Internet Use Impact on Physical Health during COVID-19 Lockdown in Bangladesh: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Sampling

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Demographic Variables

2.4. Dependent Variable

2.5. Main Study Factor

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics According to the Frequency of Internet Use among Adults in Bangladesh

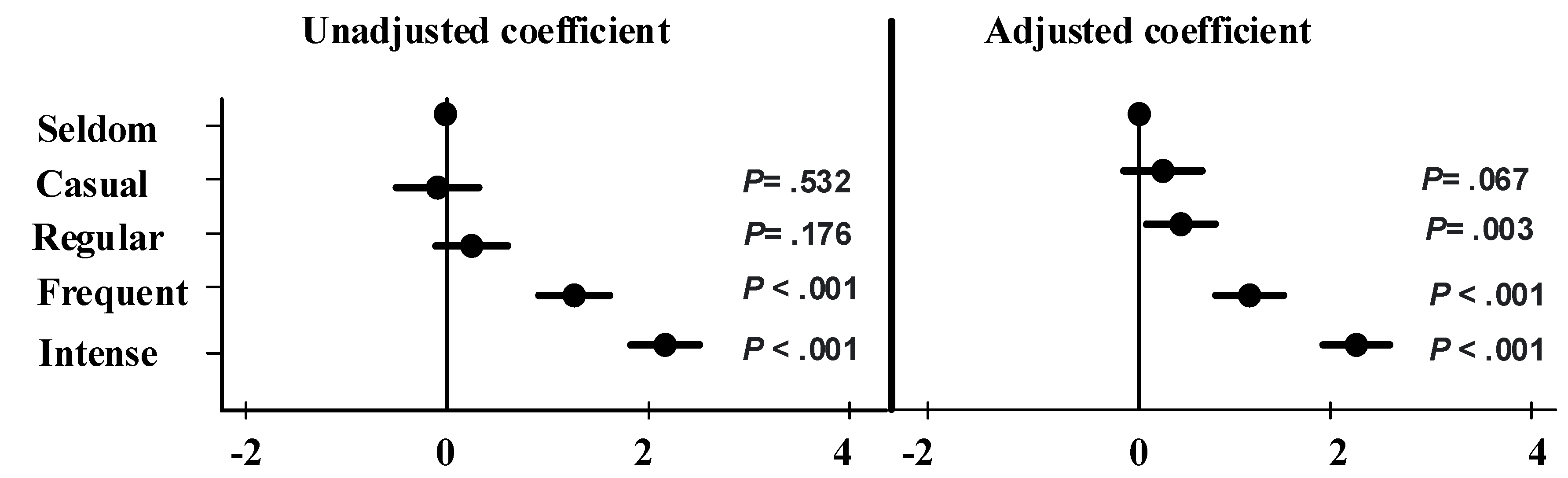

3.2. Unadjusted Analysis for the Association between Prolonged Internet Use and Self-Reported Physical Health Complaints

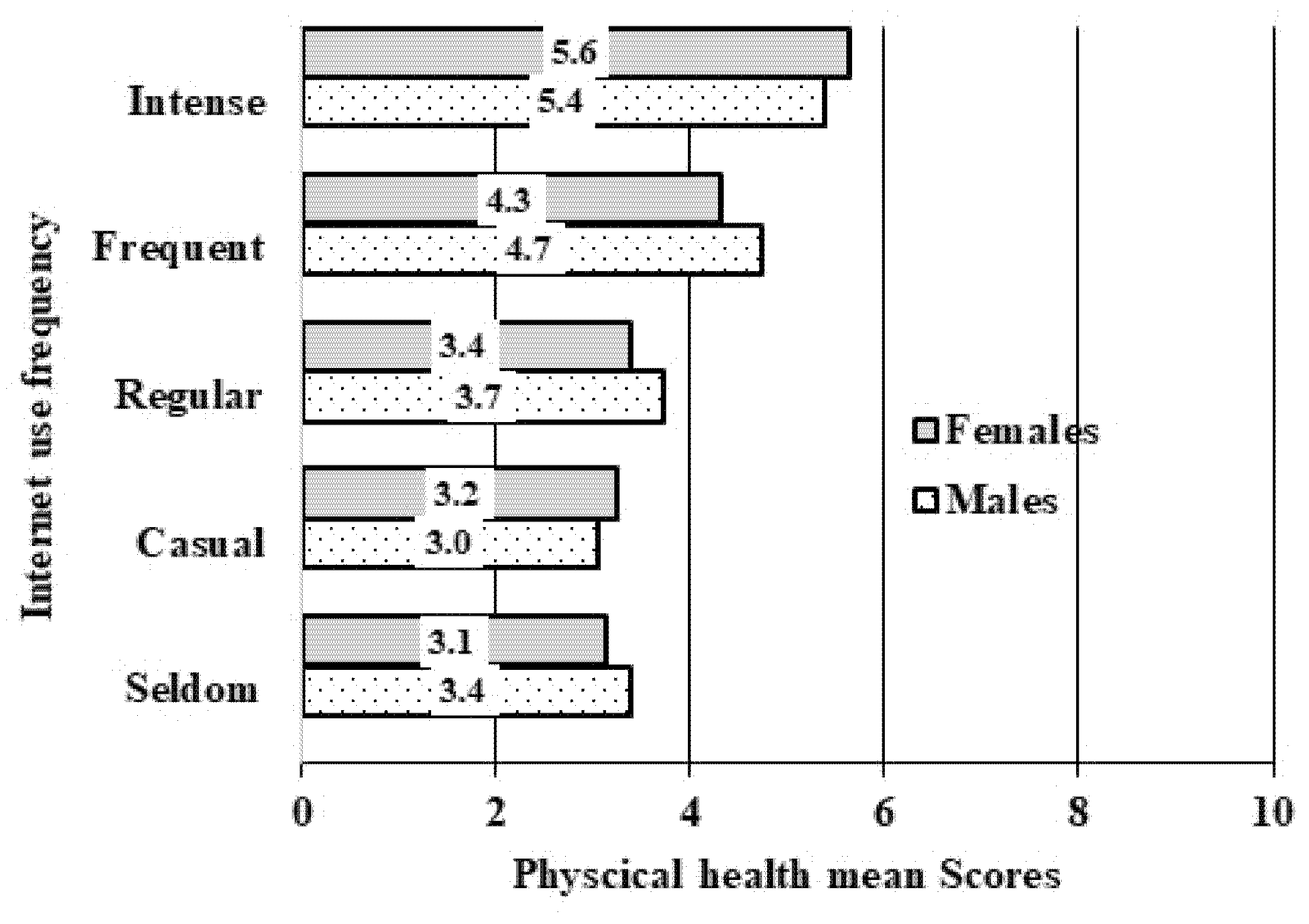

4. The Impact of the Frequency of Internet Use on Physical Health Scores

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De’, R.; Pandey, N.; Pal, A. Impact of digital surge during Covid-19 lockdown: A viewpoint on research and practice. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfin, D.R. Technology as a coping tool during the COVID-19 lockdown: Implications and recommendations. Stress Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawohl, W.; Nordt, C. COVID-19, unemployment, and suicide. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, O.; Potenza, M.N.; Stein, D.J.; King, D.L.; Hodgins, D.C.; Saunders, J.B.; Griffiths, M.D.; Gjoneska, B.; Billieux, J.; Brand, M.; et al. Preventing problematic internet use during COVID-19 lockdown: Consensus guidance. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 100, 152180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Horst, H.A.; Bittanti, M.; Herr Stephenson, B.; Lange, P.G.; Pascoe, C.J.; Robinson, L. Living and Learning with New Media; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keeffe, G.S.; Clarke-Pearson, K. Council on Communications and Media The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Offline consequences of online victimization: School violence and delinquency. J. Sch. Violence 2007, 6, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internet. Available online: http://www.btrc.gov.bd/telco/internet (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Ayyagari, R.; Grover, V.; Purvis, R. Technostress: Technological Antecedents and Implications. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tarafdar, M.; Tu, Q.; Ragu-Nathan, B.S.; Ragu-Nathan, T.S. The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, A. The Zoom Boom: How video calling became a blessing—And a curse. Guardian 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/may/21/the-zoom-boom-how-video-calling-became-a-blessing-and-a-curse (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Osuagwu, U.L.; Miner, C.A.; Bhattarai, D.; Mashige, K.P.; Oloruntoba, R.; Abu, E.K.; Ekpenyong, B.; Chikasirimobi, T.G.; Goson, P.C.; Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G.O.; et al. Misinformation about COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Health Secur. 2021, 19, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Kang, K.