The Particularities of Pharmaceutical Care in Improving Public Health Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

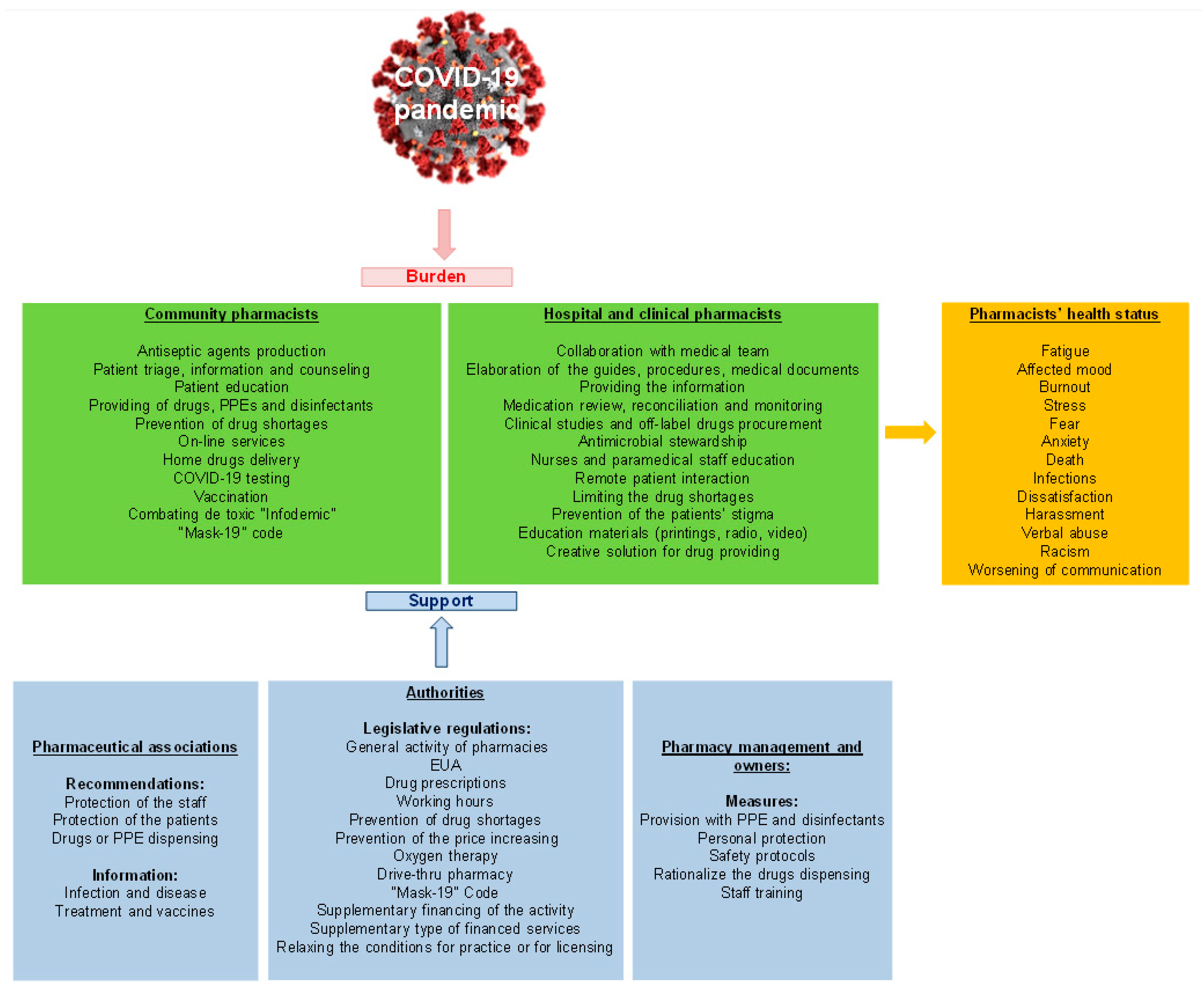

:1. Introduction

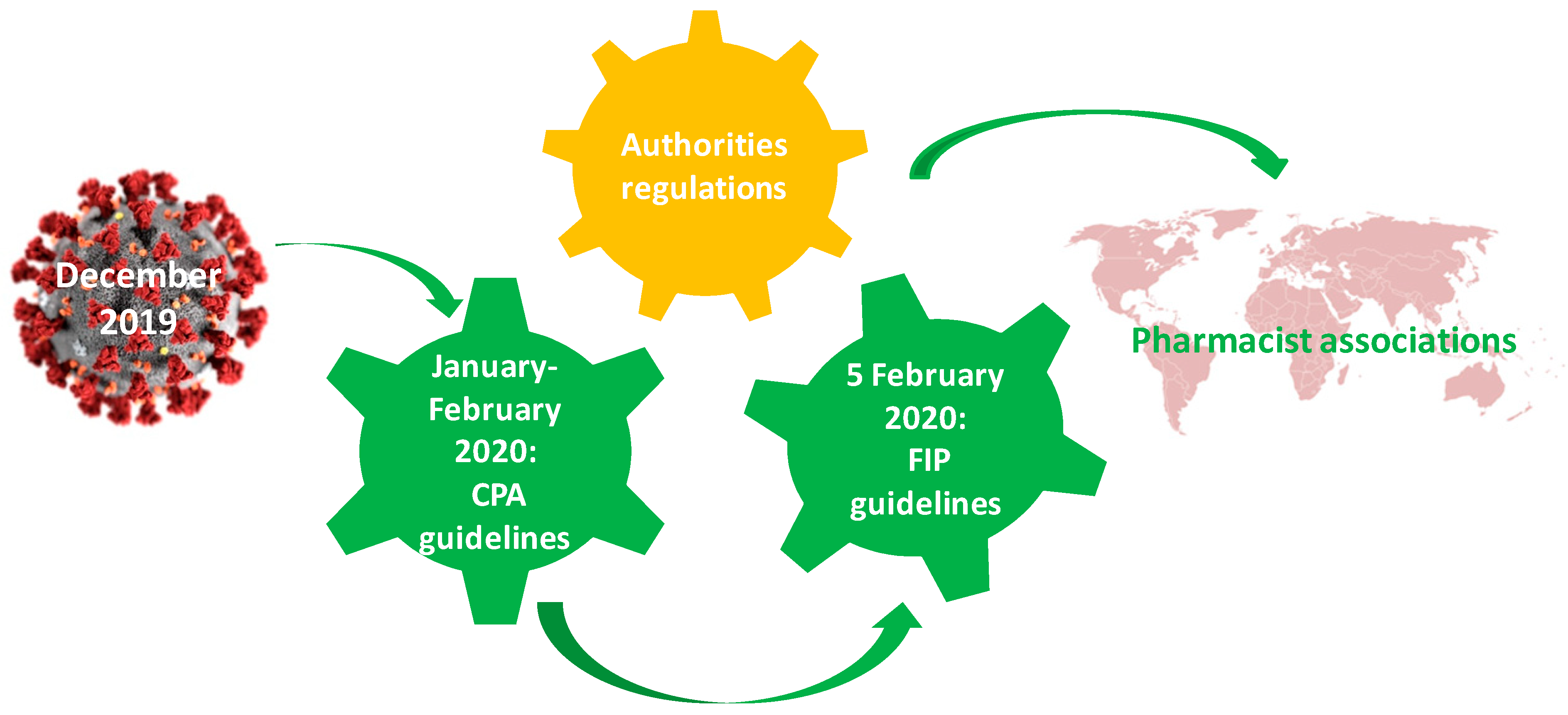

2. The Impact of the Authorities’ Decisions on Pharmaceutical Care

2.1. General Recommendations of the Authorities

2.2. Emergency Use Authorization

2.3. Regulations Regarding Drugs Prescriptions

2.4. Regulations of Working Hours

2.5. Legislative Regulations for Preventing Shortages or Drug Price Increases

- (i)

- the substitution of drugs with similar ones or dose adjustments were allowed for pharmacists from different countries (e.g., Australia, Belgium, Croatia, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, UK, etc.);

- (ii)

- in Denmark, health authorities demanded pharmacies to report the stock of critical medicine daily;

- (iii)

- (iv)

- limiting the drugs dispensed from the pharmacy was another legislative measure to prevent shortages. In Australia, the number of medical specialists that could initiate the treatment with hydroxychloroquine was restricted, or the quantity released off-label was of maximum one box/month/patient or one prescription/month/patient [14]. The Estonian Health Ministry limited the quantity of paracetamol to 2 boxes/patient [42]. The Saudi-Arabian Health Ministry limited the quantity of dietary supplements that boost the immune system to only one pack per customer to prevent the emergence of a black market for such items [45];

- (v)

- in Rwanda, the Ministry of Trade and Industry applied fines to pharmaceutical companies for increasing drug prices. In order to reduce price speculation and drug shortages, the authorities sent pharmacies a list of drugs in high demand, including their prices [43]. On the other hand, the healthcare insurance company from Croatia allowed pharmacies to dispense drugs with higher prices than the regulated ones, the difference being supported by health insurance. Also, these measures were enforced to solve drug shortages and limit the return of patients in pharmacies [35].

