Development of a Binational Framework for Active and Healthy Ageing (AHA) Bridging Austria and Slovenia in a Thermal Spa Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sampling

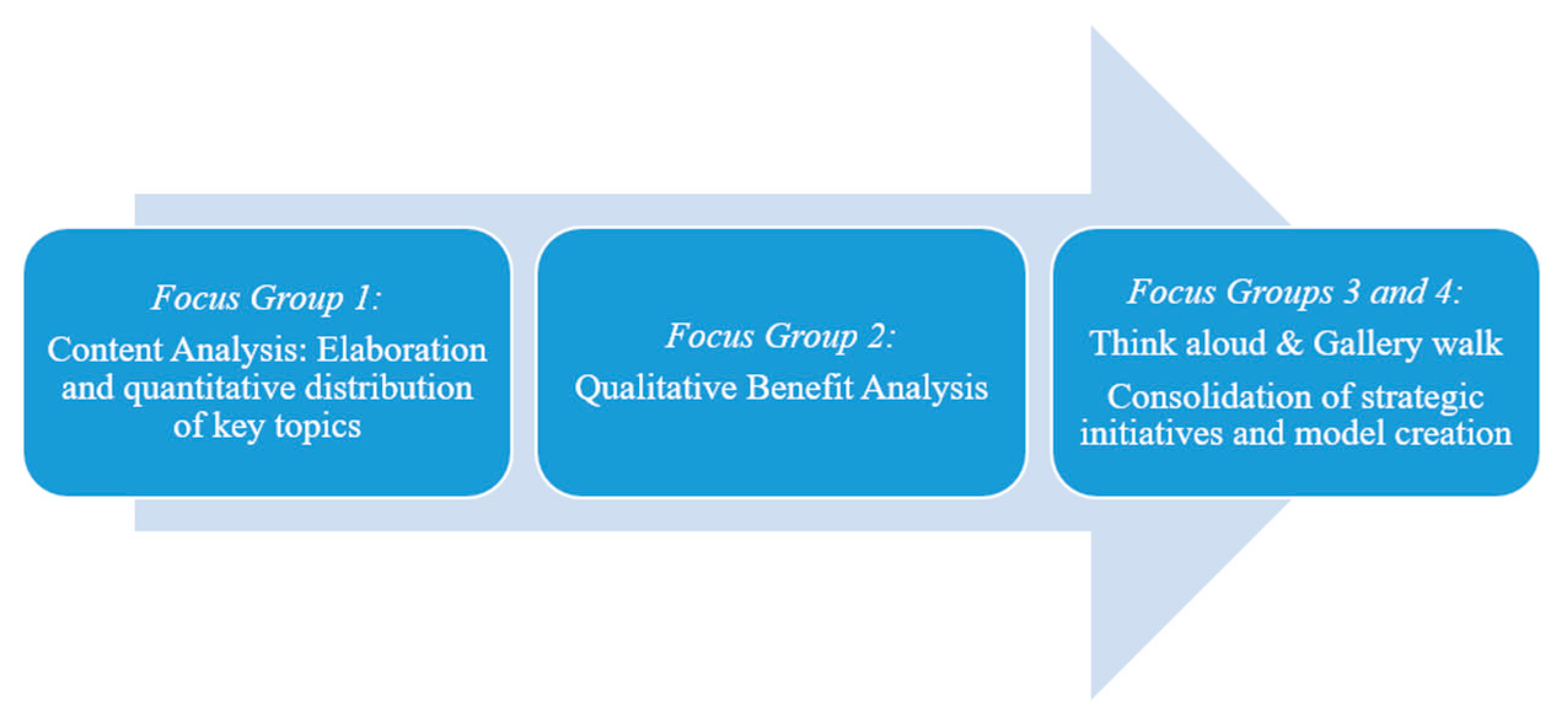

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

2.4. Ensuring Rigor

3. Results

3.1. First Stage Results—Strategic Key Assets

- Ageing

- Education and Training

- Networking/Organization/Business development

- Medical Care

- Living arrangements/Housing development

- Health tourism

- Prevention and Health promotion

- Nature/Experience of nature

- Outdoor-sports

- Food and Nutrition

- Mobility

- Complementary Medicine

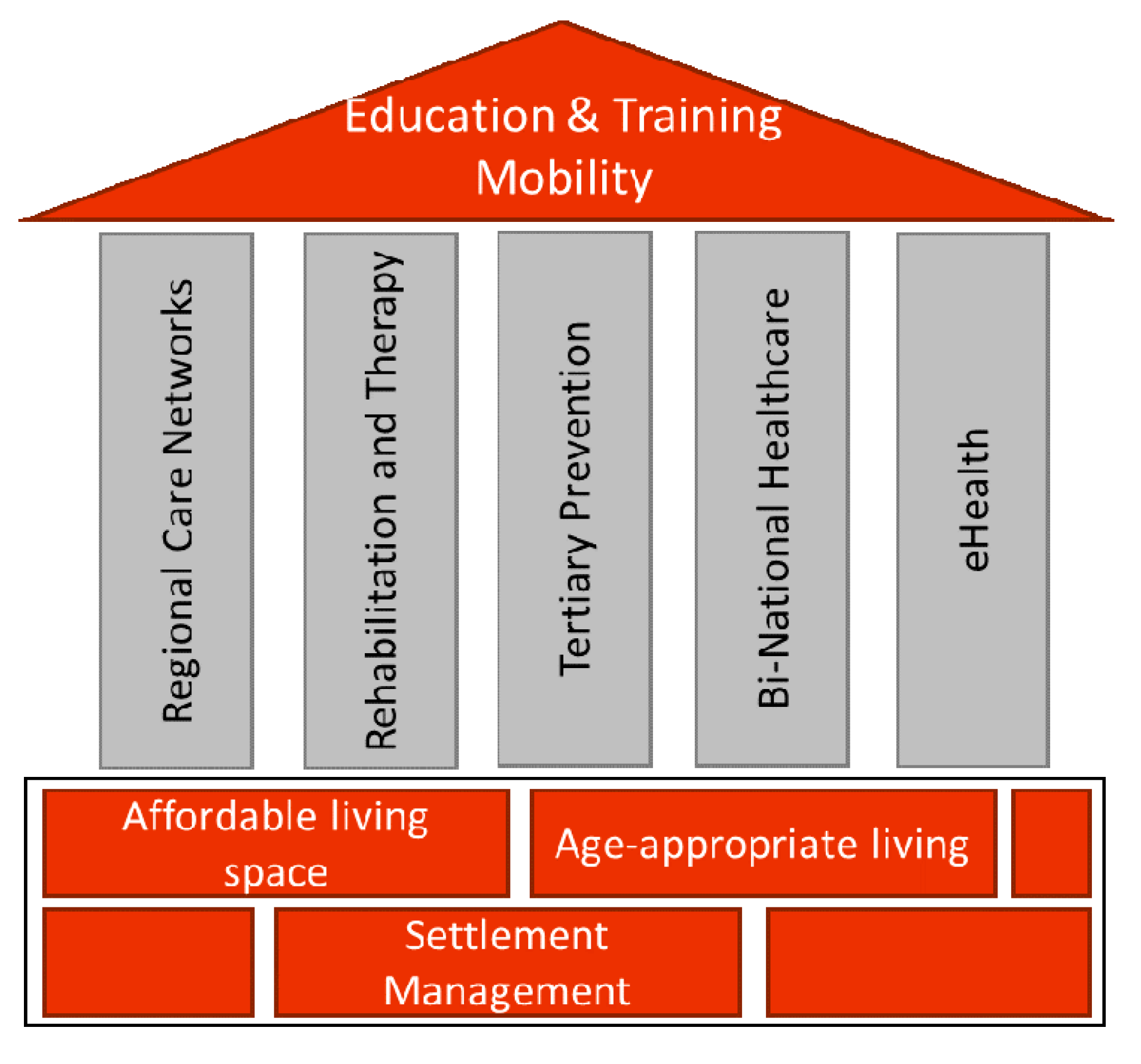

3.2. Second Stage Results—Developing a Framework Model for the Cross-Border Region Promura

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Impact of Demographic Change; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Albreht, T.; Delnoij, D.M.J.; Klazinga, N. Changes in primary health care centres over the transition period in Slovenia. Eur. J. Public Health 2006, 16, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooperation Programme Interreg V-A Slovenia-Austria. Cooperation Programme Interreg V-A Slovenia-Austria, Version 1.2; Government Office of the Republic of Slovenia for Development and European Cohesion Policy: Maribor, Slovenia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Territorial Cooperation in Europe. A Historical Perspective; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing. What is the European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing (EIP on AHA)? Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eip/ageing/about-the-partnership_en (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing. Age-Friendly Tourism; EIP on AHA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy and Action Plan on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sixsmith, J.; Fang, M.L.; Woolrych, R.; Canham, S.L.; Battersby, L.; Sixsmith, A. Ageing well in the right place: Partnership working with older people. Work. Older People 2017, 21, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramm, J.M.; Van Dijk, H.M.; Nieboer, A.P. The creation of age-friendly environments is especially important to frail older people. Ageing Soc. 2018, 38, 700–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrmann, M.; Lindner, S.; Hofer-Fischanger, K.; Rehb, R.; Pechstädt, K.; Wiedenhofer, R.; Schwarze, G.; Adamer-König, E.-M.; Mischak, R.; Pfeiffer, K.P.; et al. Strategy for Deployment of Integrated Healthy Aging Regions Based Upon an Evidence-Based Regional Ecosystem—The Styria Model [Original Research]. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 510475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. My Region, My Europe, Our Future. Seventh Report on Economic, Social and Territorial Cohesion; Publication Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Land Steiermark. Landesstatistik [German]; Land Steiermark: Graz, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. Murska Sobota. Available online: https://www.citypopulation.de/de/slovenia/pomurska/murska_sobota/080006__murska_sobota/ (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Thermen & Vulkanland Steiermark. Das Unternehmen & Das Team. [German]. Available online: https://www.thermen-vulkanland.at/de/b2b/Das-Unternehmen (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Slowenische Touristenorganisation. Thermen und Heilbäder. [German]. Available online: https://www.slovenia.info/de/aktivitaten/thermen-und-heilbader (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Amt der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung Abteilung 12 Wirtschaft Tourismus Sport. Wirtschafts und Tourismusstrategie Steiermark 2015. Wachstum durch Innovation; Amt der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung Abteilung 12 Wirtschaft Tourismus Sport: Graz, Austria, 2015. (In Germany) [Google Scholar]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B. Review of community-based research: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, H.J.; Chief, C.; Jiménez, D.; Begay, A.; Milner, T.F.; Sullivan, S.; Torres, E.; Remiker, M.; Longorio, A.E.S.; Sabo, S.; et al. Voices of Community Partners: Perspectives Gained from Conversations of Community-Based Participatory Research Experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altrichter, H.; Kemmis, S.; McTaggart, R.; Zuber-Skerritt, O. The concept of action research. Learn. Organ. 2002, 9, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozanne, J.L.; Anderson, L. Community Action Research. J. Public Policy Mark. 2010, 29, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landesvereinigung für Gesundheit und Akademie für Sozialmedizin Niedersachsen e.V. Gesundheitsregionen in Deutschland; Landesvereinigung für Gesundheit und Akademie für Sozialmedizin Niedersachsen e.V.: Hannover, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyssou, D.; Marchant, T.; Pirlot, M.; Perny, P.; Tsoukiàs, A.; Vincke, P. Assessing Competing Projects: The Example of Cost-Benefit Analysis. In Evaluation and Decision Models: A Critical Perspective; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Van Someren, M.; Barnard, Y.; Sandberg, J. The think aloud method. In A Practical Guide to Modelling Cognitive Processes; Academic Press: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In Grundlagen und Techniken, 11th ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rodenbaugh, D.W. Maximize a team-based learning gallery walk experience: Herding cats is easier than you think. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2015, 39, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lincoln, Y.; Guba, E. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.M.; Barrett, M.; Mayan, M.; Olson, K.; Spiers, J. Verification Strategies for Establishing Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2002, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyumba, T.O.; Wilson, K.; Derrick, C.J.; Mukherjee, N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, J.; Teller, A.; Erhard, M.; Liquete, C.; Braat, L.; Berry, P.M.; Egoh, B.N.; Puydarrieux, P.; Fiorina, C.; Santos-Martin, F.; et al. Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and Their Services. An Analytical Framework for Ecosystem Assessments under Action 5 of the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, K.J.; Schüz, B. Psychosocial factors in healthy ageing. Psychol. Health 2015, 30, 607–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusdal, A.K.; Johansson-Pajala, R.-M.; Zander, V.; Wågert, P.V.H. Prerequisites for a healthy and independent life among older people: A Delphi study. Ageing Soc. 2020, 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, G. Collaboration and Co-Creation. New Platforms for Marketing and Innovation; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Copernicus. Ecosystems of Europe. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/news/ecosystems-of-europe (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Vega-Vázquez, M.; Rodríguez-Serrano, M.Á.; Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Oviedo-García, M.Á. The impact of tourism on active and healthy ageing: Health-related quality of life. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2020, 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, J.; Sanz, M.; Ferrandis, E.; McCabe, S.; García, J.S. Social Tourism and Healthy Ageing. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 18, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campón-Cerro, A.; Di-Clemente, E.; Mogollón, J.M.; Folgado-Fernández, J.A. Healthy Water-Based Tourism Experiences: Their Contribution to Quality of Life, Satisfaction and Loyalty. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. The EU Helps Reboot Europe’s Tourism. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-travel-eu/health/coronavirus-response/travel-during-coronavirus-pandemic/eu-helps-reboot-europes-tourism_en (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- World Tourism Organization. UNWTO Recommendations on Tourism and Rural Development; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union—Part three: Union policies and internal actions—Title XIV: Public health—Article 168 (ex Article 152 TEC). 