The Parent–Child Patient Unit (PCPU): Evidence-Based Patient Room Design and Parental Distress in Pediatric Cancer Centers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Psychological Impact of Childhood Cancer

1.2. The Relation between Childhood Cancer and Parental Distress

1.3. The Psychological Consequences of Hospitalization and the Birth of Rooming-In

1.4. The Architectural Consequences of Rooming-In and Its Relationship to the Psychosocial Distress of Parent and Child

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Behavioral Observation and Its Associated Architectural Determinants

2.2.2. Well-Being of the Child

2.2.3. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

2.2.4. Parental Perception of Uncertainty in Illness (PPUS)

2.2.5. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Respondents Characteristics

3.2. Patient Room Architecture

3.3. Parent–Child Interaction and Its Relationship to Architectural Determinants

3.4. Parental Stress

3.5. Association of Parental Disstress and Architectural Determinants

3.6. Association of Arental Stressor “Well-Being of the Child” and Architectural Determinants

4. Discussion

4.1. The Parent–Child Patient: A Negative Result of Patient Room Design

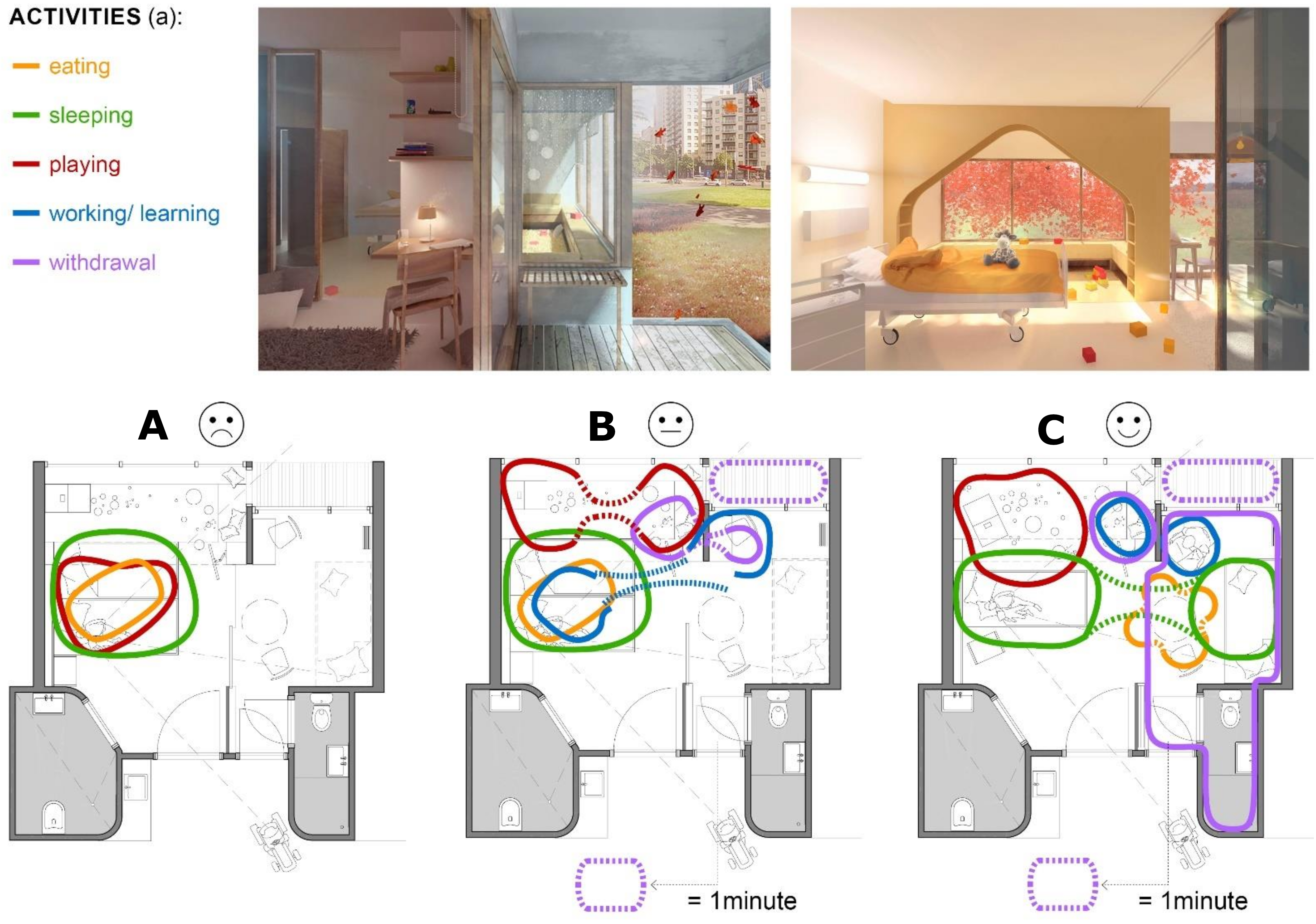

4.2. The Parent–Child Patient Unit (PCPU): A Consequent Architectural Approach Based on the Relationship of Patient Room Design and Parental Distress

- The patient room is divided into a child part and a parent part;

- Both parts can be separated acoustically and/or visually and gradually, for example, by a sliding door;

- Both parts have their own entrance and bathroom, as well as their own work or play and dining table;

- Parents have a view of their child from the bed when the door is open;

- The child part is clearly zoned into an entrance zone for medical and nursing activities and a private (play) zone where these activities do not occur;

- The parent part has direct access to an outdoor area, such as a terrace or balcony;

- The PCPU is embedded in functional services for parents within a perceived walking distance of one minute (1 min rule).

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allareddy, V.; Rampa, S.; Allareddy, V. Hospital charges and length of stay associated with septicemia among children hospitalized for leukemia treatment in the United States. World J. Pediatrics 2012, 8, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairuhu, A.M.; Andarsini, M.R.; Setyoningrum, R.A.; Cahyadi, A.; Larasati, M.C.S.; Ugrasena, I.D.G.; Permono, B.; Budiman, S. Hospital acquired pneumonia risk factors in children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia on chemotherapy. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R.A.; Stranges, E.; Elixhauser, A. Statistical Brief #132. