Eritrean Refugees’ and Asylum-Seekers’ Attitude towards and Access to Oral Healthcare in Heidelberg, Germany: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Sampling Procedures

2.3. Data Collection Instrument and Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Consideration

3. Results

3.1. Perception of Oral Health Care

“I believe Berbere protects you from bad mouth odour! As for me, I am getting Berbere from home [Eritrea] solely prepared by my mother, and I am consuming it every day. You know what […]? as Berbere is my routine food, I do not have any terribly smelling mouth like others do” (IDI-13).

3.2. Understanding of oral Health Determinants

“Life in Europe is somehow different from our country. Most of us here [in Germany] we tend to change our lifestyle. We start to eat differently, like sweet and packaged food that are not common in our country; starting from me, smoking isn’t also uncommon. I believe that those things are the reason for my poor oral health” (IDI-4).

3.3. Dental Care Behaviour

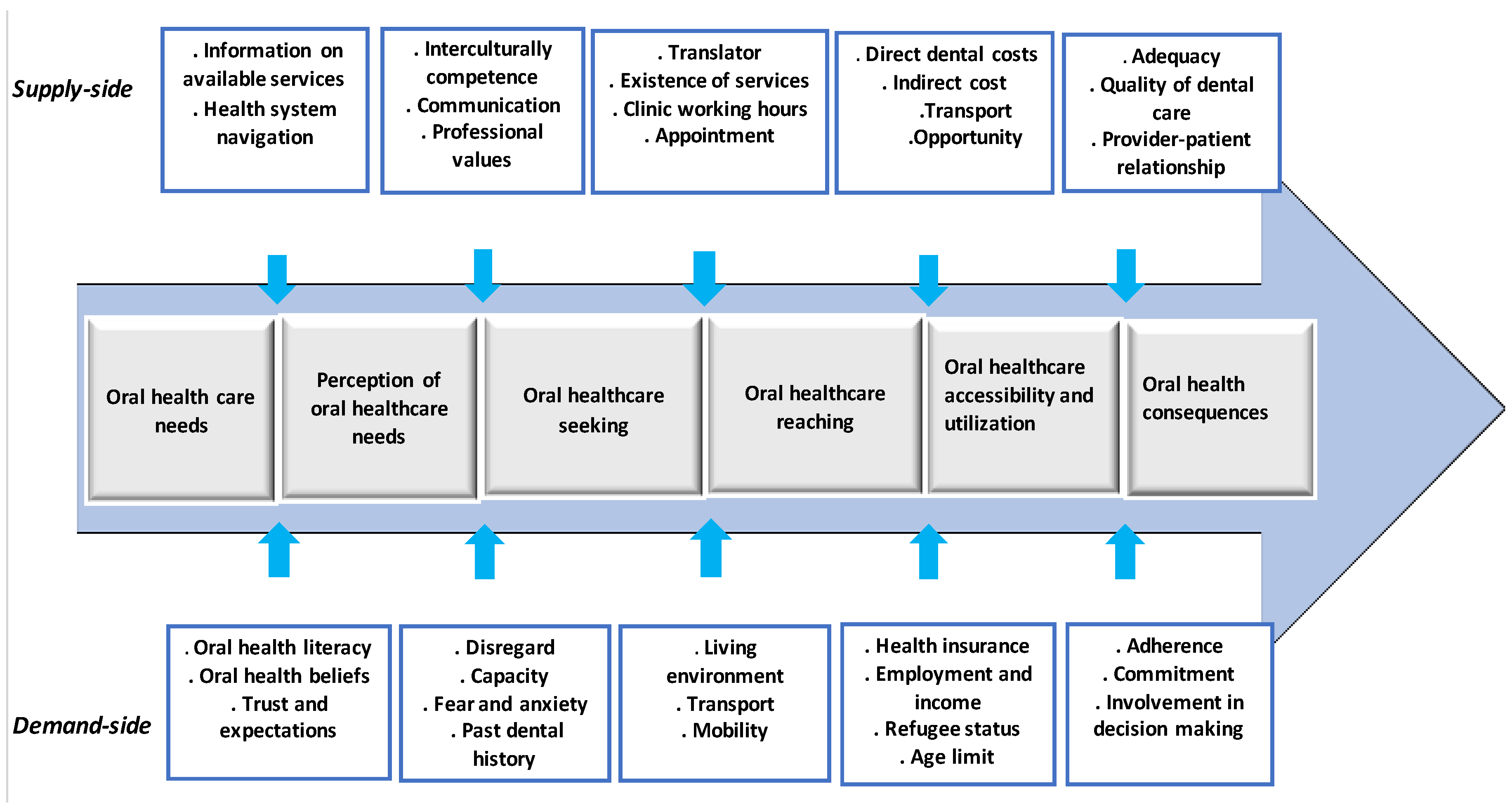

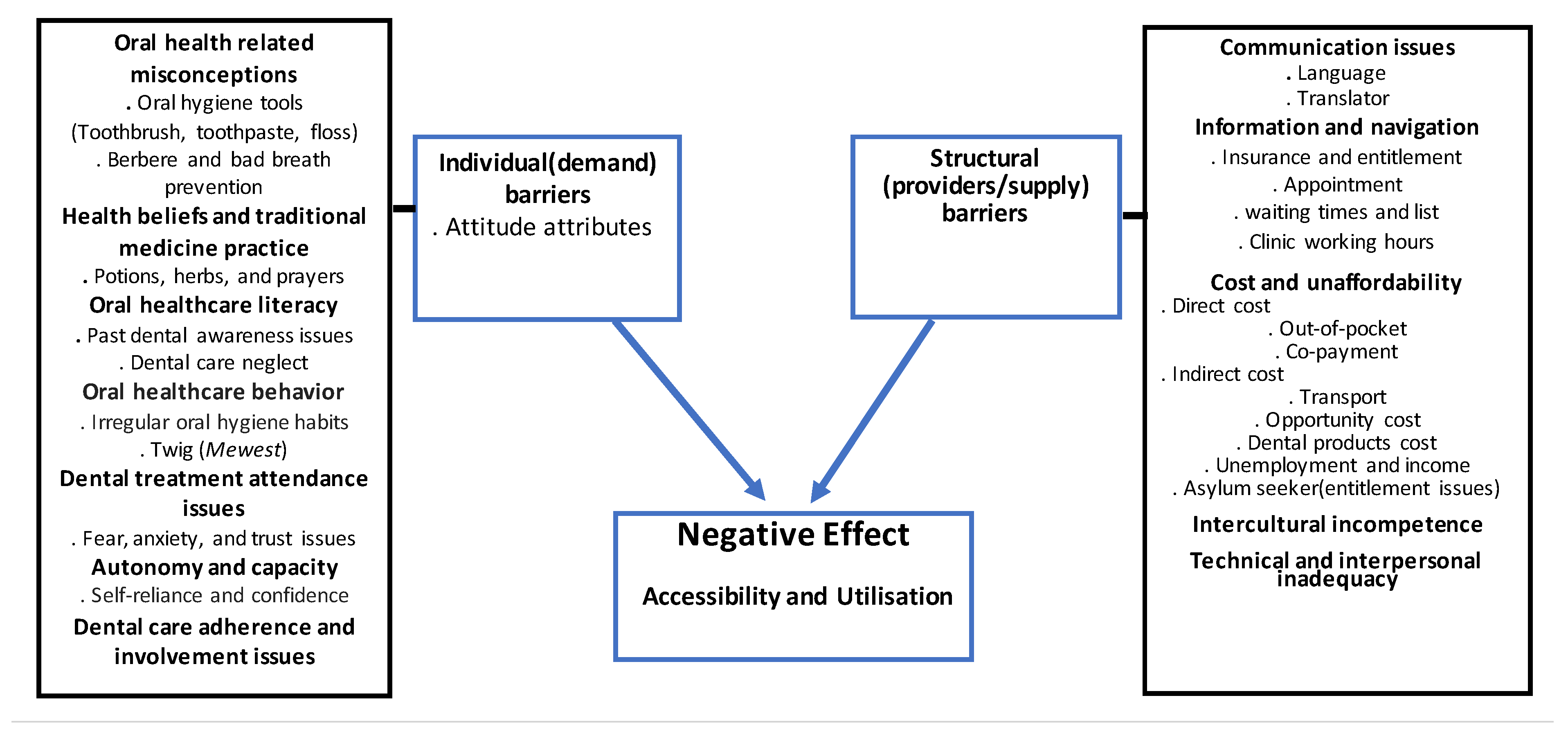

3.4. Approachability and Ability to Perceive

“Back in our country [Eritrea], if we experience any kind of illness, we don’t simply go to the clinic […]. Our parents and community healers used to give us any traditional herbs, potions, and spells. Then we wait for God to heal us. Likewise, here [in Germany] even though I am not using the herbs and potions […], I simply don’t go to the clinic, I just pray at home and wait for God to heal me from my misery” (FGD-1).

