Differential Effects of Multiple Dimensions of Poverty on Child Behavioral Problems: Results from the A-CHILD Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

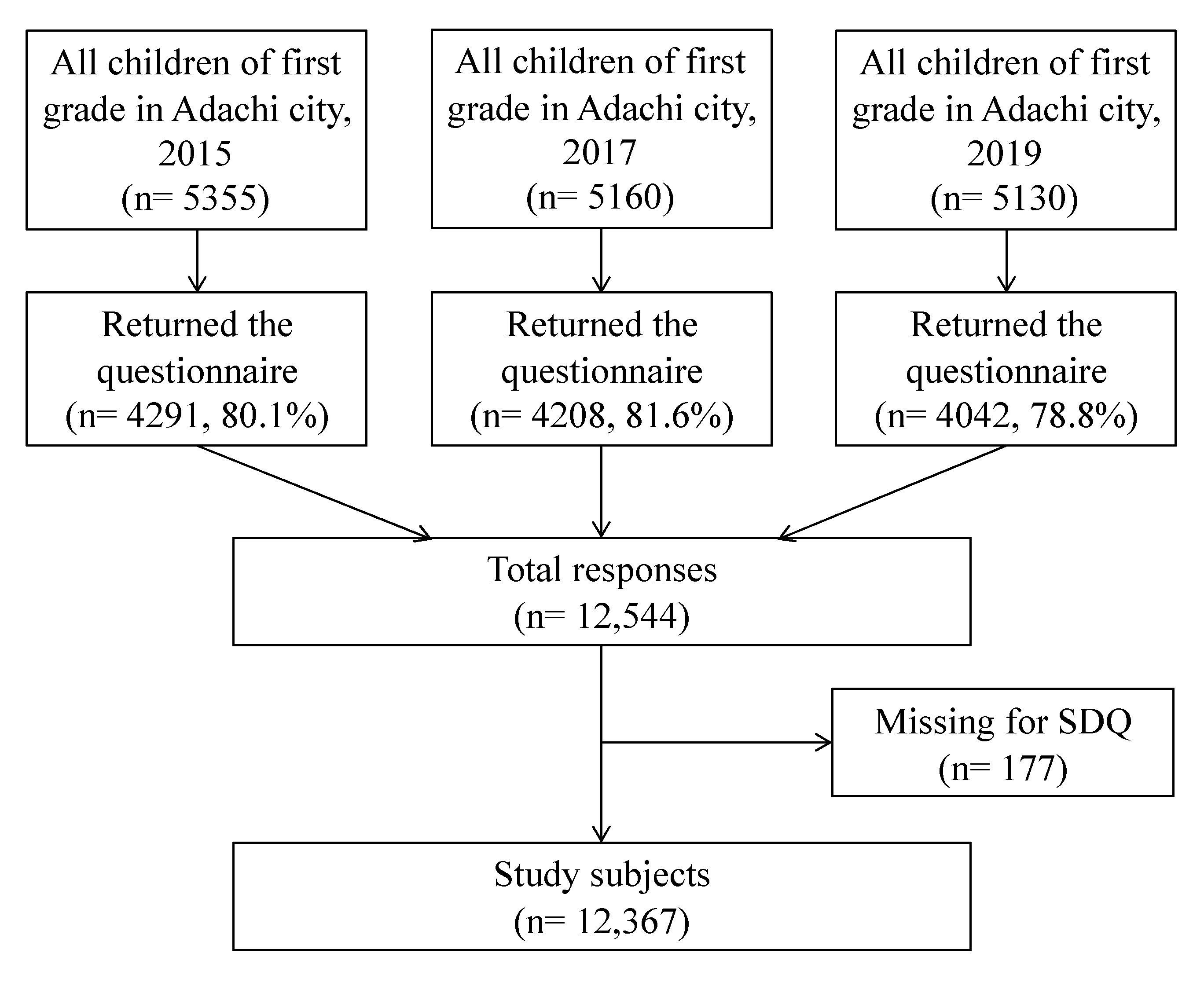

2.1. Study Samples

2.2. Low Income and Material Deprivation

2.3. Child Behavioral Problems

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of Multidimensional Poverty

4.2. Direct Effects of Life-Related and Child-Related Deprivation

4.3. Mediating Effects of Parental Psychological Distress and Social Support

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yoshikawa, H.; Aber, J.L.; Beardslee, W.R. The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of chil-dren and youth: Implications for prevention. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and Child Health in the United States. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20160339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blair, C.; Raver, C.C. Poverty, Stress, and Brain Development: New Directions for Prevention and Intervention. Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16 (Suppl. 3), S30–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnson, S.B.; Riis, J.L.; Noble, K. State of the Art Review: Poverty and the Developing Brain. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, N.L.; Hanson, J.; Wolfe, B.; Pollak, S.D. Association of Child Poverty, Brain Development, and Academic Achievement. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.; Leavy, J.; Masters, A. Comparative Perspectives on Child Poverty: A review of poverty measures. J. Hum. Dev. 2003, 4, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willitts, M. Measuring Child Poverty Using Material Deprivation: Possible Approaches; Department for Work and Pensions under licence from the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office by Corporate Document Services: Leeds, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff, E.T.; Aber, J.L.; Raver, C.C.; Lennon, M.C. Income is not enough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parent-ing and child development. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zilanawala, A.; Pilkauskas, N.V. Material hardship and child socioemotional behaviors: Differences by types of hardship, timing, and duration. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schenck-Fontaine, A.; Panico, L. Many Kinds of Poverty: Three Dimensions of Economic Hardship, Their Combinations, and Children’s Behavior Problems. Demography 2019, 56, 2279–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirby, N.; Wright, B.; Allgar, V. Child mental health and resilience in the context of socioeconomic disadvantage: Results from the Born in Bradford cohort study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bradshaw, J.; Finch, N. Overlaps in Dimensions of Poverty. J. Soc. Policy 2003, 32, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Conger, R.D.; Donnellan, M.B. An Interactionist Perspective on the Socioeconomic Context of Human Development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chzhen, Y.; Bruckauf, Z.; Toczydlowska, E. Sustainable Development Goal 1.2: Multidimensional Child Poverty in the European Union. 2017. Available online: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/894-sustainable-development-goal-12-multidimensional-child-poverty-in-the-european-union.html (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Yeung, W.J.; Linver, M.R.; Brooks-Gunn, J. How Money Matters for Young Children’s Development: Parental Investment and Family Processes. Child Dev. 2002, 73, 1861–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conger, R.D.; Ge, X.; Elder, G.H.; O Lorenz, F.; Simons, R.L. Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhnke, P. Are the poor socially integrated? The link between poverty and social support in different welfare regimes. