Ethnic Stereotype Formation and Its Impact on Sojourner Adaptation: A Case of “Belt and Road” Chinese Migrant Workers in Montenegro

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Cultural Adaptation among Sojourners

1.2. Ethnic Stereotype Formation Is the Missing Link in Cultural Adaptation

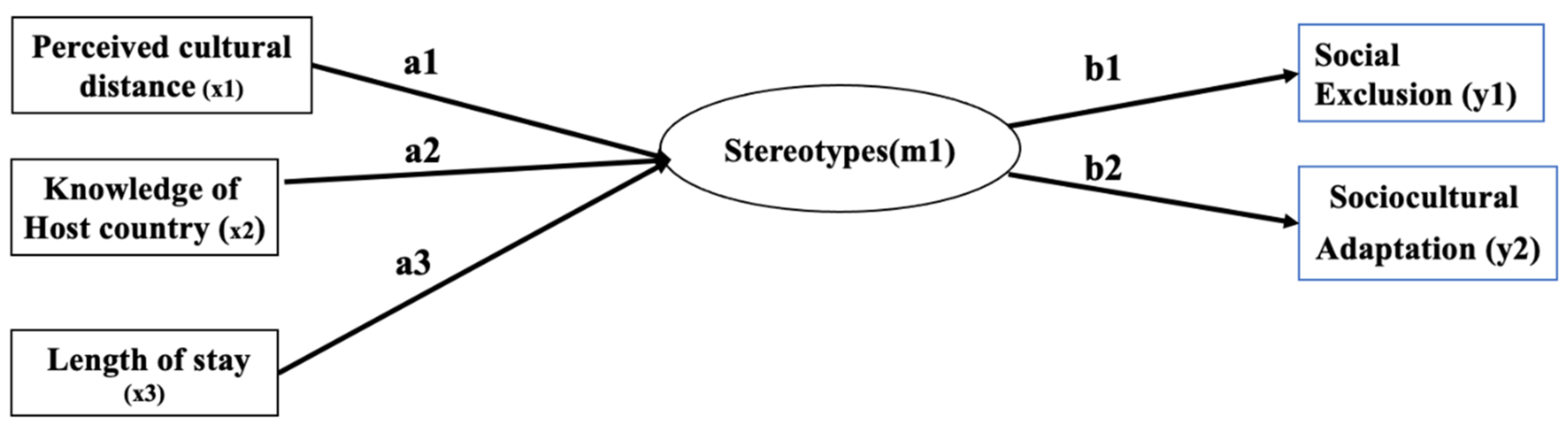

1.3. The Present Research

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Analytical Procedure and Power Analysis

2.3. Measurement

3. Results

3.1. Test of Hypotheses 1—Correlations

3.2. Test of Hypotheses 2—Direct Effects

3.3. Test of Hypotheses 3—Indirect Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. Prior Knowledge Is Needed in Establishing Ethnic Stereotypes

