A Tale of Two Solitudes: Loneliness and Anxiety of Family Caregivers Caring in Community Homes and Congregate Care

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Family Caregiving Work, Anxiety, and Distress

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Assessments

2.2. Qualitative Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Qualitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics and Caregiving Situations

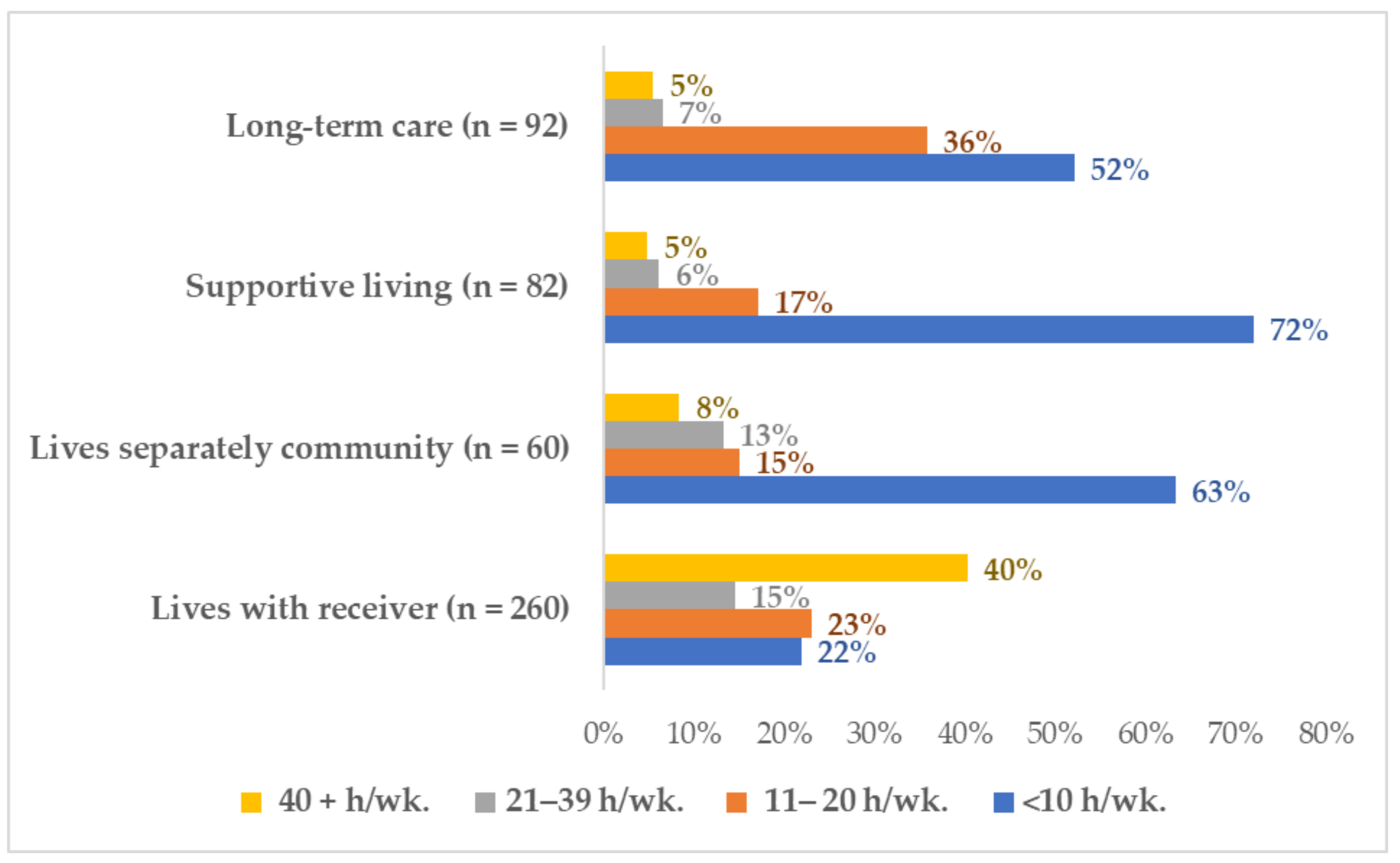

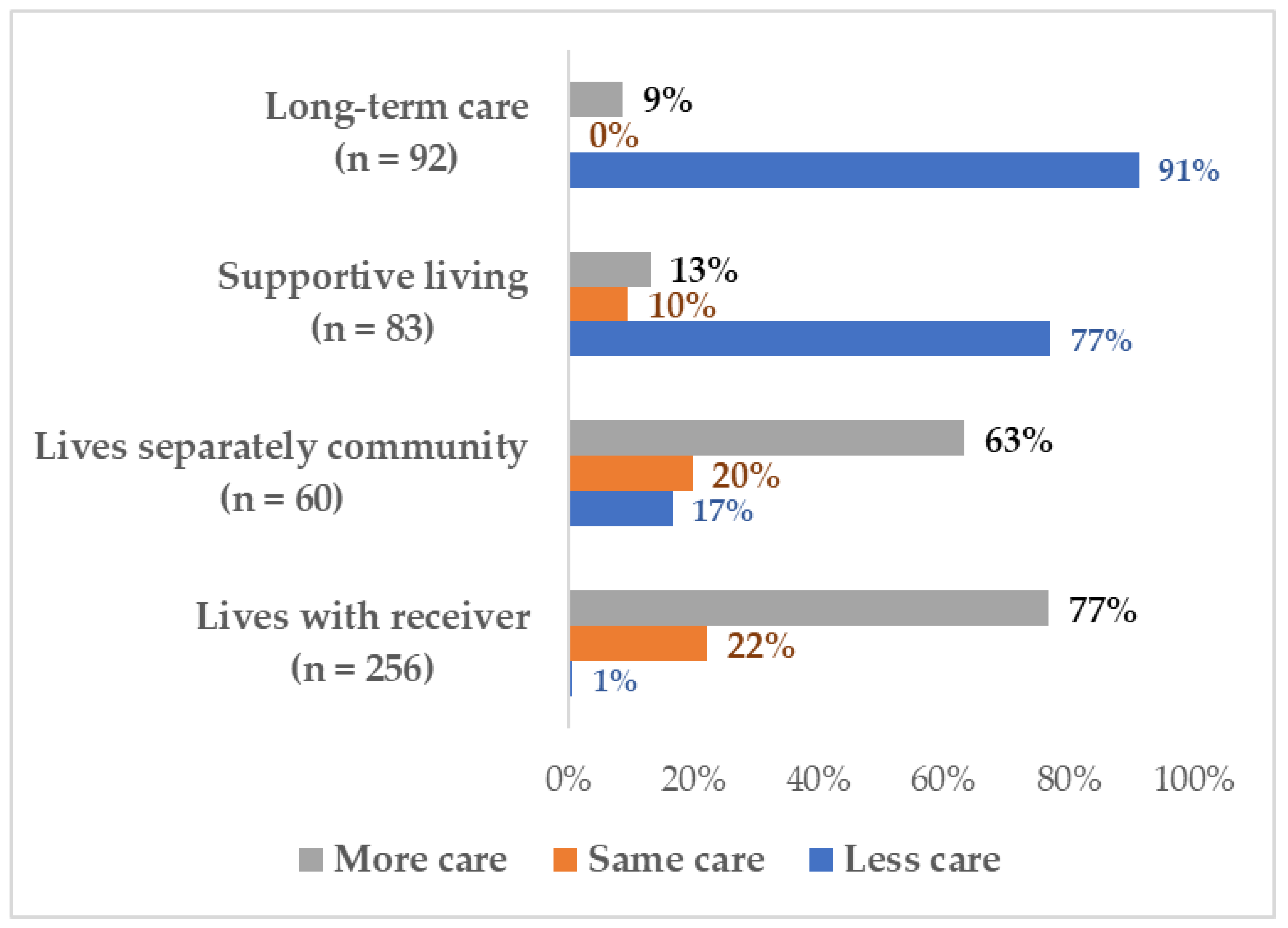

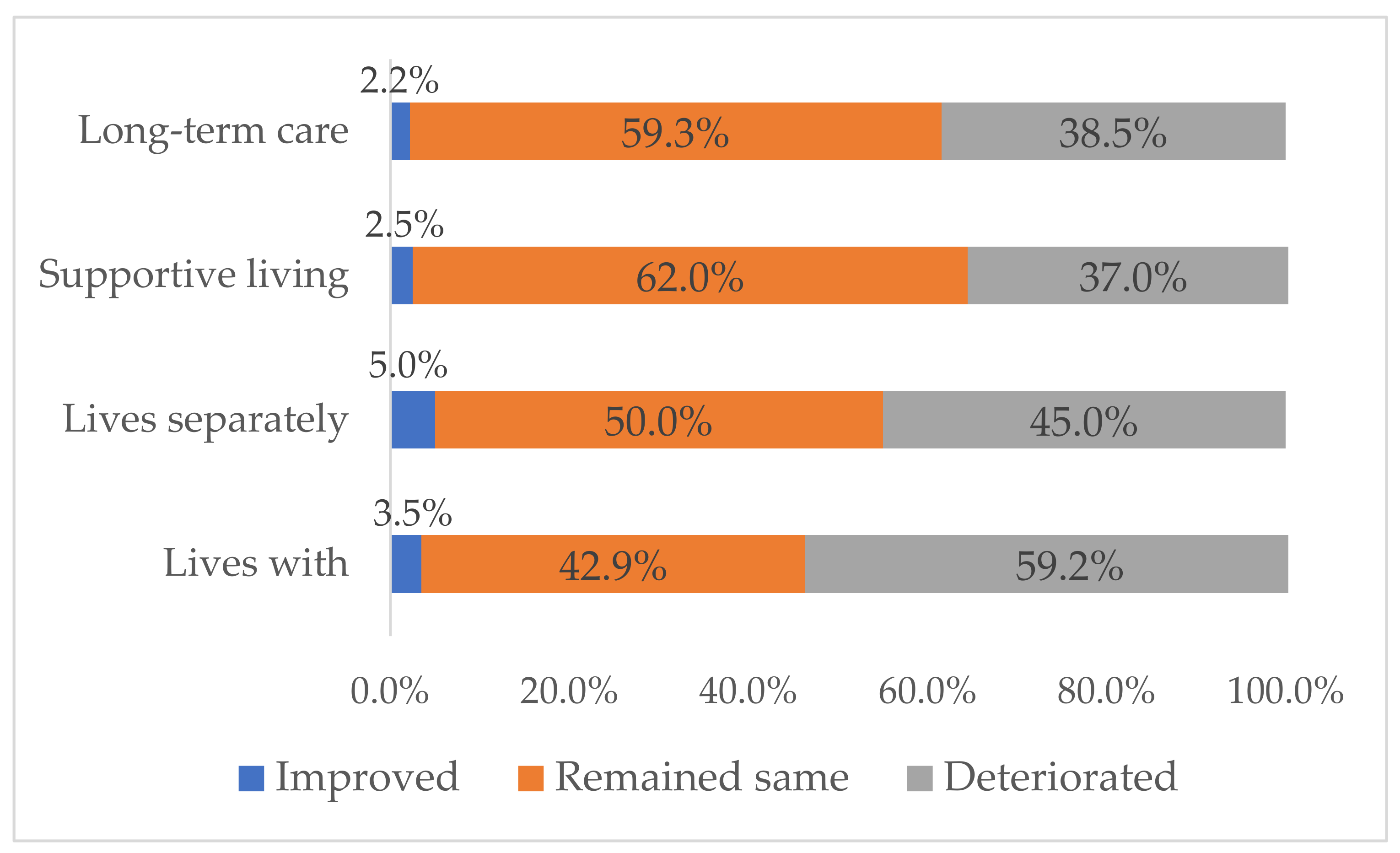

3.2. Changes in Family Caregivers Care Work: Two Solitudes

3.3. Prevalence of Anxiety and Loneliness

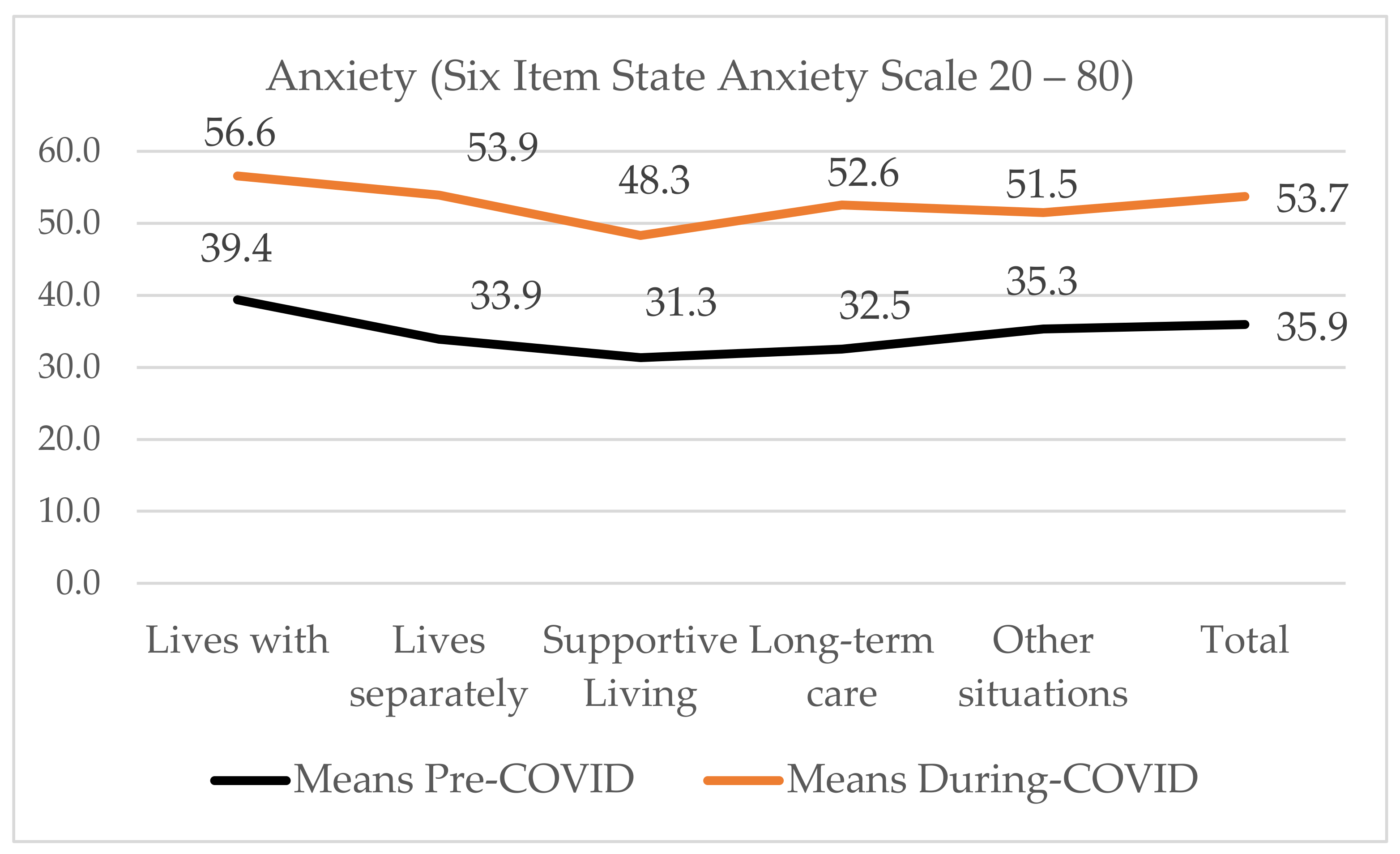

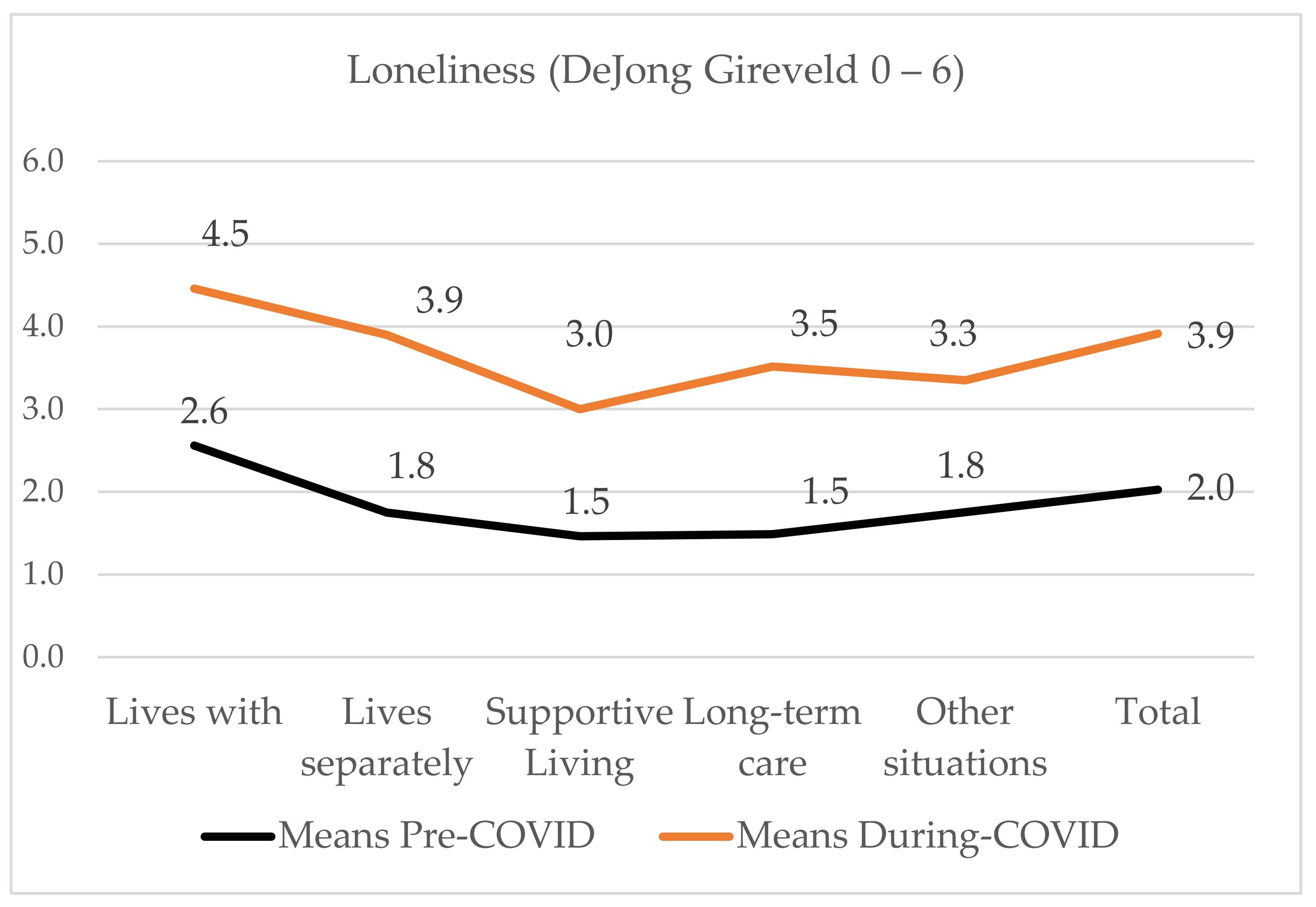

3.4. Impact of COVID-19 on Anxiety and Loneliness

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Canada. Caregivers in Canada 2018. 2020. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200108/dq200108a-eng.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2020).

