Street Sexual Harassment: Experiences and Attitudes among Young Spanish People

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Conceptualisation of Street Sexual Harassment (SSH)

- (a)

- Harassment occurs in a public or semi-public space (street, public transport) and is contextualized by a face-to-face interaction between two unknown people, that is, people who share no stable, long-term or safe connection.

- (b)

- Even though stalking, as Lopez [2] points out, is also a type of SSH, this type of violence tends to occur within a brief or even fleeting interaction (which not only constitutes one of its main characteristics, but also differentiates it from other forms of violence, such as sexual harassment in the workplace or academic environment).

- (c)

- (d)

- The absence of an intimate or other relationship causes the behavior of the harasser to be perceived by the person harassed as an uncomfortable or even threatening transgression of her physical and psychological space.

- (e)

- The behavior is unidirectional (meaning that neither the desires nor situation of the victim are taken into account) with a singular objective (meaning it is not meant to be public nor indiscriminate).

- (f)

- (g)

- Although it may be considered a benign, harmless, or even normalized and socially tolerated act, it is an act of domination that impacts the sexual freedom and right to free movement of women, communicating the message that harassers have the right to occupy public spaces and to control, assault, or injure women. It therefore assumes the imposition of the desires of one (or a few) over another (or others) and has a sexual connotation that is degrading and that objectifies, humiliates, and threatens the woman (or women), provoking in her (them) discomfort or fear.

- (h)

- It may also include visual assault (leering), nonverbal assault (sexual and obscene gestures, sighs, whistles or noises), verbal assault (jeering, sexual comments, whether supposedly positive, offensive or insulting), and/or assault in the sense of physical invasion of privacy (exhibitionism, public masturbation, groping).

1.2. The Incidence of the Street Sexual Harassment (SSH)

1.3. The Types of Street Sexual Harassment (SSH)

1.4. The Perception of Street Sexual Harassment (SSH)

1.5. The Beliefs and Attitudes towards Street Sexual Harassment (SSH)

1.6. Study Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

- A sociodemographic data sheet with information related to gender (self-categorized by participants), age, economic level, current work status, and political opinion.

- A victimization questionnaire designed ad hoc, including eight questions with a 4-point scale answer relative to the frequency (1: No, never; 2: Yes, on one occasion; 3: Yes, on more than one occasion; and 4: Yes, regularly) with which the participants had been victims of (4 questions) or witness to (4 questions) 4 types of violence: robbery, SSH, sexual harassment, and intimate partner violence.

- A questionnaire on attitudes towards “piropos” [40] to measure attitudes towards a SSH situation: “piropos”. The following situation was presented: a young girl is walking alone down a street and receives the sexual attention of a group of young males, specifically a comment from one of them about ‘how hot she is’. The participants were asked to evaluate their perception of this situation, indicating their level of agreement according to a Likert scale (where 1 means ‘Not at all’ and 7 means ‘A lot’) regarding 7 items characterizing the situation (as fun, pleasant, flattering, male chauvinist, offensive, unpleasant, vulgar). For items 1, 2, and 3, the order of the scoring scale was inverted prior to the analysis so that higher scores reflected a negative attitude or rejection of the remark. According to the author, the scale offers good internal consistency (α = 0.91).

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Psychometric Properties of the Questionnaire on Attitudes towards “Piropos”