2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A12008E168 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- European Commission. Study on Cross-Border Cooperation. Capitalising on Existing Initiatives for Cooperation in Cross-Border Regions; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nienaber, B.; Wille, C. Cross-border cooperation in Europe: A relational perspective. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomski, P. COVID-19: From temporary de-globalisation to a re-discovery of tourism? Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Regions and Innovation: Collaborating across Borders. OECD Reviews of Regional Innovation; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, G.; Timonen, V. Using Grounded Theory Method to Capture and Analyze Health Care Experiences. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 50, 1195–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre for Social Justice and Community Action—Durham University. Community-Based Participatory Research: Ethical Challenges; Durham University: Durham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lindner, S.; Illing, K.; Sommer, J.; Krajnc-Nikolić, T.; Harer, J.; Kurre, C.; Lautner, K.; Hauser, M.; Grabar, D.; Graf-Stelzl, R.; et al. Development of a Binational Framework for Active and Healthy Ageing (AHA) Bridging Austria and Slovenia in a Thermal Spa Region. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020639

Lindner S, Illing K, Sommer J, Krajnc-Nikolić T, Harer J, Kurre C, Lautner K, Hauser M, Grabar D, Graf-Stelzl R, et al. Development of a Binational Framework for Active and Healthy Ageing (AHA) Bridging Austria and Slovenia in a Thermal Spa Region. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):639. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020639

Chicago/Turabian StyleLindner, Sonja, Kai Illing, Josef Sommer, Tatjana Krajnc-Nikolić, Johann Harer, Christoph Kurre, Karl Lautner, Mateja Hauser, Daniel Grabar, Robert Graf-Stelzl, and et al. 2021. "Development of a Binational Framework for Active and Healthy Ageing (AHA) Bridging Austria and Slovenia in a Thermal Spa Region" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 2: 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020639

APA StyleLindner, S., Illing, K., Sommer, J., Krajnc-Nikolić, T., Harer, J., Kurre, C., Lautner, K., Hauser, M., Grabar, D., Graf-Stelzl, R., Korn, C., Pilz, K., Ritter, B., & Roller-Wirnsberger, R. (2021). Development of a Binational Framework for Active and Healthy Ageing (AHA) Bridging Austria and Slovenia in a Thermal Spa Region. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 639. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020639