Evaluations of Interventions with Child Domestic Workers: A Rapid Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

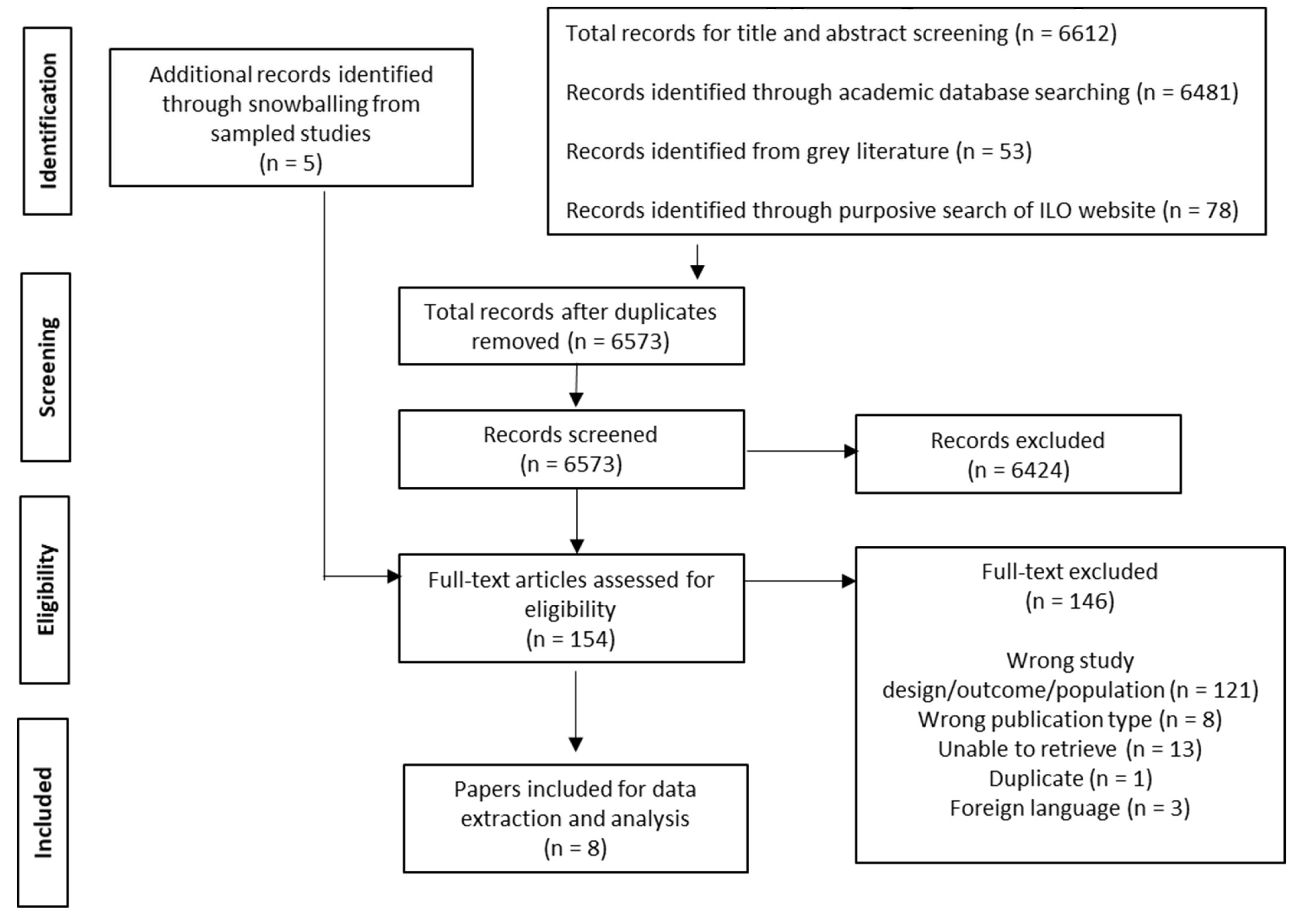

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Appraisal

3. Results

3.1. Health-Related Outcomes

3.2. Education-Related Outcomes

3.3. Economic Outcomes

3.4. Employer-Related Interventions

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNICEF. Child Domestic Work. In Innocenti Digest; UNICEF International Child Development Centre: Florence, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Ending Child Labour in Domestic Work and Protecting Young Workers from Abusive Working Conditions; ILO–IPEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/ipec/Informationresources/WCMS_207656/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Anderson, B. Doing the Dirty Work: The Global Politics of Domestic Labour; Zed Books: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, P.C. Maid or madam? Filipina migrant workers and the continuity of domestic labor. Gend. Soc. 2003, 17, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radcliffe, S.A. Between hearth and labor market: The recruitment of peasant women in the Andes. Int. Mig. Rev. 1990, 24, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO and UNICEF. Child Labour and Domestic Work. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/ipec/areas/Childdomesticlabour/lang––en/index.htm (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Ansell, N.; van Blerk, L. Children’s Migration as a Household/Family Strategy: Coping with AIDS in Lesotho and Malawi. J. South. Afr. Stud. 2004, 30, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdillon, M. Children as domestic employees: Problems and promises. J. Child. Poverty 2009, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, I. Independent Child Migration and Education in Ghana. Develop. Change 2007, 38, 911–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.; Presler-Marshall, E.; Emirie, G.; Tefera, B. Rethinking the future-seeking narrative of child migration: The case of Ethiopian adolescent domestic workers in the Middle East. Afri. Black Diaspora 2018, 11, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Blerk, L. Livelihoods as Relational Im/mobilities: Exploring the Everyday Practices of Young Female Sex Workers in Ethiopia. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geograph. 2016, 106, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. Formalizing Domestic Work; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_559854.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- ILO. Practical Guide to Ending Child Labour and Protecting Young Workers in Domestic Work; Fundamental Principles and Rights at work Branch (FUNDAMENTALS); ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/ipec/Informationresources/WCMS_IPEC_PUB_30476/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Mehran, F. ILO Survey on Domestic Workers: Preliminary Guidelines; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Blagbrough, J. Child Domestic Labour: A Global Concern, in Child Slavery Now: A Contemporary Reader; Craig, G., Ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2020; pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pankhurst, A.; Crivello, G.; Tiumelissan, A. Children’s Work in Family and Community Contexts: Examples from Young Lives Ethiopia, in Working Paper 147. 2016. Young Lives. Available online: https://www.younglives.org.uk/sites/www.younglives.org.uk/files/YL-WP147-Childrens%20work%20in%20family%20and%20community%20contexts.