2.6. Oxygen Therapy

2.7. Drive-Thru Pharmacy

2.8. “Mask 19” Code

2.9. Financial Aspects Regarding the Pharmaceutical Services

3. The Involvement of the Professional Associations

- (i)

- PGEU elaborated some recommendations in order to protect the pharmacists and the patients, to ensure the optimal stocks, to identify and to report the suspected COVID-19 cases by pharmacists, to produce the hand disinfectants, to advise and inform the patients regarding different pathologies or treatment including COVID-19 ones, to deliver drugs at patients’ home. [64]. These recommendations were sent to pharmacists by means of the national professional organizations.

- (ii)

- The Croatian Pharmacy Chamber made specific recommendations for the pharmacists regarding safety measures, restrictions concerning the dispensation of specific drugs or PPE [23].

- (iii)

- In Serbia, the FIP guidelines were translated in the Serbian language by the Centre for Pharmacy and Biochemical Practice Development—University of Belgrade and the Pharmaceutical Chamber of Serbia [23].

- (iv)

- The official journal of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society from the UK (Pharmaceutical Journal) presented a material elaborated for pharmacies by CDC in order to help them manage the cold and flu during the COVID-19 pandemic [65].

- (v)

- The pharmacists’ association from Spain (Consejo General de Colegios Farmacéuticos) offered people correct information about COVID-19 vaccines, fought fake news and misinformation [66].

- (vi)

- The French Society for Oncological Pharmacy elaborated some recommendations in order to improve the pharmaceutical care for cancer patients during the pandemic. In addition to the general rules, during the pandemic, this guide contained some specific rules, such as (a) the pharmacy staff moves to other departments only when needed and the monitoring and the information will be collected remotely by using the telephone, online, by means of electronic files, etc., (b) the cytostatic production units have to be bio-cleaned under controlled atmosphere, (c) the gloves should be frequently changed; (d) injectable forms should be replaced with oral forms, if possible, (e) relocation of students in practice to the sections with deficient staff, (f) pharmacists have to monitor the stocks of glucocorticoids, anti-inflammatories or kinase inhibitors (drugs used experimentally in COVID-19), etc. [67].

- (vii)

- The American Society of Hospital Pharmacists gave patients 60-day free access to its own database with COVID-19 pathology and treatment [13].

- (viii)

- In Australia, authorities, together with the Pharmacy Guild of Australia and PSA, allowed the substitution of drugs with similar ones or dose adjustments by pharmacists when a prescribed drug was unavailable. Also, PSA supported the pharmacists in educating the population to encourage rational drug purchasing (even by drafting posters) [14].

- (ix)

- In Lebanon, the Order of Pharmacists elaborated some minimal guidance for community pharmacists [29].

4. Responsibilities of the Owners and Management of Pharmacies

5. COVID-19 Influences on Pharmacists’ Health Status

6. Pharmaceutical Care in Community Pharmacies

6.1. Production of the Antiseptic Agents

6.2. Patient’ Triage, Information and Counseling

6.3. Online Purchasing and Home Drug Delivery

6.4. COVID-19 Testing

6.5. Vaccine Administration

6.6. Combating the Toxic “Infodemic”

7. Specific Clinical and Hospital Pharmacy Services

7.1. Clinical Pharmacists’ Roles

7.2. Collaboration with the Medical Team

7.3. Remote Patient Interaction

7.4. Creative Solutions in Hospitals

7.5. Limiting Drug Shortages

8. Limitations of the Study

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watson, K.E.; Singleton, J.A.; Tippett, V.; Nissen, L.M. Defining pharmacists’ roles in disasters: A Delphi study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0227132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Qahtani, A.A. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): Emergence, history, basic and clinical aspects. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 2531–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huppert, L.A.; Matthay, M.A.; Ware, L.B. Pathogenesis of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 40, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hui, D.S.; Azhar, E.I.; Madani, T.A.; Ntoumi, F.; Kock, R.; Dar, O.; Ippolito, G.; Mchugh, T.D.; Memish, Z.A.; Drosten, C.; et al. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health—The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 91, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Listings of WHO’s Response to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- WHO. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard with Vaccination Data. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Hepler, C.D.; Strand, L.M. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 1990, 47, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Mil, J.W.F. Definitions of Pharmaceutical Care and Related Concepts. In The Pharmacist Guide to Implementing Pharmaceutical Care; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Morgovan, C.; Cosma, S.; Burta, C.; Ghibu, S.; Polinicencu, C.; Vasilescu, D. Measures to reduce the effects of the economic and financial crisis in pharmaceutical companies. Farmacia 2010, 58, 400–407. [Google Scholar]

