Promotion of Mental Health Literacy in Adolescents: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What are the programmes/interventions for promoting MHL among adolescents in school settings?

- What are the characteristics of the programmes/interventions for promoting MHL among adolescents highlighted in the literature?

- In what settings/contexts are these programmes/interventions carried out?

- What are the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of these programmes/interventions?

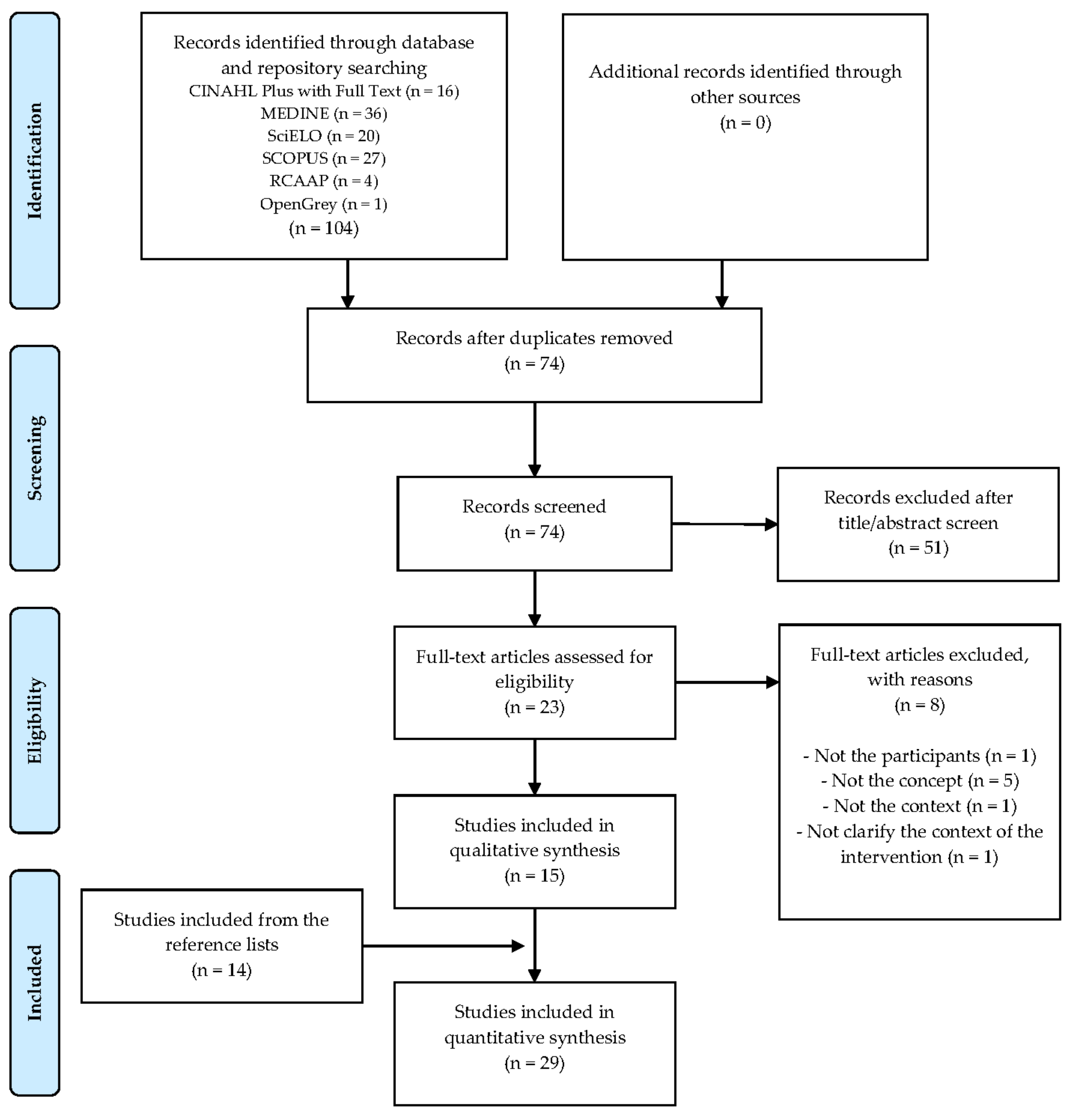

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Participants—articles targeting adolescents aged between 10 and 19 years, without diagnosed mental illness;

- Concept—studies on programmes/interventions for promoting MHL, covering at least one of the components of MHL;

- Context—we accepted studies that included adolescents in a school setting (2nd and 3rd cycles of basic education and secondary education, which corresponds to 5–12th grade), including online intervention and/or face to face intervention.