3.2. Frequencies of the Different Types of Victimization and Relationship with Gender

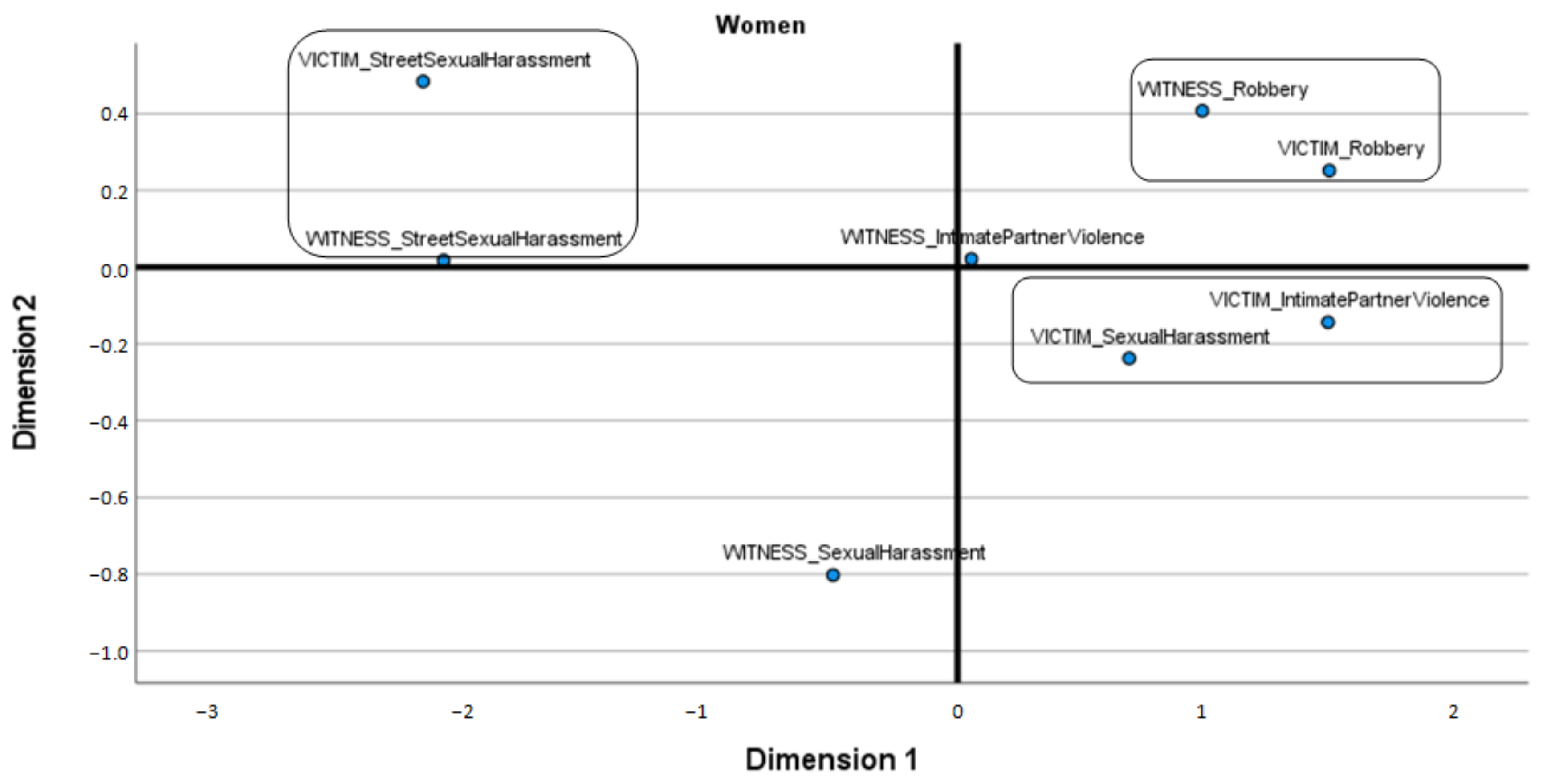

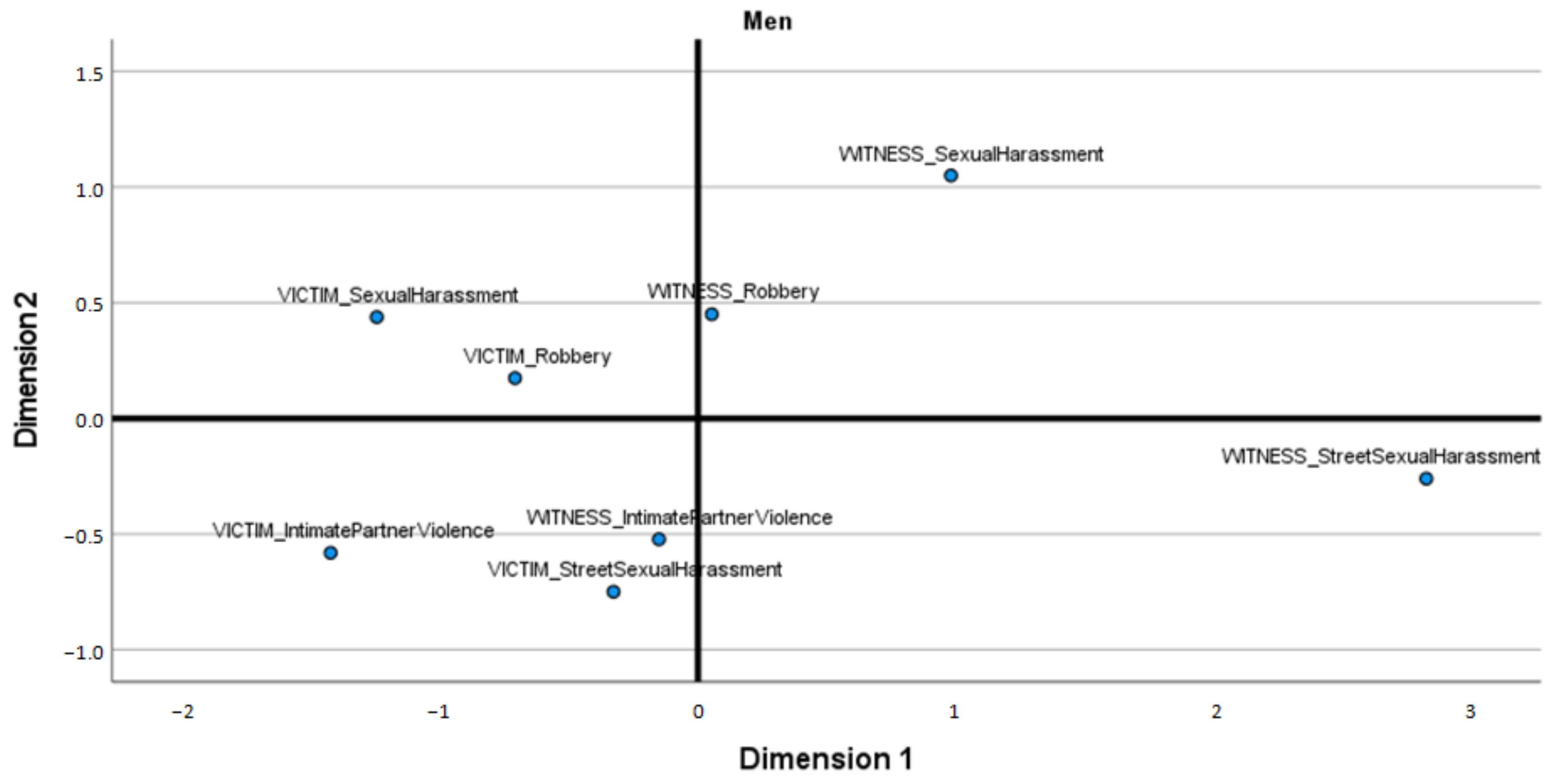

3.3. Relationships among Different Types of Victimization

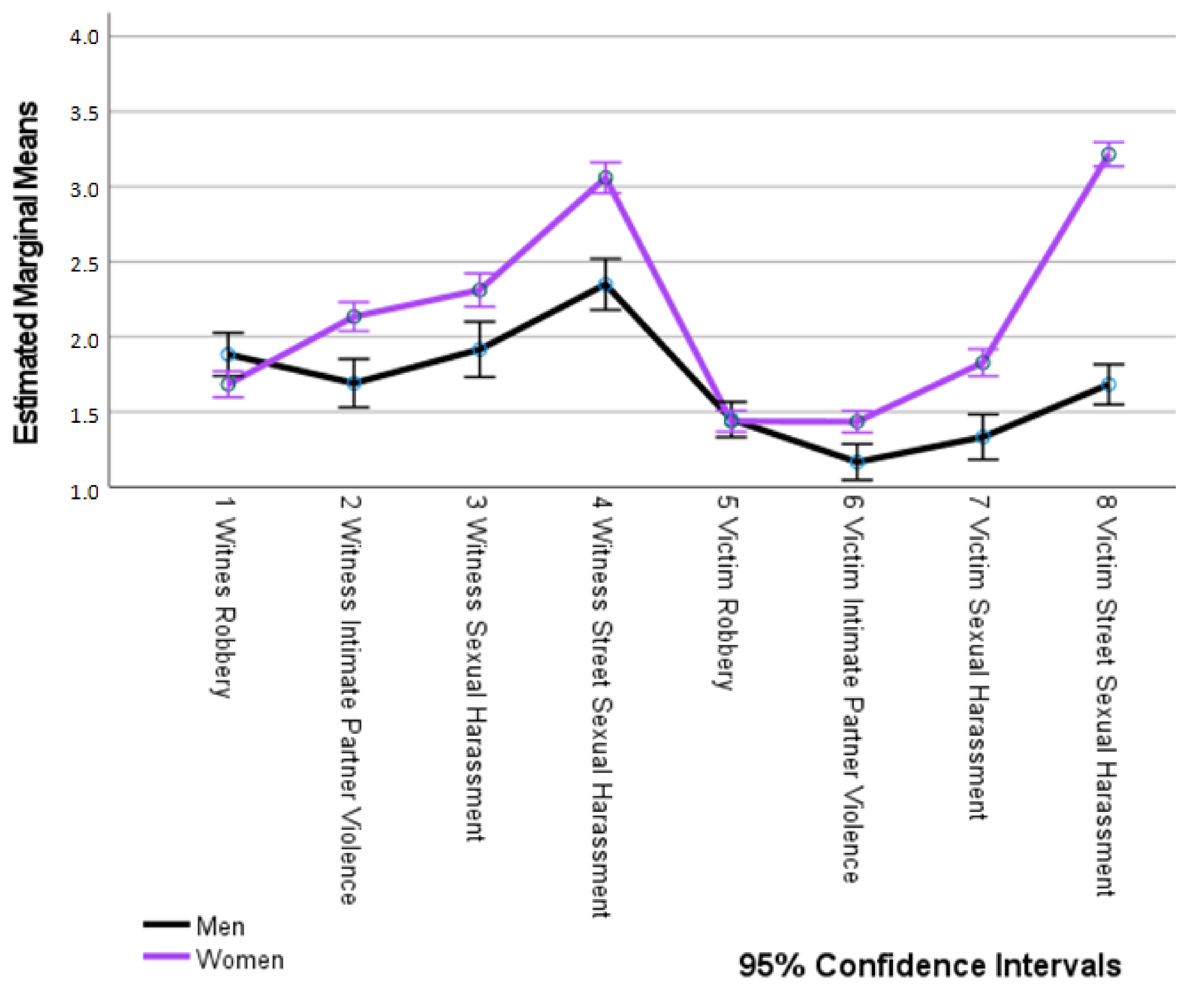

3.4. Victimization and Attitudes towards “Piropos” by Gender

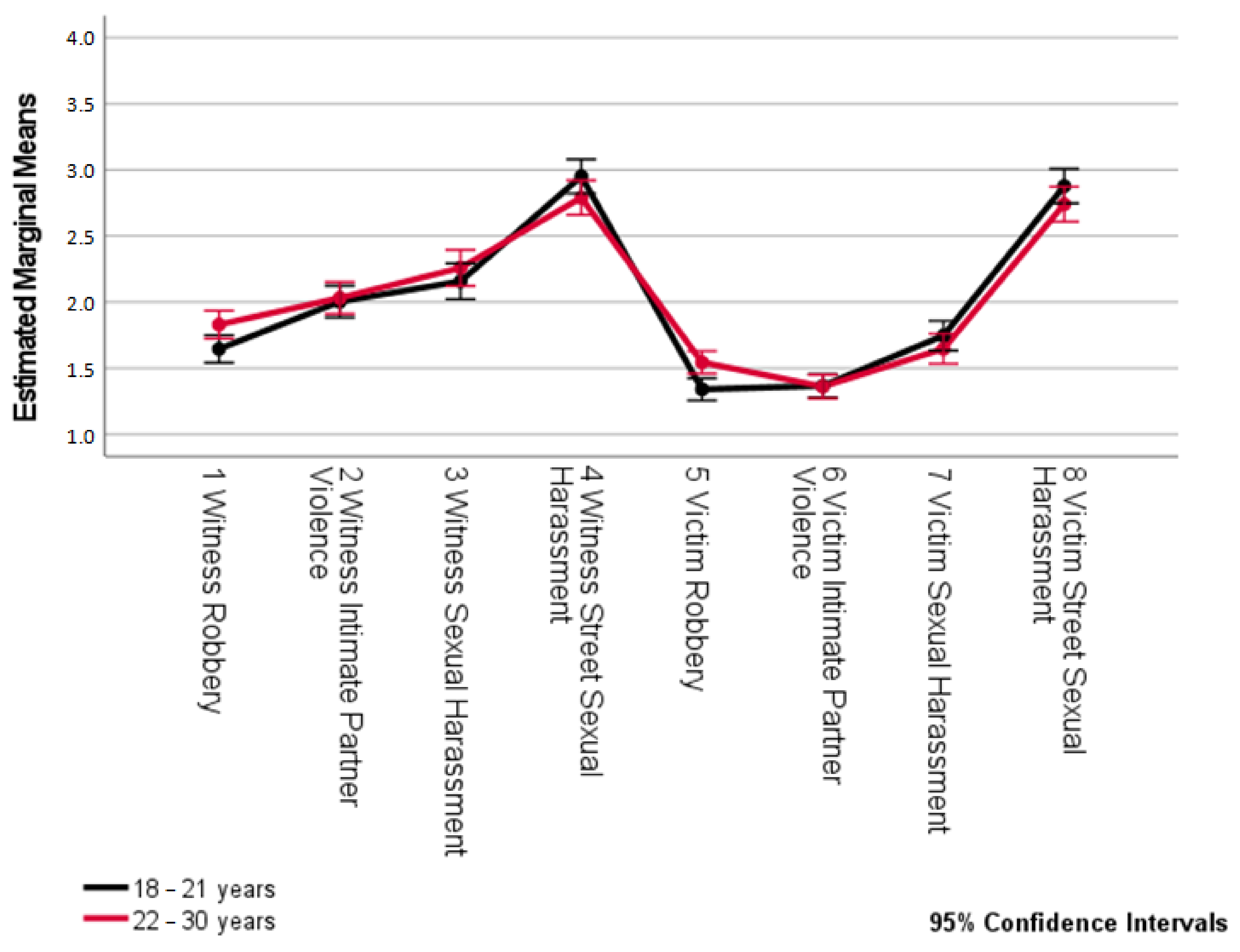

3.5. Victimization and Attitudes towards “Piropos” by Age

3.6. Relationship between Victimization and Attitude towards “Piropos” as a Function of Gender and Age

3.7. Attitudes towards “Piropos” and Other Sociodemographic Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN (United Nations). In-Depth Study on All Forms of Violence against Women. In Report of the Secretary-General (AG 61/122/Add.1); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N06/419/74/PDF/N0641974.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- López, M.C. Estado del arte sobre el acoso sexual callejero: Un estudio sobre aproximaciones teóricas y formas de resistencia frente a un tipo de violencia basada en género en América Latina desde el 2002 hasta el 2020. Cienc. Política 2020, 15, 195–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arancibia, J.; Billi, M.; Guerrero, M.J. ¡Tu ‘piropo’ me violenta! Hacia una definición