- Turcu-Stiolica, A.; Bogdan, M.; Subtirelu, M.-S.; Meca, A.-D.; Taerel, A.-E.; Iaru, I.; Kamusheva, M.; Petrova, G. Influence of COVID-19 on Health-Related Quality of Life and the Perception of Being Vaccinated to Prevent COVID-19: An Approach for Community Pharmacists from Romania and Bulgaria. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Alkharfy, K.M.; Alrabiah, Z.; Alhossan, A. Saudi Arabia, pharmacists and COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragazzi, N.; Mansour, M.; Bonsignore, A.; Ciliberti, R. The Role of Hospital and Community Pharmacists in the Management of COVID-19: Towards an Expanded Definition of the Roles, Responsibilities, and Duties of the Pharmacist. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quteimat, O.M.; Amer, A.M. SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: How can pharmacists help? Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erku, D.A.; Belachew, S.A.; Abrha, S.; Sinnollareddy, M.; Thomas, J.; Steadman, K.J.; Tesfaye, W.H. When fear and misinformation go viral: Pharmacists’ role in deterring medication misinformation during the “infodemic” surrounding COVID-19. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1954–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, J.C.; Parkin, R. The challenges of COVID-19 for community pharmacists and opportunities for the future. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 37, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Declaration of Alma-Ata. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/policy-documents/declaration-of-alma-ata,-1978 (accessed on 20 June 2015).

- WHO. Constitution of the World Health Organization (Preamble). Available online: https://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2015).