“Sometimes though, the dentists work on a tooth that you have not complained about and we might not be comfortable with it too. As far as I am concerned, I don’t like it” (IDI-13).

“For some of us, it is like we don’t even trust some of the dentists in Germany. I think that when they [dentists] are taking out our teeth, they want to do so in their own interest, and to replace ours with artificial teeth, which is not in our interest” (FGD-1).

“I don’t trust the dentists too. I have a trust issue! I mean […], the bureaucracy is very tedious […], they tell you to sign here, and there […], I don’t know what we are sometimes saying. Who knows, later they [dentists] might ask us to pay all (laughter)?” (FGD-1).

3.5. Acceptability and Ability to Seek

“The dentists should try to understand our difficulties in learning the new culture here [Germany]. In our country [Eritrea], we have a different background and practice for tooth care. We don’t know much about the new way of dental care in Germany […], but we used to treat dental pain with herbs. Thus, the doctors should show some kindness and teach us calmly the correct way […]. My dentist expects me to comply to whatever he said, and he is very rigid and strict […]. I really didn’t understand his instructions and he once yelled at me too (sigh)” (FGD-1).

“As far as I am concerned, the reason behind my hesitation in visiting a dental clinic, despite experiencing marked dental problems, is that I had been through a very bad experience on my way to Europe. I saw and witnessed a lot of awful distress and health problems along my way in Sahara, Libya or at sea [Mediterranean]. Comparing to those, I consider my teeth problem as a simple discomfort and I just resist the pain until it resolves itself” (FGD-1).

“I chose not to go back after six months because I hate the machines that trim the teeth. Do you know how annoying are the rotating machines and the other sharp instruments that they [dentists] use? For example, one day, I had experienced a severe headache because of the instruments that they had stuck into my teeth; honestly, I hated it. Now that I am treated, thanks God it’s over […]. It has been three years since I have experienced any kind of dental problem, and I never been in a dental surgery after that too” (IDI-15).

3.6. Availability and Accommodation and Ability to Reach

“Most of the appointments that you get are on weekdays […], where most of us are busy at work or school […]. They [dentists] won’t see you at weekends. So, if we need further visits, we couldn’t miss work or classes so often […]. Thus, we often miss follow-up appointments” (FGD-1).

“I can say that there is some problem, especially for those who reside in villages, where train transport is unpredictable […]. Pregnant mothers have some access problems. My friend’s wife was once caught up in such a difficulty” (FGD-1).

3.7. Affordability and Ability to Pay

“In my opinion, comparing with the other services, dental care is expensive, and it always requires several consecutive appointments so that you need to skip work, pay for trains, and dental products like tooth brush, paste or mouthwash” (IDI-1).

“I haven’t had enough money to get the treatment [orthodontic treatment], because I have no work or income” (IDI-4).

3.8. Appropriateness and Ability to Engage

“My dentist once informed me that my tooth was decayed and suggested to extract it, and I simply agreed. Then when he [the dentist] attempted the extraction, it took him six hours. Since the tooth was decayed only on the upper part not at root, I should have asked him to restore it. It was my mistake. I was looking for a temporary solution but it cost me a lot and my left cheek was really numb for the following six months” (IDI-3).

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | |

|---|---|

| 1. | What is the first thing that comes to your mind when you hear about oral health? |

| 2. | What is good oral health to you? What about oral healthcare? |

| 3. | How concerned are you about your oral health? |

| 4. | What is your opinion on the relationship of poor oral health and general health? |

| 5. | Thinking as ERNRAS, how would you describe your overall oral health status? |

| 6. | What do you think the risk factors for the poor oral health among ERNRAS? |

| 7. | Can you talk about the oral hygiene tools you are using? How often are you using? |

| 8. | what is your opinion on ‘when a dentist should be visited?’ |

| 10. | Can you tell me what are the main factors hindering ERNRAS from demanding oral healthcare services in Germany? |

| 11. | what is your opinion on how oral health issues of refugees should be managed at the individual, community, governmental or policy levels? |