de acoso sexual callejero como forma de violencia de género. Rev. Punto Género 2017, 7, 112–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rodríguez, Y.; Carrera, M.V.; Lameiras, M. Una radiografía del acoso sexual en España. In Informe España 2019; Blanco, A., Chueca, A., López-Ruiz, J.A., Mora, S., Eds.; Universidad Pontificia Comillas, Cátedra, J.M. Martín Patino: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 4–58. Available online: https://blogs.comillas.edu/informeespana/wp-content/uploads/sites/93/2019/10/IE2019Parte-2%C2%AA.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Rodríguez, Y.; Martínez, R.; Alonso, P. Análisis de las experiencias de mi primer acoso sexual callejero. In (Re)construíndo o coñecemento; López, A.J., Aguayo, E., Gómez, A., Eds.; Universidade da Coruña: A Coruña, Spain, 2019; pp. 421–429. Available online: https://ruc.udc.es/dspace/bitstream/handle/2183/24498/Reconstruindo_o_co%EF%BF%BDecemento_2019.pdf?sequence=5 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- UN-Women. Safe Cities Global Initiative. In Brief. 2014. Available online: http://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Farmer, O.; Smock, S. Experiences of women coping with catcalling experiences in New York City: A pilot study. J. Fem. Fam. Ther. 2017, 29, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, C.G. Street harassment and the informal ghettoization of women. Harv. Law Rev. 1993, 106, 517–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearl, H. The Facts behind the #Metoo Movement: A National Study on Sexual Harassment and Assault; Stop Street Harassment: Reston, VA, USA, 2018; Available online: http://www.stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Full-Report-2018-National-Study-on-Sexual-Harassment-and-Assault.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Logan, L.S. Street harassment: Current and promising avenues for researchers and activists. Sociol. Compass 2015, 9, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onetto, F.M.C. Hacia una reconceptualización del acoso callejero. Rev. Estud. Fem. 2019, 27, e57206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L.S. La utilidad del feminismo. Empoderamiento y visibilización de la violencia urbana en las mujeres jóvenes. Hábitat Soc. 2018, 11, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L.S.; Aguerri, J.C. Más allá del miedo urbano de la mujer joven. Prácticas de resignificación espacial y supervivencia a la violencia en la ciudad de Zaragoza. Encrucijadas. Rev. Crítica Cienc. Soc. 2018, 15, a1502. [Google Scholar]

