Developing the Healthy and Competitive Organization in the Sports Environment: Focused on the Relationships between Organizational Justice, Empowerment and Job Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

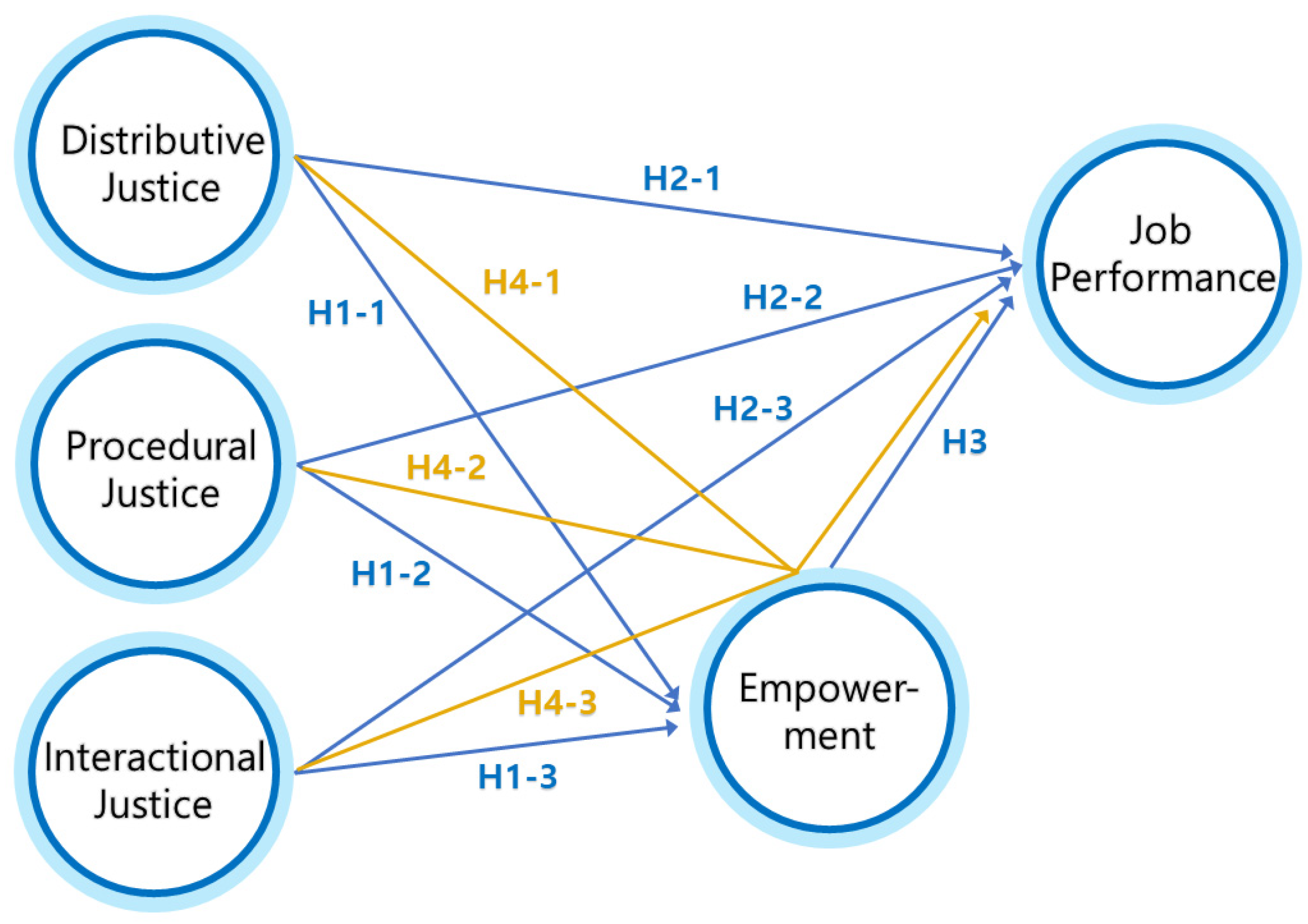

2. Literature Review, Research Hypotheses, and Model

2.1. Organizaional Justice

2.2. Empowerment

2.3. Research Hypotheses Development

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures and Data Analyses

3.3. Validity and Reliability

4. Results

4.1. Model Fit and Structural Model

4.2. Mediating Effect of Empowerment

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.K.; Yu, J.G. Examining the Process behind the Decision of Sports Fans to Attend Sports Matches at Stadiums Amid the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: The Case of South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y. The role of motivation, involvement, and experience in forming team loyalty of professional soccer supporters. Korean J. Sport Manag. 2019, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Ko, J.H. Spectator’s value cognition and expected-benefit factors on professional baseball sport star. Korean J. Phy. Edu. 2012, 51, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, E.; Kim, M.; Zhang, J.J. Exploring relationships among organizational culture, empowerment, and organizational citizenship behavior in the South Korean professional sport industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Charash, Y.; Spector, P.E. The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 278–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, J.E. Performance related pay: The importance of fairness. J. Ind. Relat. 2001, 43, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Law, K.S.; Bobko, P. The importance of justice perceptions on pay effectiveness: A two-year study of a skill-based pay plan. J. Manag. 1999, 25, 851–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. Organizational Justice: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. J. Manag. 1990, 16, 399–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.S. Inequity in social exchange. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965; Volume 2, pp. 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut, J.W.; Walker, L. Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Bies, R.; Moag, R. Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. In Research on Negotiation in Organizations; Lewicki, R.J., Sheppard, B.H., Bazerman, M.H., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1986; pp. 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Y.D. Structural Relationship among Organizational Culture, Empowerment, and Job Performance, and Comparison of Models-Focused on Professional Football Corporate Club and Citizen Club. Ph.D. Thesis, Kyonggi University, Suwon, Korea, 2017. Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, I.; Emirates, U.A. Employee empowerment and employee performance: An empirical study on selected banks in UAE. J. Appl. Manag. Investig. 2018, 7, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Aujoulat, I.; d’Hoore, W.; Deccache, A. Patient empowerment in theory and practice: Polysemy or cacophony? Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 66, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jameel, A.S.; Ahmad, A.R.; Mousa, T.S. Organizational justice and job performance of academic staff at public universities in Iraq. Sky. Bus. J. 2020, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Moazzezi, M.; Sattari, S.; Bablan, A.Z. Relationship between organizational justice and job performance of Payamenoor University Employees in Ardabil Province. Singap. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2014, 2, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Akram, T.; Lei, S.; Haider, M.J.; Hussain, S.T. The impact of organizational justice on employee innovative work behavior: Mediating role of knowledge sharing. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitasari, D.; Asbari, M.; Wijaya, M.R.; Yuwono, T. Effect of Organizational Justice on Organizational Commitment: Mediating Role of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Satisfaction. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Stud. (IJSMS) 2020, 3, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.J.; Ali, M. Corporate social responsibility, organizational justice and positive employee attitudes: In the context of Korean employment relations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, M.L.; Schminke, M. The role of overall justice judgments in organizational justice research: A test of mediation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A. Justice as economics in Aristotle’s Nicomachean ethics. Can. Political Sci. Rev. 2010, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, D.M.; Bardes, M.; Piccolo, R.F. Do servant-leaders help satisfy follower needs? An organizational justice perspective. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 17, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. Employee theft as a reaction to underpayment inequity: The hidden cost of pay cuts. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, K. The social context of organizational justice: Cultural, intergroup, and structural effects on justice behaviors and perceptions. In Justice in the Workplace: Approaching Fairness in Human Resource Management; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Aryee, S.; Budhwar, P.S.; Chen, Z.X. Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Judge, T.A.; Shaw, J.C. Justice and personality: Using integrative theories to derive moderators of justice effects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2006, 100, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G. Social Behavior: Its Elemental Forms; Harcourt: San Diego, CA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J.; Tyler, T.R. Why procedural justice in organizations? Soc. Justice Res. 1987, 1, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, G.S. What should be done with equity theory? In Social Exchange; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J.; Folger, R. Procedural justice, participation, and the fair process effect in groups and organizations. In Basic Group Processes; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; Fehr, R.; Yam, K.C.; Long, L.R.; Hao, P. Interactional justice, leader–member exchange, and employee performance: Examining the moderating role of justice differentiation. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 537–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouquereau, E.; Morin, A.J.; Huyghebaert, T.; Chevalier, S.; Coillot, H.; Gillet, N. On the value of considering specific facets of interactional justice perceptions. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Taking aim on empowerment research: On the distinction between individual and psychological conceptions. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1990, 18, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, S.E. Psychological empowerment and development. Edo J. Couns. 2009, 2, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengland, P.A. Empowerment: A conceptual discussion. Health Care Anal. 2008, 16, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, N.; Czuba, C.E. Empowerment: What is it. J. Ext. 1999, 37, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, N.A. Empowerment theory: Clarifying the nature of higher-order multidimensional constructs. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2014, 53, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.W.; Velthouse, B.A. Cognitive elements of empowerment: An “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1990, 15, 666–681. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, R.E.; Spreitzer, G.M. The road to empowerment: Seven questions every leader should consider. Organ. Dyn. 1997, 26, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gist, M.E. Self-efficacy: Implications for organizational behavior and human resource management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Kizilos, M.A.; Nason, S.W. A dimensional analysis of the relationship between psychological empowerment and effectiveness satisfaction, and strain. J. Manag. 1997, 23, 679–704. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Connell, J.P.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination in a work organization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J.E.; Judge, T.A. Self-concordance at work: Toward understanding the motivational effects of transformational leaders. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 554–571. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E. The experience of powerlessness in organizations. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1989, 43, 207–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuokkanen, L.; Leino-Kilpi, H.; Katajisto, J.; Heponiemi, T.; Sinervo, T.; Elovainio, M. Does organizational justice predict empowerment? Nurses assess their work environment. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2014, 46, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choo, J.Y.; Bae, J.H. An analysis of the structural relationship of organizational culture, organizational justice, empowerment and organizational effectiveness using structural equation models. Crisisonomy 2016, 12, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.B. Influence of organizational fairness perceived by revenue officers on empowerment and employee efforts. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2009, 9, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, B.L.; Shapiro, D.L.; Novelli, L.; Brett, J.M. Employee concerns regarding self-managing work teams: A multidimensional justice perspective. Soc. Justice Res. 1996, 9, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellins, R.S.; Wilson, R.; Katz, A.J.; Laughlin, P.; Day, C.R.; Price, D. Self-Directed Teams: A Study of Current Practice; DDI: Bridgeville, PA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, R.; Loon, K.W.; Yunus, N.A.S. Examining the relationship between organizational justice and job performance. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Ishaq, H.M.; Shaheen, M.A. Impact of organizational justice on job performance in libraries. Libr. Manag. 2015, 36, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasurdin, A.M.; Khuan, S.L. Organizational justice as an antecedent of job performance. Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus. 2007, 9, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.F.; Hsieh, T.S. The impacts of perceived organizational support and psychological empowerment on job performance: The mediating effects of organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetik, N. The effects of psychological empowerment on job satisfaction and job performance of tourist guides. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2016, 6, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechanova, M.R.M.; Alampay, R.B.A.; Franco, E.P. Psychological empowerment, job satisfaction and performance among Filipino service workers. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 9, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate analysis of data. Porto Alegre Bookm. 2005, 6, 89–127. [Google Scholar]