- Cosma, S.A.; Bota, M.; Fleşeriu, C.; Morgovan, C.; Văleanu, M.; Cosma, D. Measuring patients’ perception and satisfaction with the Romanian healthcare system. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Europe Community Pharmacists Are Key Players in COVID-19 Response and Must Stay Up-To-Date on Guidance. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/5/community-pharmacists-are-key-players-in-covid-19-response-and-must-stay-up-to-date-on-guidance (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- CDC. Guidance for Pharmacies. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/pharmacies.html#print (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- ECDC. Europa COVID-19 Infection Prevention and Control Measures for Primary Care, Including General Practitioner Practices, Dental Clinics and Pharmacy Settings: First Update. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/covid-19-infection-prevention-and-control-primary-care (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Baratta, F.; Visentin, G.M.; Enri, L.R.; Parente, M.; Pignata, I.; Venuti, F.; Di Perri, G.; Brusa, P. Community pharmacy practice in italy during the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic: Regulatory changes and a cross-sectional analysis of seroprevalence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, H.; Tadić, I.; Falamić, S.; Ortner Hadžiabdić, M. Pharmacists’ role, work practices, and safety measures against COVID-19: A comparative study. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS. Standard Operating Procedure—Community Pharmacy. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/publication/standard-operating-procedure-community-pharmacy/ (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Graham, C. NHS England advises pharmacies to prepare “isolation space” for patients with suspected COVID-19. Pharm. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortajada-Goitia, B.; Morillo-Verdugo, R.; Margusino-Framiñán, L.; Marcos, J.A.; Fernández-Llamazares, C.M.; Goitia, B.T.; Clave, P. Survey on the situation of telepharmacy as applied to the outpatient care in hospital pharmacy departments in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic. Farm. Hosp. 2020, 44, 135–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atif, M.; Malik, I. COVID-19 and community pharmacy services in Pakistan: Challenges, barriers and solution for progress. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzingirai, B.; Matyanga, C.M.J.; Mudzviti, T.; Siyawamwaya, M.; Tagwireyi, D. Risks to the community pharmacists and pharmacy personnel during COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives from a low-income country. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeenny, R.M.; Ramia, E.; Akiki, Y.; Hallit, S.; Salameh, P. Assessing knowledge, attitude, practice, and preparedness of hospital pharmacists in Lebanon towards COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. Emergency Use Authorization for Vaccines Explained. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/emergency-use-authorization-vaccines-explained (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Aruru, M.; Truong, H.A.; Clark, S. Pharmacy Emergency Preparedness and Response (PEPR): A proposed framework for expanding pharmacy professionals’ roles and contributions to emergency preparedness and response during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1967–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Revokes Emergency Use Authorization for Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-revokes-emergency-use-authorization-chloroquine-and (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Singh, J.A.; Ravinetto, R. COVID-19 therapeutics: How to sow confusion and break public trust during international public health emergencies. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, F.A.; Lee, V.; Leite, S.N.; Murillo, M.D.; Menge, T.; Antoniou, S. Pharmacists reinventing their roles to effectively respond to COVID-19: A global report from the international pharmacists for anticoagulation care taskforce (iPACT). J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PGEU. Grup Position Paper on the Role of Community Pharmacists in COVID-19-Lessons Learned from the Pandemic. Available online: https://www.pgeu.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/PGEU-Position-Paper-on-on-the-Lessons-Learned-from-COVID-19-ONLINE.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Peckham, A.M.; Ball, J.; Colvard, M.D.; Dadiomov, D.; Hill, L.G.; Nichols, S.D.; Tallian, K.; Ventricelli, D.J.; Tran, T.H. Leveraging pharmacists to maintain and extend buprenorphine supply for opioid use disorder amid COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2021, 78, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinte, E.; Zehan, T.; Miclaus, G.F.; Sandor, N.I.; Vaida, D.; Vostinaru, S. Implication of pharmacists in Cluj County in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. Rom. J. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 13, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Portfolio Ministers. Ministers Department of Health Ensuring Continued Access to Medicines during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the-hon-greg-hunt-mp/media/ensuring-continued-access-to-medicines-during-the-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Elbeddini, A.; Hooda, N.; Yang, L. Role of Canadian pharmacists in managing drug shortage concerns amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. Pharm. J. 2020, 153, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgovan, C.; Ghibu, S.; Maria Juncan, A.; Liviu Rus, L.; Butucă, A.; Vonica, L.; Muntean, A.; Moş, L.; Gligor, F.; Olah, N. Nutrivigilance: A new activity in the field of dietary supplements. Farmacia 2019, 67, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, J.D.; Schwenk, H.T.; Chen, M.; Gaskari, S. Drug shortage and critical medication inventory management at a children’s hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 26, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, V.; Cadogan, C.; Fialová, D.; Henman, M.C.; Hazen, A.; Okuyan, B.; Lutters, M.; Stewart, D. Provision of clinical pharmacy services during the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences of pharmacists from 16 European countries. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwizeyimana, T.; Hashim, H.T.; Kabakambira, J.D.; Mujyarugamba, J.C.; Dushime, J.; Ntacyabukura, B.; Ndayizeye, R.; Adebisi, Y.A.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E. Drug supply situation in Rwanda during COVID-19: Issues, efforts and challenges. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2021, 14, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeddini, A.; Yeats, A. Amid COVID-19 drug shortages: Proposed plan for reprocessing and reusing salbutamol pressurized metered dose inhalers (pMDIs) for shared use. Drugs Ther. Perspect. 2020, 36, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDA. COVID around the World—Snapshots of the COVID-19 Response as at 9th May 2020. Available online: https://www.the-pda.org/wp-content/uploads/COVID-19-around-the-world-final.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Chalmers, J.D.; Crichton, M.L.; Goeminne, P.C.; Cao, B.; Humbert, M.; Shteinberg, M.; Antoniou, K.M.; Ulrik, C.S.; Parks, H.; Wang, C.; et al. Management of hospitalised adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A European respiratory society living guideline. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2100048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Yue, X.; Wang, J.; Shi, C.; Li, W. Nocturnal oxygen therapy as an option for early COVID-19. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 98, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merks, P.; Jakubowska, M.; Drelich, E.; Świeczkowski, D.; Bogusz, J.; Bilmin, K.; Sola, K.F.; May, A.; Majchrowska, A.; Koziol, M.; et al. The legal extension of the role of pharmacists in light of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruppo di Lavoro Territorio/Ospedale/Università Suggerimenti Operativi e Terapeutici per Pazienti Affetti da COVID-19 Trattati nel Territorio. Available online: https://www.omceovr.it/public/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Suggerimenti-operativi.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- FAMHP. Coronavirus: Measures Taken by the FAMHP and Relevant Partners to Continue to Guarantee Oxygen Supplies. Available online: https://www.famhp.be/en/news/coronavirus_measures_taken_by_the_famhp_and_relevant_partners_to_continue_to_guarantee_oxygen (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Sardesai, I.; Grover, J.; Garg, M.; Nanayakkara, P.B.; Di Somma, S.; Paladino, L.; Anderson, H., III; Gaieski, D.; Galwankar, S.; Stawicki, S. Short term home oxygen therapy COVID-19 patients: The COVID-HOT algorithm. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.; Dawoud, D.M.; Babar, Z.U.D. Drive-thru pharmacy services: A way forward to combat COVID-19 pandemic. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1920–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CNN. Women Are Using Code Words at Pharmacies to Escape Domestic Violence. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/02/europe/domestic-violence-coronavirus-lockdown-intl/index.html?utm_content=2020-04-02T14%3A24%3A06utm_source=twCNNutm_term=linkutm_medium=social (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Ertan, D.; El-Hage, W.; Thierrée, S.; Javelot, H.; Hingray, C. COVID-19: Urgency for distancing from domestic violence. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2020, 11, 1800245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. United Nations UN Supporting ‘Trapped’ Domestic Violence Victims during COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/un-supporting-‘trapped’-domestic-violence-victims-during-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Watson, K.E.; Schindel, T.J.; Barsoum, M.E.; Kung, J.Y. COVID the Catalyst for Evolving Professional Role Identity? A Scoping Review of Global Pharmacists’ Roles and Services as a Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HM. Government Guidance for Pharmacies Implementing the Ask for Ani Domestic Abuse Codeword Scheme #YouAreNotAlone. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/940379/Training_information_-_Ask_for_ANI.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Robinson, J. Thousands of pharmacies participate in domestic abuse codeword scheme. Pharm. J. 2021, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS Pharmacy First Scotland: Information for Patients—gov.scot. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/nhs-pharmacy-first-scotland-information-patients/ (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- ABDA. Bundesvereinigung Deutscher Apothekerverbände Corona-Pandemie: Apotheker als Gefragte Arzneimittelexperten in Impfzentren. Available online: https://www.abda.de/aktuelles-und-presse/pressemitteilungen/detail/corona-pandemie-apotheker-als-gefragte-arzneimittelexperten-in-impfzentren/ (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Tan, S.L.; Zhang, B.K.; Xu, P. Chinese pharmacists’ rapid response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2020, 77, 1096–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa Pinto, G.; Hung, M.; Okoya, F.; Uzman, N. FIP’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Global pharmacy rises to the challenge. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1929–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIP. COVID-19 Information Hub. Available online: https://www.fip.org/coronavirus (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- PGEU. COVID-19 Information Hub. Available online: https://www.pgeu.eu/covid-19-information-hub/ (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Burns, C. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society Managing cold and flu during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pharm. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noemí Rojín Guitián Vacunación COVID: Farmacia y Enfermería Unidas Contra Los Bulos. Available online: https://www.efesalud.com/farmacia-enfermeria-informacion-fiable-vacunacion-covid/ (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Pourroy, B.; Tournamille, J.F.; Bardin, C.; Slimano, F.; Chevrier, R.; Rioufol, C.; Madelaine, I. Providing Oncology Pharmacy Services during the Coronavirus Pandemic: French Society for Oncology Pharmacy (Société Francaise de Pharmacie On-cologique [SFPO]) Guidelines. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2020, 16, e1282–e1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.Q.; Yang, L.; Zhou, P.X.; Li, H.B.; Liu, F.; Zhao, R.S. Recommendations and guidance for providing pharmaceutical care services during COVID-19 pandemic: A China perspective. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1819–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Chan, A.H.Y.; Olaoye, O.; Rutter, V.; Babar, Z.U.D.; Anderson, C.; Anderson, R.; Halai, M.; Matuluko, A.; Nambatya, W.; et al. Needs assessment and impact of COVID-19 on pharmacy professionals in 31 commonwealth countries. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algunmeeyn, A.; El-Dahiyat, F.; Altakhineh, M.M.; Azab, M.; Babar, Z.U.D. Understanding the factors influencing healthcare providers’ burnout during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Jordanian hospitals. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Pharmacists Association. National Survey of Community Pharmacists and Practice Challenges during COVID-19. Available online: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/Infographic_National_Survey_COVID.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Elbeddini, A.; Wen, C.X.; Tayefehchamani, Y.; To, A. Mental health issues impacting pharmacists during COVID-19. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Pharmacists Association. Managing COVID Information Overload Staying Calm in the Storm. Available online: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/SupportPharmacistMentalHealth_EN.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Hess, K.; Bach, A.; Won, K.; Seed, S.M. Community Pharmacists Roles during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 897190020980626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, A. Readiness of community pharmacists to play a supportive and advocacy role in the fight against corona virus disease. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 3121–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visacri, M.B.; Figueiredo, I.V.; de Mendonça Lima, T. Role of pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbeddini, A.; Botross, A.; Gerochi, R.; Gazarin, M.; Elshahawi, A. Pharmacy response to COVID-19: Lessons learnt from Canada. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, E.S.; Philbert, D.; Bouvy, M.L. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the provision of pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 2002–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes.ro. Forbes Romania Facultatea de Farmacie UMF Cluj a Început să Producă Biocide Pentru Spitalele Clujene. Available online: https://www.forbes.ro/facultatea-de-farmacie-umf-cluj-inceput-sa-produca-biocide-pentru-spitalele-clujene-159082 (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Nigro, F.; Tavares, M.; Sato de Souza de Bustamante Monteiro, M.; Toma, H.K.; Faria de Freitas, Z.M.; de Abreu Garófalo, D.; Geraldes Bordalo Montá Alverne, M.A.; Barros dos Passos, M.M.; Pereira dos Santos, E.; Ricci-Júnior, E. Changes in workflow to a University Pharmacy to facilitate compounding and distribution of antiseptics for use against COVID-19. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1997–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallhi, T.H.; Liaqat, A.; Abid, A.; Khan, Y.H.; Alotaibi, N.H.; Alzarea, A.I.; Tanveer, N.; Khan, T.M. Multilevel Engagements of Pharmacists During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Way Forward. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 561924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoro, R.N. COVID-19 pandemic: The role of community pharmacists in chronic kidney disease management supportive care. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1925–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jairoun, A.A.; Al-Hemyari, S.S.; Abdulla, N.M.; El-Dahiyat, F.; Jairoun, M.; AL-Tamimi, S.K.; Babar, Z.U.D. Online medication purchasing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Potential risks to patient safety and the urgent need to develop more rigorous controls for purchasing online medications, a pilot study from the United Arab Emirates. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2021, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, N.; Rasheed, H.; Nayyer, B.; Babar, Z.U.D. Pharmacists at the frontline beating the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, L.; Peterson, G.M.; Naunton, M.; Jackson, S.; Bushell, M. Protecting the Herd: Why Pharmacists Matter in Mass Vaccination. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PTCE. Pharmacy Times Continuing Education COVID-19 Vaccines Curriculum Series Powered by AdvanCE. Available online: https://www.pharmacytimes.org/advance/covid-19-vaccine (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Merks, P.; Religioni, U.; Bilmin, K.; Lewicki, J.; Jakubowska, M.; Waksmundzka-Walczuk, A.; Czerw, A.; Barańska, A.; Bogusz, J.; Plagens-Rotman, K.; et al. Readiness and willingness to provide immunization services after pilot vaccination training: A survey among community pharmacists trained and not trained in immunization during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, S.; Menzel, L.M.; Zieger, M. Google Trends provides a tool to monitor population concerns and information needs during COVID-19 pandemic. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagoto, S.; Waring, M.E.; Xu, R. A call for a public health agenda for social media research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e16661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzy, R.; Abi Jaoude, J.; Kraitem, A.; El Alam, M.B.; Karam, B.; Adib, E.; Zarka, J.; Traboulsi, C.; Akl, E.; Baddour, K. Coronavirus Goes Viral: Quantifying the COVID-19 Misinformation Epidemic on Twitter. Cureus 2020, 12, e7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rovetta, A.; Bhagavathula, A.S. COVID-19-related web search behaviors and infodemic attitudes in Italy: Infodemiological study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwitz, K.K. The pharmacist’s active role in combating COVID-19 medication misinformation. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, e71–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claramunt-García, R.; Muñoz-Cid, C.L.; Sierra-Torres, M.I.; Merino-Almazán, M. Hospital pharmacy in COVID-19. Farm. Hosp. 2020, 44, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goff, D.A.; Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Cairns, K.A.; Eljaaly, K.; Gauthier, T.P.; Langford, B.J.; Mahmoud, S.F.; Messina, A.P.; Michael, U.C.; Saad, T.; et al. Global contributions of pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 3, 1480–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbeddini, A.; Prabaharan, T.; Almasalkhi, S.; Tran, C. Pharmacists and COVID-19. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.B.; Rabbani, S.A. Pharmaceutical care services provided by pharmacists during COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives from around the World. J. Pharm. Health Serv. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Kong, L.; Xu, Q.; Yang, P.; Wang, X.; Chen, N.; Li, L.; Jiang, S.; Lu, X. On-ward participation of clinical pharmacists in a Chinese intensive care unit for patients with COVID-19: A retrospective, observational study. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1853–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.P.; Patel, P.K.; Nori, P. Involving antimicrobial stewardship programs in COVID-19 response efforts: All hands on deck. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 744–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yiaslas, T.A.; Sood, A.; Ono, G.; Rogers-Soeder, T.S.; Kitazono, R.E.; Embree, J.; Spann, C.; Caputo, C.A.; Taylor, J.; Schaefer, S. The Design and Implementation of a Heart Disease Reversal Program in the Veterans Health Administration: Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Fed. Pract. 2020, 37, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Luo, P.; Tang, M.; Hu, Q.; Polidoro, J.P.; Sun, S.; Gong, Z. Providing pharmacy services during the coronavirus pandemic. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 42, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Zheng, S.; Liu, F.; Liu, W.; Zhao, R. Fighting against COVID-19: Innovative strategies for clinical pharmacists. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 17, 1813–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, A.E.; MacDougall, C. Roles of the clinical pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 3, 564–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mcconachie, S.; Martirosov, D.; Wang, B.; Desai, N.; Jarjosa, S.; Hsaiky, L. Surviving the surge: Evaluation of early impact of COVID-19 on inpatient pharmacy services at a community teaching hospital. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2020, 77, 1994–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, K.; Ambreen, G.; Muzammil, M.; Raza, S.S.; Ali, U. Pharmacy services during COVID-19 pandemic: Experience from a tertiary care teaching hospital in Pakistan. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2020, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, A.; Hénaut, L.; Macq, P.Y.; Badoux, L.; Cappe, A.; Porée, T.; Eckes, M.; Dupont, H.; Brazier, M. Rationale for COVID-19 Treatment by Nebulized Interferon-β-1b–Literature Review and Personal Preliminary Experience. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severino, D.; Sconza, I.; Caporlingua, N.; Risoli, A.; Loche, E.; Nigri, N.; Loiacono, S.; Veraldi, M.; Lasala, R.; Rizza, G.; et al. Indicazioni pratiche per la gestione nutrizionale di pazienti affettida SARS-Cov-2: Il ruolo di supporto del farmacista ospedaliero. Bolletino SIFO 2021, 66, 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, M.; Masse, M.; Deldicque, A.; Beuscart, J.B.; De Groote, P.; Desbordes, J.; Fry, S.; Musy, E.; Odou, P.; Puisieux, F.; et al. Analysis of clinical pharmacist interventions in the COVID-19 units of a French university hospital. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E.; Meade, S.; D’Errico, F.; Pavlidis, P.; Luber, R.; Zeki, S.; Hill, K.; Duff, A.; O’Hanlon, D.; Tripoli, S.; et al. The effects of COVID-19 on IBD prescribing and service provision in a UK tertiary centre. GastroHep 2020, 2, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.-A.; Patel, S.; Rayan, D.; Zaharova, S.; Lin, M.; Nafee, T.; Sunkara, B.; Maddula, R.; MacLeod, J.; Doshi, K.; et al. A virtual-hybrid approach to launching a cardio-oncology clinic during a pandemic. Cardio-Oncology 2021, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbeddini, A.; Tayefehchamani, Y.; Yang, L. Strategies to conserve salbutamol pressurized metered-dose inhaler stock levels amid COVID-19 drug shortage. Drugs Ther. Perspect. 2020, 36, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pharmacists’ Role | Pharmaceutical Services |

