Exploring the Leadership–Engagement Nexus: A Moderated Meta-Analysis and Review of Explaining Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Positive Leadership Styles

1.2. Work Engagement

1.3. Leadership and Engagement: Theoretical Explanations

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Studies

3.2. Leadership Questionnaires

3.3. Engagement Questionnaires

3.4. General Results of the Meta-Analysis

3.5. Additional Analyses: Moderated Meta-Analysis

3.6. Conclusion

4. Theoretical Analysis: The Core of Positive Leader Behaviour

4.1. Shared Themes

4.2. Conclusion

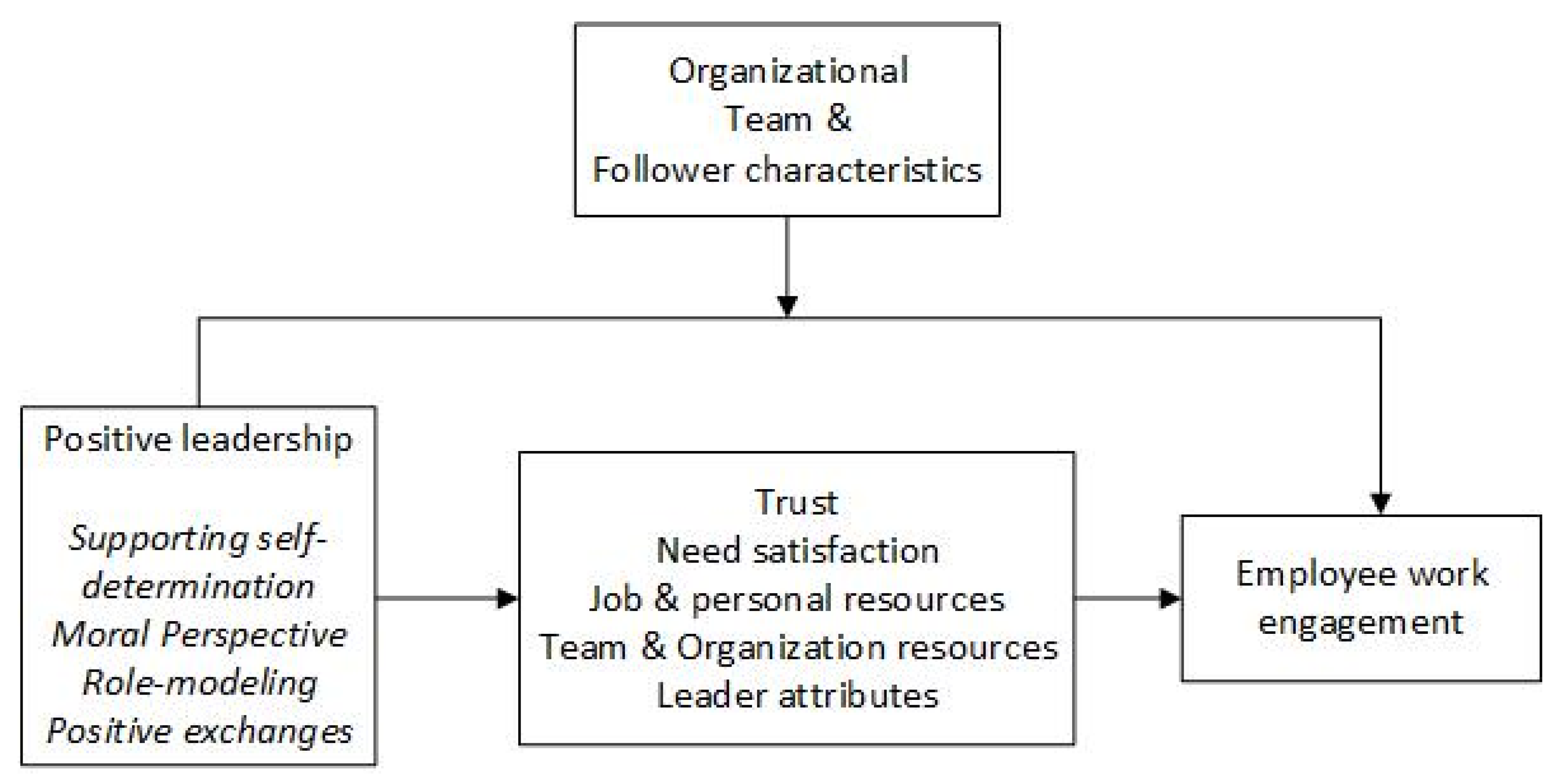

5. Building the Research Model: Mediating and Moderating Mechanisms

5.1. Moderating Mechanisms

5.2. Mediating Mechanisms

- Psychological needs. As can be seen in Table 5, most studies (13) related to psychological needs. First, several studies found psychological needs as conceptualized by self-determination theory [63] to be a mediator in the relationship between positive leadership styles and engagement, i.e., competence need satisfaction [129], relatedness need satisfaction [129], and total psychological need satisfaction [47,125]. Second, four studies investigated work meaningfulness as a mediator. This is not surprising, since Kahn [58] already proposed that psychological meaningfulness, along with availability and safety, were precursors of work engagement. Both Kahn [58] and SDT proposed theories concerning antecedents for engagement (see Section 1), which can be influenced by positive leadership.Third, psychological empowerment was found to be a significant mediator in five studies with different positive leadership styles. Since this is a relatively new concept, we will provide the definition: ‘increased intrinsic task motivation manifested in a set of four cognitions reflecting an individual’s orientation to his or her work role: competence, impact, meaning, and self-determination’ [157] (p. 1443). Competence is defined as ‘an individual’s belief in his or her capability to perform activities with skill’ (p. 1443). Having an impact is defined as ‘the degree to which an individual can influence strategic, administrative, or operating outcomes at work’ (p. 1444). The third element, meaning, is defined as ‘the value of a work goal or purpose, judged in relation to an individual’s own ideals or standard’ (p. 1443). Lastly, the self-determination component is defined as ‘an individual’s sense of having choice in initiating and regulating action’ (p. 1443). The definitions hint at meaningfulness, competence, autonomy, as well as full self-determination; therefore, we categorized this concept under the label ‘psychological needs’.In sum, these studies indicate that the satisfaction of psychological needs may be the primary mechanism through which positive leadership influences engagement: leadership that enhances the fulfilment of psychological needs (SDT) or psychological conditions [58] enhances work engagement.