-A.; Wang, M.P.; Zhao, S.Z.; Wong, J.Y.H.; O’Connor, S.; Yang, S.C.; Shin, S. Associations between COVID-19 misinformation exposure and belief with COVID-19 knowledge and preventive behaviors: Cross-sectional online study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wei, D.; Li, J.; Zhu, T.; Ning, H. Internet use and its impact on individual physical health. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 5135–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usgaonkar, U.; ShetParkar, S.R.; Shetty, A. Impact of the use of digital devices on eyes during the lockdown period of COVID-19 lockdown. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 69, 1901–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, L.T.; Peng, Z.W.; Mai, J.C.; Jing, J. Faktorerforbundet med internettavhengighetblantungdom. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, C. Age as a variable: Continuous or categorical? Indian J. Psychiatry 2017, 59, 524–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinze, G.; Dunkler, D. Five myths about variable selection. Transpl. Int. 2017, 30, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatcheva, K.P.; Lee, M.; McCormick, J.B.; Rahbar, M.H. Multicollinearity in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 2016, 6, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morrison, C.M.; Gore, H. The relationship between excessive Internet use and depression: A questionnaire-based study of 1319 young people and adults. Psychopathology 2010, 43, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Sun, Y.; Wan, Y.; Hao, J.; Tao, F. Problematic Internet use in Chinese adolescents and its relation to psychosomatic symptoms and life satisfaction. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsai, H.F.; Cheng, S.H.; Yeh, T.L.; Shih, C.C.; Chen, K.C.; Yang, Y.C.; Yang, Y.K. The risk factors of Internet addiction—A survey of university freshmen. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 167, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bravo, A.; García-Azorín, D.; Belvís, R.; González-Oria, C.; Latorre, G.; Santos-Lasaosa, S.; Guerrero-Peral, Á.L. Impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on headache management in Spain: An analysis of the current situation and future perspectives. Neurología 2020, 35, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, I.-H.; Pakpour, A.H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Griffiths, M.D. Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 school hiatus. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servidio, R.; Bartolo, M.G.; Palermiti, A.L.; Costabile, A. Fear of COVID-19, depression, anxiety, and their association with Internet addiction disorder in a sample of Italian students. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 4, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A. Impact of internet addiction on mental health: An integrative therapy is needed. Integr. Med. Int. 2018, 4, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieckiewicz, M.; Danel, D.; Pondel, M.; Smardz, J.; Martynowicz, H.; Wieczorek, T.; Mazur, G.; Pudlo, R.; Wieckiewicz, G. Identification of risk groups for mental disorders, headache and oral behaviors in adults during COVID-19 lockdown. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, K.J.; Gruber, E.M. Psychometric properties of the Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire. Comput. Human Behav. 2010, 26, 1838–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.-F.; Ko, C.-H.; Yen, J.-Y.; Chang, Y.-P.; Cheng, C.-P. Multi-dimensional discriminative factors for Internet addiction among adolescents regarding gender and age: Internet addiction in adolescence. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 63, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.T.; Peng, Z.-W.; Mai, J.-C.; Jing, J. Factors associated with Internet addiction among adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lata, L.N.; Walters, P.; Roitman, S. The politics of gendered space: Social norms and purdah affecting female informal work in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Gend. Work Organ. 2021, 28, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abir, T.; Kalimullah, N.A.; Osuagwu, U.L.; Nur-A Yazdani, D.M.; Husain, T.; Goson, P.C.; Basak, P.; Rahman, M.A.; Al Mamun, A.; Permarupan, P.Y.; et al. Prevalence and factors associated with mental health impact of COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A survey-based cross-sectional study. Ann. Glob. Health 2021, 87, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Sujan, M.S.H.; Tasnim, R.; Ferdous, M.Z.; Masud, J.H.B.; Kundu, S.; Mosaddek, A.S.M.; Choudhuri, M.S.K.; Kircaburun, K.; Griffiths, M.D. Problematic internet use among young and adult population in Bangladesh: Correlates with lifestyle and online activities during COVID-19 lockdown. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2020, 12, 100311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ko, N.-Y.; Lu, W.-H.; Chen, Y.-L.; Li, D.-J.; Wang, P.-W.; Hsu, S.-T.; Chen, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-H.; Chang, Y.-P.; Yen, C.-F. COVID-19-related information sources and psychological well-being: An online survey study in Taiwan. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, M.; Black, D.W. Internet addiction: Definition, assessment, epidemiology and clinical management. CNS Drugs 2008, 22, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. 2021. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f334423054. (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- Knief, U.; Forstmeier, W. Violating the normality assumption may be the lesser of two evils. Behav. Res. Methods 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total (N = 3236) | Intense (n = 1668) | Frequent (n = 689) | Regular (n = 559) | Casual (n = 187) | Seldom (n = 93) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demography | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1976 (61.1) | 1179 (70.7) | 382 (55.4) | 264 (44.1) | 93 (44.7) | 58 (62.4) |