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2008, 18, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigges, L.M.; Browne, I.; Green, G.P. Social Isolation of the Urban Poor: Race, Class, and Neighborhood Effects on Social Resources. Sociol. Q. 1998, 39, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhard, J. Does Poverty Increase the Risk of Social Isolation? Insights Based on Panel Data from Germany. Sociol. Q. 2018, 59, 338–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eijk, G. Does living in a poor neighbourhood result in network poverty? A study on local networks, locality-based relationships and neighbourhood settings. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2010, 25, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mulia, N.; Schmidt, L.; Bond, J.; Jacobs, L.; Korcha, R. Stress, social support and problem drinking among women in poverty. Addiction 2008, 103, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunes, C.; Martins, C.; Ayala-Nunes, L.; Matos, F.; Costa, E.; Gonçalves, A. Parents’ perceived social support and children’s psychological adjustment. J. Soc. Work 2020, 21, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, M.; Fujiwara, T. Association Between Parental Social Interaction and Behavior Problems in Offspring: A Population-Based Study in Japan. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2016, 23, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochi, M.; Isumi, A.; Kato, T.; Doi, S.; Fujiwara, T. Adachi Child Health Impact of Living Difficulty (A-CHILD) Study: Research Protocol and Profiles of Participants. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 31, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moriwaki, A.; Kamio, Y. Normative data and psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire among Japanese school-aged children. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2014, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sakurai, K.; Nishi, A.; Kondo, K.; Yanagida, K.; Kawakami, N. Screening performance of K6/K10 and other screening instruments for mood and anxiety disorders in Japan. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 65, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naven, L.; Egan, J.; Sosu, E.M.; Spencer, S. The influence of poverty on children’s school experiences: Pupils’ perspectives. J. Poverty Soc. Justice 2019, 27, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Family Database, CO2.2: Child Poverty. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/els/CO_2_2_Child_Poverty.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Malti, T.; Dys, S.P. From being nice to being kind: Development of prosocial behaviors. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 20, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandy, R.; Ottoni-Wilhelm, M. Family structure and income during the stages of childhood and subsequent prosocial behavior in young adulthood. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lichter, D.; Shanahan, M.; Gardner, E. Helping Others? The Effects of Childhood Poverty and Family Instability on Prosocial Behavior. Youth Soc. 2002, 34, 89–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.L. Empathy and Moral Development: Implications for Caring and Justice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Kalil, A.; Leininger, L. Low-income mothers’ private safety nets and children’s socioemotional well-being. J. Marriage Fam. 2009, 71, 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, G.; Bradshaw, J. A Child Material Deprivation Index. Child Indic. Res. 2012, 5, 503–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | 2015 | 2017 | 2019 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 12,367) | (n = 4219) | (n = 4168) | (n = 3980) | ||||||