- Shereen, M.A.; Khan, S.; Kazmi, A.; Bashir, N.; Siddique, R. COVID-19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 24, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stall, N.M.; Johnstone, J.; McGeer, A.J.; Dhuper, M.; Dunning, J.; Sinha, S.K. Finding the right balance: An evidence-informed guidance document to support the re-opening of Canadian nursing homes to family caregivers and visitors during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1365–1370.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stall, N.; Keresteci, M.; Rochon, P. Family caregivers will be key during the COVID-19 pandemic. Toronto Star, 31 March 2020. Available online: https://www.thestar.com/opinion/contributors/2020/03/31/family-caregivers-will-be-key-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.html(accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Rosalind Carter Institute. Caregivers in Crisis: A Report on the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health and Well-Being of Caregivers; Rosalind Carter Institute for Caregiving: Americus, GA, USA, 2020; p. 46. Available online: https://www.rosalynncarter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Caregivers-in-Crisis-Report-October-2020-10-22-20.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Carers UK. Caring behind Closed Doors: Forgotten Families in the Coronavirus Outbreak. 2020, Volume 30. Available online: https://www.carersuk.org/for-professionals/policy/policy-library?task=download&file=policy_file&id=7035 (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- Schulz, R.; Beach, S.R.; Czaja, S.J.; Martire, L.M.; Monin, J.K. Family caregiving for older adults. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2020, 71, 635–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilapil, M.; Coletti, D.J.; Rabey, C.; De Laet, D. Caring for the caregiver: Supporting families of youth with special health care needs. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2017, 47, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, S.K. Why the elderly could bankrupt Canada and how demographic imperatives will force the redesign of acute care service delivery. Healthc. Pap. 2011, 11, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qualls, S.H. Caregiving Families Within the long-term services and support system for older adults. Am. Psychol. 2016, 71, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Konietzny, C.; Kaasalainen, S.; Dal-Bello, H.V.; Merla, C.; Te, A.; Di Sante, E.; Kalfleish, L.; Hadjistavropoulos, T. Muscled by thesystem: Informal caregivers’ experiences of transitioning an older adult into long-term care. Can. J. Aging 2018, 37, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Comas-Herrera, A.; Zalakaín, J.; Litwin, C.; Hsu, A.T.; Lane, N.; Fernández, J.L. Mortality Associated with COVID-19 Outbreaks in Care Homes: Early International Evidence; Article in LTCcovid.org, International Long-Term Care Policy Network, CPEC-LSE. 1 February 2021. Available online: https://ltccovid.org/2020/04/12/mortality-associated-with-covid-19-outbreaks-in-care-homes-early-international-evidence/ (accessed on 27 June 2020).

- Sepulveda, E.R.; Stall, N.M.; Sinha, S.K. A comparison of COVID-19 mortality rates among long-term care residents in 12 OECD countries. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1572–1574.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, M.; Statscan. Portrait of Caregivers 2012. 2013. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-652-x/89-652-x2013001-eng.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2015).