| Female | 1260 (38.9) | 489 (29.3) | 307 (44.6) | 335 (55.9) | 94 (50.3) | 35 (37.6) |

| Age in years | ||||||

| 18–27 | 555 (17.2) | 30 (1.8) | 156 (22.6) | 254 (42.1) | 98 (52.4) | 17 (17.9) |

| 28–37 | 1657 (51.1) | 956 (57.3) | 366 (53.1) | 238 (39.5) | 60 (32.1) | 37 (39.0) |

| 38+ | 1030 (31.8) | 682 (40.9) | 167 (24.2) | 111 (18.4) | 29 (15.5) | 41 (43.2) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 508 (15.7) | 29 (1.7) | 150 (21.8) | 223(37.0) | 90 (48.1) | 16 (16.8) |

| Married | 2632 (81.2) | 1632 (97.8) | 505 (73.3) | 339(56.2) | 83 (44.40) | 73 (76.8) |

| Divorced/widow | 102 (3.1) | 7 (0.4) | 34 (4.9) | 41 (6.8) | 14 (7.49) | 6 (6.3) |

| Place of residence (%) | ||||||

| Barisal Division | 172 (5.31) | 70 (4.20) | 48 (7.0) | 35 (5.0) | 7 (3.7) | 12 (12.6) |

| Chittagong Division | 291 (9.0) | 100 (6) | 107 (15.5) | 61 (10.1) | 16 (8.6) | 7 (7.4) |

| Dhaka Division | 1574 (48.6) | 1010 (60.6) | 205 (29.8) | 236 (39.1) | 95 (50.8) | 28 (29.5) |

| Khulna Division | 352 (10.9) | 115 (6.9) | 109 (15.8) | 92 (15.3) | 20 (10.7) | 16 (16.8) |

| Mymensingh Division | 313 (9.7) | 127 (7.6) | 76 (11.0) | 85 (14.1) | 17 (9.1) | 8 (8.4) |

| Rajshahi Division | 213 (6.6) | 99 (5.9) | 47 (6.8) | 41 (6.8) | 18 (9.6) | 8 (8.4) |

| Rangpur Division | 179 (5.5) | 93 (5.6) | 45 (6.5) | 22 (3.7) | 9 (4.8) | 10 (10.5) |

| Sylhet Division | 148 (4.6) | 54 (3.2) | 52 (7.6) | 31 (5.1) | 5 (2.7) | 6 (6.3) |

| Mother’s Level of Education | ||||||

| Higher education (above Bachelor) | 1287 (39.7) | 684 (41.0) | 341 (49.5) | 178 (29.5) | 46 (24.6) | 38 (40.) |

| 1514 (46.7) | 961 (57.6) | 226 (32.8) | 233 (38.6) | 67 (35.8) | 27 (28.4) | |

| Intermediate (11–12) | 441 (13.6) | 23 (1.4) | 122 (17.7) | 192 (31.84) | 74 (39.5) | 30 (31.6) |

| Working status | ||||||

| Employed | 2864 (88.3) | 1647 (98.7) | 600 (87.1) | 432 (71.6) | 99 (52.9) | 86 (91.0) |

| Not employed/student | 378 (11.7) | 21 (1.3) | 89 (12.9) | 171 (28.4) | 88 (47.1) | 9 (9.47) |

| Income in Taka | ||||||

| Lower-income (<30,000) | 204 (6.3) | 14 (0.9) | 37 (5.4) | 102 (16.9) | 41 (21.9) | 10 (10.4) |

