Adverse Birth Outcomes Due to Exposure to Household Air Pollution from Unclean Cooking Fuel among Women of Reproductive Age in Nigeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

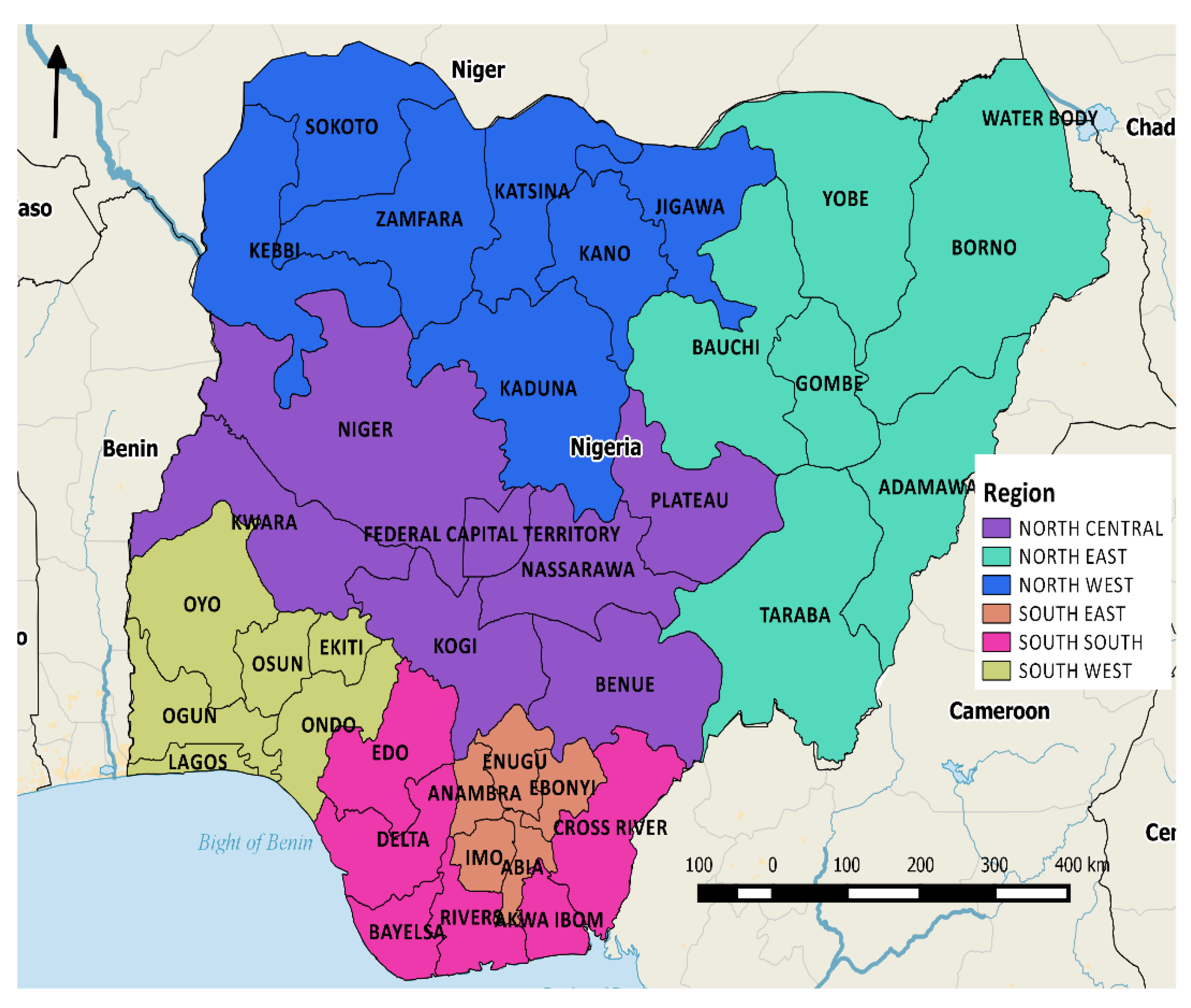

2.1. Data Source, Setting, and Variables

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

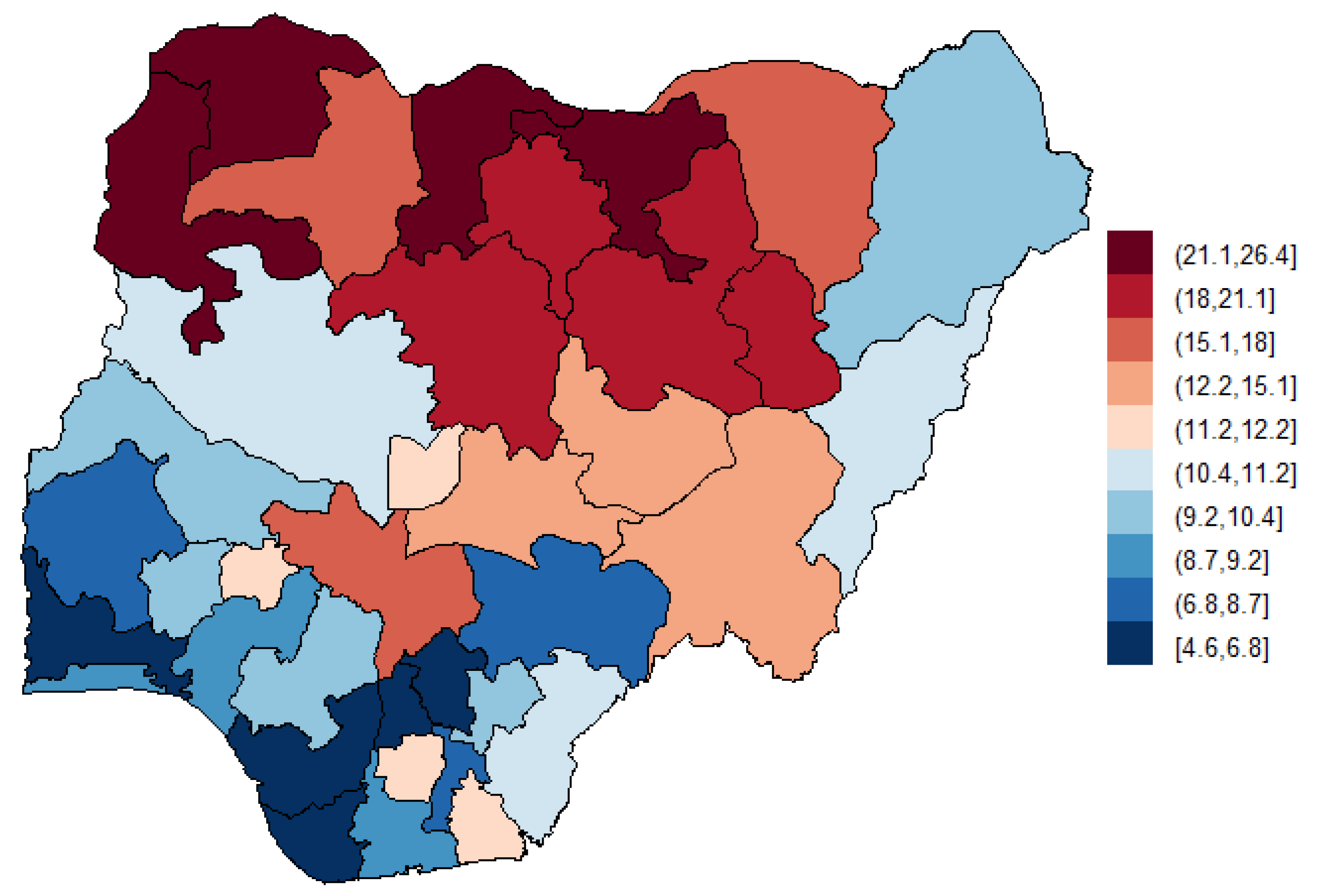

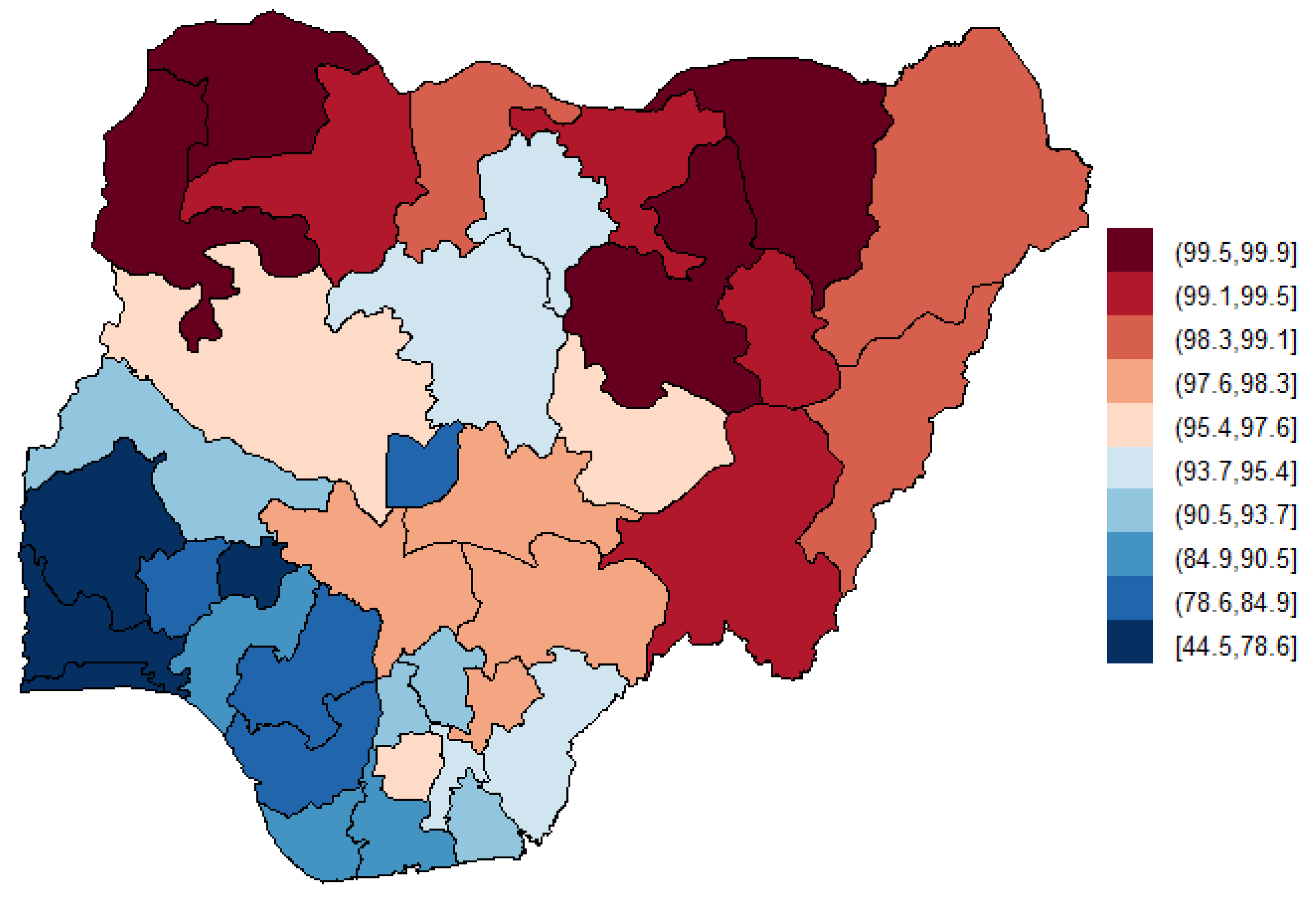

3.1. Descriptive Summaries

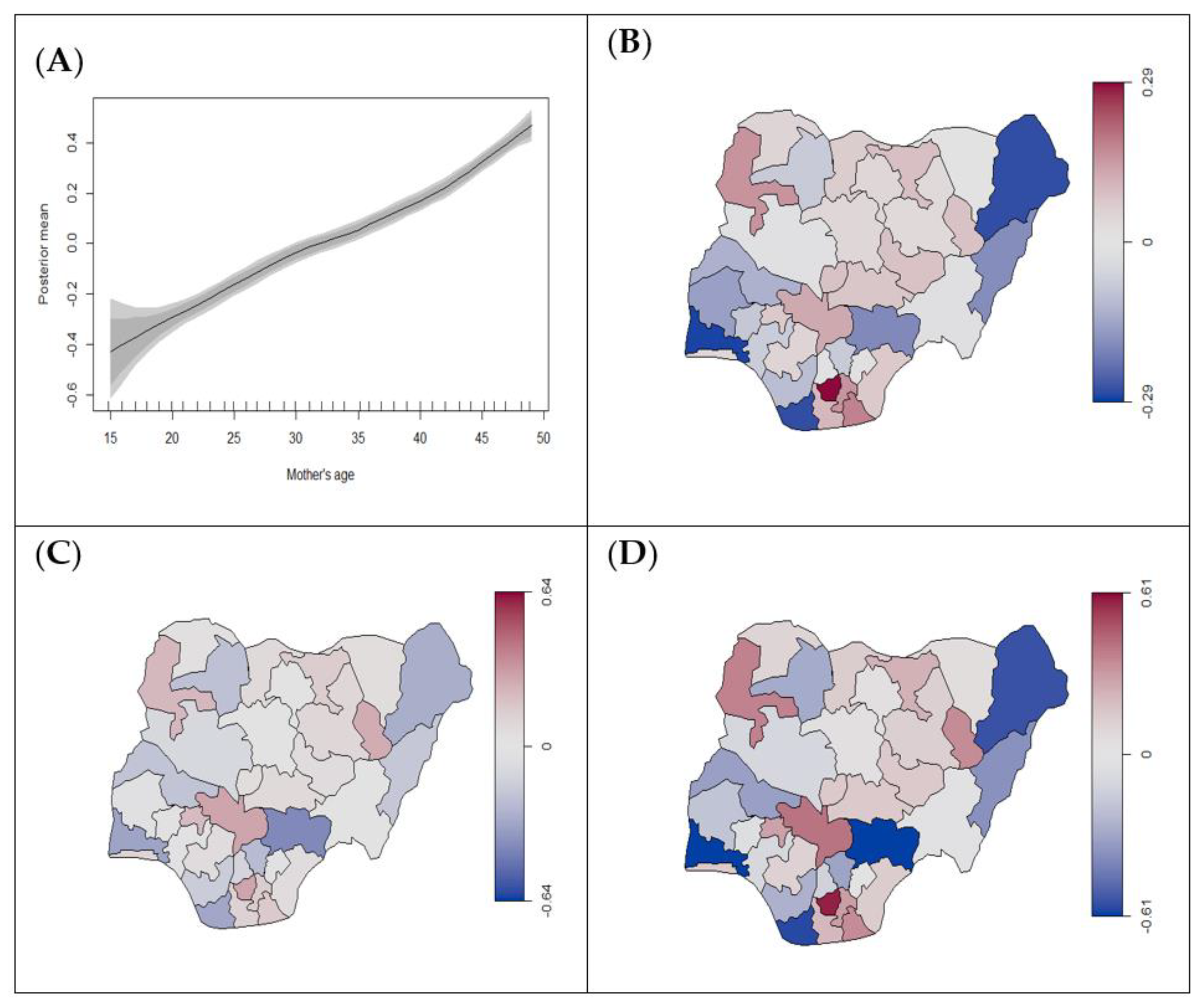

3.2. Association between HAP Exposure and Adverse Birth Outcomes

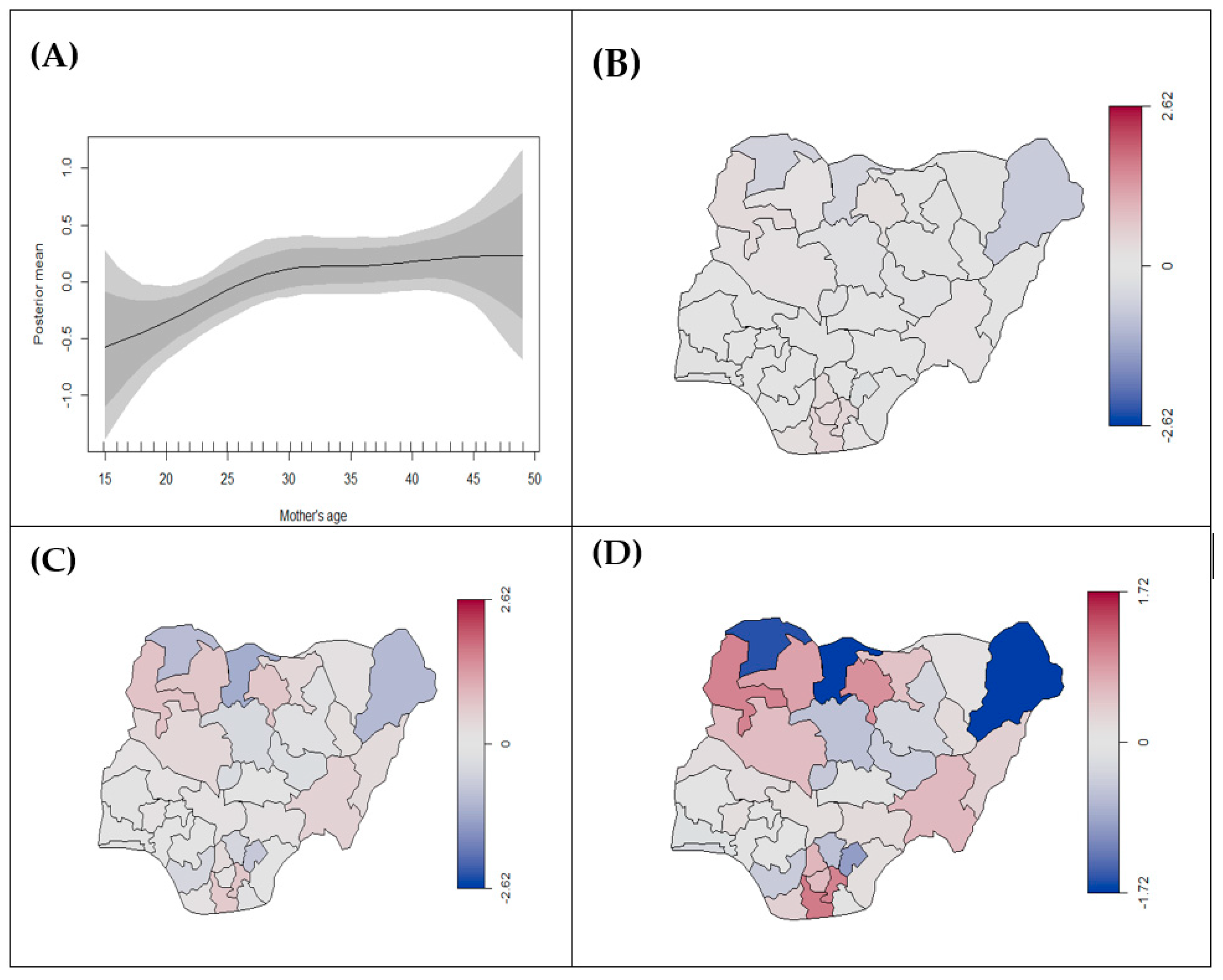

3.2.1. Prevalence of Stillbirth

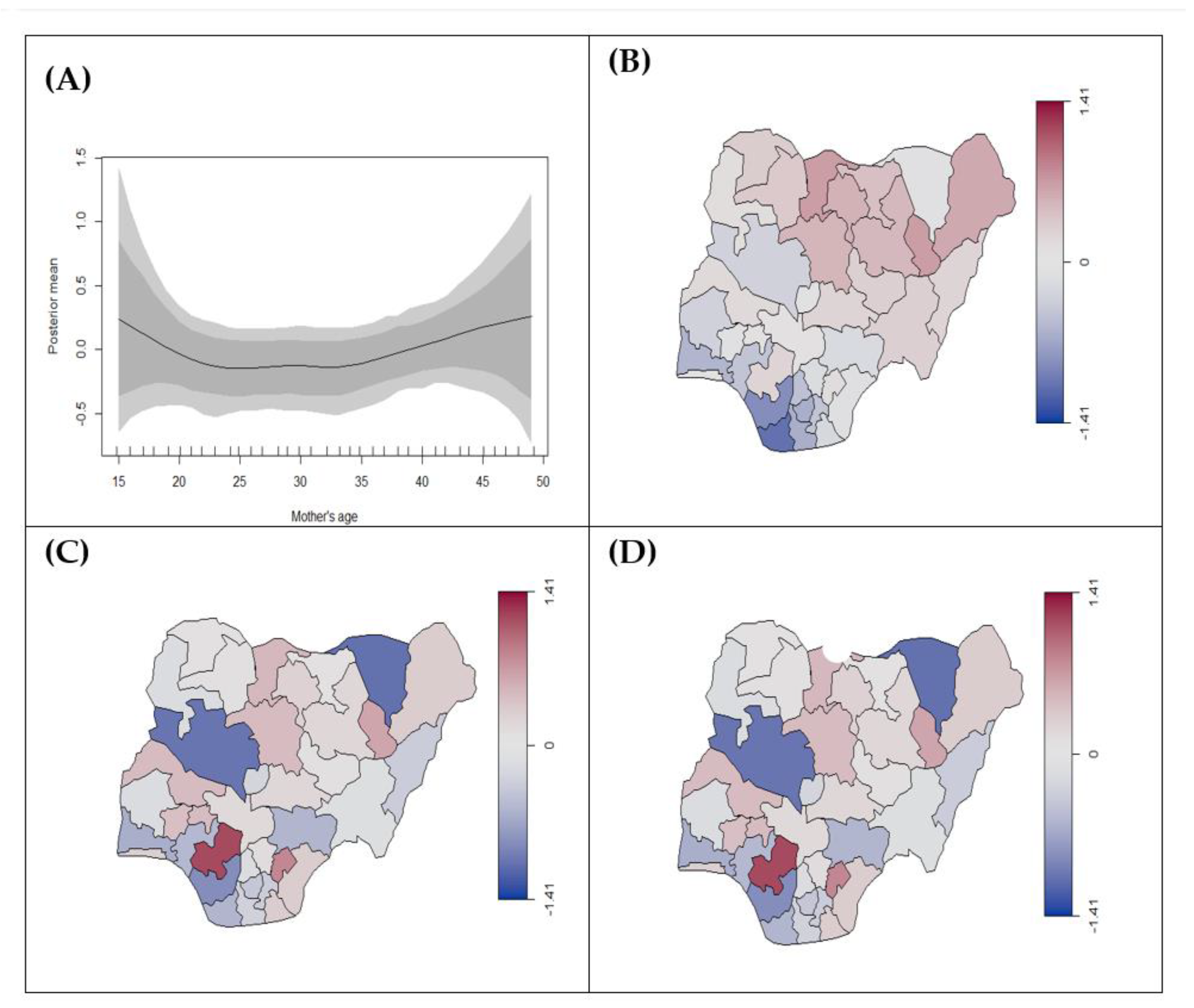

3.2.2. Birth Weight (Low Birth Weight vs. Normal Weight)

3.2.3. Duration of Pregnancy (Preterm vs. Term Birth)

3.3. Predictors of Adverse Birth Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHA Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Low Birth Weight Policy Brief; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Ballot, D.E.; Chirwa, T.F.; Cooper, P.A. Determinants of survival in very low birth weight neonates in a public sector hospital in Johannesburg. BMC Pediatrics 2010, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlui, M.; Azahar, N.; Oche, O.M.; Aziz, N.A. Risk factors for low birth weight in Nigeria: Evidence from the 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey. Glob. Health Action 2016, 9, 28822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawn, J.E.P.; Blencowe, H.M.; Waiswa, P.P.; Amouzou, A.P.; Mathers, C.P.; Hogan, D.P.; Flenady, V.P.; Frøen, J.F.P.; Qureshi, Z.U.B.M.; Calderwood, C.B.M.; et al. Stillbirths: Rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancetthe 2016, 387, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Household Air Pollution—The World’s Leading Environmental Health Risk; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory Data: Mortality from Household Air Pollution; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- World Health Organization. Household Air Pollution and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Lakshmi, P.V.M.; Virdi, N.K.; Thakur, J.S.; Smith, K.R.; Bates, M.N.; Kumar, R. Biomass fuel and risk of tuberculosis: A case–control study from Northern India. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2012, 66, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, S.; Yamamoto, S. Effect of Indoor air pollution from biomass and solid fuel combustion on symptoms of preeclampsia/eclampsia in Indian women. Indoor Air 2015, 25, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravilla, T.D.; Gupta, S.; Ravindran, R.D.; Vashist, P.; Krishnan, T.; Maraini, G.; Chakravarthy, U.; Fletcher, A.E. Use of cooking fuels and cataract in a population-based study: The India eye disease study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1857–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, K.L.; Arku, R.E.; Hughes, A.F.; Vallarino, J.; Carmichael, H.; Spengler, J.D.; Agyei-Mensah, S.; Ezzati, M. Air Pollution in Accra Neighborhoods: Spatial, Socioeconomic, and Temporal Patterns. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 2270–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, E.L.; Dreibelbis, R.; Klasen, E.; Naithani, N.; Baliddawa, J.; Menya, D.; Khatry, S.; Levy, S.; Tielsch, J.M.; Miranda, J.J. Behavioral attitudes and preferences in cooking practices with traditional open-fire stoves in Peru, Nepal, and