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection of the Studies

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Component—Knowledge on Achieving/Maintaining Good Mental Health

3.2. Component—Knowledge about Mental Disorders and Their Treatments

3.3. Component—Reducing Stigma Associated with Mental Disorders

3.4. Component—Help-Seeking

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Scoping Review Details | |

|---|---|

| Title | |

| Aim(s) | |

| Research Questions | |

| Inclusion Criteria | |

| Population | |

| Concept | |

| Context | |

| Study designs | |

| Study and Program/Intervention Details | |

| Detailed study quote (author/s, date, title, journal, volume, number, pages) | |

| Country | |

| Aim(s) of the study | |

| Type of study | |

| Programme/intervention name | |

| Aim(s) of the programme/intervention | |

| Participants of the programe/intervention | |

| Implementation setting | |

| Duration and frequency of the programme/intervention | |

| Description of the programme/intervention | |

| Assessment tools | |

| Main outcomes | |

| Barriers and Facilitators | |

| References List | |

| Other studies of interest for the review indicated in the study reference list | |

References

- Biddle, L.; Donovan, J.; Sharp, D.; Gunnell, D. Explaining non-help-seeking amongst young adults with mental distress: A dynamic interpretive model of illness behaviour. Sociol. Health Illn. 2007, 29, 983–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Medina, M. Abrir Espaço à Saúde Mental—Estudo Piloto Sobre Conhecimentos, Estigma e Necessidades Relativas a Quaetões de Saúde Mental, Junto de Alunos do 9° Ano de Escolaridade (Dissertação de Mestrado não Publicada). Master’s Thesis, Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Porto, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pedreiro, A. Literacia em Saúde Mental de Adolescentes e Jovens Sobre Depressão e Abuso de Álcool. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, J.; Tay, Y.; Klainin-Yobas, P. Mental health literacy levels. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, M.; Baptista, H.; Mendes, J.M.; Magalhães, P.; Caldas-de-Almeida, J.M. Implementing the World Mental Health Survey Initiative in Portugal-rationale, design and fieldwork procedures. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2013, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kieling, C.; Baker-Henningham, H.; Belfer, M.; Conti, G.; Ertem, I.; Omigbodun, O.; Rohde, L.A.; Srinath, S.; Ulkuer, N.; Rahman, A. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. Lancet 2011, 378, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Mental Health: Mapping Actions of Nongovernmental Organizations and Other International Development Organizations; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; McGrath, P.J.; Hayden, J.; Kutcher, S. Mental health literacy measures evaluating knowledge, attitudes and help-seeking: A scoping review. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rosa, A.; Loureiro, L.; Sequeira, C. Literacia em saúde mental sobre abuso de álcool em adolescentes: Desenvolvimento de um instrumento de medida. Rev. Port. Enferm. Saúde Ment. 2016, 16, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waldmann, T.; Staiger, T.; Oexle, N.; Rüsch, N. Mental health literacy and help-seeking among unemployed people with mental health problems. J. Ment. Health 2019, 29, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, L.M.d.J.; de Freitas, P.M.F.P. Effectiveness of the mental health first aid program in undergraduate nursing students. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2020, 5, e19078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F.; Korten, A.E.; Jacomb, P.A.; Christensen, H.; Rodgers, B.; Pollitt, P. “Mental health literacy”: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med. J. Aust. 1997, 166, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y.; Coniglio, C. Mental health literacy: Past, present, and future. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y.; Costa, S.; Gusmão, R.; Skokauskas, N.; Sourander, A. Enhancing mental health literacy in young people. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 25, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The WHO World Health Report 2001: New Understanding—New Hope; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rickwood, D.; Thomas, K. Conceptual measurement framework for help-seeking for mental health problems. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2012, 5, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Livingston, J.D.; Tugwell, A.; Korf-Uzan, K.; Cianfrone, M.; Coniglio, C. Evaluation of a campaign to improve awareness and attitudes of young people towards mental health issues. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, L.; Dias, P.; Palha, F. Finding Space to Mental Health—Promoting mental health in adolescents: Pilot study. Educ. Health 2014, 32, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Morgado, T.; Botelho, M.R. Intervenções promotoras da literacia em saúde mental dos adolescentes: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Rev. Port. Enferm. Saúde Ment. 2014, 1, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peterson, J.; Pearce, P.F.; Ferguson, L.A.; Langford, C.A. Understanding scoping reviews: Definition, purpose, and process. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse. Pract. 2017, 29, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Baldini Soares, C.; Khalil, H.; Parker, D. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Hayden, J.A.; Kutcher, S.; Zygmunt, A.; McGrath, P. The effectiveness of school mental health literacy programs to address knowledge, attitudes and help seeking among youth. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2013, 7, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nobre, J.; Sequeira, C.; Ferré-Grau, C. Promotion of Mental Health Literacy in Adolescents: A Scoping Review Protocol. Cent. Open Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Casañas, R.; Arfuch, V.-M.; Castellví, P.; Gil, J.-J.; Torres, M.; Pujol, A.; Castells, G.; Teixidó, M.; San-Emeterio, M.T.; Sampietro, H.M.; et al. “EspaiJove.net”—A school-based intervention programme to promote mental health and eradicate stigma in the adolescent population: Study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milin, R.; Kutcher, S.; Lewis, S.P.; Walker, S.; Wei, Y.; Ferrill, N.; Armstrong, M.A. Impact of a Mental Health Curriculum on Knowledge and Stigma among High School Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bella-Awusah, T.; Adedokun, B.; Dogra, N.; Omigbodun, O. The impact of a mental health teaching programme on rural and urban secondary school students’ perceptions of mental illness in southwest Nigeria. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2014, 26, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skre, I.; Friborg, O.; Breivik, C.; Johnsen, L.I.; Arnesen, Y.; Wang, C.E.A. A school intervention for mental health literacy in adolescents: Effects of a non-randomized cluster controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kutcher, S.; Bagnell, A.; Wei, Y. Mental Health Literacy in Secondary Schools. A Canadian Approach. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2015, 24, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C.; Erse, M.P.; Simões, R.; Façanha, J.; Marques, L. + Contigo na promoção da saúde mental e prevenção de comportamentos suicidários em meio escolar. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2013, 3, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcluckie, A.; Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y.; Weaver, C. Sustained improvements in students’ mental health literacy with use of a mental health curriculum in Canadian schools. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y.; Morgan, C. Successful application of a Canadian mental health curriculum resource by usual classroom teachers in significantly and sustainably improving student mental health literacy. Can. J. Psychiatry 2015, 60, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lubman, D.I.; Berridge, B.J.; Blee, F.; Jorm, A.F.; Wilson, C.J.; Allen, N.B.; McKay-Brown, L.; Proimos, J.; Cheetham, A.; Wolfe, R. A school-based health promotion programme to increase help-seeking for substance use and mental health problems: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2016, 17, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eschenbeck, H.; Lehner, L.; Hofmann, H.; Bauer, S.; Becker, K.; Diestelkamp, S.; Kaess, M.; Moessner, M.; Rummel-Kluge, C.; Salize, H.-J.; et al. School-based mental health promotion in children and adolescents with StresSOS using online or face-to-face interventions: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial within the ProHEAD Consortium. Trials 2019, 20, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, Y.; Petrie, K.; Buckley, H.; Cavanagh, L.; Clarke, D.; Winslade, M.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Manicavasagar, V.; Christensen, H. Effects of a classroom-based educational resource on adolescent mental health literacy: A cluster randomized controlled trial. J. Adolesc. 