| Middle-income (30,000–70,000) | 1496 (46.1) | 510 (30.9) | 433 (62.8) | 389 (64.5) | 108 (57.8) | 56 (59.0) |

| High-income (>70,000) | 1542 (47.7) | 1144 (68.59) | 219 (31.8) | 112 (18.8) | 38 (20.3) | 29 (30.5) |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Healthcare workers | 675 (20.8) | 31 (1.9) | 212 (30.8) | 304 (50.4) | 89 (47.6) | 39 (41.1) |

| Non-healthcare worker | 2567 (79.2) | 1637 (98.1) | 477 (69.2) | 299 (49.6) | 98 (52.4) | 56 (59.0) |

| Physical Complaints | n | Prevalence (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Male | Female | ||

| Back pain | 2261 | 69.9 [68.27, 71.43] | 78.14 [76.26, 79.91] | 56.90 [54.15, 59.62] |

| Finger numbness | 2106 | 65.10 [63.42, 66.71] | 72.37 [70.35, 74.30] | 53.65 [50.89, 56.39] |

| Headaches | 2346 | 72.50 [70.93, 74.01] | 78.80 [76.94, 80.54] | 62.62 [59.91, 65.25] |

| Inability to sleep | 1396 | 43.14 [41.44, 44.85] | 41.95 [39.79, 44.14] | 45.00 [42.27, 47.76] |

| Poor Nutrition | 746 | 23.05 [21.63, 24.54] | 16.55 [14.97, 18.25] | 33.25 [30.70, 35.91] |

| Poor Personal Hygiene | 605 | 18.70 [17.39, 20.08] | 14.98 [13.47, 16.62] | 24.52 [22.23, 26.98] |

| Neck pain | 1789 | 55.28 [53.56, 56.99] | 58.50 [56.31, 60.66] | 50.24 [47.48, 53.00] |

| Dry eyes/other vision problems | 1815 | 56.09 [54.37, 57.79] | 57.54 [55.35, 59.70] | 53.81 [51.05, 56.55] |

| Weight gain/loss | 1653 | 51.08 [49.36, 52.80] | 52.43 [50.22, 54.63] | 48.97 [46.21, 51.73] |

| Loss of Appetite | 499 | 15.42 [14.22, 16.71] | 13.77 [12.31, 15.36] | 18.02 [15.99, 20.24] |

| Variables | Mean Scores (SD) | Unadjusted Coefficient [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 4.85 (1.83) *** | Reference |

| Female | 4.47 (1.88) | −0.38 [−0.51, −0.25] |

| Age | ||

| 18–27 yrs | 3.52 (1.71) *** | Reference |

| 28–37 yrs | 5.02 (1.81) | 1.50 [1.33, 1.67] |

| 38+ yrs | 4.80 (1.77) | 1.31 [1.12, 1.49] |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 3.67 (1.76) *** | Reference |

| Married | 4.96 (1.79) | 1.30 [1.13, 1.47] |

| Divorced/widow | 3.00 (1.19) | −0.67 [−1.04, −0.29] |

| Place of residence | ||

| Barisal Division | 5.35 (1.83) *** | Reference |

| Chittagong Division | 4.66 (1.87) | −0.69 [−1.04, −0.35] |

| Dhaka Division | 4.36 (1.77) | −0.99 [−1.28, −0.70] |

| Khulna Division | 4.83 (1.83) | −0.52 [−0.85, −0.19] |

| Mymensingh Division | 5.03 (1.92) | −0.32 [−0.66, 0.02] |

| Rajshahi Division | 5.21 (1.91) | −0.14 [−0.51, 0.22] |

| Rangpur Division | 5.47 (1.88) | 0.12 [−0.26, 0.50] |

| Sylhet Division | 4.99 (1.83) | −0.36 [−0.76, 0.04] |

| Mother’s Level of Education | ||

| Higher education | 4.71 (1.82) *** | Reference |

| Bachelor | 5.00 (1.87) | 0.30 [0.16, 0.43] |

| Intermediate (11–12) | 3.65 (1.50) | −1.06 [−1.26, −0.86] |

| Working status | ||

| Employed | 4.89 (1.79) *** | Reference |

| Not employed/student | 3.24 (1.72) | −1.65 [−1.84, −1.46] |

| Income in Taka | ||

| Lower-income (<30,000) | 3.05 (1.50) *** | Reference |

| Middle-income (30,000) | 4.82 (1.88) | 1.77 [1.51, 2.04] |

| High-income (>70,000) | 4.80 (1.77) | 1.75 [1.48, 2.01] |

| Occupation | ||

| Healthcare workers | 3.62 (1.26) *** | Reference |

| Non-healthcare workers | 4.98 (1.89) | 1.36 [1.21, 1.51] |

| Variables | Adjusted Coefficients [95% CI] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | Reference | |