Appendix B

| Themes and Sub-themes | Pertinent Findings According to Participants (ERNRAS) | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of Oral Healthcare | ||

| Perceived definition of oral health |

| “we shouldn’t have a dental cavity, oral ulcers, bad mouth odour or no broken or crooked tooth” (FGD-1). |

| Social acceptance and Self-esteem |

| “If we don’t have good teeth, we don’t have a girlfriend (laughter)” (FGD-1). “After I knew from my friends about the smell of my mouth […], it wasn’t good news […], I soon lost my confidence and couldn’t stand talking to people.” (IDI-14). “Then, I wouldn’t stop eating Berbere so that I could stay free of bad breath” (IDI-8). |

| Understanding of Oral Health Determinants | ||

| Awareness of oral health as holistic health |

| “Tooth has to be cleaned and kept healthy so that we can eat nutritious foods and we live longer” (IDI-11). |

| Perceived risks of poor oral health |

| “Here [Germany], we, Eritreans, are consuming a lot of sweet, soft, and packed food, unlike the food we used to eat in our country, which was hard to chew and less sweet. I believe this is the reason for this poor oral health” (IDI-5). |

| Dental Care Behaviour | ||

| Personal dental care |

| “I always clean my teeth in the morning, right after I eat my breakfast, and sometimes in the evening—before I went to bed” (IDI-3). “I don’t have any idea about this thread, and I have never used one in my life” (FGD-2). “Not always and only, but I sometimes use Mewets if I can find a good tree” (IDI-15). |

| Professional dental care |

| “I only go to a dentist for an essential treatment; for example, I once went to a dental clinic for a severe dental pain” (IDI-3). “I check my tooth every six months; it doesn’t matter whether I have a problem or not.” (IDI- 2) |

| Misperception of oral healthcare practice |

| “From my understanding […], and from what I heard, the chemical in the toothpaste is destructive to our teeth.” (FGD-1). “I guess it might damage our teeth or gum. So, I don’t have any plans to use it” (IDI-14) |

| Approachability and Ability to Perceive | ||

| Information about availability and navigation of the oral healthcare system |

| “I don’t know where and how to find it [dental clinic” (IDI-6). “I don’t know even whether a regular visiting is free. I am just hearing now that I could go to a dentist on a twice a year basis”(IDI-12). |

| Oral health literacy and beliefs |

| “In our case [Eritreans], […] we were neither screened nor taught to take care of our teeth when we were in our country. Then we grew up known nothing, and it is costing us a lot to learn to take good care of our teeth. We are simply detached of the reality” (FGD-2). |

| The level of trust and Expectations from a dentist |

| “When they [dentists] are taking out our tooth, they want to use it [tooth] for their interest and replace ours with artificial tooth”(FGD-1). |

| Acceptability and Ability to Seek | ||

| Interculturally competent professionals |

| “I can say my first dentist could have done more […]. Not only he doesn’t want to hear my opinion, but also wanted me to follow his instructions only. That’s why the treatment he provided that time couldn’t satisfy me” (IDI-3). |

| Lack of communication and professional value |

| “There is one staff, she doesn’t really hear you what you want to say, I don’t know why, she is either racist or arrogant” (IDI-4). |

| Autonomy and capacity to seek oral healthcare |

| “Sometimes, even though we are in a great misery and needed treatment, we don’t go to the dentist due to lack of confidence the language barrier puts us into” (FGD-1). |

| Disregard or negligence |

| “Dental care never been my priority […], unless I have a serious pain, I don’t care to visit a dentist for a minor discomfort” (IDI-6). |

| Fear, anxiety and past dental experience |

| “Dental appointment is good, [..] but I would never go to my dentist for a regular check-up unless I have pain; I am scared of the machines”(FGD-2). |

| Availability and Accommodation and ability to reach | ||

| Language issues and Availability of translator |

| “It is the language problem I have; I can’t tell a dentist what is really happening to me, and that is why I didn’t go to the dentist” (IDI-6). |

| Existence of dental services, hours of opening and appointment |

| “Sometimes the long waiting time and all […], we [refugees] don’t visit unless we have serious problem or pain” (IDI-11). |

| Living environment and mobility |

| “Well, earlier my dental clinic wasn’t that far, now that I have changed my residence area to small village, it’s a bit far from my dental clinic. I am not going to the dental clinic, maybe because of this” (IDI-5). |

| Affordability and Ability to pay | ||

| Direct and Indirect cost |

| “And, the other day that I didn’t visit my dentist might have been due to the instinct I developed to avoid paying money to the dentist as it is crazy expensive”(IDI-3). |

| Entitlement based on age, refugee and employment status |

| “I wanted to check and clean my teeth. However, I couldn’t get the treatment, both cleaning and filling my teeth, [..] because I wasn’t entitled to that treatment as I was an asylum seeker” (FGD-2). “Dental treatment is so expensive that I can’t really afford it since a I am not working right now” (IDI-3). |