Kenya: Implications for improved cookstove interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 10310–10326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedinmyer, C.; Dickinson, K.; Piedrahita, R.; Kanyomse, E.; Coffey, E.; Hannigan, M.; Alirigia, R.; Oduro, A. Rural–urban differences in cooking practices and exposures in Northern Ghana. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 065009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyeh, A.K.; Kukula, V.; Odonkor, G.; Rosemond Akepene, E.; Adjei, A.; Solomon, N.-B.; Akpakli, D.E.; Gyapong, M. Socioeconomic and demographic determinants of birth weight in southern rural Ghana: Evidence from Dodowa Health and Demographic Surveillance System. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquia, M.L.; Urquia, M.L.; Frank, J.W.; Frank, J.W.; Alazraqui, M.; Alazraqui, M.; Guevel, C.; Guevel, C.; Spinelli, H.G.; Spinelli, H.G. Contrasting socioeconomic gradients in small for gestational age and preterm birth in Argentina, 2003–2007. Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juntarawijit, Y.; Juntarawijit, C. Cooking smoke exposure and respiratory symptoms among those responsible for household cooking: A study in Phitsanulok, Thailand. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apte, K.; Salvi, S. Household air pollution and its effects on health [version 1; peer review: 2 approved]. F1000Research 2016, 5, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonjour, S.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Wolf, J.; Bruce, N.G.; Mehta, S.; Prüss-Ustün, A.; Lahiff, M.; Rehfuess, E.A.; Mishra, V.; Smith, K.R. Solid fuel use for household cooking: Country and regional estimates for 1980–2010. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matinga, M.N.; Annegarn, H.J.; Clancy, J.S. Healthcare provider views on the health effects of biomass fuel collection and use in rural Eastern Cape, South Africa: An ethnographic study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 97, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Mishra, S.R.; Sharma, A.; Siweya, A.; Shrestha, N.; Adhikari, B. Geographic and socio-economic variation in markers of indoor air pollution in Nepal: Evidence from nationally-representative data. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, O.K.I.; Ezeh, O.K.; Agho, K.E.M.; Agho, K.E.; Dibley, M.J.; Dibley, M.J.O.; Hall, J.J.; Hall, J.J.O.; Page, A.N.; Page, A.N.I. The effect of solid fuel use on childhood mortality in Nigeria: Evidence from the 2013 cross-sectional household survey. Environ. Health 2014, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; CZ, B.N.; Mofizul Islam, M.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.M. Household air pollution from cooking and risk of adverse health and birth outcomes in Bangladesh: A nationwide population-based study. Environ. Health 2017, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddika, N.; Rantala, A.K.; Antikainen, H.; Balogun, H.; Amegah, A.K.; Ryti, N.R.I.; Kukkonen, J.; Sofiev, M.; Jaakkola, M.S.; Jaakkola, J.J.K. Short-term prenatal exposure to ambient air pollution and risk of preterm birth—A population-based cohort study in Finland. Environ. Res. 2020, 184, 109290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amegah, A.K.; Nayha, S.; Jaakkola, J.J. Do biomass fuel use and consumption of unsafe water mediate educational inequalities in stillbirth risk? An analysis of the 2007 Ghana Maternal Health Survey. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, E.; Adu-Bonsaffoh, K.; Vermeulen, R.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K.; Grobbee, D.E.; Browne, J.L.; Downward, G.S. Household fuel use and adverse pregnancy outcomes in a Ghanaian cohort study. Reprod Health 2020, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, N.; Perez-Padilla, R.; Albalak, R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: A major environmental and public health challenge. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000, 78, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, D.P.; Mishra, V.; Thompson, L.; Siddiqui, A.R.; Rehfuess, E.A.; Weber, M.; Bruce, N.G. Risk of low birth weight and stillbirth associated with indoor air pollution from solid fuel use in developing countries. Epidemiol. Rev. 2010, 32, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, A.; Khramtsova, G.; Brito, K.; Alexander, D.; Mueller, A.; Chinthala, S.; Adu, D.; Ibigbami, T.; Olamijulo, J.; Odetunde, A.; et al. Household air pollution and chronic hypoxia in the placenta of pregnant Nigerian women: A randomized controlled ethanol Cookstove intervention. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619–620, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanek, J. Hypoxic patterns of placental injury: A review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2013, 137, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoriadis, C.; Tympa, A.; Creatsa, M.; Bakas, P.; Liapis, A.; Kondi-Pafiti, A.; Creatsas, G. Hofbauer cells morphology and density in placentas from normal and pathological gestations. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obs. 2013, 35, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, S.; Prusac, I.K.; Roje, D.; Tadin, I. Trophoblast apoptosis in placentas from pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2011, 71, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heazell, A.; Moll, S.; Jones, C.; Baker, P.; Crocker, I. Formation of syncytial knots is increased by hyperoxia, hypoxia and reactive oxygen species. Placenta 2007, 28, S33–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meegdes, B.H.; Ingenhoes, R.; Peeters, L.L.; Exalto, N. Early pregnancy wastage: Relationship between chorionic vascularization and embryonic development. Fertil. Steril. 1988, 49, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.A.; Northcross, A.; Karrison, T.; Morhasson-Bello, O.; Wilson, N.; Atalabi, O.M.; Dutta, A.; Adu, D.; Ibigbami, T.; Olamijulo, J.; et al. Pregnancy outcomes and ethanol cook stove intervention: A randomized-controlled trial in Ibadan, Nigeria. Environ. Int. 2018, 111, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olopade, C.O.; Frank, E.; Bartlett, E.; Alexander, D.; Dutta, A.; Ibigbami, T.; Adu, D.; Olamijulo, J.; Arinola, G.; Karrison, T.; et al. Effect of a clean stove intervention on inflammatory biomarkers in pregnant women in Ibadan, Nigeria: A randomized controlled study. Environ. Int. 2017, 98, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program. Nigeria. (nd). Available online: www.dhsprogram.com/countries (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- National Population Commission (NPC) [NIGERIA] and ICF. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018; National Population Commission (NPC) [NIGERIA] and ICF: Abuja, Nigeria; Rockville, MD, USA, 2019.