- Statscan. Care counts: Caregivers in Canada, 2018. 2020. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2020001-eng.htm (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Health Quality Ontario. The Reality of Caring: Distress among Caregivers of Homecare Patients. 2016. Available online: https://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/system-performance/reality-caring-report-en.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Mackenzie, I. Caregivers in Distress: A growing Problem. 30 August 2017. Office of the Seniors’ Advocate BC. Available online: https://www.seniorsadvocatebc.ca/osa-reports/caregivers-in-distress-a-growing-problem-2/#:~:text=The%20report%2C%20Caregivers%20in%20Distress,continue%20with%20their%20caregiving%20duties (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Canadian Institutes of Health Information. Supporting Informal Caregivers: The Heart of Home Care 2010. Available online: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/Caregiver_Distress_AIB_2010_EN.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Fast, C.T.; Houlihan, D.; Buchanan, J.A. Developing the family involvement questionnaire-long-term care: A measure of familial involvement in the lives of residents at long-term care facilities. Gerontologist 2019, 59, E52–E55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M.S.I.; Ursúa, M.P.; Caperos, J.M. The family caregiver after the institutionalization of the dependent elderly relative. Educ. Gerontol. 2017, 43, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.; Horowitz, J.M.; Bell, J.; Livingston, G.; Schwarzer, S.; Patten, E. Family Support in Graying Societies: How Americans, Germans and Italians Are Coping with an Aging Population. 2015. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/05/2015-05-21_family-support-relations_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Pauley, T.; Chang, B.W.; Wojtak, A.; Seddon, G.; Hirdes, J. Predictors of caregiver distress in the community setting using the home care version of the resident assessment instrument. Prof. Case Manag. 2018, 23, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Yateem, N.; Brenner, M. Validation of the short state trait anxiety inventory (Short STAI) completed by parents to explore anxiety levels in children. Compr. Child. Adolesc. Nurs. 2017, 40, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abzhandadze, T.; Forsberg-Wärleby, G.; Holmegaard, L.; Redfors, P.; Jern, C.; Blomstrand, C.; Jood, K. Life satisfaction in spouses of stroke survivors and control subjects: A 7-year follow-up of participants in the sahlgrenska academy study on ischaemic stroke. J. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 49, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Petriwskyj, A.; Parker, D.; O′Dwyer, S.; Moyle, W.; Nucifora, N. Interventions to build resilience in family caregivers of people living with dementia: A comprehensive systematic review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2016, 14, 238–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, C.C.; Hsu, B.; Cumming, R.G.; Blyth, F.M.; Waite, L.M.; Le Couteur, D.G.; Handelsman, D.J.; Naganathan, V. Caregiving and all-cause mortality in older men 2005–2015: The Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano-Toledano, F.; de la Rubia, J.M. Factors associated with anxiety in family caregivers of children with chronic diseases. BioPsychoSocial Med. 2018, 12, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ugalde, A.; Krishnasamy, M.; Schofield, P. The relationship between self-efficacy and anxiety and general distress in caregivers of people with advanced cancer. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 939–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, G.; Kuh, D.; Hotopf, M.; Stafford, M.; Richards, M. Association between lifetime affective symptoms and premature mortality. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, A.; Khatiban, M.; Mollai, Z.; Mohammadi, Y. Effect of informational support on anxiety in family caregivers of patients with hemiplegic stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 29, 105020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfe, M.; O′Brien, K.M.; Timmons, A.; Butow, P.; O′Sullivan, E.; Gooberman-Hill, R.; Sharp, L. Informal caregiving in head and neck cancer: Caregiving activities and psychological well-being. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denno, M.S.; Gillard, P.J.; Graham, G.D.; Dibonaventura, M.D.; Goren, A.; Varon, S.F.; Zorowitz, R. Anxiety and depression associated with caregiver burden in caregivers of stroke survivors with spasticity. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 1731–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guay, C.; Auger, C.; Demers, L.; Mortenson, W.B.; Miller, W.C.; Gélinas-Bronsard, D.; Ahmed, S. Components and outcomes of internet-based interventions for caregivers of older adults: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Li, C.; Shi, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Yu, T.; Ji, Y. Caregiver burden and prevalence of depression, anxiety and sleep disturbances in Alzheimer′s disease caregivers in China. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeher, K.; Low, L.F.; Reppermund, S.; Brodaty, H. Predictors and outcomes for caregivers of people with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic literature review. Alzheimer Dement. 2013, 9, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaddour, L.; Kishita, N. Anxiety in informal dementia carers: A meta-analysis of prevalence. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2020, 33, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Jong, G.J.; Keating, N.; Fast, J.E. Determinants of loneliness among older adults in Canada. Can. J. Aging 2015, 34, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourassa, K.J.; Sbarra, D.A.; Whisman, M.A. Women in very low quality marriages gain life satisfaction following divorce. J. Fam. Psychol. 2015, 29, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perissinotto, C.; Holt-Lunstad, J.; Periyakoil, V.S.; Covinsky, K. A Practical approach to assessing and mitigating loneliness and isolation in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtorta, N.K.; Kanaan, M.; Gilbody, S.; Ronzi, S.; Hanratty, B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart 2016, 102, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, G.O.; Thayer, C.E. Loneliness and Social Connections: A Survey of Adults 45 and Older; American Association of Retired Persons: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/life-leisure/2018/loneliness-social-connections-2018.doi.10.26419-2Fres.00246.001.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2020).