| Mean/N | S.D./% | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | ||

| Child age | (Months old) | 84.7 | 3.5 | 85.2 | 3.56 | 84.5 | 3.42 | 84.4 | 3.52 |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Child sex | Female | 6073 | 49.1% | 2048 | 48.5% | 2055 | 49.3% | 1970 | 49.5% |

| Male | 6286 | 50.8% | 2166 | 51.3% | 2110 | 50.6% | 2010 | 50.5% | |

| Missing | 8 | 0.1% | 5 | 0.1% | 3 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Number of parents living at home | Two parents | 11,144 | 90.1% | 3785 | 89.7% | 3765 | 90.3% | 3594 | 90.3% |

| One parent | 1114 | 9.0% | 393 | 9.3% | 370 | 8.9% | 351 | 8.8% | |

| No parents | 109 | 0.9% | 41 | 1.0% | 33 | 0.8% | 35 | 0.9% | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Number of grandparents living at home | No grandparents | 11,127 | 90.0% | 3765 | 89.2% | 3758 | 90.2% | 3604 | 90.6% |

| One grandparent | 677 | 5.5% | 265 | 6.3% | 227 | 5.4% | 185 | 4.6% | |

| Two+ grandparents | 563 | 4.6% | 189 | 4.5% | 183 | 4.4% | 191 | 4.8% | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Number of children in the household | One child | 2539 | 20.5% | 871 | 20.6% | 854 | 20.5% | 814 | 20.5% |

| Two children | 6351 | 51.4% | 2167 | 51.4% | 2107 | 50.6% | 2077 | 52.2% | |

| Three children | 2797 | 22.6% | 948 | 22.5% | 974 | 23.4% | 875 | 22.0% | |

| Four+ | 676 | 5.5% | 229 | 5.4% | 233 | 5.6% | 214 | 5.4% | |

| Missing | 4 | 0.0% | 4 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Maternal age | <30 | 661 | 5.3% | 218 | 5.2% | 244 | 5.9% | 199 | 5.0% |

