Using Community Based Research Frameworks to Develop and Implement a Church-Based Program to Prevent Diabetes and Its Complications for Samoan Communities in South Western Sydney

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR)

2. Materials and Methods

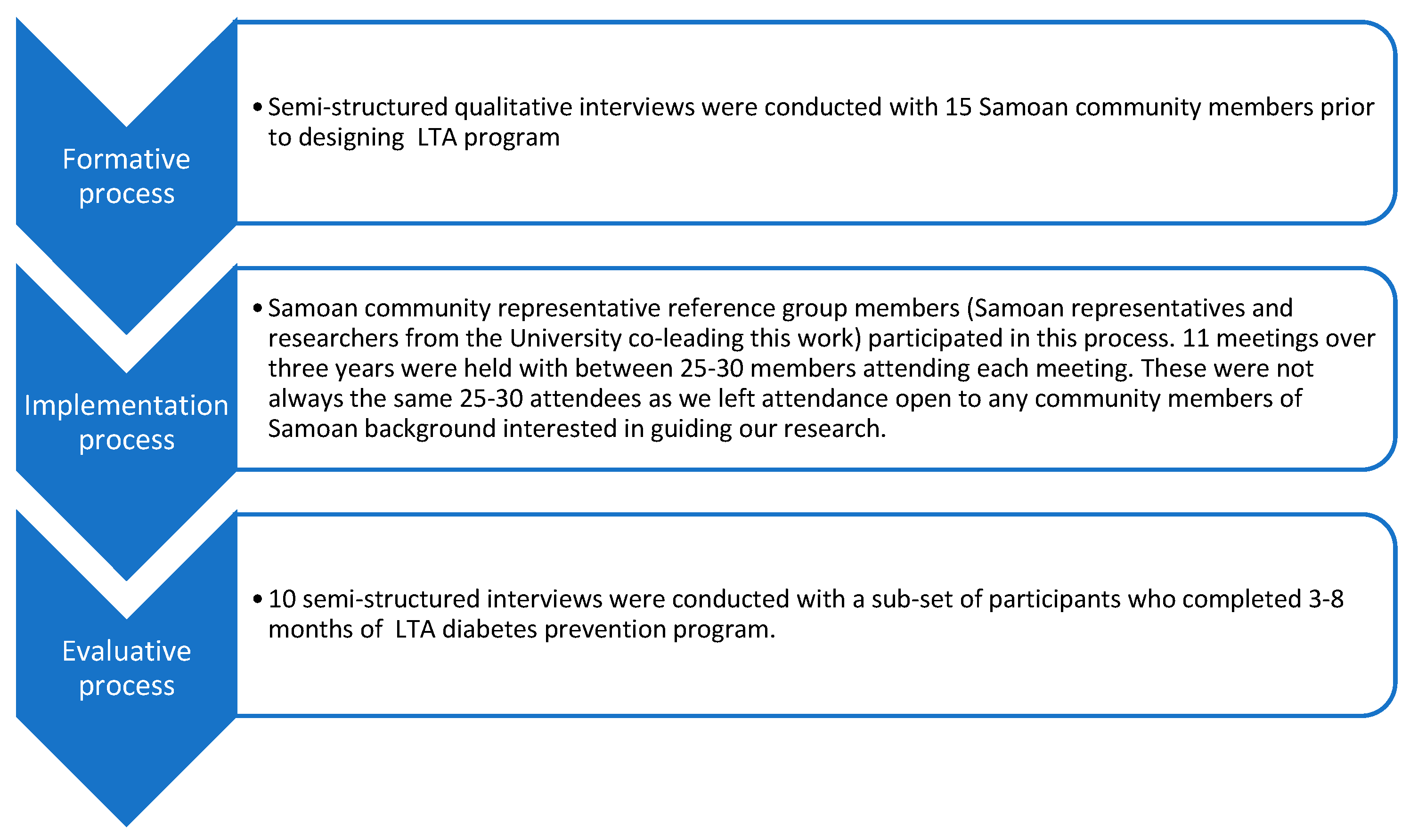

2.1. Formative Interviews

2.2. Implementation Process Data

2.3. Evaluative Interviews

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

“I think to help our young people because they have more understanding, they have the language now, they are more into the, the normal community now, …but I’m sure helps with the attitude of parents at home”. P112