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). In Pediatric Cancer Hospitalizations, 2009; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2016. Available online: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb132.jsp (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Shepley, M. The healthcare environment. In Meeting Children’s Psychosocial Needs Across the Health-Care Continuum; Rollins, J., Bolig, R., Mahan, C., Eds.; ProEd: Austin, TX, USA, 2005; pp. 313–349. [Google Scholar]

- Brain, D.J.; Maclay, I. Controlled Study of Mothers and Children in Hospital. Br. Med. J. 1968, 1, 278–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vollmer, T.C.; Koppen, G.; Vraetz, T.; Niemeyer, C. Entwicklungsräume. JuKiP-Ihr Fachmag. Für Gesundh. -Kinderkrankenpflege 2017, 6, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppen, G.; Vollmer, T.C. Architektur als zweiter Körper; Eine Entwurfslehre für den evidenzbasierten Gesundheitsbau; Gebr. Mann Verlag: Berlin, Germany. (in press)

- Vollmer, T.C. Architectural psychology in design education: Architekturpsychologie in der Entwurfslehre. In Healing Architecture: Entwerfen von Krankenhäusern und Bauten des Gesundheitswesens; Nickl-Weller, C., Ed.; BRAUN: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 210–213. [Google Scholar]

- Kopacz, E. Krebs bei Kindern: Parlament Schafft Bewusstsein. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/de/headlines/society/20200827STO85802/krebs-bei-kindern-parlament-schafft-bewusstsein (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Mokkink, L.B.; van der Lee, J.H.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Offringa, M.; Heymans, H.S.A. Defining chronic diseases and health conditions in childhood (0–18 years of age): National consensus in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Pediatrics 2008, 167, 1441–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, R.; Wallace, W.H.B.; Levitt, G. Long-term follow-up of children treated for cancer: Why is it necessary, by whom, where and how? Arch. Dis. Child. 2007, 92, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Dunn, M.J.; Rodriguez, E.M. Coping with chronic illness in childhood and adolescence. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 8, 455–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, M.I.R.; Radzinsky, T.C.; da Silva, N.S.; Chiari, B.M.; Consonni, D. Speech-Language and Hearing Complaints of Children and Adolescents with Brain Tumors. Pediatric Blood Cancer 2008, 50, 706–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, A.R.; Boss, R.D.; Donohue, P.K.; Shapiro, M.C.; Raisanen, J.C.; Henderson, C.M. Living in the Hospital: The Vulnerability of Children with Chronic Critical Illness. J. Clin. Ethics 2020, 31, 340–351. [Google Scholar]