| 30–34 | 2231 | 18.0% | 756 | 17.9% | 753 | 18.1% | 722 | 18.1% | |

| 35–39 | 4104 | 33.2% | 1444 | 34.2% | 1372 | 32.9% | 1288 | 32.4% | |

| 40–44 | 3765 | 30.4% | 1301 | 30.8% | 1277 | 30.6% | 1187 | 29.8% | |

| 45+ | 1314 | 10.6% | 411 | 9.7% | 425 | 10.2% | 478 | 12.0% | |

| Missing | 292 | 2.4% | 89 | 2.1% | 97 | 2.3% | 106 | 2.7% | |

| Maternal education | High school | 4064 | 32.9% | 1507 | 35.7% | 1361 | 32.7% | 1196 | 30.1% |

| Technical school/junior college | 4922 | 39.8% | 1750 | 41.5% | 1673 | 40.1% | 1499 | 37.7% | |

| University | 3017 | 24.4% | 862 | 20.4% | 999 | 24.0% | 1156 | 29.0% | |

| Other/unknown | 364 | 2.9% | 100 | 2.4% | 135 | 3.2% | 129 | 3.2% | |

| Maternal employment | Yes | 8592 | 69.5% | 2766 | 65.6% | 2884 | 69.2% | 2942 | 73.9% |

| No | 3775 | 30.5% | 1453 | 34.4% | 1284 | 30.8% | 1038 | 26.1% | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Maternal mental condition | K6: <5 | 8522 | 68.9% | 2,998 | 71.1% | 2872 | 68.9% | 2652 | 66.6% |

| K6: 5+ | 3794 | 30.7% | 1204 | 28.5% | 1284 | 30.8% | 1306 | 32.8% | |

| Missing | 51 | 0.4% | 17 | 0.4% | 12 | 0.3% | 22 | 0.6% | |

| Number of consulting sources | None | 1174 | 9.5% | 474 | 11.2% | 350 | 8.4% | 350 | 8.8% |

| One to two | 7848 | 63.5% | 2,565 | 60.8% | 2704 | 64.9% | 2579 | 64.8% | |

| Three to four | 2964 | 24.0% | 1022 | 24.2% | 993 | 23.8% | 949 | 23.8% | |

| Five+ | 371 | 3.0% | 148 | 3.5% | 121 | 2.9% | 102 | 2.6% | |

| Outcome variable | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | |

| SDQ total | (Range: 0–40) | 10.3 | 5.41 | 9.93 | 5.31 | 10.4 | 5.42 | 10.5 | 5.46 |

| SDQ-prosocial | (Range: 0–10) | 6.65 | 2.07 | 6.61 | 2.04 | 6.69 | 2.06 | 6.66 | 2.09 |

| N | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | ≥3,000,000 yen | 9582 | 77.5% | |