2014, 37, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, L.; Dias, P.; Duarte, A.; Veiga, E.; Dias, C.C.; Palha, F. Is it possible to “Find space for mental health” in young people? Effectiveness of a school-based mental health literacy promotion program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hart, L.M.; Morgan, A.J.; Rossetto, A.; Kelly, C.M.; Mackinnon, A.; Jorm, A.F. Helping adolescents to better support their peers with a mental health problem: A cluster-randomised crossover trial of teen Mental Health First Aid. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2018, 52, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Swartz, K.; Musci, R.J.; Beaudry, M.B.; Heley, K.; Miller, L.; Alfes, C.; Townsend, L.; Thornicroft, G.; Wilcox, H.C. School-based curriculum to improve depression literacy among US secondary school students: A randomized effectiveness trial. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, 1970–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, E.A.; Aseltine, R.H.; James, A. The SOS suicide prevention program: Further evidence of efficacy and effectiveness. Prev. Sci. 2016, 17, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, K.; Patterson, P.; Torgerson, C.; Turner, E.; Jenkinson, D.; Birchwood, M. Impact of contact on adolescents’ mental health literacy and stigma: The schoolspace cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindow, J.C.; Hughes, J.L.; South, C.; Minhajuddin, A.; Gutierrez, L.; Bannister, E.; Trivedi, M.H.; Byerly, M.J. The Youth Aware of Mental Health Intervention: Impact on Help Seeking, Mental Health Knowledge, and Stigma in U.S. Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, C.L.M.; Leung, W.W.T.; Wong, A.K.H.; Loong, K.Y.; Kok, J.; Hwang, A.; Lee, E.H.M.; Chan, S.K.W.; Chang, W.C.; Chen, E.Y.H. Destigmatizing psychosis: Investigating the effectiveness of a school-based programme in Hong Kong secondary school students. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2019, 13, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, L.M.; Mason, R.J.; Kelly, C.M.; Cvetkovski, S.; Jorm, A.F. ‘teen Mental Health First Aid’: A description of the program and an initial evaluation. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2016, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ojio, Y.; Foo, J.C.; Usami, S.; Fuyama, T.; Ashikawa, M.; Ohnuma, K.; Oshima, N.; Ando, S.; Togo, F.; Sasaki, T. Effects of a school teacher-led 45-minute educational program for mental health literacy in pre-teens. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2018, 13, 984–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojio, Y.; Yonehara, H.; Taneichi, S.; Yamasaki, S.; Ando, S.; Togo, F.; Nishida, A.; Sasaki, T. Effects of school-based mental health literacy education for secondary school students to be delivered by school teachers: A preliminary study. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 69, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojio, Y.; Mori, R.; Matsumoto, K.; Nemoto, T.; Sumiyoshi, T.; Fujita, H.; Morimoto, T.; Nishizono-Maher, A.; Fuji, C.; Mizuno, M. Innovative approach to adolescent mental health in Japan: School-based education about mental health literacy. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2020, 15, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, J.P. Effectiveness of Universal School-Based Mental Health Awareness Programs Among Youth in the United States: A Systematic Review. J. Sch. Health 2016, 86, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Moleiro, C. Resultados de um programa piloto de desestigmatização da saúde mental juvenil. Rev. Port. Saúde Pública 2016, 34, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gonçalves, M.; Moleiro, C.; Cook, B. The Use of a Video to Reduce Mental Health Stigma Among Adolescents. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 5, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lopez Cervera, R.; Tye, S.J.; Ekker, S.C.; Pierret, C. Adolescent mental health education InSciEd Out: A case study of an alternative middle school population. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Zambrano, F.; García-Morales, E.; García-Franco, M.; Miguel, J.; Villellas, R.; Pascual, G.; Arenas, O.; Ochoa, S. Intervention for reducing stigma: Assessing the influence of gender and knowledge. World J. Psychiatr. 2013, 3, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellor, C. School-based interventions targeting stigma of mental illness: Systematic review. Psychiatr. Bull. 2014, 38, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolan, P.H.; Gorman-Smith, D.; Henry, D.; Schoeny, M. The benefits of booster interventions: Evidence from a family-focused prevention program. Prev. Sci. 2009, 10, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Search | CINAHL Plus with Full Text | Medline | SciELO | Scopus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1: adolescent * | 139,077 | 2,112,677 | 18,767 | 2,304,095 |