| Appropriateness and ability to engage | ||

| Adequacy and quality of the dental care providers |

| “I always think that, at my first visit, the dentist could have given me more information. He [dentist] should have checked my teeth very well and he should have filled it instead of removing” (IDI-3). |

| Provider-patient relationships |

| “Some of the nurses in the reception shows you bad attitude and are not friendly” (IDI-2). |

| Adherence and involvement of ERNRAS in dental treatments |

| “Most of us [refugees] are not registered with the town’s refugee collaboration community, where we could have participated and seek help when we face difficulty in understanding and accessing the dental services” (IDI-7). |

References

- UNHCR. Global Trends—Forced Displacement in 2018. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2018/ (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- UNHCR. Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/protection/basic/3b66c2aa10/convention-protocol-relating-status-refugees.html (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- UNHCR. UNHCR Master Glossary of Terms. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/42ce7d444.html (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Statistics on Migration to Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/promoting-our-european-way-life/statistics-migration-europe_en (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- UNHCR—Global Trends 2019: Forced Displacement in 2019. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2019/ (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- World Population Prospects. Population Division, United Nations. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/Maps/ (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- BAMF. Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge. Available online: https://www.BAMF.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Statistik/Asylgeschaeftsbericht/201812-statistik-anlage-asyl-geschaeftsbericht.html?nn=284730 (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Kohlenberger, J.; Buber-Ennser, I.; Rengs, B.; Leitner, S.; Landesmann, M. Barriers to Health Care Access and Service Utilization of Refugees in Austria: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Survey. Health Policy Amst. Neth. 2019, 123, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, T.G. The Healthy Immigrant (Migrant) Effect: In Search of a Better Native-Born Comparison Group. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 54, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shawyer, F.; Enticott, J.C.; Block, A.A.; Cheng, I.-H.; Meadows, G.N. The Mental Health Status of Refugees and Asylum Seekers Attending a Refugee Health Clinic Including Comparisons with a Matched Sample of Australian-Born Residents. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghiabi, E.; Matthews, D.C.; Brillant, M.S. The Oral Health Status of Recent Immigrants and Refugees in Nova Scotia, Canada. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2014, 16, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, N.; Skull, S.; Calache, H.; Murray, S.; Chalmers, J. Holes a Plenty: Oral Health Status a Major Issue for Newly Arrived Refugees in Australia. Aust. Dent. J. 2006, 51, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høyvik, A.C.; Lie, B.; Grjibovski, A.M.; Willumsen, T. Oral Health Challenges in Refugees from the Middle East and Africa: A Comparative Study. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2019, 21, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makan, R.; Gara, M.; Awwad, M.A.; Hassona, Y. The Oral Health Status of Syrian Refugee Children in Jordan: An Exploratory Study. Spec. Care Dentist. 2019, 39, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solyman, M.; Schmidt-Westhausen, A.-M. Oral Health Status among Newly Arrived Refugees in Germany: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goetz, K.; Winkelmann, W.; Steinhäuser, J. Assessment of Oral Health and Cost of Care for a Group of Refugees in Germany: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Oral Health 2018, 18, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Report on the Health of Refugees and Migrants in the WHO European Region: No Public Health without Refugee and Migrant Health. 2018. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/report-on-the-health-of-refugees-and-migrants-in-the-who-european-region-no-public-health-without-refugee-and-migrant-health-2018 (accessed on 28 January 2021).