| <3,000,000 yen | 1210 | 9.78% | ||

| No response | 1575 | 12.7% | ||

| Child-related deprivation | Material hardship | Books | 217 | 1.75% |

| Toys | 143 | 1.16% | ||

| Place to study | 364 | 2.94% | ||

| Payment difficulty | Trips | 78 | 0.63% | |

| Excursions | 36 | 0.29% | ||

| School lunch | 162 | 1.31% | ||

| Any child-related deprivation | 672 | 5.43% | ||

| Life-related deprivation | Material hardship | Washing machine | 31 | 0.25% |

| Cooking appliances | 27 | 0.22% | ||

| Cleaning appliances | 33 | 0.27% | ||

| Heating | 54 | 0.44% | ||

| Air conditioning | 54 | 0.44% | ||

| Oven | 41 | 0.33% | ||

| Phone | 147 | 1.19% | ||

| Bath | 34 | 0.27% | ||

| Bed | 315 | 2.55% | ||

| Savings | 1304 | 10.5% | ||

| Payment difficulty | Rent | 197 | 1.59% | |

| Mortgage | 81 | 0.65% | ||

| Electricity | 218 | 1.76% | ||

| Gas | 194 | 1.57% | ||

| Water | 189 | 1.53% | ||

| Phone | 207 | 1.67% | ||

| Premiums | 704 | 5.69% | ||

| Transportation | 45 | 0.36% | ||

| Any life-related deprivation | 1904 | 15.2% | ||

| Combinations of dimensions of poverty | ||||

| None of the three dimensions of poverty | 8385 | 67.8% | ||

| Low income and child-related deprivation | 53 | 0.43% | ||

| Low income and life-related deprivation | 340 | 2.75% | ||

| Child-related and life-related deprivation | 244 | 1.97% | ||

| All three dimensions of poverty | 177 | 1.43% | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | S.E. | p-Value | Coef | S.E. | p-Value | Coef | S.E. | p-Value | ||

| Child sex (ref: female) | Male | 0.238 | 0.017 | <0.001 | 0.236 | 0.017 | <0.001 | 0.237 | 0.017 | <0.001 |

| Child age | (Months) | −0.028 | 0.002 | <0.001 | −0.028 | 0.002 | <0.001 | −0.028 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Number of parents living at home (ref: two parents) | One parent | 0.033 | 0.037 | 0.374 | 0.020 | 0.037 | 0.590 | 0.017 | 0.037 | 0.647 |

| None, other | 0.365 | 0.109 | 0.001 | 0.353 | 0.109 | 0.001 | 0.361 | 0.109 | 0.001 | |

| Number of grandparents living at home (ref: none) | One grandparent | 0.107 | 0.039 | 0.006 | 0.109 | 0.039 | 0.005 | 0.107 | 0.039 | 0.006 |

| Two+ grandparents | 0.043 | 0.043 | 0.319 | 0.048 | 0.043 | 0.259 | 0.046 | 0.043 | 0.283 | |

| Number of children in the household (ref: one child) | Two children | −0.189 | 0.023 | <0.001 | −0.188 | 0.023 | <0.001 | −0.190 | 0.023 | <0.001 |

| Three children | −0.259 | 0.027 | <0.001 | −0.265 | 0.027 | <0.001 | −0.274 | 0.027 | <0.001 | |

| Four+ children | −0.232 | 0.042 | <0.001 | −0.256 | 0.042 | <0.001 | −0.274 | 0.043 | <0.001 | |

| Maternal age | 30–34 (years old) | −0.088 | 0.043 | 0.040 | −0.085 | 0.043 | 0.046 | −0.073 | 0.043 | 0.088 |

| (ref: age < 30) | 35–39 | −0.181 | 0.041 | <0.001 | −0.177 | 0.041 | <0.001 | −0.161 | 0.041 | <0.001 |

| 40–44 | −0.202 | 0.041 | <0.001 | −0.196 | 0.041 | <0.001 | −0.175 | 0.041 | <0.001 | |

| 45+ | −0.266 | 0.047 | <0.001 | −0.262 | 0.046 | <0.001 | −0.242 | 0.046 | <0.001 | |

| Maternal education | High school or less | 0.185 | 0.024 | <0.001 | 0.176 | 0.024 | <0.001 | 0.159 | 0.024 | <0.001 |

| (ref: university/grad school) | Technical school, small college | 0.060 | 0.022 | 0.007 | 0.057 | 0.022 | 0.010 | 0.050 | 0.022 | 0.025 |

| Other | 0.128 | 0.065 | 0.047 | 0.122 | 0.065 | 0.058 | 0.108 | 0.064 | 0.093 | |

| Maternal unemployment | (ref: employed) | −0.060 | 0.019 | 0.001 | −0.057 | 0.019 | 0.002 | −0.053 | 0.019 | 0.005 |

| Parental psychological distress (ref: no) | Yes (K6: 5+) | 0.544 | 0.019 | <0.001 | 0.530 | 0.019 | <0.001 | 0.524 | 0.019 | <0.001 |

| Number of consulting sources (ref: five+) | Three to four | 0.039 | 0.053 | 0.462 | 0.039 | 0.053 | 0.460 | 0.043 | 0.053 | 0.416 |