4.2. Contributions and Implications

5. Limitations and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2005, 29, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. How shall we all work together?Achieving diversity and equity in work settings. Organ. Dyn. 2021, 50, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Bochner, S.; Furnham, A. The Psychology of Culture Shock; Routledge: Hove, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sam, D.L.; Berry, J.W. The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, A.; Vauclair, C.M. Stereotype accommodation: A socio-cognitive perspective on migrants’ cultural adaptation. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2018, 49, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demes, K.A.; Geeraert, N. Measures matter: Scales for adaptation, cultural distance, and acculturation orientation revisited. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A.; English, A.S.; Zhijia, Z.; Jose, P.; Ward, C.; Jianhong, M. Is the utility of secondary coping a function of ethnicity or the context of reception? A longitudinal study across Western and eastern cultures. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2017, 48, 1230–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudmin, F. Constructs, measurements and models of acculturation and acculturative stress. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2009, 33, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leersnyder, J.; Mesquita, B.; Kim, H.S. Where do my emotions belong? A study of immigrants’ emotional acculturation. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güngör, D.; Bornstein, M.H.; De Leersnyder, J.; Cote, L.; Ceulemans, E.; Mesquita, B. Acculturation of personality: A three-culture study of Japanese, Japanese Americans, and European Americans. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2013, 44, 701–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safdar, S.; Berno, T. Sojourners. In The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology, 2nd ed.; Sam, D.L., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhawuk, D.P. Intercultural training for the global workplace: Review 2021, synthesis, and theoretical explorations. In Handbook of Culture, Organization, and Work; Bhagat, R.S., Steers, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 462–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J.S. Ethic identity and acculturation. In Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and Applied Research; Chun, K.M., Balls Organista, P., Marín, G., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horenczyk, G.; Jasinskaja-Lahti, I.; Sam, D.L.; Vedder, P. Mutuality in acculturation: Towards an integration. Z. Psychol. 2013, 221, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, R.; Chasiotis, A.; Bender, M.; Van de Vijver, F.J. Collective identity and well-being of Bulgarian Roma adolescents and their mothers. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, A.J.; Fiske, S.T.; Glick, P. The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.L.; Fiske, S.T. Not an outgroup, not yet an ingroup: Immigrants in the stereotype content model. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2006, 30, 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, P.G. Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, A. Stereotype accommodation concerning older people. Int. J. Psychol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanciu, A.; Vauclair, C.M.; Rodda, N. Evidence for stereotype accommodation as an expression of immigrants’ socio-cognitive adaptation. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2019, 72, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, R.J.; Turner, R.N. Cognitive adaptation to the experience of social and cultural diversity. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triandis, H.C.; Vassiliou, V. Frequency of contact and stereotyping. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1967, 7, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lönnqvist, J.E.; Jasinskaja-Lahti, I.; Verkasalo, M. Rebound effect in personal values: Ingrian Finnish migrants’ values two years after migration. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2013, 44, 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeraert, N.; Demoulin, S. Acculturative stress or resilience? A longitudinal multilevel analysis of sojourners’ stress and self-esteem. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2013, 44, 1241–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiker, I.E.; Cox, J.L.; Miller, P.M. The measurement of cultural distance and its relationship to medical consultations, symptomatology and examination performance of overseas students at Edinburgh University. Soc. Psychiatry 1980, 15, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demes, K.A.; Geeraert, N. The highs and lows of a cultural transition: A longitudinal analysis of sojourner stress and adaptation across 50 countries. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Galchenko, I.; Van de Vijver, F.J. The role of perceived cultural distance in the acculturation of exchange students in Russia. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2007, 31, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suanet, I.; Van de Vijver, F.J. Perceived cultural distance and acculturation among exchange students in Russia. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 19, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeraert, N.; Demoulin, S.; Demes, K.A. Choose your (international) contacts wisely: A multilevel analysis on the impact of intergroup contact while living abroad. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2013, 38, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashima, E.S.; Abu-Rayya, H.M. Longitudinal associations of cultural distance with psychological well-being among Australian immigrants from 49 countries. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, A.S.; Zeng, Z.J.; Ma, J.H. The stress of studying in China: Primary and secondary coping interaction effects. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanciu, A. Four sub-dimension of stereotype content: Explanatory evidence from Romania. Int. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 19, 14–20. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8097/eb710c2b4efb5dc583db6e53907581a14080.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Cavalli-Sforza, L.L.; Feldman, M.W. Cultural Transmission and Evolution: A Quantitative Approach; No. 16.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Braly, K. Racial stereotypes of one hundred college students. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1933, 28, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnke, K.; Arnaut, C.; Bremer, T.; Chinyemba, R.; Kiewitt, Y.; Koudadjey, A.K.; Neubert, L. Toward emically informed cross-cultural comparisons: A suggestion. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 1655–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T.F.; Tropp, L.R.; Wagner, U.; Christ, O. Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2011, 35, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckmüller, S.; Abele, A.E. The density of the big two. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 44, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.H. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1990, 25, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, T.D. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Madon, S.; Guyll, M.; Aboufadel, K.; Montiel, E.; Smith, A.; Palumbo, P.; Jussim, L. Ethnic and national stereotypes: The Princeton trilogy revisited and revised. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Des Rosiers, S.; Huang, S.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Unger, J.B.; Knight, G.P.; Szapocznik, J. Developmental trajectories of acculturation in Hispanic adolescents: Associations with family functioning and adolescent risk behavior. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 1355–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searle, W.; Ward, C. The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1990, 14, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Zagefka, H. The dynamics of acculturation: An intergroup perspective. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 44, 129–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, S.; Dixon, J. The “contact hypothesis”: Critical reflections and future directions. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2017, 11, e12295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mähönen, T.A.; Jasinskaja-Lahti, I. Acculturation expectations and experiences as predictors of ethnic migrants’ psychological well-being. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2013, 44, 786–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, H.; Huang, X.; Ding, Y. Simulated home: An effective cross-cultural adjustment model for Chinese expatriates. Empl. Relat. 2020, 42, 1017–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Lin, E.-Y. There are homes at the four corners of the seas: Acculturation and adaptation of overseas Chinese. In Oxford Handbook of Chinese Psychology; Bond, M.H., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigler, R.S.; Liben, L.S. A developmental intergroup theory of social stereotypes and prejudice. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 2006, 34, 39–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Tezanos-Pinto, P.; Bratt, C.; Brown, R. What will the others think? In-group norms as a mediator of the effects of intergroup contact. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 49, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, A.S.; Geeraert, N. Crossing the rice-wheat border: Not all intra-cultural adaptation is equal. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, A.S.; Worlton, D.S. Coping with uprooting stress during domestic educational migration in China. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2017, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulich, S.J.; Zhang, R. The multiple frames of ‘Chinese’ values: From tradition to modernity and beyond. In The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Psychology; Bond, M.H., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 241–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.P.; Kulich, S.J. Communicating across cultures with people from China. In The Sage Encyclopedia of Intercultural Communication Competence; Bennett, J., Ed.; Sage Reference: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 67–73. Available online: https://sk.sagepub.com/reference/the-sage-encyclopedia-of-intercultural-competence/i1328.xml (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Crandall, C.S.; Eshleman, A. A justification-suppression model of the expression and experience of prejudice. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 414–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, U.; Christ, O.; Pettigrew, T.F.; Stellmacher, J.; Wolf, C. Prejudice and minority proportion: Contact instead of threat effects. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2006, 69, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.N.; Hewstone, M.; Voci, A. Reducing explicit and implicit outgroup prejudice via direct and extended contact: The mediating role of self-disclosure and intergroup anxiety. Interpers. Relat. Group Process. 2007, 93, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrer, J. ‘New Shanghailanders’ or ‘New Shanghainese’: Western expatriates’ narratives of emplacement in Shanghai. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2010, 36, 1211–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpara, J.O.; Kabongo, J.D. Cross-cultural training and expatriate adjustment: A study of western expatriates in Nigeria. J. World Bus. 2011, 46, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Jackson, M.H. Global relocation: An examination of the corporate influence on expatriate adjustment. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2015, 53, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stereotype Content | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive traits | |||