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Baum, N. Girl Domestic Labour in Dhaka: Betrayal of Trust. In Working Boys and Girls at Risk: Child Labour in Urban Bangladesh; Lieten, G.K., Ed.; University Press: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Domestic Workers across the World: Global and Regional Statistics and the Extent of Legal Protection; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_173363.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Alem, A.; Zergaw, A.; Kebede, D.; Araya, M.; Desta, M.; Muche, T.; Chali, D.; Medhin, G. Child labor and childhood behavioral and mental health problems in Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 2000, 20, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Benvegnú, L.A.; Fassa, A.G.; Facchini, L.A.; Wegman, D.H.; Dall’Agnol, M.M. Work and behavioural problems in children and adolescents. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Watch. Lonely Servitude: Child Domestic Labor in Morocco. Human Rights Watch. 2012. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/11/15/lonely-servitude/child-domestic-labor-morocco (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Erulkar, A. Child Domestic Work and Transitions to Commercial Sexual Exploitation: Evidence from Ethiopia. 2018. Population Council. Available online: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-pgy/450/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Olsson, J.; Höjer, S.; Nyström, L.; Emmelin, M. Orphanhood and mistreatment drive children to leave home—A study from early AIDS–affected Kagera region, Tanzania. Int. Soc. Work 2017, 60, 1218–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, K.; Cappetta, A.; Ahn, R.; Macias-Konstantopoulos, W. Sex and Labor Trafficking in Paraguay: Risk Factors, Needs Assessment, and the Role of the Health Care System. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 886260518788364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.R.; Bharati, P.; Vasulu, T.S.; Chakrabarty, S.; Banerjee, P. Whole time domestic child labor in metropolitan city of Kolkata. Indian Pediatr. 2008, 45, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gamlin, J.; Camacho, A.Z.; Ong, M.; Hesketh, T. Is domestic work a worst form of child labour? The findings of a six–country study of the psychosocial effects of child domestic work. Child. Geogr. 2015, 13, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesketh, T.M.; Gamlin, J.; Ong, M.; Camacho, A.Z.V. The psychosocial impact of child domestic work: A study from India and the Philippines. Arch. Dis. Child. 2012, 97, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagbrough, J. They Respect Their Animals More: Voices of child domestic workers; Anti–Slavery International: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G. Child Labor & Educational Disadvantage—Breaking the Link, Building Opportunity: A Review by Gordon Brown. 2012. UN Special Envoy for Global Education. Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/child-labor-educational-disadvantage-breaking-link-building-opportunity-review-gordon-brown (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- ILO. Give Girls A Chance. Tackling Child Labour, A Key to the Future; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thi, M.A.; Ranganathan, M.; Pocock, N.; Zimmerman, C. Employers of Child Domestic Workers in Myanmar. A Scoping Study; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ASI. Home Truths: Wellbeing and vulnerabilities of child domestic workers; Anti–Slavery International: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and health developmental education and economic outcomes of child domestic workers: Overarching rapid reviews protocol, in PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. 