| Female | −0.08 [−0.20, 0.04] | 0.179 |

| Age groups | ||

| 18–27 yrs | Reference | |

| 28–37 yrs | 0.09 [−0.13, 0.30] | 0.440 |

| 38+ yrs | −0.03 [−0.29, 0.23] | 0.818 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | Reference | |

| Married | −0.08 [−0.29, 0.12] | 0.431 |

| Divorced/widow | −1.09 [−1.44, −0.74] | <0.0005 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Barisal Division | Reference | |

| Chittagong Division | −0.70 [−0.99, −0.41] | <0.0005 |

| Dhaka Division | −1.27 [−1.51, −1.02] | <0.0005 |

| Khulna Division | −0.42 [−0.70, −0.14] | 0.003 |

| Mymensingh Division | −0.31 [−0.59, −0.03] | 0.031 |

| Rajshahi Division | −0.29 [−0.60, 0.01] | 0.060 |

| Rangpur Division | −0.11 [−0.43, 0.21] | 0.487 |

| Sylhet Division | −0.40 [−0.74, −0.07] | 0.018 |

| Mother’s Level of Education | ||

| Higher education | Reference | |

| Bachelor | −0.00 [−0.16, 0.16] | 0.976 |

| Intermediate (11–12) | 0.01 [−0.19, 0.21] | 0.924 |

| Working status | ||

| Employed | Reference | |

| Not employed/student | −0.49 [−0.72, −0.26] | <0.0005 |

| Income in Taka | ||

| Lower-income (<30,000) | Reference | |

| Middle-income (30,000–70,000) | 0.72 [0.48, 0.96] | <0.0005 |

| High-income (>70,000) | 0.26 [−0.00, 0.53] | 0.052 |

| Occupation | ||

| Healthcare workers | Reference | |

| Non-health care worker | 0.62 [0.47, 0.78] | <0.0005 |

| Internet use Frequency | ||

| Seldom | Reference | - |

| Casual | 0.36 [−0.02, 0.74] | 0.067 |

| Regular | 0.52 [0.18, 0.85] | 0.003 |

| Frequent | 1.21 [0.88, 1.54] | <0.0005 |

| Intense | 2.24 [1.91, 2.57] | <0.0005 |

| Constant | 3.18 [2.69, 3.67] | <0.0005 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abir, T.; Osuagwu, U.L.; Nur-A Yazdani, D.M.; Mamun, A.A.; Kakon, K.; Salamah, A.A.; Zainol, N.R.; Khanam, M.; Agho, K.E. Internet Use Impact on Physical Health during COVID-19 Lockdown in Bangladesh: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010728

Abir T, Osuagwu UL, Nur-A Yazdani DM, Mamun AA, Kakon K, Salamah AA, Zainol NR, Khanam M, Agho KE. Internet Use Impact on Physical Health during COVID-19 Lockdown in Bangladesh: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(20):10728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010728

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbir, Tanvir, Uchechukwu Levi Osuagwu, Dewan Muhammad Nur-A Yazdani, Abdullah Al Mamun, Kaniz Kakon, Anas A. Salamah, Noor Raihani Zainol, Mansura Khanam, and Kingsley Emwinyore Agho. 2021. "Internet Use Impact on Physical Health during COVID-19 Lockdown in Bangladesh: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 20: 10728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010728

APA StyleAbir, T., Osuagwu, U. L., Nur-A Yazdani, D. M., Mamun, A. A., Kakon, K., Salamah, A. A., Zainol, N. R., Khanam, M., & Agho, K. E. (2021). Internet Use Impact on Physical Health during COVID-19 Lockdown in Bangladesh: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 10728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010728