- Victor, C.R.; Rippon, I.; Quinn, C.; Nelis, S.M.; Martyr, A.; Hart, N.; Lamont, R.; Clare, L. The prevalence and predictors of loneliness in caregivers of people with dementia: Findings from the IDEAL programme. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 25, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harvey, L.A. REDCap: Web-based software for all types of data storage and collection. Spinal Cord 2018, 56, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tluczek, A.; Henriques, J.B.; Brown, R.L. Support for the reliability and validity of a six-item state anxiety scale derived from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. J. Nurs. Meas. 2009, 17, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marteau, T.M.; Bekker, H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1992, 31 Pt 3, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlan, L.; Savik, K.; Weinert, C. Development of a shortened State anxiety scale from the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) for patients receiving mechanical ventilatory support. J. Nurs. Meas. 2003, 11, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, G.J.; Van Tilburg, T. A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness—Confirmatory tests on survey data. Res. Aging 2006, 28, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokkema, T.; Naderi, R. Differences in late-life loneliness: A comparison between Turkish and native-born older adults in Germany. Eur. J. Ageing 2013, 10, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicolaisen, M.; Thorsen, K. Who are lonely? Loneliness in different age groups (18–81 years old), using two measures of loneliness. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2014, 78, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schulz, R.; Eden, J. Families Caring for an Aging America; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarit, S.H. Past is prologue: How to advance caregiver interventions. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarit, S.H.; Femia, E.E.; Kim, K.; Whitlatch, C.J. The structure of risk factors and outcomes for family caregivers: Implications for assessment and treatment. Aging Ment. Health 2010, 14, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, K.O.; Kurzawa, C.; Daly, B.; Prince-Paul, M. Identifying and addressing family caregiver anxiety. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2019, 21, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Dorstyn, D.; Ward, L.; Prentice, S. Alzheimers′ disease and caregiving: A meta-analytic review comparing the mental health of primary carers to controls. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, H.; Qing, Y.; Lingna, K.; Luanjiao, H.; Lingqiong, Z.; Hu, P.; Yang, Q.; Kong, L.; Hu, L.; Zeng, L. Relationship between the anxiety/depression and care burden of the major caregiver of stroke patients. Medicine 2018, 97, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinn, C.-L.J.; Betini, R.S.D.; Wright, J.; Eckler, L.; Chang, B.W.; Hogeveen, S.; Turcotte, L.; Hirdes, J.P. Adverse Events in Home Care: Identifying and responding with interRAI scales and clinical assessment protocols. Can. J. Aging Rev. Can. Vieil. 2018, 37, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russell, B.S.; Hutchison, M.; Tambling, R.; Tomkunas, A.J.; Horton, A.L. Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: Caregiver burden, mental Health, and the parent–child relationship. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2020, 51, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuijt, R.; Frost, R.; Wilcock, J.; Robinson, L.; Manthorpe, J.; Rait, G.; Walters, K. Life under lockdown and social restrictions—The experiences of people living with dementia and their carers during the COVID-19 pandemic in England. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consonni, M.; Telesca, A.; Bella, E.D.; Bersano, E.; Lauria, G. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients’ and caregivers′ distress and loneliness during COVID-19 lockdown. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carers UK. Alone and Caring: Isolation, Loneliness, and Impact of Caring on Relationships. 2015. Available online: https://www.carersuk.org/for-professionals/policy/policy-library?task=download&file=policy_file&id=5100 (accessed on 24 January 2020).

- Herklots, H. ‘Caring Alone’, Alone in the Crowd: Loneliness and Diversity; Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation: Lisbon, Portugal, 2014; pp. 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Talari, K.; Goyal, M. Retrospective studies—Utility and caveats. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2020, 50, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, A.Z.; Tan, J.S.; Zhang, M.W.; Ho, R.C. The global prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among caregivers of stroke survivors. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokorelias, K.M.; Naglie, G.; Gignac, M.A.M.; Rittenberg, N.; Cameron, J.I. A qualitative exploration of how gender and relationship shape family caregivers’ experiences across the Alzheimer’s disease trajectory. Dementia 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, K.L.; Robertson, N. Coping with caring for someone with dementia: Reviewing the literature about men. Aging Ment. Health 2008, 12, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygouri, I.; Cowdell, F.; Ploumis, A.; Gouva, M.; Mantzoukas, S. Gendered experiences of providing informal care for older people: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Beach, S.R.; Friedman, E.M.; Martsolf, G.R.; Rodakowski, J.; James, A.E. Changing structures and processes to support family caregivers of seriously ill patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, S36–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roth, D.L.; Brown, S.L.; Rhodes, J.D.; Haley, W.E. Reduced mortality rates among caregivers: Does family caregiving provide a stress-buffering effect? Psychol. Aging 2018, 33, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, D.L.; Fredman, L.; Haley, W.E. Informal caregiving and its impact on health: A reappraisal from population-based studies. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Caregiver age | 604 |

| 15–34 years | 30 (5.0) |

| 35–54 years | 147 (24.4) |

| 55–64 years | 211 (34.9) |

| 65–74 years | 154 (25.5) |

| 75+ years Prefer not to answer | 43 (7.1) 19 (3.1) |

| Caregiver sex | |

| Male | 84 (13.9) |

| Female | 488 (80.8) |

| Other Prefer not to answer | 2 (0.3) 30 (5.0) |

| Care hours before COVID-19 | |

| <less 10 h per week | 255 (42.6) |

| 11–20 h per week | 142 (23.5) |

| 21–39 h per week 40+ h per week Prefer not to answer | 68 (11.3) 133 (22.0) 6 (1.0) |