“…. if it was down to like pastors and ministers of churches because I think they play a huge role especially when you have a congregation of 200 people and whatever the minister says everyone does hey! So it would be good to have them on board coz they have huge influence”. P107

“…. because our people, especially the old age, they can’t understand because you know, because there are some other medical words they cannot understanding but we if we are having, bringing in those people, those people, they can talk in the language, might be the message of delivering, they’re going to get the message”. P111

“The use of PSFs was a great idea and great value. These are people from a cultural perspective and leaders are held in high esteem”. P117

“We need good leaders because I think often times Samoans are good followers…. so if we are able to find good leaders that are able to lead our people to good dieting and you know, introducing good food and be able to lead them by way of healthy cooking and things like that I think we can overcome”. P104

“I look at it as most of the, each individual families, kind of having one person they are affected with diabetes. You can see most of the children they are getting obesity and they are having diabetes at a young age. It’s very sad. It’s very sad”. P111

“…. visuals are very good, you’ve got to make it interesting you know, all that. I love the chart…... I understood all that”. P102

“For us, it’s a very good program and even our food from now on with my family, ….my wife just buy a packet of salad, green salad, just put it in the fridge and the bread, make a sandwich and cheese, that’s our lunch, with my family and my sons. This worked like that. We changed the red meat, more salad, sugar. We’re not drinking anymore fizzy drink….” P119

“When I volunteered, I was worried about language barrier but the messages from our coaches (community activators) were easy to understand. I could deliver the messages of the intervention in Samoa”. P121

“…. it’s better to go to the people and let our people facilitate those, those who can share the information and deliver in a way that they feel that we are all part of it. We’re not there to teach them, just to go there and raise awareness and the effect of so many people die young because of diabetes”. P112

“Perhaps even having like posters of our own people, you know, like pushing it out that way, and then just maybe having like a number for our people to call you know, for information that’s available to them”. P101

“The University has also benefit from the contribution of the Samoan Community. We have shared our Samoan culture, beliefs, traditions and understandings—and you have ensured culturally appropriate processes and developed an intervention that has been language clear and culturally acceptable. While maintaining the importance of a healthy lifestyle change. This has been well received by our community”. P121

“The other thing is of course, for Samoans, it’s very difficult to share what problems you have. You can easily say I’m a diabetic, but they won’t tell you whether they are suffering from the usual associated you know, problems with diabetes, and so by holding in that information, people are not getting the right diagnosis”. P105

“I think the fact that people are less active and our food, and it’s rude to say no. So, and proportions are big, I think doesn’t help……even though they try and bring exercise programs into the church and encourage, it’s still, it’s very revolved around food and you can see the bottles of soft drinks on the table…”. P103

“Perhaps make data collection to be more efficient as it dips into schedules of participants. Data collection was performed on activity nights, which was to the annoyance of multiple church members who only wished to enjoy the activities”. P122

“The intervention is good. I was given a letter by LTA because my sugar was high. It was the first time I see a doctor in a long time. I went to see my doctor and said I have diabetes and confirmed I have diabetes”. P124

“Samoan people are not reading people. They traditionally pass information down orally and visually. We should look at having simplified (resources) and have someone speak in a video…”. P117

“We have made changes to the Sabbath community meal. We used to enjoy large meal and have plenty of food. But with LTA we have learnt new techniques and started eating lighter meals. We have agreed to this and now eat outside to enjoy each other. PSFs are leading our own Zumba classes, weight friendly classes”. P121

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Batley, J. What Does the 2016 Census Reveal about Pacific Islands Communities in Australia? 2017. Available online: https://devpolicy.org/2016-census-reveal-about-pacific-islands-communities-in-australia-20170928/ (accessed on 3 November 2020).

