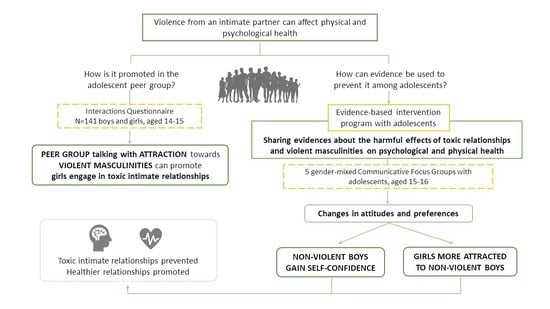

Evidence of Gender Violence Negative Impact on Health as a Lever to Change Adolescents’ Attitudes and Preferences towards Dominant Traditional Masculinities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Collection Instruments

2.2.1. Interactions Questionnaire

2.2.2. Focus Groups

2.2.3. Feedback Questionnaire

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Quantitative Data Analysis

2.3.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Attraction towards Violent Masculinities in the Peer Group Context Can Have an Impact on Promoting That Girls Engage in Toxic Relationships

3.2. When Sharing the Evidence of the Negative Impacts That Toxic Relationships Have on Health with the Group, Transformations in the Peer Group Occurred: Non-Violent Boys Gained Self-Confidence, and Girls Redirected or Reinforced Their Attraction to Non-Violent Boys

3.2.1. Perceived Impact of Known Evidence of the Negative Consequences of Toxic Relationships on Health and the Role of Masculinities

- Researcher:

- And of all the interventions we have made, of the topics we have discussed, which one has impacted you the most?

- Girl 2:

- The one about how toxic relationships affect people, that thing about neurons and those things … I didn’t think it would affect that way, I was freaking out a bit.

- Boy 1:

- Yes, I thought it affected psychologically, not your health.

- Girl 1:

- It impacted us a lot because we were not aware of this knowledge.

- Girl 2:

- Sure, they don’t tell you, if you have a toxic relationship, besides from the fact that someone can hit you and hurt you physically, they can also do it psychologically and health-wise. So… we didn’t know about that. I think that, for everyone, has been the one that has had the most impact. (FG school 1)

- Girl 1:

- The one of good boy and bad boy [session about types of masculinity] … because you know what will happen, the consequences. The session about toxic relationships also because you know that if you get sick you get depressed and everything. And in terms of health, it is your health, and you can die too, so … (FG school 2)

3.2.2. Non-Violent Boys Gain Self-Confidence in the Peer Group

- Boy 2:

- Well, I’ve been told more than once, “hey, hook up with this person”, just because, and I say: “hey, I don’t know that person, I’ve known her shortly and she is not the type of person I like”, and they said: “no, do it, that way you look cool”, and I say: “Well, no, I don’t want to look cool, I want to look like someone normal, I don’t want to look cool either saying ‘I hooked up with this girl just because’, because for me that’s not being cool. Because I have had acquaintances who say “I have hooked up so many times or I have fucked so many times”, and I say: “look, that won’t make you better than me”. And well, I always tell them this argument because I say: “even if you do this more than others, you will not be better than someone else, you may be even worse.” I always say this statement and they say: “OK, I understand you”, and I say: “OK, then don’t repeat it, because if that happened to you, I wouldn’t tell you.” And with that argument and a little more talking with them, they already understand it, but then there are others who go on and on and on … and I say “nope” “why?” “Because I say so and that’s it.”

- Researcher:

- And how has the project helped you on this issue?

- Boy 2:

- To become aware of what I really want and not what others want for me.

- Researcher:

- And besides from becoming aware, how has it helped you to respond to these situations?