- Escalona, M. Sororidad y resistencia digital ante el acoso sexual callejero. Hachetetepé. Rev. Científica Educ. Comun. 2019, 18, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, E.; Rivarola, M.P. La violencia invisible: Acoso sexual callejero en Lima Metropolitana y Callao. In Cuadernos de Investigación, 4; Instituto de Opinión Pública de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Perú: Lima, Perú, 2013; Available online: https://repositorio.pucp.edu.pe/index/handle/123456789/34946 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Vera-Gray, F. Men’s stranger intrusions: Rethinking street harassment. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum. Pergamon 2016, 58, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plan Internacional. Inseguras En Las Calles. Acoso En Grupo; Plan Internacional: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: http://bbpp.observatorioviolencia.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/nuevo_inseguras_v05_2.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Angelucci, L.; Romero, A.; Marcano, T.; Aquino, S.; Carrera, A.; De Jesús, R.; Tapia, V. Influencia del sexismo, el rol sexual y el sexo sobre percepción del acoso callejero. Rev. Investigium IRE Cienc. Soc. Y Hum. 2020, 11, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arancibia, J.; Billi, M.; Bustamante, C.; Guerrero, M.J.; Meniconi, L.; Molina, M.; Saavedra, P. Acoso Sexual Callejero: Contextos Y Dimensiones; OCAC (Observatorio Contra el Acaso Sexual Callejero): Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2015; Available online: https://www.ocac.cl/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Acoso-Sexual-Callejero-Contexto-y-dimensiones-2015.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Gaytan, P. El acoso sexual en lugares públicos: Un estudio desde la Grounded Theory. Cotidiano 2007, 22, 5–17. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/325/32514302.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- McCarty, M.K.; Iannone, N.E.; Kelly, J.R. Stranger danger: The role of perpetrator and context in moderating reactions to sexual harassment. Sex. Cult. 2014, 18, 739–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brox, A. Acoso sexista callejero: ¿Qué respuesta puede ofrecer el Derecho penal? Oñati Socio-Leg. Ser. 2019, 9, 983–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodemann, H.R. Derechos en conflicto: Una ley anti-piropo en España. Cuest. Género Igual. Difer. 2015, 10, 51–160. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, P. Men Harassing Men on the Street. Guest Blog post On Feministe, 10-15-12. Available online: https://stopstreetharassment.org/2012/10/maleharassment/ (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Meyer, D. An Intersectional Analysis of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) People’s Evaluations of Anti-Queer Violence. Gend. Soc. 2012, 26, 849–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmillan, R.; Nierobisz, A.; Welsh, S. Experiencing the streets: Harassment and perceptions of safety among women. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2000, 37, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearl, H. Unsafe and Harassed in Public Spaces: A National Street Harassment Report; Stop Street Harassment: Reston, VA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/2014-National-SSH-Street-Harassment-Report.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Clavaud, A.; Finchelstein, G.; Kraus, F. Les femmes face aux violences sexuelles et le harcèlement dans la rue. Enquête En Eur. Et Aux Etats-Unis. 2018. Available online: https://www.jean-jaures.org/wp-content/uploads/drupal_fjj/redac/commun/productions/2018/enquete_harcelement_0.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Gutiérrez, N.; Lovo, E. Acoso Callejero en la Ciudad: Aproximación Descriptiva Sobre el Acoso Callejero en el Area Urbana de Managua; Observatorio Contra el Acoso Callejero Nicaragua: Managua, Nicaragua, 2015; Available online: https://www.stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Informe-Acoso-Callejero-en-la-ciudad_OCAC-Nicaragua.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Campos, P.A.; Falb, K.L.; Hernández, S.; Díaz-Olavarrieta, C.; Gupta, J. Acoso en la calle y su asociación con percepciones de cohesión social entre mujeres en la Ciudad de México. Salud Pública México 2017, 59, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, M.E.; García, S. Adolescent street harassment in Querétaro, Mexico. J. Women Soc. Work 2015, 30, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Women. Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces for Women and Girls Global Flagship Initiative: International Compendium of Practices; UN-Women: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2019/safe-cities-and-safe-public-spaces-compendium-of-practices-en.pdf?la=en&vs=2609 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- OCAC (Observatorio Contra el Acoso Callejero). Primera Encuesta De Acoso Callejero En Chile. Informe De Resultados; OCAC: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2014; Available online: https://www.ocac.cl/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Informe-Encuesta-de-Acoso-Callejero-2014-OCAC-Chile.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Llerena, R. Percepción y actitudes frente al acoso sexual callejero en estudiantes mujeres de una universidad privada de medicina. Horiz. Med. 2016, 16, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Women. Safe Cities Global Initiative. 2015. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/~/media/44F28561B84548FE82E24E38E825ABEA.ashx (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Rodríguez, Y.; Martínez, R.; Alonso, P.; Carrera, M.V. Análisis de la campaña #PrimAcoso: Un continuo de violencias sexuales. Convergencia 2021, 28, e14300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Garofano, A.; Rodríguez-Bailón, R.; Moya, M.; López-Megías, J. Stranger harassment (“piropo”) and women’s self-objectification: The role of anger, happiness, and empowerment. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 2306–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, S.; Caja, N.; Rueda, P. Percepción femenina del acoso callejero. Int. e-J. Crim. Sci. 2019, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- González, H.; Cavazzoni, A.Z.; Gómez, L. Construcción y validación de un cuestionario que mide el acoso sexual callejero percibido por mujeres. Sci. Rev. Multidiscip. 2019, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Moya-Garofano, A. Cosificación De Las Mujeres: Análisis De Las Consecuencias Psicosociales De Los Piropos. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2016. Available online: https://digibug.ugr.es/handle/10481/43577 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Moya-Garofano, A.; Moya, M.; López-Megías, J.; Rodríguez-Bailón, R. Social perception of women according to their reactions to a stranger harassment situation (piropo). Sex Roles 2020, 83, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledezma, A.M. “Mijita Rica”: The female body as a subject in the public space. Generos. Multidiscip. J. Gend. Stud. 2017, 6, 1290–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, J.; Ochoa, M. Violencia de género y ciudad: Cartografías feministas del temor y el miedo. Soc. Econ. 2017, 32, 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Alcalde, M.C. Gender, autonomy, and return migration: Negotiating street harassment in Lima, Peru. Glob. Netw. 2018, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretta, R.F.; Szymanski, D.M. Stranger harassment and PTSD symptoms: Roles of self-blame, shame, fear, feminine norms, and feminism. Sex Roles 2020, 82, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelGreco, M.; Christensen, J. Effects of street harassment on anxiety, depression, and sleep quality of college women. Sex Roles 2020, 82, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fileborn, B. Bystander intervention from the victims’ perspective: Experiences, impacts and justice needs of street harassment victims. J. Gend.-Based Violence 2017, 1, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownmiller, S. Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, M.; Pease, B. Factors influencing attitudes to violence against women. Trauma Violence Abus. 2009, 10, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L. Factors influencing attitude toward intimate partner violence. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2016, 29, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairchild, K.; Nguyen, H. Perceptions of victims of street harassment: Effects of nationality and hair color in Vietnam. Sex. Cult. 2020, 24, 1957–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, A.; Herrera, M.C. Efectos del contexto y la ideología en la percepción del acoso. In Psicología Jurídica. Conocimiento Y Práctica; Bringas, C., Novo, M., Eds.; Sociedad Española de Psicología Jurídica y Forense: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2017; pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Escartín, J.; Salin, D.; Rodríguez-Carballeira, A. El acoso laboral o "mobbing": Similitudes y diferencias de género en su severidad percibida. Rev. Psicol. Soc. 2013, 28, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, A.; Pina, A.; Herrera, M.C.; Expósito, F. ¿Mito o realidad? Influencia de la ideología en la percepción social del acoso sexual. Anu. Psicol. Jurídica 2014, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, S.A.; González, J.A. La generación Z y los retos del docente. In Los retos de la Docencia ante las Nuevas Características de los Estudiantes Universitarios; ECORFAN Proceedings; Velasco, I., Páez, M., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Mayarit: Mayarit, México, 2016; pp. 116–133. Available online: https://www.ecorfan.org/proceedings/CDU_XI/PROCEEDING%20TOMO%2011.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Howe, N.; Strauss, W. Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, V.A.; Bosch, E. The perception of sexual harassment at university. Rev. Psicol. Soc. 2014, 29, 462–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Perez, V.A.; Bosch-Fiol, E.; Ferreiro-Basurto, V.; Delgado-Alvarez, C.; Sánchez-Prada, A. Comparing implicit and explicit attitudes toward intimate partner violence against women. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, E.; Lila, M. Attitudes towards Violence against Women in the EU; European Commission Directorate-General for Justice: Luxembourg, 2015; Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/a8bad59d-933e-11e5-983e-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Sánchez-Prada, A.; Delgado-Alvarez, C.; Bosch-Fiol, E.; Ferreiro-Basurto, V.; Ferrer-Perez, V.A. Psychosocial implications of supportive attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women throughout the lifecycle. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez, I.; Guijarro, C. Actitudes y experiencia sexual en mujeres jóvenes. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval.–E Avaliação Psicol. 2000, 1, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