- Ravulo, J.J. Pacific Communities in Australia. 2015. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4901&context=sspapers (accessed on 3 November 2020).

- Colagiuri, R.; Thomas, M.; Buckley, A. Preventing Type 2 Diabetes in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities in NSW. 2007. Available online: https://www.saxinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Preventing-type-2-diabetes-in-culturally-and-linguistically-diverse-communities-in-NSW.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Wong, V. Gestational diabetes mellitus in five ethnic groups: A comparison of their clinical characteristics. Diabet. Med. 2012, 29, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Naseri, T.; Linhart, C.; Morrell, S.; Taylor, R.; McGarvey, S.T.; Magliano, D.J.; Zimmet, P. Trends in diabetes and obesity in Samoa over 35 years, 1978–2013. Diabet. Med. 2017, 34, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.A.; Lock, L.J.; Archer, L.E.; Ahmed, Z. Awareness of Gestational Diabetes and its Risk Factors among Pregnant Women in Samoa. Hawaii J. Med. Public Health 2017, 76, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ndwiga, D.W.; McBride, K.A.; Simmons, D.; Macmillan, F. Diabetes, its risk factors and readiness to change lifestyle behaviours among Australian Samoans living in Sydney: Baseline data for church. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2019, 31, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, K.C.; Ware, R.; Felise Tautalasoo, L.; Stanley, R.; Scanlan-Savelio, L.; Schubert, L. Dietary habits of Samoan adults in an urban Australian setting: A cross-sectional study. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Queensland Health. Queensland Health Response to Pacific Islander and Māori Health Needs Assessment; Division of the Chief Health Officer, Queensland Health: Brisbane, Australia, 2011. Available online: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0037/385867/qh-response-data.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Simmons, D.; Fleming, C.; Voyle, J.; Fou, F.; Feo, S.; Gatland, B. A pilot urban church-based programme to reduce risk factors for diabetes among Western Samoans in New Zealand. Diabet Med. 1998, 15, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, N.L.; Johnson, W.; Hart, C.N.; Triche, E.W.; Ah Ching, J.; Muasau-Howard, B.; McGarvey, S.T. Gestational weight gain among American Samoan women and its impact on delivery and infant outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hawley, N.L.; McGarvey, S.T. Obesity and Diabetes in Pacific Islanders: The Current Burden and the Need for Urgent Action. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichiho, H.M.; Roby, F.T.; Ponausuia, E.S.; Aitaoto, N. An Assessment of Non-Communicable Diseases, Diabetes, and Related Risk Factors in the Territory of American Samoa: A Systems Perspective. Hawaii J. Med. Public 2013, 72, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Samoa Profile. 2018. Available online: http://www.healthdata.org/Samoa (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Åberg, K.; Dai, F.; Sun, G.; Keighley, E.D.; Indugula, S.R.; Bausserman, L.; Viali, S.; Tuitle, J.; Deka, R.; Weeks, D.E.; et al. A genome-wide linkage scan identifies multiple chromosomal regions influencing serum lipid levels in the population on the Samoan islands. J. Lipid Res. 2008, 49, 2169–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hawley, N.L.; Minster, R.L.; Weeks, D.E.; Viali, S.; Reupena, M.S.; Sun, G.; Cheng, H.; Deka, R.; McGarvey, S.T. Prevalence of adiposity and associated cardiometabolic risk factors in the samoan genome-wide association study. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2014, 26, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ndwiga, D.W.; Macmillan, F.; McBride, K.A.; Simmons, D. Lifestyle Interventions for People with, and at Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Polynesian Communities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Israel, B.; Eng, E.; Schulz, A.; Parker, E.A. Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research for Health; Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, A.; Shaban, R.; Stone, C. Fa’afaletui: A framework for the promotion of renal health in an Australian Samoan community. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2011, 22, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McElfish, P.A.; Kohler, P.; Smith, C. Community-driven research agenda to reduce health disparities. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2015, 8, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McElfish, P.A.; Narcisse, M.; Long, C.R.; Ayers, B.L.; Hawley, N.L.; Aitaoto, N.; Riklon, S.; Su, L.J.; Ima, S.Z.; Wilmoth, R.O.; et al. Leveraging community-based participatory research capacity to recruit Pacific Islanders into a genetics study. J. Community Genet. 2017, 8, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Minkler, M.; Wallerstein, N. Community-Based Participatory Research: From Process to Outcomes, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, R.; Simmons, D.; Bourke, L.; Muir, J. Development of guidelines for non-Indigenous people undertaking research among the Indigenous population of north-east Victoria. Med. J. Aust. 2002, 176, 482–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElfish, P.A.; Bridges, M.D.; Hudson, J.S.; Purvis, R.S.; Bursac, Z.; Kohler, P.O.; Goulden, P.A. Family Model of Diabetes Education with a Pacific Islander Community. Diabetes. Educ. 2015, 41, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tobias, J.; Richmond, C.; Luginaah, I. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) with indigenous communities: Producing respectful and reciprocal research. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2013, 8, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyle, J.A.; Simmons, D. Community development through partnership: Promoting health in an urban indigenous community in New Zealand. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 49, 1035–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, R.S.; Bing, W.I.; Jacob, C.J.; Lang, S.; Mamis, S.; Ritok, M.; Rubon-Chutaro, J.; McElfish, P.A. Community Health Warriors: Marshallese Community Health Workers’ Perceptions and Experiences with CBPR and Community Engagement. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2017, 11, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B. Review of Community-Based Research: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berge, J.; Tai, M.; Doherty, W. Using community-based participatory research to target health disparities. Fam. Relat. 2009, 58, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbie-Smith, G.; Adimora, A.; Youmans, S.; Muhammad, M.; Blumenthal, C.; Ellison, A.; Akers, A.; Council, B.; Thigpen, Y.; Wynn, M.; et al. Project GRACE: A Staged Approach to Development of a Community–Academic Partnership to Address HIV in Rural African American Communities. Health Promot. Pract. 2011, 12, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simmons, D.; Rush, E.; Crook, N. Development and piloting of a community health worker-based intervention for the prevention of diabetes among New Zealand Maori in Te Wai o Rona: Diabetes Prevention Strategy. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 1318–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simmons, D.; Voyle, J.A.; Fou, F.; Feo, S.; Leakehe, L. Tale of two churches: Differential impact of a church-based diabetes control programme among Pacific Islands people in New Zealand. Diabet. Med. 2004, 21, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndwiga, D.W.; Macmillan, F.; McBride, K.A.; Thompson, R.; Reath, J.; Alofivae-Doorbinia, O.; Abbott, P.; McCafferty, C.; Aghajani, M.; Rush, E.; et al. Outcomes of a church-based lifestyle intervention among Australian Samoan in Sydney—Le Taeao Afua diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 160, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Y.; Alofivae-Doorbinnia, O.; Reath, J.; MacMillan, F.; Simmons, D.; McBride, K.; Abbott, P. Samoan migrants’ perspectives on diabetes: A qualitative study. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2019, 30, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D. Quirkos; Version 2.0; Quirkos Limited: Edinburgh, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, A.; Thomson, S.B. Framework Analysis: A Qualitative Methodology for Applied Policy Research. J. Adm. Gov. 2009, 4, 72–79. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2760705 (accessed on 3 September 2021).