- Boy 2:

- Being honest and dismissing the opinion of others, not being at that level of today’s society, that the more flings you have and the more hook ups you have, the better person you are and way cooler, well no. The fact of practically not wanting to be like that average who says to prefer that, and well, mainly, that. (FG school 1)

3.2.3. Girls Redirect Their Attraction to Non-Violent Boys

- Girl 1:

- Let’s see, it is true that the bad guy is the one who attracts the most and all that, but then after these talks you realize: “feeling attracted to that person doesn’t give me anything” and then you go looking for the good things of other people and you say: “I am more attracted to the one who is not bad than the bad one.” (FG school 1)

- Girl 2:

- With the interventions, we have realized how bad others [“violent boys”] are because …

- Girl 3:

- … you appreciate the others [“non-violent boys”] more. (FG school 3)

- Researcher:

- What relationships do you dream of? What is your ideal partner like? What about your ideal relationship? (…)

- Girl 1:

- The cool guy, no, that’s it, that’s more than clear. The typical bad boy no, because we don’t want a toxic person.

- Girl 2:

- Well, someone who is a good person, kind …

- Girl 1:

- And also egalitarian … respectful (…)

- Researcher:

- Do you think that the intervention has helped you change that idea or that dream of …

- Girl 1:

- Yes (…) maybe girls like the bad boy I don’t know why but … looking at it in another way, you stop liking him because of all the things you’ve seen and what can happen, then it’s like different and it changes your way of thinking and seeing that person (FG school 2)

- Girl 1:

- Yes (…) that helps us to know what we want too and if there is a person who is not for us, then we already have an idea of how to get away or how … or situations of how to say no, perhaps. (FG school 2)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Öhman, A.; Burman, M.; Carbin, M.; Edin, K. The public health turn on violence against women: Analysing Swedish healthcare law, public health and gender-equality policies. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564793. (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- World Health Organization; on behalf of the United Nations Inter-Agency Working Group on Violence Against Women Es-timation and Data. Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018. Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence Against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence Against Women; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256. (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos, G.P. Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2009, 5, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougea, A.; Anagnostouli, M.; Angelopoulou, E.; Spanou, I.; Chrousos, G. Psychosocial and Trauma-Related Stress and Risk of Dementia: A Meta-Analytic Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2020, 0891988720973759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, B.; Granger, D.A. Gender-based violence and trauma in marginalized populations of women: Role of biological embedding and toxic stress. Health Care Women Int. 2018, 39, 1038–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuyuki, K.; Cimino, A.N.; Holliday, C.N.; Campbell, J.C.; Al-Alusi, N.A.; Stockman, J.K. physiological changes from vio-lence-induced stress and trauma enhance hiv susceptibility among women. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019, 16, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joos, C.M.; McDonald, A.; Wadsworth, M. Extending the toxic stress model into adolescence: Profiles of cortisol reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 107, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boen, C.E.; Kozlowski, K.; Tyson, K.D. “Toxic” schools? How school exposures during adolescence influence trajectories of health through young adulthood. SSM-Popul. Health 2020, 11, 100623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Igualdad. Macroencuesta de Violencia Contra la Mujer 2019; Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género; Gobierno de España, 2019. Available online: https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/violenciaEnCifras/macroencuesta2015/pdf/Macroencuesta_2019_estudio_investigacion.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Fletcher, J. The effects of intimate partner violence on health in young adulthood in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racionero-Plaza, S.; León, J.A.P.; Iglesias, M.M.; Ugalde, L. Toxic nightlife relationships, substance abuse, and mental health: Is there a link? A qualitative case study of two patients. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 608219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, W.A.; Welsh, D.P.; Furman, W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, L.F.; Meyer-Bahlburg, H.F. African-American and Latina inner-city girls’ reports of romantic and sexual de-velopment. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2003, 20, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schad, M.M.; Szwedo, D.E.; Antonishak, J.; Hare, A.; Allen, J.P. The broader context of relational aggression in adolescent ro-mantic relationships: Predictions from peer pressure and links to psychosocial functioning. J. Youth Adolesc. 2008, 37, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gonzalez-Mendez, R.; Aguilera, L.; Ramírez-Santana, G. Weighing Risk Factors for Adolescent Victimization in the Context of Romantic Relationship Initiation. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 36, NP8395–NP8413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, L.R.; Martínez, I.; Flecha, A.; Álvarez-Cifuentes, P. Successful communicative focus groups with teenagers and young people: How to identify the mirage of upward mobility. Qual. Inq. 2014, 20, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Palomar, J.; Capllonch, M.; Aiello, E. Analyzing Male Attractiveness models from a communicative approach: Social-ization, attraction, and gender-based violence. Qual. Inq. 2014, 20, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guarinos, V.; Martín, I.S.-L. Masculinity and rape in Spanish cinema: Representation and collective imaginary. Masculinities Soc. Chang. 2021, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J. Radical Love: A Revolution for the 21st Century; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.; Gwyther, K.; Swann, R.; Casey, K.; Featherston, R.; Oliffe, J.L.; Englar-Carlson, M.; Rice, S.M. Operationalizing positive masculinity: A theoretical synthesis and school-based framework to engage boys and young men. Health Promot. Int. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner-Cortens, D.; Wright, A.; Hurlock, D.; Carter, R.; Krause, P.; Crooks, C. Preventing adolescent dating violence: An outcomes protocol for evaluating a gender-transformative healthy relationships promotion program. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2019, 16, 100484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha, R.; Puigvert, L.; Rios, O. The new alternative masculinities and the overcoming of gender violence. international and multidisciplinary. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 2, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls-Carol, R.; Madrid-Pérez, A.; Merrill, B.; Legorburo-Torres, G. “Come on! He has never cooked in his life!” New alternative masculinities putting everything in its place. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 674675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Eugenio, L.; del Cerro, A.T.; Crowther, J.; Merodio, G. Making choices in discourse: New alternative masculinities opposing the “Warrior’s Rest. ” Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 674054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Mello, R.; Bonell-García, L.; Castro-Sandúa, M.; Oliver-Pérez, E. Three steps above heaven? Really? That’s all tactic! New alternative masculinities dismantling dominant traditional masculinity’s strategies. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 673829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-González, O.; Ramis-Salas, M.; Peña-Axt, J.; Racionero-Plaza, S. Alternative Friendships to Improve Men’s Health Status. The Impact of the New Alternative Masculinities’ Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racionero-Plaza, S.; Ugalde, L.; Merodio, G.; Fernández, N.G. “Architects of Their Own Brain.” Social Impact of an Intervention Study for the Prevention of Gender-Based Violence in Adolescence. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Eugenio, L.; Puigvert, L.; Ríos, O.; Cisneros, R.M. Communicative Daily Life Stories: Raising Awareness About the Link Between Desire and Violence. Qual. Inq. 2020, 26, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jansson, P.M.; Kullberg, C. An Explorative Study of Men’s Masculinity Constructions and Proximity to Violence against Women. Masculinities Soc. Chang. 2020, 9, 284–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Eugenio, L.; Racionero-Plaza, S.; Duque, E.; Puigvert, L. Female university students’ preferences for different types of sexual relationships: Implications for gender-based violence prevention programs and policies. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Impact of the evidence of the negative consequences of toxic relationships and the role of masculinities | This category includes adolescents’ explanations of the perceived impact that the intervention sessions on health and masculinities had on them compared to the other interventions. |

| 2. Consequences on boys: non-violent boys gain self-confidence in the peer group | This category includes boys’ explanations of the intervention program’s consequences (particularly sessions on health and masculinities) had on them. |

| 3. Consequences on girls: girls redirected their attraction to non-violent boys | This category includes girls’ explanations of the intervention program’s consequences (particularly sessions on health and masculinities) had on them. |

| 28. Has a Girl in Your Group of Friends at the High School Ever Started a Relationship Because of What Her Friends Told Her? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28. (a) Yes | 28. (b) No | ||||

| N 4 | % | N | % | ||

| 20. How do your group of friends at the high school speak about non-egalitarian boys, “bad boys”? [DTM] (select a maximum of 5 options) | Group talk showing acceptance and attraction 1 | 187 | 66% | 98 | 63% |