- Sivakumar, V.; Jain, J.; Haridas, R.; Paliayal, S.; Rodrigues, S.; Jose, M. Oral Health Status of Tibetan and Local School Children: A Comparative Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR 2016, 10, ZC29–ZC33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deora, S.; Saini, A.; Bhatia, P.; Abraham, D.V.; Masoom, S.N.; Yadav, K. Periodontal Status among Tibetan Refugees Residing in Jodhpur City. J. Res. Dent. 2016, 3, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sugerman, D.E.; Hyder, A.A.; Nasir, K. Child and Young Adult Injuries among Long-Term Afghan Refugees. Int. J. Inj. Contr. Saf. Promot. 2005, 12, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.K.; Scott, T.E.; Henshaw, M.M.; Cote, S.E.; Grodin, M.A.; Piwowarczyk, L.A. Oral Health Status of Refugee Torture Survivors Seeking Care in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 2181–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cote, S.; Geltman, P.; Nunn, M.; Lituri, K.; Henshaw, M.; Garcia, R.I. Dental Caries of Refugee Children Compared with US Children. Pediatrics 2004, 114, e733–e740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Berlaer, G.; Carbonell, F.B.; Manantsoa, S.; de Béthune, X.; Buyl, R.; Debacker, M.; Hubloue, I. A Refugee Camp in the Centre of Europe: Clinical Characteristics of Asylum Seekers Arriving in Brussels. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e013963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keboa, M.T.; Hiles, N.; Macdonald, M.E. The Oral Health of Refugees and Asylum Seekers: A Scoping Review. Glob. Health 2016, 12, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattila, A.; Ghaderi, P.; Tervonen, L.; Niskanen, L.; Pesonen, P.; Anttonen, V.; Laitala, M.-L. Self-Reported Oral Health and Use of Dental Services among Asylum Seekers and Immigrants in Finland-a Pilot Study. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 1006–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, C.E.F.; Whelan, A.K.; Michaels, C. Refugees and Oral Health: Lessons Learned from Stories of Hazara Refugees. Aust. Health Rev. Publ. Aust. Hosp. Assoc. 2009, 33, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geltman, P.L.; Adams, J.H.; Cochran, J.; Doros, G.; Rybin, D.; Henshaw, M.; Barnes, L.L.; Paasche-Orlow, M. The Impact of Functional Health Literacy and Acculturation on the Oral Health Status of Somali Refugees Living in Massachusetts. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keboa, M.; Nicolau, B.; Hovey, R.; Esfandiari, S.; Carnevale, F.; Macdonald, M.E. A Qualitative Study on the Oral Health of Humanitarian Migrants in Canada. Community Dent. Health 2019, 36, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, M.S.; Bothun, R.M. Oral Hygiene Knowledge and Practice Among Dinka and Nuer from Sudan to the U.S. Am. Dent. Hyg. Assoc. 2011, 85, 306–315. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs, E.; Gibbs, L.; Kilpatrick, N.; Gussy, M.; van Gemert, C.; Ali, S.; Waters, E. Breaking down the Barriers: A Qualitative Study to Understand Child Oral Health in Refugee and Migrant Communities in Australia. Ethn. Health 2015, 20, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S Dhull, K.; Dutta, B.; M Devraj, I.; Samir, P. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Mothers towards Infant Oral Healthcare. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2018, 11, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asylum Act (AsylG). Available online: https://www.BAMF.de/SharedDocs/Links/EN/G/gesetze-im-internet-asylvfg.html?nn=285460 (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Davidson, N.; Skull, S.; Chaney, G.; Frydenberg, A.; Isaacs, D.; Kelly, P.; Lampropoulos, B.; Raman, S.; Silove, D.; Buttery, J.; et al. Comprehensive Health Assessment for Newly Arrived Refugee Children in Australia. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2004, 40, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvasina, P.; Muntaner, C.; Quiñonez, C. Factors Associated with Unmet Dental Care Needs in Canadian Immigrants: An Analysis of the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, A.; Laemmle-Ruff, I.L.; Polizzi, T.; Paxton, G.A. Gaps in Smiles and Services: A Cross-Sectional Study of Dental Caries in Refugee-Background Children. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Petersen, P.E. The World Oral Health Report 2003: Continuous Improvement of Oral Health in the 21st Century—The Approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2003, 31, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautemaa, R.; Lauhio, A.; Cullinan, M.P.; Seymour, G.J. Oral Infections and Systemic Disease—an Emerging Problem in Medicine. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2007, 13, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Kolltveit, K.M.; Tronstad, L.; Olsen, I. Systemic Diseases Caused by Oral Infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, H.; Lindholm, E.; Lindh, C.; Groop, L.; Bratthall, G. Type 2 Diabetes and Risk for Periodontal Disease: A Role for Dental Health Awareness. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2006, 33, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, T.; Webb, I.; Stenhouse, L.; Pattni, A.; Ready, D.; Wanyonyi, K.L.; White, S.; Gallagher, J.E. Evidence Summary: The Relationship between Oral and Cardiovascular Disease. Br. Dent. J. 2017, 222, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pani, S.C.; Al-Sibai, S.A.; Rao, A.S.; Kazimoglu, S.N.; Mosadomi, H.A. Parental Perception of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Syrian Refugee Children. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2017, 7, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Awwad, M.; AL-Omoush, S.; Shqaidef, A.; Hilal, N.; Hassona, Y. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life among Syrian Refugees in Jordan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. Dent. J. 2020, 70, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunbodede, E.O.; Mickenautsch, S.; Rudolph, M.J. Oral Health Care in Refugee Situations: Liberian Refugees in Ghana. J. Refug. Stud. 2000, 13, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Access to Healthcare. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/access-to-healthcare.html (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Pottie, K.; Greenaway, C.; Feightner, J.; Welch, V.; Swinkels, H.; Rashid, M.; Narasiah, L.; Kirmayer, L.J.; Ueffing, E.; MacDonald, N.E.; et al. Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for Immigrants and Refugees. CMAJ 2011, 183, E824–E925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polkinghorne, D.E. Phenomenological Research Methods. In Existential-Phenomenological Perspectives in Psychology: Exploring the Breadth of Human Experience; Valle, R.S., Halling, S., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 41–60. ISBN 978-1-4615-6989-3. [Google Scholar]