2019. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/review_scope.asp (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Pocock, N.S.; Chan, C.W.; Zimmerman, C. Suitability of Measurement Tools for Assessing the Prevalence of Child Domestic Work: A Rapid Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covarrubias, K.; Davis, B.; Winters, P. From protection to production: Productive impacts of the Malawi Social Cash Transfer scheme. J. Dev. Eff. 2012, 4, 50–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismayilova, L.; Karimli, L.; Sanson, J.; Gaveras, E.; Nanema, R.; Tô-Camier, A.; Chaffin, J. Improving mental health among ultra–poor children: Two–year outcomes of a cluster–randomized trial in Burkina Faso. Soc. Sc. Med. 2018, 208, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimli, L.; Rost, L.; Ismayilova, L. Integrating Economic Strengthening and Family Coaching to Reduce Work–Related Health Hazards Among Children of Poor Households: Burkina Faso. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 62, S6–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, L.; Seff, I.; Assezenew, A.; Eoomkham, J.; Falb, K.; Ssewamala, F.M. Effects of a Social Empowerment Intervention on Economic Vulnerability for Adolescent Refugee Girls in Ethiopia. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 62, S15–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engebretsen, S.B. Endline Findings of Filles Éveillées (Girls Awakened): A Pilot Program for Migrant Adolescent Girls in Domestic Service. Cohort 1 (2011–2012), Bobo Dioulasso; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Engebretsen, S. Evaluation of Filles Eveilles (Girls Awakened): A Pilot Program for Migrant Adolescent Girls in Domestic Service; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Erulkar, A.; Ferede, A.; Girma, W.; Ambelu, W. Evaluation of “Biruh Tesfa” (Bright Future) program for vulnerable girls in Ethiopia. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies 2013, 8, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erulkar, A.; Medhin, G. Educational and Health Service Utilization Impacts of Girls’ Safe Spaces Program in Addis Ababa, Ethopia; Population Council: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, K. Learning Skills, Building Social Capital, and Getting an Education: Actual and Potential Advantages of Child Domestic Work in Bangladesh. Laboring Learn. 2017, 10, 305–325. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, L.; Pocock, N.S.; Naisanguansri, V.; Suos, S.; Dickson, B.; Thuy, D.; Koehler, J.; Sirisup, K.; Pongrungsee, N.; Nguyen, V.A.; et al. Health of men, women, and children in post–trafficking services in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam: An observational cross–sectional study. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e154–e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emberson, C.; Bhriain, N.; Wyman, E. Protecting Child Domestic Workers in Tanzania: Evaluating the Scalability and Impact of the Drafting and Adoption of Local District Bylaws; University of Nottingham: Nottingham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Black, M. Child Domestic Workers: Finding a Voice. A Handbook on Advocacy; Anti–Slavery International: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Klocker, N. Struggling with child domestic work: What can a postcolonial perspective offer? Child. Geogr. 2014, 12, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ravololomanga, B.; Schlemmer, B. ’Unexploited’ Labour: Social Transition in Madagascar. In The Exploited Schold; Schlemmer, B., Ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2000; pp. 300–314. [Google Scholar]