- World Health Organization. New Global Estimates on Preterm Birth Published. Available online: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/global-estimates-preterm-birth/en/ (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- Coutinho, L.; Scazufca, M.; Menezes, P.R. Methods for estimating prevalence ratios in cross-sectional studies. Rev. Saude Publica 2008, 42, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, A.J.; Hirakata, V.N. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: An empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2003, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belitz, C.; Brezger, A.; Kneib, T.; Lang, S.; Umlauf, N. BayesX: Software for Bayesian Inference in Structured Additive Regression. Available online: http://www.bayesx.org (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Umlauf, N.; Adler, D.; Kneib, T.; Lang, S.; Zeileis, A. Structured additive regression models: An R interface to BayesX. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 63, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboye, O.A.; Gayawan, E.; Hanna, F. Spatial modelling of contribution of individual level risk factors for mortality from Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in the Arabian Peninsula. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatab, K.; Adegboye, O.; Mohammed, T.I. Social and demographic factors associated with morbidities in young children in Egypt: A Bayesian geo-additive semi-parametric multinomial model. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.; Smith, J.; Vehtari, A.; Plummer, M.; Stone, M.; Robert, C.P.; Titterington, D.; Nelder, J.; Atkinson, A.; Dawid, A. Discussion on the paper by Spiegelhalter, Best, Carlin and van der Linde. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2002, 64, 616–639. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelhalter, D.J.; Best, N.G.; Carlin, B.P.; Van Der Linde, A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 2002, 64, 583–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Akinyemi, J.O.; Morakinyo, O.M. Household environment and symptoms of childhood acute respiratory tract infections in Nigeria, 2003–2013: A decade of progress and stagnation. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory Data: Causes of Child Mortality; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Ko, T.-J.; Tsai, L.-Y.; Chu, L.-C.; Yeh, S.-J.; Leung, C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chou, H.-C.; Tsao, P.-N.; Chen, P.-C.; Hsieh, W.-S. Parental Smoking During Pregnancy and Its Association with Low Birth Weight, Small for Gestational Age, and Preterm Birth Offspring: A Birth Cohort Study. Pediatrics Neonatol. 2014, 55, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.K.; Bing, R.; Kiang, J.; Bashir, S.; Spath, N.; Stelzle, D.; Mortimer, K.; Bularga, A.; Doudesis, D.; Joshi, S.S. Adverse health effects associated with household air pollution: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and burden estimation study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1427–e1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel Olorunleke, A.; Auta, A.; Khanal, V.; Olasunkanmi David, B.; Akuoko, C.P.; Kazeem, A.; Samson, J.T.; Zhao, Y. Prevalence and factors associated with underutilization of antenatal care services in Nigeria: A comparative study of rural and urban residences based on the 2013 Nigeria demographic and health survey. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedokun, S.T.; Uthman, O.A.; Adekanmbi, V.T.; Wiysonge, C.S. Incomplete childhood immunization in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis of individual and contextual factors. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayawan, E.; Omolofe, O.T. Analyzing Spatial Distribution of Antenatal Care Utilization in West Africa Using a Geo-additive Zero-Inflated Count Model. Spat. Demogr. 2016, 4, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akwataghibe, N.N.; Ogunsola, E.A.; Broerse, J.E.; Popoola, O.A.; Agbo, A.I.; Dieleman, M.A. Exploring Factors Influencing Immunization Utilization in Nigeria—A Mixed Methods Study. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboye, O.A.; Kotze, D.; Adegboye, O.A. Multi-year trend analysis of childhood immunization uptake and coverage in Nigeria. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2014, 46, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Brezger, A.; Lang, S. Generalized structured additive regression based on Bayesian P-splines. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2006, 50, 967–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n (%) | PR (95% CI) b | p-Value b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Clean Cooking Fuel a | Unclean Cooking Fuel a | |||

| 4410 (10.69%) | 36,846 (89.31%) | ||||

| Demographic Variable (Mothers or Household) c | 41,821 | ||||

| Mother’s Age, mean ± SD | 35.9 ± 7.9 | 29.82 ± 9.04 | 29.1± 9.8 | NA | <0.0001 |

| Mother’s education | |||||

| No education | 14,398 (34.43) | 115 (0.28) | 14,173 (34.35) | ref | <0.0001 |

| Primary education | 6383 (15.26) | 252 (0.61) | 6062 (14.69) | 0.20 (0.16, 0.24) | |

| Secondary education | 16,698 (39.93) | 2189 (5.31) | 14,219 (34.47) | 0.05 (0.04, 0.06) | |

| Higher education | 4342 (10.38) | 1854 (4.49) | 2392 (5.80) | 0.01 (0.01, 0.01) | |