- Cicogna, E.C. Crianças e adolescentes com câncer: Experiências com a quimioterapia. Dissertation, Escola de Enfermagem de Ribeirão Preto/USP, Ribeirão Preto, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Franck, L.S.; Wray, J.; Gay, C.; Dearmun, A.K.; Lee, K. Predictors of parent post-traumatic stress symptoms after child hospitalization on general pediatric wards: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wray, J.; Lee, K.; Dearmun, N.; Franck, L. Parental anxiety and stress during children’s hospitalisation: The StayClose study. J. Child Health Care 2011, 15, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commodari, E. Children staying in hospital: A research on psychological stress of caregivers. Ital. J. Pediatrics 2010, 36, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, L.S.; McQuillan, A.; Wray, J.; Grocott, M.P.W.; Goldman, A. Parent stress levels during children’s hospital recovery after congenital heart surgery. Pediatric Cardiol. 2010, 31, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabors, L.A.; Kichler, J.C.; Brassell, A.; Thakkar, S.; Bartz, J.; Pangallo, J.; van Wassenhove, B.; Lundy, H. Factors related to caregiver state anxiety and coping with a child’s chronic illness. Fam. Syst. Health 2013, 31, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, M.J.; Rodriguez, E.M.; Barnwell, A.S.; Grossenbacher, J.C.; Vannatta, K.; Gerhardt, C.A.; Compas, B.E. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in parents of children with cancer within six months of diagnosis. Health Psychol. 2012, 31, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoekstra-Weebers, J.E.H.M.; Wijnberg-Williams, B.J.; Jaspers, J.P.C.; Kamps, W.A.; van de Wiel, H.B.M. Coping and its effect on psychological distress of parents of pediatric cancer patients: A longitudinal prospective study. Psycho-Oncology 2012, 21, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, N.; Franck, L. Parent participation in the care of hospitalized children: A systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 622–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alisic, E.; Jongmans, M.J.; van Wesel, F.; Kleber, R.J. Building child trauma theory from longitudinal studies: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 31, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassam-Adams, N.; Fleisher, C.L.; Winston, F.K. Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of injured children. J. Trauma. Stress 2009, 22, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landolt, M.A.; Vollrath, M.; Ribi, K.; Gnehm, H.E.; Sennhauser, F.H. Incidence and associations of parental and child posttraumatic stress symptoms in pediatric patients. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2003, 44, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, N.R.; Ostrowski, S.; Christopher, N.C.; Delahanty, D.L. Parental posttraumatic stress symptoms as a moderator of child’s acute biological response and subsequent posttraumatic stress symptoms in pediatric injury patients. J. Pediatric Psychol. 2007, 32, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, J.E.; Jones, C.; Bienvenu, O.J. Family response to critical illness: Postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronner, M.B.; Kayser, A.-M.; Knoester, H.; Bos, A.P.; Last, B.F.; Grootenhuis, M.A. A pilot study on peritraumatic dissociation and coping styles as risk factors for posttraumatic stress, anxiety and depression in parents after their child’s unexpected admission to a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2009, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoppelbein, L.; Greening, L.; Wells, H. Parental coping and posttraumatic stress symptoms among pediatric cancer populations: Tests of competing models. Psycho-Oncology 2013, 22, 2815–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needle, J.S.; O’Riordan, M.; Smith, P.G. Parental anxiety and medical comprehension within 24 h of a child’s admission to the pediatric intensive care unit*. Pediatric Crit. Care Med. 2009, 10, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C.M.; Williams, E.P.; Shapiro, M.C.; Hahn, E.; Wright-Sexton, L.; Hutton, N.; Boss, R.D. “Stuck in the ICU”: Caring for Children With Chronic Critical Illness. Pediatric Crit. Care Med. 2017, 18, e561–e568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, F.A.; Alexander, E.; Davis, M.; Rennick, J.; Troini, R. Daily living with distress and enrichment: The moral experience of families with ventilator-assisted children at home. Pediatrics 2006, 117, e48–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.E.K.; Siegel, M.J.; Bauman, L.J. Double jeopardy: What social risk adds to biomedical risk in understanding child health and health care utilization. Acad. Pediatrics 2010, 10, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D. The effects of maternal deprivation: A review of findings and controversy in the context of research strategy. In Deprivation of Maternal Care: A Reassessment of Its Effects; Public Health Papers No. 14: Geneva, Switzerland, 1963; pp. 97–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.D.; Blehar, M.; Waters, E.; Wall, S. Patterns of Attachment. A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, D.B.; Prior, M.M. Preparation for surgery and adjustment to hospitalization. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 1994, 29, 655–669. [Google Scholar]