| One to two | 0.146 | 0.051 | 0.004 | 0.145 | 0.051 | 0.004 | 0.144 | 0.051 | 0.004 | |

| None | 0.319 | 0.058 | <0.001 | 0.303 | 0.058 | <0.001 | 0.301 | 0.058 | <0.001 | |

| Year of survey (ref: 2015) | 2017 | 0.053 | 0.021 | 0.012 | 0.057 | 0.021 | 0.007 | 0.057 | 0.021 | 0.007 |

| 2019 | 0.069 | 0.022 | 0.001 | 0.071 | 0.022 | 0.001 | 0.075 | 0.022 | 0.001 | |

| Low income | <3M yen | 0.057 | 0.034 | 0.095 | 0.033 | 0.034 | 0.340 | 0.013 | 0.034 | 0.695 |

| (ref: >3M yen) | Missing | 0.013 | 0.026 | 0.628 | 0.011 | 0.026 | 0.678 | 0.012 | 0.026 | 0.654 |

| Child deprivation (ref: none) | One or more | 0.252 | 0.040 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Life deprivation (ref: none) | One or more | 0.220 | 0.026 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | S.E. | p-Value | Coef | S.E. | p-Value | Coef | S.E. | p-Value | ||

| Child sex (ref: female) | Male | −0.355 | 0.018 | <0.001 | −0.355 | 0.018 | <0.001 | −0.355 | 0.018 | <0.001 |

| Child age | (Months) | 0.019 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Number of parents living at home (ref: two parents) | One parent | 0.072 | 0.039 | 0.063 | 0.072 | 0.039 | 0.066 | 0.071 | 0.039 | 0.067 |

| None, other | −0.172 | 0.114 | 0.132 | −0.173 | 0.114 | 0.131 | −0.172 | 0.114 | 0.132 | |

| Number of grandparents living at home (ref: none) | One grandparent | −0.036 | 0.041 | 0.375 | −0.036 | 0.041 | 0.377 | −0.036 | 0.041 | 0.376 |

| Two + grandparents | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.319 | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.315 | 0.045 | 0.045 | 0.316 | |

| Number of children in the household (ref: one child) | Two children | −0.027 | 0.024 | 0.269 | −0.027 | 0.024 | 0.271 | −0.027 | 0.024 | 0.269 |

| Three children | −0.004 | 0.028 | 0.887 | −0.004 | 0.028 | 0.877 | −0.005 | 0.028 | 0.862 | |

| Four + children | 0.020 | 0.044 | 0.649 | 0.019 | 0.044 | 0.674 | 0.018 | 0.045 | 0.692 | |

| Maternal age | 30–34 (years old) | −0.122 | 0.045 | 0.007 | −0.121 | 0.045 | 0.007 | −0.121 | 0.045 | 0.007 |

| (ref: age < 30) | 35–39 | −0.160 | 0.043 | <0.001 | −0.160 | 0.043 | <0.001 | −0.159 | 0.043 | <0.001 |

| 40–44 | −0.251 | 0.043 | <0.001 | −0.251 | 0.043 | <0.001 | −0.249 | 0.043 | <0.001 | |

| 45+ | −0.301 | 0.049 | <0.001 | −0.301 | 0.049 | <0.001 | −0.299 | 0.049 | <0.001 | |

| Maternal education | High school or less | 0.020 | 0.025 | 0.428 | 0.019 | 0.025 | 0.441 | 0.018 | 0.025 | 0.469 |

| (ref: university/grad school) | Technical school, small college | 0.002 | 0.023 | 0.941 | 0.002 | 0.023 | 0.947 | 0.001 | 0.023 | 0.963 |

| Other | 0.051 | 0.068 | 0.450 | 0.051 | 0.068 | 0.454 | 0.050 | 0.068 | 0.462 | |