- Moorman, R.H. Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors: Do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehoff, B.P.; Moorman, R.H. Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 527–556. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Gracia, L.; Barbaranelli, C.; Jiménez, B.M. Spanish version of Colquitt’s organizational justice scale. Psicothema 2014, 26, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gürbüz, S.; Mert, I.S. Validity and reliability testing of organizational justice scale: An empirical study in a public organization. Rev. Public Adm. 2009, 42, 117–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hochwälder, J.; Brucefors, A.B. A psychometric assessment of a Swedish translation of Spreitzer’s empowerment scale. Scand. J. Psychol. 2005, 46, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraimer, M.L.; Seibert, S.E.; Liden, R.C. Psychological empowerment as a multidimensional construct: A test of construct validity. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1999, 59, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, J.P. The Concept and Understanding of Structural Equation Model; Hannarae Publishing: Seoul, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Experimental Designs Using ANOVA; Duxbury Press: Belmont, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, M.J. Influence of perceived organizational justice on empowerment, organizational commitment and turnover intention in the hospital nurses. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.S. Effect of domestic airline companies’ organizational justice on the quality of LMX, empowerment and the service oriented organizational citizenship behavior. Foodserv. Ind. J. 2014, 10, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, K.H. Effects of Perceived Organizational Justice on Empowerment, Organizational Commitment and Turnover Intention of Food Material Distribution Employee. Master’s Thesis, Catholic Kwandong University, Gangnueng, Korea, 2017. Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Rodell, J.B.; Long, D.M.; Zapata, C.P.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J. Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rawashdeh, E.T. Organizational justice and its impact upon job performance in the Jordanian customs department. Int. Manag. Rev. 2013, 9, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Z.; Abdullah, N.H.; Othayman, M.B.; Ali, M. The role of LMX in explaining relationships between organizational justice and job performance. J. Comput. 2019, 11, 144–160. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, O.D. Revisiting the impact of perceived empowerment on job performance: Results from front-line employees. Turizam 2015, 19, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Zaman, R.; Phil, M. Effect of empowerment on job performance: A study of software sector of Pakistan. Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.J.; Won, D.Y.; Kwag, M.S. The relationships between leader-member exchange quality, empowerment, and job performance of the fitness center instructors. Sports Sci. Res. 2016, 27, 88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, A. Fairness and wages in Mexico’s maquiladora industry: An empirical analysis of labor demand and the gender wage gap. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2011, 69, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temnitskii, A.L. Fairness in wages and salaries as a value orientation and a factor of motivation to work. Sociol. Res. 2007, 46, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, M.H. Perceived equity of salary policies. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rees, A. The role of fairness in wage determination. J. Labor Econ. 1993, 11, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bies, R.J.; Shapiro, D.L. Voice and justification: Their influence on procedural fairness judgments. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 31, 676–685. [Google Scholar]