- Skipper, J.K.; Leonard, R.C. Children, Stress, and Hospitalization: A Field Experiment. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1968, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canright, P.; Campbell, M.J. Nursing care of the child and his family in the emergency department. Pediatric Nurs. 1977, 3, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, J.E.; Hayes, V.E. Hospitalization of a chronically ill child: A stressful time for parents. Issues Compr. Pediatric Nurs. 1983, 6, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, B.M. Parental coping with childhood hospitalization: A theoretical framework to guide research and clinical interventions. Matern. -Child Nurs. J. 1995, 23, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Broome, M.E. Working with the family of a critically ill child. Heart Lung: J. Crit. Care 1985, 14, 368–372. [Google Scholar]

- Dearden, R. The psychiatric aspects of the case study sample. In Hospitals, Children and Families: The Report of a Pilot Study; Stace, M., Ed.; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D. Social and psychological care before and during hospitalisation. Soc. Sci. Med. 1987, 25, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, M.R.; Dornbusch, S.M.; Herron, M.C.; Herting, J.R. The Influence of Family Regulation, Connection, and Psychological Autonomy on Six Measures of Adolescent Functioning. J. Adolesc. Res. 1997, 12, 34–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, M.E.; Lewis, C. The Role of Parent–Child Relationships in Child Development. In Social and Personality Development: An Advanced Textbook; Lamb, M.E., Bornstein, M.H., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 429–468. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M. Do the Parent–Child Relationship and Parenting Behaviors Differ Between Families With a Child With and Without Chronic Illness?: A Meta-Analysis. J. Pediatric Psychol. 2013, 38, 708–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.E.; Ladd, G.W. Connectedness and autonomy support in parent–child relationships: Links to children’s socioemotional orientation and peer relationships. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 36, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, M.S. Needs of parents of critically ill children. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. DCCN 1990, 9, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, H.R. The needs of parents with chronically sick children: A literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2001, 36, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I.; Conlon, J. Children’s and young people’s views of hospitalization: ‘It’s a scary place’. J. Child. Young People’s Nurs. 2007, 1, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.O.; Friedman, S.B.; Coupey, S.M. Adolescent preferences for rooming during hospitalization. J. Adolesc. Health 1998, 23, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I.T. Partnership in care: Parents’ views of participation in their hospitalized child’s care. J. Clin. Nurs. 1995, 4, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.B.; Hefley, G.C.; Anand, K.J.S. Parent bed spaces in the PICU: Effect on parental stress. Pediatric Nurs. 2007, 33, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Tandberg, B.S.; Flacking, R.; Markestad, T.; Grundt, H.; Moen, A. Parent psychological wellbeing in a single-family room versus an open bay neonatal intensive care unit. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, L.D. Adolescence, 9th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, L.L.; Wolfe-Christensen, C.; Pai, A.L.H.; Carpentier, M.Y.; Gillaspy, S.; Cheek, J.; Page, M. The relationship of parental overprotection, perceived child vulnerability, and parenting stress to uncertainty in youth with chronic illness. J. Pediatric Psychol. 2007, 32, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, S.K.; Carr, J.M. Vigilance: The experience of parents staying at the bedside of hospitalized children. J. Pediatric Nurs. 2004, 19, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franck, L.; Wray, J.; Gay, C.; Dearmun, A.K.; Alsberge, I.; Lee, K.A. Where do parents sleep best when children are hospitalized? A pilot comparison study. Behav. Sleep Med. 2014, 12, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franck, L.S.; Ferguson, D.; Fryda, S.; Rubin, N. The Child and Family Hospital Experience: Is It Influenced by Family Accommodation? Med. Care Res. Rev. 2015, 72, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriksen, K.; Isaacson, S.; Sadler, B.L.; Zimring, C.M. The Role of the Physical Environment in Crossing the Quality Chasm. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2007, 33, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepley, M.; Harris, D.; White, R.; Steinberg, F. Impact of Single Family NICU Rooms on Family Behavior. AIA Rep. Univ. Res. 2008, 3, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, A.; Kelly, A.; Konick, K. Transforming care in children’s hospitals through environmental design: Literature review. In Evidence for Innovation: Transforming Children’s Health through the Physical Environment, 1st ed.; National Association of Children’s Hospitals, Ed.; National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2008; pp. 18–95. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, B.H.; Jeppson, E.S.; Redburn, L. Caring for Children and Families. Guidelines for Hospitals, 1st ed.; Association for the Care of Children’s Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rollins, J.A. Tell Me About It: Drawing as a Communication Tool for Children With Cancer. J Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2005, 22, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fels, D.; Waalen, J.K.; Zhai, S.; Weiss, P. Telepresence under exceptional circumstances: Enriching the connection to school for sick children. In Proceedings of IFIP INTERACT01: Human-Computer Interaction 2001; IFIP Technical Committee No 13 on Human-Computer Interaction: Tokyo, Japan, 2001; pp. 617–624. [Google Scholar]