| Country and Year of the Study | Source | Method | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada, 1993 | MacMillan et al. [26] | General female population survey | More than 80% of women surveyed had experienced SSH. |

| USA, 2014 | Kearl [9] Stop Street Harassment [27] | Sociological survey | SSH is a significant problem in the country. It has been experienced by 65% of women, especially in the forms of verbal (57%) and physical (41%) harassment. |

| Foundation Jean Jaurés multi-country study, 2018—USA | Clavaud et al. [28] | Survey on sexual violence and street harassment | Fifty-seven percent of women (especially young women) have experienced at least one SSH situation in their lifetime: 70% whistling; 50% sexist comments, teasing or insults; 46% rude gestures with sexual connotations; 41% touching in a sexual way without their consent. |

| Nicaragua, 2014 | Gutierrez & Lovo [29] | Sociological survey | More than 95% of women interviewed had experienced at least once situation of SSH, especially through gestures or verbal language and on the street, in markets, or on public transport. Nearly 41% had experienced a strong SSH experience, (experiences that, because of their severity and context, were remembered as causing more fear, anger, or frustration, and/or as leading to changes in their routines or behaviors). |

| Mexico, Mexico City, 2013 | Campos et al. [30] | Survey | A total of 62.8% of women who sought services at Mexico City Government Health Secretariat clinics reported having experienced some type of SSH in the previous month. |

| México, Queretaro, 2014 | Meza & García [31] | Survey of adolescents aged 13–15 | Almost half of the adolescents had experienced SSH situations, almost 70% of girls had experienced SSH. |

| Uruguay, 2013 | UN-Women [32] | Sociological survey about VAW | More than 50% of women aged 15–29 had experienced some form of sexual harassment in public spaces in the previous year. |

| Ecuador, Quito, 2012 | UN-Women [32] | Survey on the Quito Safe City Programme | More than 65% of women had experienced some form of sexual harassment in the city, often on public transport. |

| Chile, 2014 | OCAC [33] | Sociological survey | A total of 99.4% of women experienced SSH at some point, almost 40% daily, and 77% at least once a week. |

| Perú, 2012 | Vallejo & Rivarola [15] | National Survey on Family and Gender Roles. Public Opinion Institute of the PUCP | SSH practices mainly affected young women and female students. |

| Perú, Lima, 2016 | Llerena [34] | Questionnaire administered to female university students | Ninety-one percent had experienced at least one SSH situation in the previous year. |

| Multi-country study, 2018 | Plan Internacional [17] | Social survey tool on maps in Madrid, Delhi, Kampala, Lima, and Sidney | There was a significant volume of SSH complaints perpetrated by groups on girls and young women in the five cities analyzed, especially on the street and on public transport. |

| Fondation Jean Jaurés multi-country study, 2018—Europe | Clavaud et al. [28] | Survey on sexual violence and street harassment in France, Germany, Spain, Italy, and United Kingdom | Fifty-six percent of women surveyed (especially young women) had experienced at least one SSH situation in their lifetime: 65% whistling; 36% sexist comments, teasing or insults |

| United Kingdom, London, 2012 | UN-Women [35] | No information | Forty-three percent of young women had experienced SSH in the previous year. |