| 1 | 友好/友善 (Friendly) | 82 | 47.1 |

| 2 | 热心肠/热情 (Warm-hearted) | 63 | 36.2 |

| 3 | 有礼貌 (Polite) | 36 | 20.7 |

| 4 | 漂亮 (Beautiful) | 26 | 14.9 |

| 5 | 生活悠闲/惬意/休闲 (Relaxed) | 21 | 12.1 |

| 6 | 好客 (Hospitable) | 20 | 11.5 |

| 7 | 微笑 (Smiling) | 16 | 9.2 |

| 8 | 注重生活/懂生活/享受生活 (Enjoying life) | 16 | 9.2 |

| 9 | 善良/和蔼/亲切 (Kind) | 15 | 8.6 |

| 10 | 乐观 (Optimistic) | 14 | 8.0 |

| Negative traits | |||

| 1 | 懒/懒散/懒惰 (Lazy) | 37 | 21.3 |

| 2 | 固执/倔强 (Stubborn) | 13 | 7.5 |

| 3 | 穷 (Poor) | 11 | 6.3 |

| 4 | 迟到/不守时 (Unpunctual) | 7 | 4.0 |

| 5 | 不守信用 (Dishonest) | 6 | 3.4 |

| 6 | 不灵活/一根筋/轴 (Inflexible) | 5 | 2.9 |

| 7 | 吹牛 (Boastful) | 5 | 2.9 |

| 8 | 自大 (Arrogant) | 4 | 2.3 |

| 9 | 不友好 (Unfriendly) | 3 | 1.7 |

| 10 | 自我 (Egoistic) | 3 | 1.7 |

| Variable | α | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Positive stereotype | ~ | 3.12 | 1.46 | - | 0.70 *** | −0.23 ** | 0.20 ** | −0.15 * | −0.29 *** | 0.22 ** | −0.11 |

| 2 | Negative stereotype | ~ | −0.90 | 1.21 | - | −0.32 *** | 0.08 | −0.22 ** | −0.26 *** | 0.23 ** | −0.11 | |

| 3 | PCD | 0.88 | 4.88 | 0.91 | - | −0.24 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.03 | −0.20 ** | 0.03 | ||

| 4 | Knowledge of host country | 0.88 | 3.08 | 0.86 | - | 0.17 * | −0.08 | 0.24 ** | 0.02 | |||

| 5 | Length of stay | ~ | 18.94 | 0.66 | - | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| 6 | Social Exclusion | 0.81 | 2.28 | 0.98 | - | −0.42 *** | 0.03 | |||||

| 7 | SCA | 0.91 | 4.70 | 0.92 | - | −0.07 | ||||||

| 8 | Age | ~ | 29.07 | 6.19 | - |

| Social Exclusion Y1 | Sociocultural Adaptation Y2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Latent Stereotype Model | Indirect effect | Indirect effect |

| Knowledge of host country (×1) | −0.098 * [−0.261, −0.006] | 0.110 * [0.000, 0.302] |

| Perceived cultural distance (×2) | 0.082 * [0.010, 0.247] | −0.092 * [−0.272, −0.001] |

| Length of stay in host country (×3) | 0.072 ** [0.022, 0.192] | −0.081 * [−0.191, −0.005] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

English, A.S.; Zhang, X.; Stanciu, A.; Kulich, S.J.; Zhao, F.; Bojovic, M. Ethnic Stereotype Formation and Its Impact on Sojourner Adaptation: A Case of “Belt and Road” Chinese Migrant Workers in Montenegro. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9540. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189540

English AS, Zhang X, Stanciu A, Kulich SJ, Zhao F, Bojovic M. Ethnic Stereotype Formation and Its Impact on Sojourner Adaptation: A Case of “Belt and Road” Chinese Migrant Workers in Montenegro. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9540. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189540

Chicago/Turabian StyleEnglish, Alexander S., Xinyi Zhang, Adrian Stanciu, Steve J. Kulich, Fuxia Zhao, and Milica Bojovic. 2021. "Ethnic Stereotype Formation and Its Impact on Sojourner Adaptation: A Case of “Belt and Road” Chinese Migrant Workers in Montenegro" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9540. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189540

APA StyleEnglish, A. S., Zhang, X., Stanciu, A., Kulich, S. J., Zhao, F., & Bojovic, M. (2021). Ethnic Stereotype Formation and Its Impact on Sojourner Adaptation: A Case of “Belt and Road” Chinese Migrant Workers in Montenegro. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9540. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189540