| S2: “mental health” | 145,021 | 279,261 | 10,078 | 331,070 |

| S3: literacy | 21,227 | 23,359 | 2542 | 88,214 |

| S4: “health literacy” | 7534 | 10,829 | 478 | 15,027 |

| S5: “mental health literacy” | 511 | 776 | 48 | 1146 |

| S6: program * | 511,350 | 1,398,162 | 65,511 | 3,505,488 |

| S7: course * | 122,063 | 616,864 | 19,770 | 1,511,044 |

| S8: intervention * | 458,783 | 1,024,234 | 32,994 | 1,467,357 |

| S9: promotion | 102,071 | 184,606 | 10,507 | 296,991 |

| S10: school | 173,702 | 4,315,891 | 32,732 | 1,182,107 |

| S11: (S3 OR S4 OR S5) | 21,227 | 23,359 | 2542 | 88,214 |

| S12: (S6 OR S7 OR S8) | 971,745 | 2,791,998 | 106,869 | 6,065,802 |

| S13: (S1 AND S2 AND S11 AND S12 AND S9 AND S10) | 18 | 42 | 34 | 34 |

| With time limiter 2013–2020 | 16 | 36 | 20 | 27 |

| Search | RCAAP | OpenGrey |

|---|---|---|

| S1: adolescent * | 13,879 | 4001 |

| S2: “mental health” | 3081 | 1948 |

| S3: school | 13,587 | 23,518 |

| S4: (S1 AND S2 AND S3) | 4 | 17 |

| With time limiter 2013–2020 | 4 | 1 |

| Author (s), Year | Country | Component: Knowledge Good MH | Component: Knowledge MH Disorders | Component: Stigma | Component: Help Seeking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lubman et al. (2016) [40] | Australia | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Yang et al. (2018) [57] | USA | ✓ | |||

| Campos et al. (2014) [22] | Portugal | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Eschenbeck et al. (2019) [41] | Germany | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Bella-Awusah et al. (2014) [34] | Nigeria | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Lindow et al. (2020) [48] | USA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Hui et al. (2019) [49] | China | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Perry et al. (2014) [42] | Australia | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Casañas et al. (2018) [32] | Spain | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ojio et al. (2020) [53] | Japan | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Kutcher, Bagnell & Wei (2015) [36] | Canada | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Mcluckie et al. (2014) [38] | Canada | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Gonçalves et al. (2016) [55] | Portugal | ✓ | |||

| Santos et al. (2013) [37] | Portugal | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Campos et al. (2018) [43] | Portugal | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Mellor (2014) [59] | UK | ✓ | |||

| Hart et al. (2016) [50] | Australia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Hart et al. (2018) [44] | Australia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Swartz et al. (2017) [45] | USA | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Schilling et al. (2016) [46] | USA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Kutcher, Wei & Morgan (2015) [39] | Canada | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Milin et al. (2016) [33] | Canada | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Chisholm et al. (2016) [47] | UK | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Ojio et al. (2018) [51] | Japan | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Ojio et al. (2015) [52] | Japan | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Skre et al. (2013) [35] | Norway | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Gonçalves et al. (2015) [56] | Portugal | ✓ | |||

| Salerno (2016) [54] | USA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Martínez-Zambrano et al. (2013) [58] | Spain | ✓ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nobre, J.; Oliveira, A.P.; Monteiro, F.; Sequeira, C.; Ferré-Grau, C. Promotion of Mental Health Literacy in Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189500

Nobre J, Oliveira AP, Monteiro F, Sequeira C, Ferré-Grau C. Promotion of Mental Health Literacy in Adolescents: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189500

Chicago/Turabian StyleNobre, Joana, Ana Paula Oliveira, Francisco Monteiro, Carlos Sequeira, and Carme Ferré-Grau. 2021. "Promotion of Mental Health Literacy in Adolescents: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189500

APA StyleNobre, J., Oliveira, A. P., Monteiro, F., Sequeira, C., & Ferré-Grau, C. (2021). Promotion of Mental Health Literacy in Adolescents: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9500. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189500