|---|---|

| Adequate management of drugs, dietary supplements, PPE or sanitizers supplying |

| Stock management efficiency | |

| Limitation of the released quantity of the most requested products | |

| New tasks for pharmacists: delivery of medical oxygen, renewal of prescriptions for chronic diseases, drugs substitution for chronic treatment (including hypnotics, anxiolitics, narcotics or opioid drugs) etc. | |

| Offering of therapeutic alternatives | |

| Manufacturing of antiseptic agents in order to avoid shortages | |

| On-line services (e.g., electronic prescriptions) | |

| Home-delivery | |

| Drive-thru services | |

| COVID-19 patients’ triage (including the differentiation from flu and cold) |

| Detecting specific severe symptoms of COVID-19 | |

| Counselling regarding hygienic rules and the importance of isolation and lock-down | |

| Medication review | |

| Counselling patients reffering to infection control and treatment (e.g., disease, symptoms, medication, ADRs etc.) | |

| Reducing self-medication | |

| Providing written information | |

| Preventing and combating the COVID-19 related stigma, scares, stress etc. | |

| Elaborating the COVID-19 specific documents, therapeutic plans, recommendations or guides |

| Colaboration with medical team (e.g., new drugs, initiating of a new treatment, patient follow-up, clinical studies, antimicrobial stewardship etc.) | |

| Medication review and reconciliation | |

| ADRs, interactions or drug pharmacokinetic monitoring | |

| Staff training regarding PPE usage, reporting of ADRs, manipulation of biological samples or residual materials from patients | |

| Providing information regarding hygiene rules, importance of look-down or isolation |

| Counselling for reducing self-medication or unjustified buying of health products | |

| Elaboration of educational materials: written (e.g., flyers, posters, brochures etc.) and audio-video materials broadcasted on TV, radio or social-media | |

| Counselling in order to avoid COVID-19 related stress, scare or stima | |

| Organization and participation to workshops on COVID-19 topics | |

| Combating the misinformation or unverifiable information |

| Logistic and clinical support to obtain drugs for off-label use in COVID-19 disease | |

| COVID-19 testing | |

| Vaccine administration (including COVID-19 vaccines) | |

| Involvement in “Mask-19” project | |

| Providing free PPEs equipment through Government projects |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghibu, S.; Juncan, A.M.; Rus, L.L.; Frum, A.; Dobrea, C.M.; Chiş, A.A.; Gligor, F.G.; Morgovan, C. The Particularities of Pharmaceutical Care in Improving Public Health Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189776

Ghibu S, Juncan AM, Rus LL, Frum A, Dobrea CM, Chiş AA, Gligor FG, Morgovan C. The Particularities of Pharmaceutical Care in Improving Public Health Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189776

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhibu, Steliana, Anca Maria Juncan, Luca Liviu Rus, Adina Frum, Carmen Maximiliana Dobrea, Adriana Aurelia Chiş, Felicia Gabriela Gligor, and Claudiu Morgovan. 2021. "The Particularities of Pharmaceutical Care in Improving Public Health Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189776

APA StyleGhibu, S., Juncan, A. M., Rus, L. L., Frum, A., Dobrea, C. M., Chiş, A. A., Gligor, F. G., & Morgovan, C. (2021). The Particularities of Pharmaceutical Care in Improving Public Health Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189776