- Kernan, M.C.; Hanges, P.J. Survivor reactions to reorganization: Antecedents and consequences of procedural, interpersonal, and informational justice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seon, Y.Y.; Jeong, Y.D. Analysis of the core competencies of Taekwondo instructors: Using Delphi Technique. J. Korean Sports Assoc. 2020, 18, 801–816. [Google Scholar]

| Scale Items | Standardized Loadings | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distributive justice | ||||

| Employees receive fair compensation according to their efforts and abilities. | 0.579 | 0.801 | 0.509 | 0.720 |

| Employees receive fair compensation as well as work performance. | 0.508 | |||

| Employees receive fair compensation as equivalently as assigned responsibilities. | 0.730 | |||

| Employees are rewarded for their degree of work experience. | 0.760 | |||

| Procedural justice | ||||

| The organization has a procedure to provide feedback on the results of the reward. | 0.851 | 0.904 | 0.759 | 0.870 |

| The organization has a procedure for accurate individual compensation. | 0.833 | |||

| The organization tends to listen to employees’ views regarding rewards. | 0.813 | |||

| Interactional justice | ||||

| The boss tends to respect my opinion in respect of decisions as to rewards. | 0.778 | 0.811 | 0.523 | 0.740 |

| In making decisions regarding compensation, the boss tries to rule out personal prejudices. | 0.544 | |||

| The boss is thoughtful and attentive to my decision concerning compensation. | 0.578 | |||

| In making decisions regarding compensation, the boss treats me in a straightforward manner. | 0.648 | |||

| Meaning | ||||

| My job performance is personally meaningful. | 0.887 | 0.881 | 0.714 | 0.851 |

| I am confident that I shall accomplish my business objectives. | 0.832 | |||

| I have autonomy in deciding how to do business. | 0.716 | |||

| Competence | ||||

| I feel rewarded for what I do. | 0.828 | 0.824 | 0.612 | 0.800 |

| I want to achieve higher goals than others. | 0.784 | |||

| I can control what happens in my department. | 0.654 | |||

| Self-determination | ||||

| What I do is important within the organization. | 0.698 | 0.777 | 0.537 | 0.705 |

| I can accomplish my work goals. | 0.658 | |||

| I maintain my opinion while doing business. | 0.644 | |||

| Impact | ||||

| My job is important to improve my career. | 0.848 | 0.827 | 0.620 | 0.791 |

| I am confident that I will push ahead with what I plan to in my organization. | 0.815 | |||