| Group talk showing rejection and unattraction 2 | 46 | 16% | 41 | 26% | |

| Other responses 3 | 51 | 18% | 17 | 11% | |

| Total responses | 284 | 100% | 156 | 100% | |

| 22. How do your group of friends at the high school speak about egalitarian boys who are not self-confident? [OTM] (select a maximum of 5 options) | Group talk showing acceptance and attraction | 111 | 44% | 93 | 54% |

| Group talk showing rejection and unattraction | 107 | 42% | 54 | 31% | |

| Other responses | 36 | 14% | 26 | 15% | |

| Total responses | 254 | 100% | 173 | 100% | |

| 24. How do your group of friends at the high school speak about egalitarian and self-confident boys? [NAM] (select a maximum of 5 options) | Group talk showing acceptance and attraction | 199 | 76% | 151 | 78% |

| Group talk showing rejection and unattraction | 24 | 9% | 11 | 6% | |

| Other responses | 39 | 16% | 31 | 16% | |

| Total responses | 262 | 100% | 193 | 100% | |

| 25. Girls Feel Attracted to Boys with Attitudes of Disrespect towards Them [Mirage of Upward Mobility]. Do You Know Any Situation of This Kind? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25. (a) Yes | 25. (b) No | ||||

| N 4 | % | N | % | ||

| 20. How do your group of friends at the high school speak about non-egalitarian boys, “bad boys”? [DTM] (select a maximum of 5 options) | Group talk showing acceptance and attraction 1 | 210 | 67% | 71 | 55% |

| Group talk showing rejection and unattraction 2 | 48 | 15% | 39 | 30% | |

| Other responses 3 | 54 | 17% | 18 | 14% | |

| Total responses | 312 | 100% | 128 | 100% | |

| 22. How do your group of friends at the high school speak about egalitarian boys who are not self-confident? [OTM] (select a maximum of 5 options) | Group talk showing acceptance and attraction | 115 | 41% | 88 | 58% |

| Group talk showing rejection and unattraction | 120 | 43% | 38 | 25% | |

| Other responses | 44 | 16% | 26 | 17% | |

| Total responses | 279 | 100% | 152 | 100% | |

| 24. How do your group of friends at the high school speak about egalitarian and self-confident boys? [NAM] (select a maximum of 5 options) | Group talk showing acceptance and attraction | 182 | 69% | 142 | 73% |

| Group talk showing rejection and unattraction | 35 | 13% | 22 | 11% | |

| Other responses | 47 | 18% | 31 | 16% | |

| Total responses | 264 | 100% | 195 | 100% | |

| Intervention | Average Score 1 |

|---|---|

| Intervention 1 | 3.09 |

| Intervention 2 | 2.47 |

| Intervention 3 | 3.06 |

| Intervention 4 | 3.30 |

| Intervention 5 | 3.31 |

| Intervention 6 | 3.04 |

| Intervention 7 | 2.93 |

| All interventions | 3.06 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Padrós Cuxart, M.; Molina Roldán, S.; Gismero, E.; Tellado, I. Evidence of Gender Violence Negative Impact on Health as a Lever to Change Adolescents’ Attitudes and Preferences towards Dominant Traditional Masculinities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189610

Padrós Cuxart M, Molina Roldán S, Gismero E, Tellado I. Evidence of Gender Violence Negative Impact on Health as a Lever to Change Adolescents’ Attitudes and Preferences towards Dominant Traditional Masculinities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189610

Chicago/Turabian StylePadrós Cuxart, Maria, Silvia Molina Roldán, Elena Gismero, and Itxaso Tellado. 2021. "Evidence of Gender Violence Negative Impact on Health as a Lever to Change Adolescents’ Attitudes and Preferences towards Dominant Traditional Masculinities" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189610

APA StylePadrós Cuxart, M., Molina Roldán, S., Gismero, E., & Tellado, I. (2021). Evidence of Gender Violence Negative Impact on Health as a Lever to Change Adolescents’ Attitudes and Preferences towards Dominant Traditional Masculinities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189610