| Changes in care since COVID-19 | |

| More care | 299 (50) |

| Same amount of care | 96 (16.1) |

| Less care | 203 (33.9) |

| Prefer not to answer | 6 (1.0) |

| Care hours since COVID-19 | |

| Less care | 203 (34.1) |

| Same Amount of care | 96 (16.1) |

| 10 or less more hours per week | 127 (21.3) |

| 11–20 more hours per week | 59 (15.2) |

| 21–39 more hours per week | 31 (5.1) |

| 40+ more hours per week | 79 (13.3) |

| Prefer not to answer | 9 (2.0) |

| Caregivers’ physical health during COVID-19 | |

| Improved Remained stable | 25 (4.1) 284 (47.0) |

| Deteriorated | 283 (46.9) |

| Prefer not to answer | 12 (2.0) |

| Caregivers’ mental health during COVID-19 | |

| Improved Remained stable | 11 (1.8) 237 (39.2) |

| Deteriorated | 339 (56.1) |

| Prefer not to answer | 17 (2.9) |

| Number of people cared for | 4 |

| 1 person | 367 (72.5) |

| 2 people | 102 (20.2) |

| 3 or more people | 37 (7.3) |

| Prefer not to answer | 98 (16.2) |

| Care receiver’s age | |

| Birth to-34 years | 68 (11.3) |

| 35–54 years | 24 (4.0) |

| 55–64 years | 30 (5.0) |

| 65–74 years | 80 (13.2) |

| 75+ years | 259 (42.9) |

| Prefer not to answer | 143 (23.7) |

| Care receiver’s living situation | |

| Same home/Lives with caregiver | 262 (43.4) |

| Separate home/Condo/Apartment | 60 (9.9) |

| Supportive/Assisted Living/Lodges | 84 (13.9) |

| Long-term care | 92 (15.5) |

| Other (two or more settings) | 94 (15.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 12 (2.0) |

| Severity of receiver’s health condition | |

| Severe | 105 (17.4) |

| Mild/moderate | 121 (20.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 378 (62.6) |

| <10 h/wk. | 11–20 h/wk. | 21–39 h/wk. | 40+ h/wk. | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Lives with receiver | 57 | 9.7 | 60 | 10.2 | 38 | 6.5 | 105 | 19.9 | 260 | 44.3 |

| Lives separately community | 38 | 6.5 | 9 | 1.5 | 8 | 1.4 | 5 | 0.9 | 60 | 10.2 |

| Supportive living | 59 | 10.1 | 14 | 2.4 | 5 | 0.9 | 4 | 0.7 | 82 | 14.2 |

| Long-term care | 48 | 8.2 | 33 | 5.6 | 6 | 1.0 | 5 | 0.9 | 92 | 15.7 |

| Other | 49 | 8.3 | 23 | 3.9 | 10 | 1.7 | 11 | 1.9 | 93 | 15.8 |

| Total | 251 | 42.8 | 139 | 12.7 | 67 | 11.4 | 130 | 22.1 | 587 | 100 |

| Less Care during COVID-19. | Same Care pre/during COVID-19. | <10 More h/wk. | 11–20 More h/wk. | 21+ More h/wk. | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Lives with receiver | 2 | 0.8 | 57 | 22.3 | 43 | 16.8 | 61 | 23.8 | 93 | 36.3 | 256 | 43.8 |

| Lives separately community | 10 | 16.7 | 12 | 20.0 | 16 | 26.7 | 15 | 25.0 | 7 | 11.7 | 60 | 10.3 |

| Supportive living | 64 | 77.1 | 8 | 9.6 | 10 | 12.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 83 | 14.2 |

| Long-term care | 84 | 91.3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4.3 | 3 | 3.3 | 1 | 1.1 | 92 | 15.8 |

| Other | 39 | 41.9 | 17 | 18.3 | 20 | 21.5 | 10 | 10.8 | 7 | 7.5 | 93 | 15.9 |

| Total | 199 | 34.1 | 94 | 16.1 | 93 | 15.9 | 90 | 15.4 | 108 | 18.5 | 584 | 100.0 |

| Living with | Living Separately | Supportive Living | Long-Term Care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Changes in family caregivers care work | |||

| This is much for difficult. The help I had developed is no longer able to assist. The few activities I had set up for my spouse are no longer available. On top of this, I also have my son with disabilities at home 24/7, as well. It feels like a dark hole, especially as both are cognitively impaired. The workload, the constant oversight and especially the lack of stimulation for me is really difficult now. Was trying to look for work and having interviews, but due to increase of care needed, and COVID-19, I am unbale to find work, and not qualified for any government financial help which adds to the current problems. | I am doing all the grocery shopping, prescription pick-ups, errands for my parents who are both in their 80’s to limit their community contacts. I’m feeling tired from all the extra assistance they need, but I would rather do this than increase their risk of community contact of COVID-19. I do not feel overburdened or anything. That’s quite a privilege. Yeah, personally, I feel like. I’m doing what a good daughter is supposed to do, because I do have friends who their parents are in care in a different community and talk to them once or twice a year. I just feel that I’m doing good. | At first, we talked on the phone regularly. It appeared as if he was doing well. When we started video chatting, it was very apparent how much my husband had gone downhill. He was always phoning me asking for things thinking that someone had stolen his stuff when he just couldn’t find it. I was unable to go help him get organized. He is on the second floor so difficult to see. It broke my heart to see him this week in an outside visit to see how much he has and I haven’t been there to help him. I am having health issues of my own I have been physically exhausted since my visit. | I can say with all honesty that after my mother was admitted to the long-term care facility and I could not visit, I could not sleep for the first 2+ weeks. I eventually had to use a prescribed sleep aid and sought the help of a psychologist as I simply could not stop thinking about my mother alone in a facility where she knew no one and she could not communicate her needs. Prior to COVID-19, I believe others would have considered me well adjusted, strong, resilient etc... I am saying these things, so that you would understand that I am not usually an anxious or nervous person. |

| Anxiety | |||

| It’s overwhelming especially since he has fallen into depression since the Day Program has closed for now. I feel like I am drowning. For the last 7 years, I have been alone in my care. I am exhausted and concerned. | Family and friends are less available Homecare is felt to not be an option as services have been ceased in a number of cases Ongoing personal anxiety and bouts of feeling low and overwhelmed. | She lives in a seniors’ lodge facility and it was too confusing for her with window visiting and when we were able to visit outside. It was also extremely hard on us (daughters) and affected our mental health. | I’ve had a few sleepless nights worrying about her and wondering if she feels abandoned and what brightens up her day. I visualize her sitting, restrained in her wheelchair, with none of the little pleasures we all take for granted to brighten up the day. |