- The 2018 Migration Report. Available online: https://www.BAMF.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/EN/Forschung/Migrationsberichte/migrationsbericht-2018.html?nn=403964 (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- Initial Distribution of Asylum-Seekers (EASY). Available online: https://www.BAMF.de/EN/Themen/AsylFluechtlingsschutz/AblaufAsylverfahrens/Erstverteilung/erstverteilung-node.html (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Heidelberg.de. Arrival Center for Baden-Württemberg. Available online: https://www.heidelberg.de/english/Home/Life/arrival+center+for+baden-wuerttemberg.html (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- Heidelberg.de. Refugees in Heidelberg. Available online: https://www.heidelberg.de/english/Home/Life/refugees+in+heidelberg.html (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball Sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 32, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, J.-F.; Harris, M.F.; Russell, G. Patient-Centred Access to Health Care: Conceptualising Access at the Interface of Health Systems and Populations. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboul-Enein, B.H. The Miswak (Salvadora Persica L.) Chewing Stick: Cultural Implications in Oral Health Promotion. Saudi J. Dent. Res. 2014, 5, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, Y. Contribution of Trees for Oral Hygiene in East Africa. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2007, 2007, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Prowse, S.; Schroth, R.J.; Wilson, A.; Edwards, J.M.; Sarson, J.; Levi, J.A.; Moffatt, M.E. Diversity Considerations for Promoting Early Childhood Oral Health: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Dent. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, I.V.; Stephen, S.; Barker, J.C.; Weintraub, J.A. Cultural Factors and Children’s Oral Health Care: A Qualitative Study of Carers of Young Children. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2007, 35, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, C. Talking about Teeth—Exploring the Barriers to Accessing Oral Health Services for Horn of Africa Community Members Living in Inner West Melbourne. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Talking-about-Teeth-exploring-the-barriers-to-oral-Hobbs/a8ba1491d521e1cfbf8e6a3026a0b0a16d5043b4 (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Loizzo, M.R.; Lecce, G.D.; Boselli, E.; Bonesi, M.; Menichini, F.; Menichini, F.; Frega, N.G. In Vitro Antioxidant and Hypoglycemic Activities of Ethiopian Spice Blend Berbere. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 62, 740–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmboe-Ottesen, G.; Wandel, M. Changes in Dietary Habits after Migration and Consequences for Health: A Focus on South Asians in Europe. Food Nutr. Res. 2012, 56, 18891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.H.; Young, S.; Laird, L.D.; Geltman, P.L.; Cochran, J.J.; Hassan, A.; Egal, F.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Barnes, L.L. The Cultural Basis for Oral Health Practices among Somali Refugees Pre- and Post-Resettlement in Massachusetts. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2013, 24, 1474–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggs, E.; Yelland, J.; Shankumar, R.; Kilpatrick, N. ‘We Are All Scared for the Baby’: Promoting Access to Dental Services for Refugee Background Women during Pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevan, J.K.; Yacob, T.; Abdurhman, N.; Asmerom, S.; Birhane, T.; Sebri, J.; Kaushik, A. Eritrean Chewing Sticks Potential against Isolated Dental Carries Organisms from Dental Plaque. Arch. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, R.S. Odor-Associative Learning and Emotion: Effects on Perception and Behavior. Chem. Senses 2005, 30, i250–i251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andegiorgish, A.K.; Weldemariam, B.W.; Kifle, M.M.; Mebrahtu, F.G.; Zewde, H.K.; Tewelde, M.G.; Hussen, M.A.; Tsegay, W.K. Prevalence of Dental Caries and Associated Factors among 12 Years Old Students in Eritrea. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño, R.; Wright, C.; Schofield, M.; Minichiello, V.; Calache, H. Factors Associated with Self-Reported Use of Dental Health Services among Older Greek and Italian Immigrants. Spec. Care Dentist. 2005, 25, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.; Skull, S.; Calache, H.; Chesters, D.; Chalmers, J. Equitable Access to Dental Care for an At-Risk Group: A Review of Services for Australian Refugees. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2007, 31, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdsiek, F.; Waury, D.; Brzoska, P. Oral Health Behaviour in Migrant and Non-Migrant Adults in Germany: The Utilization of Regular Dental Check-Ups. BMC Oral Health 2017, 17, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjögren Forss, K.; Mangrio, E. Scoping Review of Refugees’ Experiences of Healthcare. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Borgschulte, H.S.; Wiesmüller, G.A.; Bunte, A.; Neuhann, F. Health Care Provision for Refugees in Germany—One-Year Evaluation of an Outpatient Clinic in an Urban Emergency Accommodation. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, C.F.; Smith, M. Problems Refugees Face When Accessing Health Services. New South Wales Public Health Bull. 2002, 13, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, J.T.; Thorogood, N.; Bhavnani, V.; Pitt, J.; Gibbons, D.E.; Gelbier, S. Barriers to the Use of Dental Services by Individuals from Minority Ethnic Communities Living in the United Kingdom: Findings from Focus Groups. Prim. Dent. Care 2001, 8, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgmehr, K.; Razum, O. Effect of Restricting Access to Health Care on Health Expenditures among Asylum-Seekers and Refugees: A Quasi-Experimental Study in Germany, 1994–2013. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphris, R.; Bradby, H. Health Status of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Europe. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/publichealth/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.001.0001/acrefore-9780190632366-e-8 (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G.; Pilotta, J.J. Naturalistic Inquiry Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, 1985, 416 pp. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1985, 9, 438–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzic, A.; Waldman, S. Chronic Diseases: The Emerging Pandemic. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2011, 4, 225–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age range (Years) | |||

