865 (10.5) |

| Variable (range) | Mean (SD) |

| Hours spend online | |

| School days | 1.55 (1.87) |

| Days without school | 3.62 (3.38) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lung, F.-W.; Shu, B.-C. The Self-Absorptive Trait of Dissociative Experience and Problematic Internet Use: A National Birth Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211848

Lung F-W, Shu B-C. The Self-Absorptive Trait of Dissociative Experience and Problematic Internet Use: A National Birth Cohort Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):11848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211848

Chicago/Turabian StyleLung, For-Wey, and Bih-Ching Shu. 2021. "The Self-Absorptive Trait of Dissociative Experience and Problematic Internet Use: A National Birth Cohort Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22: 11848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211848

APA StyleLung, F.-W., & Shu, B.-C. (2021). The Self-Absorptive Trait of Dissociative Experience and Problematic Internet Use: A National Birth Cohort Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211848