| France, 2013 | UN-Women [35] | No information | Twenty percent of women had experienced SSH in the previous year. |

| Spain, 2016 | Rodríguez, et al. [5] Rodríguez, et al. [36] | Analysis of tweets on the topic | Around 75% of the harassment situations described had occurred in public places, mainly to young women and in the street. |

| Spain, 2016 | cited in Moya-Garofano et al. [37] | Questionnaire administered to female university students | A total of 25.9% of participants had experienced SSH through rude catcalling 2–4 times a month, 17.8% at least once a month, and only 5.5% had never experienced catcalling. |

| Fondation Jean Jaurés multi-country study, 2018—Spain | Clavaud et al. [28] | Survey on sexual violence and street harassment | Fifty-five percent of women (especially young women) had experienced at least one SSH situation in their lifetime: 86% whistling; 76% insistent looks; 50% rude gestures with sexual connotations; 44% insistent approaches without consent, and 40% following, or sexist comments, teasing or insults. |

| Spain, 2018 | Varela, Caja & Rueda [38] | Survey of women aged 14 to 66 years old | Ninety-nine percent had experienced SSH: 32% occasionally, 31% monthly, 25% weekly, 12% daily. |

| Variable | Classification | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Educational level | Primary | 3 (0.6%) |

| Secondary | 310 (57.6%) | |

| Professional training | 64 (11.9%) | |

| University | 161 (29.9%) | |

| Labor situation | Unemployed | 38 (16.5%) |

| Employed | 139 (25.8%) | |

| Students | 360 (66.9%) | |

| No reply | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Economical level | Low | 89 (16.5%) |

| Medium-low | 155 (28.8%) | |

| Medium-medium | 242 (45.0%) | |

| Medium-high | 50 (9.3%) | |

| High | 2 (0.4%) | |

| Political opinion | Left | 371 (69.0%) |

| Centre | 106 (19.7%) | |

| Right | 35 (6.5%) | |

| Others | 1 (0.2%) | |

| No reply | 23 (4.3%) | |

| Current partner | Yes | 79 (14.7%) |

| No | 452 (84.0%) | |

| No reply | 7 (1.3%) |

| Items | Unrotated Matrix | |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

| 1. It is fun * | 0.696 | 0.499 |

| 2. It is nice * | 0.599 | 0.515 |

| 3. It is flattering * | 0.699 | 0.318 |

| 4. It is sexist (macho) | 0.738 | −0.211 |

| 5. It is offensive | 0.800 | −0.298 |

| 6. It is unpleasant | 0.846 | −0.313 |

| 7. It is disgusting | 0.848 | −0.259 |

| Type | Frequency | Gender | Witness | Victim | χ2 (3 df) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robbery n = 453 | Never | Men | 50 (41.7%) | 75 (62.5%) | Witness χ2 = 7.37 p = 0.061 Victim χ2 = 1.56 p = 0.459 |

| Women | 171 (51.4%) | 219 (65.8%) | |||

| Once | Men | 35 (29.2%) | 36 (30.0%) | ||

| Women | 96 (28.8%) | 82 (24.6%) | |||

| More than once | Men | 34 (28.3%) | 9 (7.5%) | ||

| Women | 66 (19.8%) | 32 (9.6%) | |||

| Usually | Men | 1 (0.8%) | - | ||

| Women | - | - | |||

| Intimate Partner Violence n = 537 | Never | Men | 83 (58.9%) | 124 (87.9%) | Witness χ2 = 38.75 p < 0.001 Victim χ2 = 17.30 p = 0.001 |

| Women | 122 (30.8%) | 279 (70.3%) | |||

| Once | Men | 20 (14.2%) | 11 (7.8%) | ||

| Women | 112 (28.2%) | 67 (16.9%) | |||

| More than once | Men | 30 (27.0%) | 6 (4.3%) | ||

| Women | 145 (36.6%) | 48 (12.1%) | |||

| Usually | Men | - | - | ||

| Women | 17 (4.3%) | 2 (0.5%) | |||

| Sexual Harassment n = 537 | Never | Men | 64 (45.4%) | 110 (78.0%) | Witness χ2 = 22.62 p < 0.001 Victim χ2 = 38.10 p < 0.001 |

| Women | 124 (31.2%) | 191 (48.2%) | |||

| Once | Men | 24 (17.0%) | 15 (10.6%) | ||

| Women | 37 (9.3%) | 92 (23.2%) | |||

| More than once | Men | 49 (34.8%) | 16 (11.3%) | ||

| Women | 196 (49.5%) | 106 (26.8%) | |||

| Usually | Men | 4 (2.8%) | - | ||

| Women | 39 (9.8%) | 7 (1.8%) | |||

| Street Sexual Harassment n = 537 | Never | Men | 42 (29.8%) | 81 (57.4%) | Witness χ2 = 57.39 p < 0.001 Victim χ2 = 230.5 p < 0.001 |

| Women | 40 (10.1%) | 21 (5.3%) | |||

| Once | Men | 18 (12.8%) | 25 (17.7%) | ||

| Women | 30 (7.6%) | 23 (5.8%) | |||

| More than once | Men | 70 (49.6%) | 34 (24.1%) | ||

| Women | 187 (47.1%) | 235 (59.3%) | |||

| Usually | Men | 11 (7.8%) | 1 (0.7%) | ||

| Women | 139 (35.0%) | 117 (29.5%) |

| Variable | Lévène (p) | Gender | n | Mean (SD) | df | t Student | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Witness to Robbery | 0.399 | Men | 120 | 1.88 (0.852) | 471 | 2.326 | 0.020 |

| Women | 333 | 1.68 (0.784) | |||||

| Witness to Intimate Partner Violence | 0.716 | Men | 141 | 1.68 (0.873) | 535 | −5.246 | <0.001 |