| Maternal unemployment | (ref: employed) | 0.051 | 0.020 | 0.010 | 0.051 | 0.020 | 0.010 | 0.051 | 0.020 | 0.010 |

| Parental psychological distress (ref: no) | Yes (K6: 5+) | −0.109 | 0.020 | <0.001 | −0.109 | 0.020 | <0.001 | −0.110 | 0.020 | <0.001 |

| Number of consulting sources(ref: five+) | Three to four | −0.151 | 0.055 | 0.006 | −0.151 | 0.055 | 0.006 | −0.151 | 0.055 | 0.006 |

| One to two | −0.284 | 0.053 | <0.001 | −0.284 | 0.053 | <0.001 | −0.284 | 0.053 | <0.001 | |

| None | −0.408 | 0.061 | <0.001 | −0.409 | 0.061 | <0.001 | −0.409 | 0.061 | <0.001 | |

| Year of survey (ref: 2015) | 2017 | 0.062 | 0.022 | 0.005 | 0.062 | 0.022 | 0.005 | 0.062 | 0.022 | 0.005 |

| 2019 | 0.053 | 0.023 | 0.019 | 0.053 | 0.023 | 0.019 | 0.053 | 0.023 | 0.019 | |

| Low income | <3M yen | 0.040 | 0.036 | 0.259 | 0.039 | 0.036 | 0.280 | 0.038 | 0.036 | 0.297 |

| (ref: >3M yen) | missing | 0.022 | 0.028 | 0.435 | 0.021 | 0.028 | 0.438 | 0.022 | 0.028 | 0.437 |

| Child deprivation (ref: none) | One or more | 0.015 | 0.042 | 0.721 | ||||||

| Life deprivation (ref: none) | One or more | 0.013 | 0.027 | 0.621 | ||||||

| Income | % of total effect | |||

| coef | S.E. | p-value | ||

| Total effect | 0.129 | 0.035 | <0.001 | |

| Direct effect | 0.060 | 0.034 | 0.077 | 46.3% |

| Indirect effect via parental psychological distress | 0.058 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 45.0% |

| Indirect effect via number of consulting sources | 0.027 | 0.004 | <0.001 | 20.8% |

| Life-related deprivation | % of total effect | |||

| coef | S.E. | p-value | ||

| Total effect | 0.355 | 0.026 | <0.001 | |

| Direct effect | 0.234 | 0.025 | <0.001 | 66.0% |

| Indirect effect via parental psychological distress | 0.104 | 0.007 | <0.001 | 29.2% |

| Indirect effect via number of consulting sources | 0.023 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 6.4% |

| Child-related deprivation | % of total effect | |||

| coef | S.E. | p-value | ||

| Total effect | 0.458 | 0.041 | <0.001 | |

| Direct effect | 0.274 | 0.040 | <0.001 | 59.9% |

| Indirect effect via parental psychological distress | 0.160 | 0.012 | <0.001 | 35.0% |

| Indirect effect via number of consulting sources | 0.031 | 0.005 | <0.001 | 6.9% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamaoka, Y.; Isumi, A.; Doi, S.; Ochi, M.; Fujiwara, T. Differential Effects of Multiple Dimensions of Poverty on Child Behavioral Problems: Results from the A-CHILD Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211821

Yamaoka Y, Isumi A, Doi S, Ochi M, Fujiwara T. Differential Effects of Multiple Dimensions of Poverty on Child Behavioral Problems: Results from the A-CHILD Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(22):11821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211821

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamaoka, Yui, Aya Isumi, Satomi Doi, Manami Ochi, and Takeo Fujiwara. 2021. "Differential Effects of Multiple Dimensions of Poverty on Child Behavioral Problems: Results from the A-CHILD Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22: 11821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211821

APA StyleYamaoka, Y., Isumi, A., Doi, S., Ochi, M., & Fujiwara, T. (2021). Differential Effects of Multiple Dimensions of Poverty on Child Behavioral Problems: Results from the A-CHILD Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11821. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211821