- Hubbell, F.A.; Luce, P.H.; McMullin, J.M. Exploring beliefs about cancer among American Samoans: Focus group findings. Cancer Detec. Prev. 2005, 29, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitaoto, N.; Braun, K.L.; Dang, K.L.; So‘a, T. Cultural Considerations in Developing Church-Based Programs to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities Among Samoans. Ethn. Health 2007, 12, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickert, N.W. Re-Examining Respect for Human Research Participants. Kennedy Inst. Ethics J. 2009, 19, 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzer, J.K.; Ellis, L.; Merritt, M.W. Why we need community engagement in medical research. J. Investig. Med. 2014, 62, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Levine, H. Some reflections on Samoan cultural practice and group identity in contemporary Wellington, New Zealand. J. Intercult. 2003, 24, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janes, C.; Pawson, I. Migration and biocultural adaption: Samoans in California. Soc. Sci. Med. 1986, 22, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehar, M.; Duignan, P.; Casswell, S. Formative evaluation of a health promotion programme: Heartbeat New Zealand. In Psychology and Social Change; Thomas, D.R., Veno, A., Eds.; The Dunmore Press: Palmerston North, New Zealand, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Storms, L.; Wallace, S.P. Use of mammography screening among older Samoan women in Los Angeles county: A diffusion network approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depue, J.; Dunsiger, S.; Seiden, A.D.; Blume, J.; Rosen, R.K.; Goldstein, M.G.; Nu’usolia, O.; Tuitele, J.; McGarvey, S.T. Nurse-community health worker team improves diabetes care in American Samoa: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1947–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| CBPR Principles by Israel et al., 2013 Applied in the Research Partnership | CBPR Approaches Utilized from Previous Learnings from Henderson et al., 2002; Voyle & Simmons, 1999. |