- Said, I.; Zaleha Salleh, S.; Abu Bakar, M.S.; Mohamad, I. Caregivers’ Evaluation On Hospitalized Children’s Preferences Concerning Garden And Ward. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2018, 4, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, A. The private adolescent: Privacy needs of adolescents in hospitals. J. Pediatric Nurs. 2002, 17, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, A. Activities in the adolescent ward environment. Contemp. Nurse 2003, 14, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmann, E. Family-centered care. In Core Curriculum for the Nursing Care of Children and Their Families, 1st ed.; Broome, M., Rollins, J.H., Eds.; Jannetti Publications Inc.: Pitman, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 373–392. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmann, E.; Rollins, J. The child with special healthcare needs. In Meeting Children’s Psychosocial Needs across the Health-Care Continuum; Rollins, J., Bolig, R., Mahan, C., Eds.; ProEd: Austin, TX, USA, 2005; pp. 175–219. [Google Scholar]

- Dunst, C.J.; Trivette, C.M.; Deal, A.G. Enabling and Empowering Families. Principles and Guidelines for Practice; Brookline Books: Newton, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hockenberry, M.J.; Wilson, D.; Barrera, P.; Wong, D.L. Wong’s Nursing Care of Infants and Children; Mosby/Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.; Green, J.G. The parent care pavilion. Child. Today 1977, 6, 5–8+36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Green, M.; Segar, W.E. Education: A new design for patient care and pediatric education in a children’s hospital: An interim report. Pediatrics 1961, 28, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koppen, G.; Vollmer, T.C. NKOC-Het Ontwikkelingsgericht Gebouw. Ontwerpuitgangspunten Resulterend uit Ontwerpend Onderzoek voor de Nieuwbouw van het Nederlands Kinder Oncologisch Centrum; SKION: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.T.; Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishel, M.H. Parents’ perception of uncertainty concerning their hospitalized child. Nurs. Res. 1983, 32, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.S.; Funk, S.G.; Kasper, M.A. The stress response of mothers and fathers of preterm infants. Res. Nurs. Health 1992, 15, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaney, J.M.; Gamwell, K.L.; Baraldi, A.N.; Ramsey, R.R.; Cushing, C.C.; Mullins, A.J.; Gillaspy, S.R.; Jarvis, J.N.; Mullins, L.L. Parent Perceptions of Illness Uncertainty and Child Depressive Symptoms in Juvenile Rheumatic Diseases: Examining Caregiver Demand and Parent Distress as Mediators. J. Pediatric Psychol. 2016, 41, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madeo, A.C.; O’Brien, K.E.; Bernhardt, B.A.; Biesecker, B.B. Factors associated with perceived uncertainty among parents of children with undiagnosed medical conditions. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2012, 158, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, F. Involving families in care within the intensive care environment: A descriptive survey. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 1995, 1, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, I.L.A.; Limeira, R.R.T.; Dias de Castro, R.; Ferreti Bonan, P.R.; Valença, A.M.G. Oral Mucositis in Pediatric Patients in Treatment for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornwell, P.L.; Murdoch, B.E.; Ward, E.C.; Kellie, S. Acoustic Investigation of Vocal Quality Following Treatment for Childhood Cerebellar Tumour. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2004, 56, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, N.S.; Gazendam, J.; Levan, L.; Pack, A.L.; Schwab, R.J. Abnormal sleep/wake cycles and the effect of environmental noise on sleep disruption in the intensive care unit. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 163, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, G.M.; Hajdukova, E.B.; Harding, C.; Flood, C.; McCourt, C.; Sellers, D.; Townsend, J.; Moss, D.; Tuffrey, C.; Donaldson, B.; et al. Psychosocial support for families of children with neurodisability who have or are considering a gastrostomy. The G-PATH mixed-methods study. Health Serv. Deliv. Res. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, L.; Kristensson-Hallström, I.; O´Callaghan, M. An examination of the needs of parents of hospitalized children: Comparing parents’ and staff’s perceptions. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2003, 17, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, L.S.; Caryl, L. Accommodating families during a child’s hospital stay: Implications for family experience and perceptions of outcomes. Fam. Syst. Health 2013, 31, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppen, G.; Vollmer, T.C. Weil Patientenorientierung kein Luxus, sondern Versorgungsauftrag ist! Qualitatives Raumkonzept, Patientenbereiche. In Neubauprojekt ´Unsere Kinder- und Jugendklinik Freiburg’; INITIATIVE: Freiburg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, E.M.; Dunn, M.J.; Zuckerman, T.; Vannatta, K.; Gerhardt, C.A.; Compas, B.E. Cancer-related sources of stress for children with cancer and their parents. J. Pediatric Psychol. 