| I can make important decisions about the way organization works. | 0.592 | |||

| Job performance | ||||

| I am actively engaged in performing my duties. | 0.856 | 0.811 | 0.527 | 0.779 |

| I think my job performance contributes to the development of the team. | 0.655 | |||

| I tend to get recognition from my boss for performing my duties. | 0.765 | |||

| My job performance level is high compared to my colleagues. | 0.506 | |||

| DJ | PJ | IJ | Empowerment | JP | |

| DJ | 0.849 | ||||

| PJ | 0.614 ** | 0.933 | |||

| IJ | 0.260 ** | 0.230 ** | 0.860 | ||

| Empowerment | 0.514 ** | 0.470 ** | 0.424 ** | 0.978 | |

| JP | 0.504 ** | 0.454 ** | 0.424 ** | 0.578 ** | 0.883 |

| 95.0% Confidence Interval | |||||

| Parameter | Estimate | Lower | Upper | P | |

| DJ ←→ PJ | 0.614 | 0.533 | 0.695 | 0.000 | |

| DJ ←→ IJ | 0.260 | 0.161 | 0.359 | 0.000 | |

| DJ ←→ Empowerment | 0.514 | 0.426 | 0.602 | 0.000 | |

| DJ ←→ JP | 0.504 | 0.416 | 0.593 | 0.000 | |

| PJ ←→ IJ | 0.230 | 0.130 | 0.329 | 0.000 | |

| PJ ←→ Empowerment | 0.470 | 0.379 | 0.560 | 0.000 | |

| PJ ←→ JP | 0.454 | 0.363 | 0.545 | 0.000 | |

| IJ ←→ Empowerment | 0.424 | 0.331 | 0.516 | 0.000 | |

| IJ ←→ JP | 0.424 | 0.332 | 0.517 | 0.000 | |

| Empowerment ←→ JP | 0.578 | 0.495 | 0.662 | 0.000 | |

| Hypothesis | Path | Standardized Coefficient | C.R. | Supported? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1 | Distributive justice → Empowerment | 0.227 | 2.454 * | Yes |

| 1-2 | Procedural justice → Empowerment | 0.214 | 2.514 * | Yes |

| 1-3 | Interactional justice → Empowerment | 0.435 | 7.215 *** | Yes |

| 2-1 | Distributive justice → Job performance | 0.123 | 1.259 | No |

| 2-2 | Procedural justice → Job performance | 0.216 | 2.395 * | Yes |

| 2-3 | Interactional justice → Job performance | 0.203 | 2.941 ** | Yes |

| 3 | Empowerment → Job performance | 0.320 | 4.403 *** | Yes |

| Path. | Direct Effects without Mediator | Direct Effects with a Mediator (CI) | Indirect Effects (CI) | p | Mediation Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distributive justice → empowerment → job performance | 0.156 | 0.123 (−0.110 to 0.796) | 0.073 (−0.007 to 0.228) | 0.067 | Not supported |

| Procedural justice → empowerment → job performance | 0.301 *** | 0.216 (−0.181 to 0.457) | 0.069 (−0.002 to 0.219) | 0.060 | Not supported |

| Interactional justice → empowerment → job performance | 0.388 *** | 0.203 (−0.057 to 0.459) | 0.139 * (0.028 to 0.328) | 0.016 | Supported (Full mediation) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.-K.; Jeong, Y. Developing the Healthy and Competitive Organization in the Sports Environment: Focused on the Relationships between Organizational Justice, Empowerment and Job Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179142

Kim S-K, Jeong Y. Developing the Healthy and Competitive Organization in the Sports Environment: Focused on the Relationships between Organizational Justice, Empowerment and Job Performance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(17):9142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179142

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Suk-Kyu, and Yunduk Jeong. 2021. "Developing the Healthy and Competitive Organization in the Sports Environment: Focused on the Relationships between Organizational Justice, Empowerment and Job Performance" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 17: 9142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179142

APA StyleKim, S.-K., & Jeong, Y. (2021). Developing the Healthy and Competitive Organization in the Sports Environment: Focused on the Relationships between Organizational Justice, Empowerment and Job Performance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 9142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179142