|---|---|

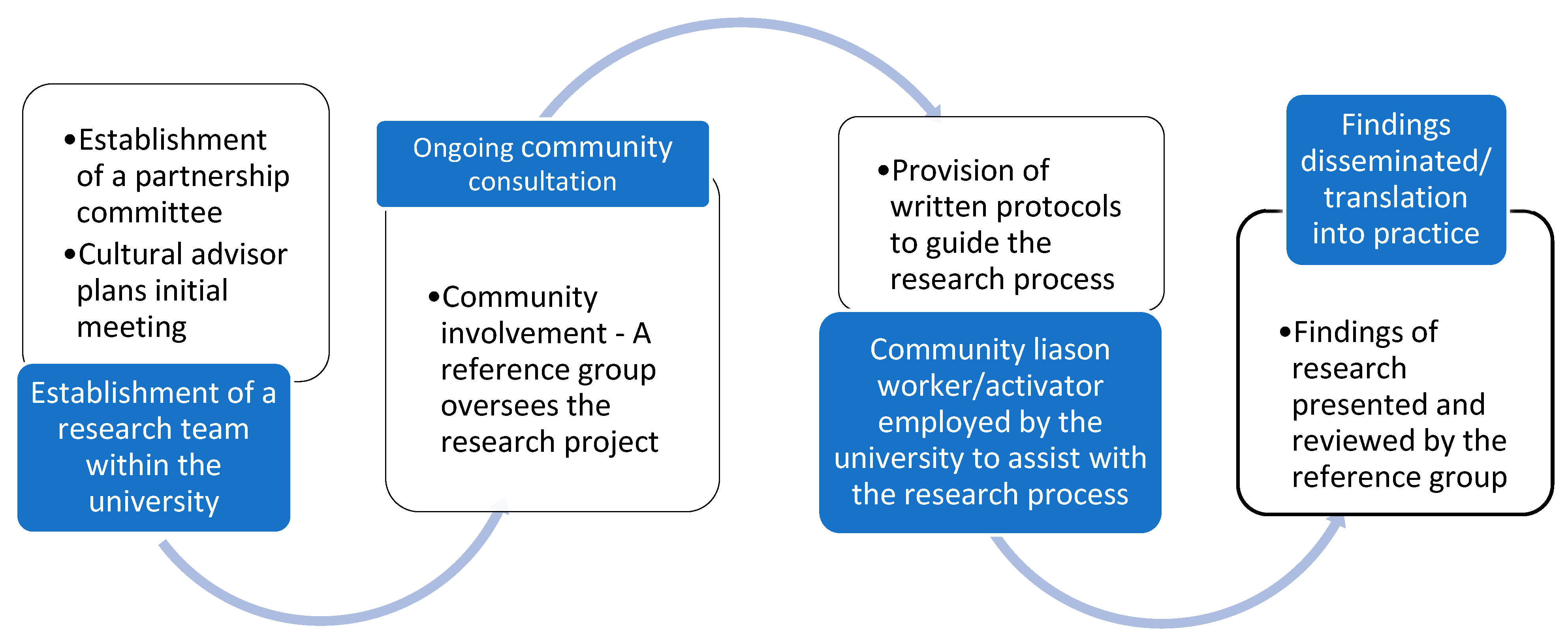

| 1. CBPR acknowledges community as a unit of identity. Le Taeao Afua recognised and included key members of community such as church pastors and community elders, as equal partners throughout the research process. | 1. Establishment of a partnership committee to identify health priorities and develop specific projects with the help of a cultural advisor. The cultural advisor plans initial meetings with community members and University researchers. A Samoan GP aware of previous work conducted by researchers at the University with Samoan communities in New Zealand, approached these researchers due to her concerns of the high prevalence of diabetes in her community. The Samoan GP, a leader within the Samoan community in Sydney, arranged for an initial meeting between key community representatives and the University researchers. A community reference group was initiated following this meeting. |

| 2. CBPR builds on strengths and resources within the community. Le Taeao Afua identified community assets and resources and built on the strengths within the community, such as established local churches and individual skills (PSFs). | 2. Establishment of a research team within the University to carry out tasks set by the partnership committee. To ensure the recommendations from the community members/community reference group were implemented, a research team comprising of researchers from the University and Samoan community activators (once recruited into the project) was initiated. |

| 3. CBPR facilitates a collaborative, equitable partnership in all phases of research, involving an empowering and power-sharing process that attends to social inequalities. A partnership between the Samoan community and university partners was developed. To ensure a community-engaged research a Samoan community reference group was initiated to oversee the research process. The reference group consisted of Samoan leaders/community members and researchers from the university. | 3. Provision of written protocols (Memorandum of Understanding (MoU)) to guide the research process. The MoU should be developed in consultation with the community. The MoU is intended to guide both parties in the research process and develop trust for ongoing relationships by ensuring that roles and responsibilities are defined. A MoU was developed in collaboration with the Samoan community reference group and the University and was signed by each participating church and the University before the start of the intervention. |

| 4. CBPR fosters co-learning and capacity building among all partners. Le Taeao Afua acknowledged that both partners (Samoan community and researchers) had diverse skills and expertise. Community members were trained to deliver the intervention promoting community capacity within the Samoan community and researchers received research training where necessary and updated their cultural competence skills. | 4. Community consultation—The community must be consulted about any research project being proposed to be conducted within it. Approval to undertake the project must be sought from community gate keepers. A representative from the local community should be nominated to monitor the implementation of the MoU. Permission and approval to undertake the diabetes research program was sought from the key Samoan community leaders during and following the initial meeting organised by the Samoan GP. The community should be notified of the financial costs of conducting the research process Community representatives attending the reference group were notified of funding applications to undertake the project and the costs of developing, delivering and evaluating the program. In-kind contributions were also described so that the community were aware of what the research team and research partner organizations were providing to support the program. |

| 5. CBPR integrates and achieves a balance between knowledge generation and intervention for the mutual benefit of all partners. Le Taeoa Afua gathered information from community members prior to conducting the intervention and incorporated the community knowledge in planning and delivery of the intervention. Le Taeoa Afua built community capacity by training and involving volunteer peer supporters to deliver the intervention. The program also ensured a balance between community benefits with addressing the research aim and objectives. For example, participants were required to notify the CAs if they were involved in other lifestyle interventions rather than excluding them from the research. | 5. Community involvement—A reference group should be initiated to oversee the research project. Roles of the reference group should be made with respect to specific cultural and social needs. Regular reference group meetings should be held to ensure the committee is up to date with the research process, obstacles, issues and to give feedback. A Samoan community reference group comprising of 25–30 members was initiated following a meeting with key community representatives. Meetings were held every 3–5 months. The reference group co-chairs decided who to send invitations to from within their communities. New members were welcomed through invitation from the reference group members. |