| Household wealth quintiles c | |||||

| Poorest | 7747 (18.52) | 5 (0.01) | 7682 (18.62) | ref | <0.0001 |

| Poorer | 8346 (19.96) | 11 (0.03) | 8243 (19.98) | 0.49 (0.15, 1.34) | |

| Middle | 8859 (21.18) | 91 (0.22) | 8934 (20.93) | 0.06 (0.02, 0.14) | |

| Richer | 8840 (21.13) | 656 (1.59) | 8020 (19.44) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.02) | |

| Richest | 8029 (19.20) | 3647 (8.84) | 4267 (10.34) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | |

| Mother’s exposure variable c | |||||

| Smoking Status | |||||

| Smoker | 96 (0.23) | 18 (0.04) | 75 (0.18) | 0.50 (0.30, 0.83) | 0.0111 |

| Non-smoker | 41,725 (99.77) | 4392 (10.65) | 36,771 (89.13) | ref | |

| Adverse birth outcome d | 127,545 | ||||

| Birth status | |||||

| Alive | 109,325 (85.701) | 7626 (6.03) | 100,669 (79.65) | ref | <0.0001 |

| Stillbirth | 18,220 (14.28) | 503 (0.40) | 17,598 (13.92) | 2.40 (2.21, 2.62) | |

| Birth weight e | |||||

| Normal weight (≥2500 g) | 7166 (92.73) | 1633 (21.60) | 5373 (71.05) | ref | 0.1250 |

| Low birth weight (<2500 g) | 562 (7.27) | 113 (1.49) | 442 (5.85) | 1.17 (0.96, 1.43) | |

| Duration of pregnancy f | |||||

| Term birth | 39,330 (99.00) | 2856 (7.28) | 35,972 (91.69) | ref | <0.0001 |

| Premature | 408 (1.00) | 59 (0.15) | 345 (0.88) | 0.47 (0.36, 0.62) | |

| Geographical variable c | |||||

| Region | |||||

| North-Central | 7772 (18.60) | 607 (1.47) | 7074 (17.15) | 7.21 (6.54, 7.97) | <0.0001 |

| North-East | 7639 (18.30) | 86 (0.21) | 7453 (18.07) | 53.65 (43.37, 67.29) | |

| North-West | 10,129 (24.20) | 376 (0.91) | 9703 (23.52) | 15.98 (14.24, 17.97) | |

| South-East | 5571 (13.30) | 390 (0.95) | 5004 (12.13) | ref | |

| South-South | 5080 (12.10) | 827 (2.00) | 4181 (10.13) | 3.13 (2.86, 3.43) | |

| South-West | 5630 (13.50) | 2124 (5.15) | 3431 (8.37) | 7.94 (7.08, 8.93) | |

| Characteristics | Birth Status: Stillbirth vs. Alive | Birth Weight: Low vs. Normal | Pregnancy Duration: Preterm vs. Term |

|---|---|---|---|

| p Mean (95% CrI) | p Mean (95% CrI) | p Mean (95% CrI) | |

| Cooking Fuel | |||

| Clean (ref) | |||

| Unclean | 0.14 (0.08, 0.20) | −0.09 (−0.31, 0.10) | −0.01 (−0.33, 0.31) |

| Education | |||

| No education (ref) | |||

| Primary | −0.07 (−0.10, −0.03) | 0.22 (−0.09, 0.49) | −0.04 (−0.33, 0.34) |

| Secondary | −0.23 (−0.26, −0.19) | 0.37 (0.08, 0.68) | 0.14 (−0.13, 0.42) |

| Higher | −0.39 (−0.45, −0.32) | 0.36 (0.06, 0.65) | 0.58 (0.24, 1.94) |

| Region | |||

| North-Central (ref) | |||

| North-East | 0.262 (0.01, 0.44) | 0.10 (−0.622, 0.88) | −0.01 (−0.64, 0.75) |

| North-West | 0.36 (−0.02, 0.60) | −0.52 (−1.21, 0.19) | −0.42 −0.99, 0.09) |

| South-East | −0.16 (−0.44, 0.07) | 0.23 (−0.57, 0.94) | −0.06 (−0.86, 0.70) |

| South-South | −0.15 (−0.35, 0.05) | 0.20 (−0.44, 0.77) | −0.11 (−1.01, 0.57) |

| South-West | −0.10 (−0.34, 0.15) | −0.02 (−0.73, 0.67) | 0.15 (−0.74, 0.77) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roberman, J.; Emeto, T.I.; Adegboye, O.A. Adverse Birth Outcomes Due to Exposure to Household Air Pollution from Unclean Cooking Fuel among Women of Reproductive Age in Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020634

Roberman J, Emeto TI, Adegboye OA. Adverse Birth Outcomes Due to Exposure to Household Air Pollution from Unclean Cooking Fuel among Women of Reproductive Age in Nigeria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020634

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoberman, Jamie, Theophilus I. Emeto, and Oyelola A. Adegboye. 2021. "Adverse Birth Outcomes Due to Exposure to Household Air Pollution from Unclean Cooking Fuel among Women of Reproductive Age in Nigeria" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 2: 634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020634

APA StyleRoberman, J., Emeto, T. I., & Adegboye, O. A. (2021). Adverse Birth Outcomes Due to Exposure to Household Air Pollution from Unclean Cooking Fuel among Women of Reproductive Age in Nigeria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020634