| 18–25 | 11 | 44% | |

| 26–35 | 9 | 36% | |

| 36–45 | 5 | 16% | |

| 46–55 | 1 | 4% | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 19 | 76% | |

| Female | 6 | 24% | |

| Educational Level (Years attending school) | |||

| Primary (1–5) | 2 | 8% | |

| Middle (6–8) | 4 | 16% | |

| Secondary (9–12) | 14 | 56% | |

| Higher (13+) | 5 | 20% | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 7 | 28% | |

| Unmarried | 18 | 72% | |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed | 15 | 60% | |

| Unemployed | 10 | 40% | |

| Stay in Germany (Years) | |||

| ≤3 | 7 | 28% | |

| >3 | 19 | 72% | |

| Place of Residence | |||

| Heidelberg | 15 | 60% | |

| Eppelheim | 3 | 12% | |

| Plankstadt | 2 | 8% | |

| Dossennheim | 3 | 12% | |

| Bammental | 2 | 8% | |

| Refugee Status | |||

| Refugee | 21 | 84% | |

| Asylum seeker | 4 | 16% | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kidane, Y.S.; Ziegler, S.; Keck, V.; Benson-Martin, J.; Jahn, A.; Gebresilassie, T.; Beiersmann, C. Eritrean Refugees’ and Asylum-Seekers’ Attitude towards and Access to Oral Healthcare in Heidelberg, Germany: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111559

Kidane YS, Ziegler S, Keck V, Benson-Martin J, Jahn A, Gebresilassie T, Beiersmann C. Eritrean Refugees’ and Asylum-Seekers’ Attitude towards and Access to Oral Healthcare in Heidelberg, Germany: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(21):11559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111559

Chicago/Turabian StyleKidane, Yonas Semere, Sandra Ziegler, Verena Keck, Janine Benson-Martin, Albrecht Jahn, Temesghen Gebresilassie, and Claudia Beiersmann. 2021. "Eritrean Refugees’ and Asylum-Seekers’ Attitude towards and Access to Oral Healthcare in Heidelberg, Germany: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 21: 11559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111559

APA StyleKidane, Y. S., Ziegler, S., Keck, V., Benson-Martin, J., Jahn, A., Gebresilassie, T., & Beiersmann, C. (2021). Eritrean Refugees’ and Asylum-Seekers’ Attitude towards and Access to Oral Healthcare in Heidelberg, Germany: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111559