- Trust. Trust in the leader (k = 8) or organization (k = 2) was found to be a mediator in ten different studies. Trust can be defined as ‘a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behaviours of another’ [158] (p. 395). Trust can be related to engagement in several ways. Macey and Schneider [62] point out that ‘engaged employees invest their energy, time, or personal resources, trusting that the investment will be rewarded (intrinsically or extrinsically) in some meaningful way’ (p. 22). This is similar to what social exchange theory posits (SET [68]; see introduction). In this view, the exchange relationship between the leader and employee is maintained through a state of interdependence: there is an expectation of reciprocation of favours, work, or support based on mutual long-term investment, socio-emotional give-and-take, and trust. Indeed, several other authors see (interpersonal) trust as a part of a quality social exchange relationship [159,160]. This relation-based perspective on trust is, therefore, based on mutual obligation [69,161]. When employees trust leaders, this aids in the development of high-quality exchange relationships (LMX; [162]), which may also encourage employees to spend more (personal) resources and energy on job tasks [163,164].

- Job and personal resources. In total, nine personal and nine job resources were found to be significant mediators in the relationship between different positive leadership styles and engagement. With regards to job resources, job autonomy and ‘job resources in general’ were most researched (three studies with significant results; see Table 5). Next, the overall congruence of person and job was found to be a mediator twice [80,143]. Only one study found a positive mediating effect of role clarity [1]. With regards to personal resources, only optimism and self-efficacy were found to be significant mediators in two studies, other personal resources were positive effect [147], work–life enrichment [148], project identification [149], practicing core values [150], and psychological capital [151].These results are in line with expectations based on the job demands resources model (JD-R model), which posits the importance of personal and job resources for work engagement. Recently, engaging leadership was added to the model [3], indicating that leadership that inspires, connects, and strengthens followers has an indirect, positive effect on their levels engagement through the allocation of job resources and job demands.

- Organizational and team resources. Seven studies investigated mediators at levels other than the individual employee–leader level. Six of them were organizational-level mediators. Two studies focused on organizational identification [117,140], while two other studies focused on social corporate goals as mediators: i.e., corporate social responsibility [153] and perceived societal impact [154]. Only one study investigated organizational justice [152] and ‘promotive organization-based psychological ownership’ [155]. At the group level, only one study found group identification to be a mediator in the relationship between transformational leadership and engagement [154].These results provide evidence for the importance of incorporating multilevel mediators when researching the relationship between positive leadership styles and engagement, specifically organizational identification and social corporate goals.