| 6. CBPR emphasises local relevance of public health problems and on ecological perspectives that attend the multiple determinants of health. Le Taeoa Afua addressed a local health problem identified by the Samoan community. To ensure that the research was successful, Le Taeao Afua discussed both barriers and facilitators to a healthy lifestyle in the community, with the aim of developing strategies to overcome these barriers during the research process and promote better outcomes by empowering community. | 6. A community liaison worker/activator should be employed by the university to assist with consultation, data collection and analysis. The reference committee should be involved in the recruitment process of a cultural person who represents the community at the university. For community and individual empowerment peer volunteers should be trained and utilized in the research process. The community reference group oversaw the recruitment and employment of two bilingual Samoan community activators (fluent in English and Samoan) by the University to deliver the intervention. |

| 7. CBPR involves systems development using a cyclical and iterative process. Findings from Le Taeoa Afua were used to develop a larger study with the aim of reducing the impact of diabetes and its complications in the wider Pasifika communities in Sydney. | 7. Data storage and retention—The research project should be conducted in accordance with data principles and agreed protocols with the community. Individual privacy and confidentiality should be maintained, and the community should not have access to individual data. Research data was stored on password protected university computers and databases. Individual data were available to participants on their request. Individual data was not shared with anyone else. Publication of research data and reports from Le Taeao Afua were approved by designated community representatives. All publications arising from Le Taeao Afua included details of the joint research process between the Samoan community and research team at the university. Research findings were disseminated at community reference group meetings. |

| 8. CBPR disseminates results to all partners and involves them in the wider dissemination of results. Findings of Le Taeao Afua were disseminated to all members of the community reference group and community members. Individual data were available on request to all participants and overall study findings were available to reference group members to distribute to their respective audiences. | |

| 9. CBPR involves a long-term process and commitment to sustainability. Le Taeao Afua was designed to ensure that the intervention was sustainable and able to address multiple determinants of health. Following the initial pilot study focusing on diabetes, other health initiatives have been introduced to meet the needs of the community. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ndwiga, D.W.; McBride, K.A.; Simmons, D.; Thompson, R.; Reath, J.; Abbott, P.; Alofivae-Doorbinia, O.; Patu, P.; Vaovasa, A.T.; MacMillan, F. Using Community Based Research Frameworks to Develop and Implement a Church-Based Program to Prevent Diabetes and Its Complications for Samoan Communities in South Western Sydney. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179385

Ndwiga DW, McBride KA, Simmons D, Thompson R, Reath J, Abbott P, Alofivae-Doorbinia O, Patu P, Vaovasa AT, MacMillan F. Using Community Based Research Frameworks to Develop and Implement a Church-Based Program to Prevent Diabetes and Its Complications for Samoan Communities in South Western Sydney. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(17):9385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179385

Chicago/Turabian StyleNdwiga, Dorothy W., Kate A. McBride, David Simmons, Ronda Thompson, Jennifer Reath, Penelope Abbott, Olataga Alofivae-Doorbinia, Paniani Patu, Annalise T. Vaovasa, and Freya MacMillan. 2021. "Using Community Based Research Frameworks to Develop and Implement a Church-Based Program to Prevent Diabetes and Its Complications for Samoan Communities in South Western Sydney" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 17: 9385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179385

APA StyleNdwiga, D. W., McBride, K. A., Simmons, D., Thompson, R., Reath, J., Abbott, P., Alofivae-Doorbinia, O., Patu, P., Vaovasa, A. T., & MacMillan, F. (2021). Using Community Based Research Frameworks to Develop and Implement a Church-Based Program to Prevent Diabetes and Its Complications for Samoan Communities in South Western Sydney. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 9385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179385