| Author (Year) | Intervention | Country | Study Design | Study Population | Sampling Method | Outcome | Disaggregated Outcomes for CDWs | Study Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karimli et al. (2018) a [37] | Trickle Up and Trickle Up Plus | Burkina Faso | Open-label cluster randomised design | Ultra-poor families (mothers and children) children aged 10–15 | Random selection | Health and social | No | Moderate |

| Ismayilova et al. (2018) a [36] | Trickle Up and Trickle Up Plus | Burkina Faso | Open-label cluster randomised design | Ultra-poor families (mothers and children) children aged 10–15 | Random selection | Health and social | No | Good |

| Erulkar (2013) b [41] | Biruh Tesfa | Ethiopia | Quasi-experimental (pre and post intervention in control and intervention areas) | Vulnerable girls and adolescents aged 10–19 | Purposive | Health and social | No | Moderate |

| Erulkar and Medhin (2014) b [42] | Powering Up Biruh Tesfa | Ethiopia | Quasi-experimental (pre and post intervention in control and intervention areas) | Vulnerable girls and adolescents aged 10–19 | Random selection from eligible girls | Educational | No | Moderate |

| Engrebretson (2012) c [39] | Filles Eveillees | Burkina Faso | Pre–post evaluation (no control) | Female adolescent migrant domestic workers aged 11–16 | Purposive | Health and social | Yes | Poor |

| Engrebretson (2013) c [40] | Filles Eveillees | Burkina Faso | Pre–post evaluation (no control) | Female adolescent migrant domestic workers aged 11–18 | Purposive | Health and social | Yes | Poor |

| Covarrubius (2012) [35] | Malawi Social Cash Transfer Programme | Malawi | Open-label cluster randomised design | Children from impoverished households eligible for participation in Malawi’s social cash transfer programme aged <18 | Villages randomly assigned, households assigned using criterion sampling | Prevalence | Yes | Poor |

| Stark (2018) [38] | COMPASS (Creating Opportunities through Mentoring, Parental Involvement, and Safe Spaces) | Ethiopia | Randomised controlled trial | Vulnerable adolescent refugees from surrounding conflict-affected regions mainly in Sudan and South Sudan aged 13–19 | Random assignment | Economic | No | Moderate |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kyegombe, N.; Pocock, N.S.; Chan, C.W.; Blagbrough, J.; Zimmerman, C. Evaluations of Interventions with Child Domestic Workers: A Rapid Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910084

Kyegombe N, Pocock NS, Chan CW, Blagbrough J, Zimmerman C. Evaluations of Interventions with Child Domestic Workers: A Rapid Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910084

Chicago/Turabian StyleKyegombe, Nambusi, Nicola S. Pocock, Clara W. Chan, Jonathan Blagbrough, and Cathy Zimmerman. 2021. "Evaluations of Interventions with Child Domestic Workers: A Rapid Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910084

APA StyleKyegombe, N., Pocock, N. S., Chan, C. W., Blagbrough, J., & Zimmerman, C. (2021). Evaluations of Interventions with Child Domestic Workers: A Rapid Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910084