2012, 37, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, T.J.; Chen, E.; Munch, J.A.; Miller, G.E. Double-exposure to acute stress and chronic family stress is associated with immune changes in children with asthma. Psychosom. Med. 2009, 71, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juster, R.-P.; McEwen, B.S.; Lupien, S.J. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 35, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yantzi, N.; Rosenberg, M.W.; Burke, S.O.; Harrison, M.B. The impacts of distance to hospital on families with a child with a chronic condition. Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 1777–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, I. Environment and Social Behavior. Privacy, Personal Space, Territory, and Crowding; Monterey: Brooks/Cole, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Mulhall, A.; Kelly, D.; Pearce, S. A qualitative evaluation of an adolescent cancer unit. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2004, 13, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, V.L.; Greenberger, D.B. Destruction and perceived control. In Advances in Environmental Psychology, 2nd ed.; Baum, A., Singer, J.E., Singer, J.L., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1980; pp. 85–209. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.-H.; Robertson, M.M.; Chang, K.-I. The Role of Environmental Control on Environmental Satisfaction, Communication, and Psychological Stress. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 617–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, E.R.C.M.; Morales, E.; van Hoof, J.; Kort, H.S.M. Healing environment: A review of the impact of physical environmental factors on users. Build. Environ. 2012, 58, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, E.; Baylin, D. Choosing art as a complement to healing. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2007, 20, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Effects of interior design on wellness: Theory and recent scientific research. J. Healthc. Inter. Des. 1991, 3, 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, N.; Amarel, D. Effects of social support visibility on adjustment to stress: Experimental evidence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 458–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frampton, S.B.; Charmel, P.A.; Planetree (Eds.) Putting Patients First. Best Practices in Patient-Centered Care, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Planetree. Planetree pioneers: Angelica Thieriot. Available online: https://planetree.org/certification/about-planetree/ (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Malenbaum, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Williams, A.C.d.C.; Ulrich, R.; Somers, T.J. Pain in its environmental context: Implications for designing environments to enhance pain control. Pain 2008, 134, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, R.S. Effects of viewing art on health outcomes. In Putting Patients First: Best Practices in Patient-Centered Care, 2nd ed.; Frampton, S.B., Charmel, P.A., Planetree, Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 129–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Lunden, O.; Etinge, J.L. Effects of exposure to nature and abstract pictures on patients recovery from heart surgery. Paper presented at the 33rd Annual Meeting of the Society for Psychophysiological Research, Rottach-Egern, Germany, 1993. (Abstract published in Psychophysiology, 1993, 30 (supp. 1), 7.). [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Miles, M.A. Effects of environmental simulations and television on blood donor stress. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2003, 20, 38–47. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43030641 (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Ulrich, R.S.; Zimring, C.; Zhu, X.; DuBose, J.; Seo, H.-B.; Choi, Y.-S.; Quan, X.; Joseph, A. A review of the research literature on evidence-based healthcare design. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2008, 1, 61–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, M.G.; Jonides, J.; Kaplan, S. The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, J.K.; Hegadoren, K.; Coupland, N.J.; Rowe, B.H.; Neufeld, R.W.J.; Lanius, R.A. Cognitive distortions in an acutely traumatized sample: An investigation of predictive power and neural correlates. Psychol. Med. 2011, 41, 2149–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, S. Psychosocial Predictors of Distress in Parents of Children Undergoing Stem Cell or Bone Marrow Transplantation. J. Pediatric Psychol. 2005, 30, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, P.; Pradhan, P.V.; Shah, H. Psychopathology and coping in parents of chronically ill Children. Indian J. Pediatr. 2004, 71, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, C.; Herbst, J.L. The ethics of caring for hospital-dependent patients. BMC Med. Ethics 2017, 18, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekema, D.S. Parental refusals of medical treatment: The harm principle as threshold for state intervention. Theor. Med. Bioeth. 2004, 25, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, T. Hospital Hotel Crain’s Detroit Business. Detroit 1993, 9, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, S. Effects of furniture rearrangement on the atmosphere of wards in a maximum-security hospital. Hosp. Community Psychiatry 1985, 36, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Respondent | ||