| Women | 396 | 2.14 (0.910) | |||||

| Witness to Sexual Harassment | 0.088 | Men | 141 | 1.95 (0.959) | 535 | −4.316 | <0.001 |

| Women | 396 | 2.38 (1.030) | |||||

| Witness to Street Sexual Harassment | 0.000 | Men | 141 | 2.35 (0.994) | 228.779 | −7.536 | <0.001 |

| Women | 396 | 3.07 (0.910) | |||||

| Victim of Robbery | 0.673 | Men | 120 | 1.45 (0.633) | 451 | 0.169 | 0.868 |

| Women | 333 | 1.44 (0.663) | |||||

| Victim of Intimate Partner Violence | 0.000 | Men | 141 | 1.16 (0.472) | 376.230 | −4.902 | <0.001 |

| Women | 396 | 1.43 (0.720) | |||||

| Victim of Sexual Harassment | 0.000 | Men | 141 | 1.33 (0.673) | 323.972 | −6.756 | <0.001 |

| Women | 396 | 1.82 (0.889) | |||||

| Victim of Street Sexual Harassment | 0.000 | Men | 141 | 1.68 (0.865) | 217.650 | −17.734 | <0.001 |

| Women | 396 | 3.13 (0.741) | |||||

| Attitudes toward “piropos” | 0.000 | Men | 139 | 42.72 (7.73) | 207.499 | −4.243 | <0.001 |

| Women | 396 | 45.82 (6.73) |

| Variable | Lévène (p) | Age | n | Mean (SD) | df | t Student | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Witness to Robbery | 0.581 | 18–21 | 229 | 1.65 (0.785) | 451 | −2.443 | 0.015 |

| 22–30 | 224 | 1.83 (0.819) | |||||

| Witness to Intimate Partner Violence | 0.478 | 18–21 | 306 | 2.00 (0.934) | 535 | −0.646 | 0.519 |

| 22–30 | 231 | 2.05 (0.907) | |||||

| Witness to Sexual Harassment | 0.874 | 18–21 | 306 | 2.25 (1.031) | 535 | −0.295 | 0.768 |

| 22–30 | 231 | 2.28 (0.1027) | |||||

| Witness to Street Sexual Harassment | 0.355 | 18–21 | 306 | 2.95 (0.976) | 535 | 1.805 | 0.072 |

| 22–30 | 231 | 2.80 (0.990) | |||||

| Victim of Robbery | 0.000 | 18–21 | 229 | 1.34 (0.590) | 434.971 | −3.348 | 0.001 |

| 22–30 | 224 | 1.54 (0.701) | |||||

| Victim of Intimate Partner Violence | 0.682 | 18–21 | 306 | 1.35 (0.677) | 535 | −0.311 | 0.756 |

| 22–30 | 231 | 1.37 (0.672) | |||||

| Victim of Sexual Harassment | 0.693 | 18–21 | 306 | 1.71 (0.860) | 535 | 0.405 | 0.685 |

| 22–30 | 231 | 1.68 (0.871) | |||||

| Victim of Street Sexual Harassment | 0.008 | 18–21 | 306 | 2.77 (1.063) | 524.602 | 0.465 | 0.636 |

| 22–30 | 231 | 2.73 (0.923) | |||||

| Attitudes toward “piropos” | 0.163 | 18–21 | 305 | 45.35 (6.149) | 533 | 1.329 | 0.185 |

| 22–30 | 230 | 44.56 (7.730) |

| Variable | Classification | n | Mean | SD | F | p | G.-H * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational level | Secondary | 307 | 45.03 | 6.97 | F(2.529) = 0.850 | 0.428 | ---- |

| Professional training | 64 | 44.08 | 8.01 | ||||

| University | 161 | 45.40 | 6.20 | ||||

| Labor situation | Unemployed | 38 | 42.47 | 9.88 | F(2.529) = 4.325 | 0.014 | N.S. ** |

| Employed | 138 | 44.33 | 7.73 | ||||

| Students | 358 | 45.53 | 6.04 | ||||

| Economical level | Low/Medium-low | 243 | 44.94 | 7.20 | F(2.532) = 3.402 | 0.034 | N.S. ** |

| Medium-medium | 241 | 45.55 | 5.84 | ||||

| Medium-high/High | 51 | 42.80 | 9.20 | ||||

| Political opinion | Left | 369 | 46.49 | 5.48 | F(2.506) = 24.774 | <0.001 | Left-Centre Left-Right *** |

| Centre | 105 | 42.82 | 8.19 | ||||

| Right | 35 | 40.54 | 7.69 | ||||

| Current partner | Yes | 79 | 45.44 | 5.701 | F(1.529) = 0.346 | 0.557 | |

| No | 452 | 44.95 | 7.076 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferrer-Perez, V.A.; Delgado-Alvarez, C.; Sánchez-Prada, A.; Bosch-Fiol, E.; Ferreiro-Basurto, V. Street Sexual Harassment: Experiences and Attitudes among Young Spanish People. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10375. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910375

Ferrer-Perez VA, Delgado-Alvarez C, Sánchez-Prada A, Bosch-Fiol E, Ferreiro-Basurto V. Street Sexual Harassment: Experiences and Attitudes among Young Spanish People. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10375. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910375

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerrer-Perez, Victoria A., Carmen Delgado-Alvarez, Andrés Sánchez-Prada, Esperanza Bosch-Fiol, and Virginia Ferreiro-Basurto. 2021. "Street Sexual Harassment: Experiences and Attitudes among Young Spanish People" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10375. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910375

APA StyleFerrer-Perez, V. A., Delgado-Alvarez, C., Sánchez-Prada, A., Bosch-Fiol, E., & Ferreiro-Basurto, V. (2021). Street Sexual Harassment: Experiences and Attitudes among Young Spanish People. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10375. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910375