| Loneliness | |||

| Isolated, on my own, support only by phone. Care is 24/7. I am getting less sleep. Self-care is nonexistent. | Social isolation placed more demand on me to be more emotionally, and socially available to my mother without any reprieve. Help from family and friends limited due to age and myriad of medical conditions of my mother. I feel inadequate. | Although I had peace of mind the staff were doing an awesome job at looking after my husband, it was difficult not knowing where my husband was mentally. Did he think I just abandoned him? Would he understand what was happening? I think we both are lonely. | My husband is placed in long-term [care]. Before I spent at least 4 days a week visiting, reading, walking, watching movies, playing games, going with him to activities. I miss being with him and I miss helping the other people and seeing their families. |

| Changes in family caregiver’s mental and physical health | |||

| I am getting desperate. I have no life, gave it up 20 years ago when dad got sick, now mother...I have no life of my own, I am tired mentally and physically. I’m definitely wondering if I’m losing my mind many days as the COVID-19 atmosphere and spending my days with a mate who has dementia. The lack of social connection has been detrimental for both of us. I do need respite but realize that is not possible now. Stress levels are high, and I’ve been short tempered with him. All family caregivers need someone to openly talk too, no judgment. | When you when you end up in a care role, as in my situation, the physical and mental health care toll on the caregiver is enormous. During COVID-19, I know I’ve aged 20 years and COVID-19 has a lot to say about that because of the extensive increase in the amount of things I’m expected to do. But again, you asked earlier “has anybody ever asked how you’re doing?” No, not even my siblings. Like, nobody cares. Caring for my mom is a privilege. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, she was very independent and now my sister and I do the grocery shopping and we share a meal once or twice a week. My relationship with my mother has improved. | No contact with mother and I am the only child. I was brought up by my mom only since I was 6 years old. Feel upset and isolated from mom. I feel helpless. Being an essential visitor, I find that staff leans on me more for her care. I am unable to look for work as I seem to be on call for the times they can’t get her to eat, take her meds, or calm her down. It has been extremely hard on my mental, physical, and financial health. My mom and I are closer than we have ever been because it is just her and I. I have learned so much about her family. The staff at the lodge have been very accommodating. | The facility staff has done a tremendous job in managing the pandemic, but I need to visit my wife as she is slowly fading away from me. It makes me so sad. The sadness affects my health too. When my husband was living at home in January, I provided care 24/7 all year long. Homecare allowed me 6 h a week of respite. When my husband was first placed in LTC on Feb 4th, I travelled an hour each way to see him 5 days a week. I was terribly burned out but wanted to ensure he felt safe. The COVID pandemic forced me to stay at home. Physically, I regained my strength, but it was mentally challenging not to be able to see my husband. |

| Anxiety Pre-COVID-19 | Anxiety during COVID-19 | Loneliness Pre-COVID-19 | Loneliness during COVID-19 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale 20–80 | Not Anxious | Anxious | Scale 20–80 | Not Anxious | Anxious | Scale 0–6 | Not Lonely | Lonely | Scale 0–6 | Not Lonely | Lonely | |

| Mean | n (%) | n (%) | Mean | n (%) | n (%) | Mean | n (%) | n (%) | Mean | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Lives with/Same home | 39.4 | 140 (56.9) | 106 (43.1) | 56.6 | 39 (15.4) | 215 (84.6) | 2.6 | 83 (32.9) | 169 (67.1) | 4.5 | 17 (6.7) | 238 (93.3) |

| Lives in separate home | 33.9 | 44 (73.3) | 16 (26.7) | 53.9 | 15 (25.9) | 43 (74.1) | 1.75 | 33 (55.0) | 27 (45.0) | 3.9 | 9 (15.0) | 51 (85.0) |

| Supportive living | 31.3 | 71 (86.6) | 11 (13.4) | 48.3 | 26 (32.9) | 53 (67.1) | 1.46 | 48 (60.0) | 32 (40.0) | 3.29 | 13 (16.3) | 67 (83.3) |

| Long-term care | 32.5 | 69 (78.4) | 19 (21.6) | 52.6 | 24 (27.3) | 64 (72.7) | 1.49 | 57 (64.8) | 31 (35.2) | 3.51 | 19 (21.3) | 70 (78.7) |

| Other | 35.3 | 64 (69.6) | 28 (30.4) | 51.5 | 17 (18.7) | 74 (81.3) | 1.8 | 44 (48.9) | 46 (51.1) | 3.3 | 23 (25.0) | 69 (75.0) |

| Total | 35.9 | 388 (68.3) | 180 (31.7) | 53.7 | 121 (21.2) | 449 (78.8) | 2.03 | 265 (46.5) | 305 (53.5) | 3.9 | 81 (14.1) | 495 (85.9) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anderson, S.; Parmar, J.; Dobbs, B.; Tian, P.G.J. A Tale of Two Solitudes: Loneliness and Anxiety of Family Caregivers Caring in Community Homes and Congregate Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910010

Anderson S, Parmar J, Dobbs B, Tian PGJ. A Tale of Two Solitudes: Loneliness and Anxiety of Family Caregivers Caring in Community Homes and Congregate Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910010

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnderson, Sharon, Jasneet Parmar, Bonnie Dobbs, and Peter George J. Tian. 2021. "A Tale of Two Solitudes: Loneliness and Anxiety of Family Caregivers Caring in Community Homes and Congregate Care" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910010

APA StyleAnderson, S., Parmar, J., Dobbs, B., & Tian, P. G. J. (2021). A Tale of Two Solitudes: Loneliness and Anxiety of Family Caregivers Caring in Community Homes and Congregate Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910010