| Mother | 12 | 55% |

| Father | 10 | 45% |

| Relationship status | ||

| In a relationship | 19 | 86% |

| Single parent | 2 | 9% |

| Divorced/widowed | 1 | 5% |

| Age of child | ||

| 0–2 | 9 | 40% |

| 3–5 | 3 | 15% |

| >5 | 10 | 45% |

| Medical diagnosis of child | ||

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | 2 | 9% |

| Leukemia [All] | 8 | 36% |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 4 | 18% |

| Glioblastoma | 1 | 5% |

| Brain tumor | 2 | 9% |

| Neuroblastoma | 2 | 9% |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | 5% |

| Osteosarcoma | 2 | 9% |

| Time interval to first diagnosis | ||

| 0–2 years | 16 | 73% |

| 3–5 years | 5 | 22% |

| >5 years | 1 | 5% |

| Distance from home | ||

| In the city | 12 | 55% |

| Suburbia up to 50 km from city | 9 | 40% |

| >50 km from city | 1 | 5% |

| Family first stay in hospital | ||

| No | 9 | 40% |

| Yes | 13 | 60% |

| Parental distress | Mean (SD) 1 | Range | Scores > 10 (%) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety (HADS) | 12.07 (4.11) | 5–20 | 52% |

| Depression (HADS) | 7.55 (4.13) | 0–16 | 33% |

| Uncertainty (PPUS) | 85.7 (13.4) | 60–133 | |

| Well-being of child (VAS) | |||

| MP 1 (day 1) | 2.8 3,* (0.2) | 1–3 | |

| MP 2 (day 4) | 2.2 3,* (0.6) | 1–3 | |

| MP 3 (day 7) | 1.5 3,* (0.5) | 1–3 |

| Architectural Determinants | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Disstress | Distance between Parent and Child | Used Space for Interaction | Used Possibilities for Withdrawal |

| Anxiety of parents (HADS) | −0.360 *** | −0.290 *** | −0.297 *** |

| Depression of parents (HADS) | −0.167 | 0.172 | 0.142 |

| Uncertainty of parents (PPUS) | 0.258 * | 0.199 * | 0.021 |

| Architectural Determinants | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Stressor | Distance between Parent and Child | Used Space for Interaction | Used Possibilities for Withdrawal |

| Well-being of child (VAS) | |||

| MP 1 (day 1) | 0.360 *** | 0.292 ** | 0.291 ** |

| MP 2 (day 4) | 0.177 * | 0.372 *** | 0.342 *** |

| MP 3 (day 7) | 0.333 *** | 0.352 *** | 0.151 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vollmer, T.C.; Koppen, G. The Parent–Child Patient Unit (PCPU): Evidence-Based Patient Room Design and Parental Distress in Pediatric Cancer Centers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199993

Vollmer TC, Koppen G. The Parent–Child Patient Unit (PCPU): Evidence-Based Patient Room Design and Parental Distress in Pediatric Cancer Centers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):9993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199993

Chicago/Turabian StyleVollmer, Tanja C., and Gemma Koppen. 2021. "The Parent–Child Patient Unit (PCPU): Evidence-Based Patient Room Design and Parental Distress in Pediatric Cancer Centers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 9993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199993

APA StyleVollmer, T. C., & Koppen, G. (2021). The Parent–Child Patient Unit (PCPU): Evidence-Based Patient Room Design and Parental Distress in Pediatric Cancer Centers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 9993. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18199993