5.3. Summary

6. Discussion

6.1. Limitations and Future Research

6.2. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author (Year) | Leadership Style | Leadership Measure | Alpha | Engagement Measure | Alpha | Country | N | Industry | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abidin (2017) [37] | Authentic | ALQ 16 (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.76 | WES 18 (Rich et al., 2010) | 0.88 | Malaysia | 260 | Budget hotels | 0.32 |

| Adil and Kamal (2016) [177] | Authentic | ALQ 16 (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.93 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.95 | Pakistan | 500 | University teachers | 0.29 |

| Albrecht and Andreetta (2011) [53] | Empowering | Empowering subscale (Pearce and Sims, 2002) | 0.91 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.87 | Australia | 139 | Community health service | 0.34 |

| Alok and Israel (2012) [155] | Authentic | ALQ 16 (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.95 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.88 | India | 117 | Working professionals | 0.47 |

| Arfat et al. (2017) [119] | Transformational | MLQ 5x (Bass and Avolio, 1995) | 0.81 | Engagement (Saks, 2006) | 0.83 | Pakistan | 700 | Banking | 0.58 |

| Azanza et al. (2015) [178] | Authentic | ALQ (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.89 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.89 | Spain | 623 | Various | 0.54 |

| Bae et al. (2013) [179] | Transformational | MLQ 12 (Bass and Avolio, 1992) | 0.97 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2003) | 0.92 | US | 304 | School teachers | 0.34 |

| Bass et al. (2016) [180] | Transformational | 4 items (adapted from Pearce and Sims, 2002) | 0.91 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.84 | US | 728 | School employees | 0.28 |

| Besieux et al. (2015) [153] | Transformational | MLQ 13 items (Avolio et al., 1999) | 0.95 | 18 items (Towers Watson, 2010) | 0.86 | Belgium | 5313 | Banking | 0.48 |

| Bird et al. (2012) [181] | Authentic | ALQ (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.84 | Q12 Gallup (Buckingham and Coffham, 1999) | 0.88 | US | 633 | Teaching staff | 0.61 |

| Breevaart et al. (2014) [126] | Transformational | TLI (Podsakoff et al., 1990) | 0.91 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.94 | Netherlands | 162 | Various | 0.53 |

| Bui et al. (2017) [145] | Transformational | MLQ 20 (Avolio and Bass, 2004) | 0.97 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.96 | China | 691 | Various | 0.64 |

| Buil et al. (2016) [182] | Transformational | 7 items (Carless et al., 2000) | 0.90 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2003) | 0.89 | Spain | 323 | Receptionists in hotels | 0.51 |

| Cerne et al. (2014) [85] | Authentic | ALI 16 (Neider and Schriesheim, 2011) | 0.94 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.75 | Slovenia | 171 | Manufacturing and processing | 0.32 |

| Cheng et al. (2014) [117] | Ethical | ELS 10 items (adapted Brown et al., 2005) | 0.93 | WES 18 items (Rich et al., 2010) | 0.96 | Taiwan | 670 | Economic research | 0.48 |

| De Clercq et al. (2014) [123] | Servant | SLQ 28 items (Liden et al., 2008) | 0.96 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.90 | Ukraine | 263 | IT companies | 0.50 |

| De Klerk and Stander (2014) [51] | Empowering | LEBQ (Konczak et al., 2000) | 0.91 | WES (Rothmann, 2010) | 0.90 | SA | 322 | Various production areas | 0.36 |

| Demirtas (2015) [127] | Ethical | ELS 10 (Brown et al., 2005) | 0.95 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.88 | Turkey | 418 | Firm in aviation logistics | 0.49 |

| Demirtas (2017) [128] | Ethical | ELS 10 (Brown et al., 2005) | 0.93 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.92 | US | 317 | Aviation maintenance | 0.48 |

| Den Hartog and Belschak (2012) [183] | Ethical | ELS 10 (Brown et al., 2005) | 0.91 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004) | 0.92 | Netherlands | 167 | Various jobs | 0.54 |

| Den Hartog and Belschak (2012) [183] | Ethical | ELS 10 (Brown et al., 2005) | 0.88 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004) | 0.91 | Netherlands | 200 | Various jobs | 0.49 |

| Ding et al. (2017) [151] | Transformational | MLQ 5x (Bass and Avolio, 1994) | 0.94 | WES 9 (Rich et al., 2010; He et al., 2014) | 0.90 | China | 162 | Infrastructure projects | 0.27 |

| Engelbrecht et al. (2014) [70] | Ethical | LES 17 (this study) | 0.97 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2003) | 0.89 | South Africa | 204 | Various orgs | 0.60 |

| Enwereuzor et al. (2016) [124] | Transformational | TLI 22 (Podsakoff et al., 1990) | 0.83 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.89 | Nigeria | 224 | Hospital nurses | 0.50 |

| Espinoza-Parra et al. (2015) [184] | Transformational | MLQ 5x short (Molero et al., 2010) | 0.95 | UWES 17 (Salanova et al., 2000) | 0.90 | Chile | 985 | Police officers | 0.45 |

| Ghadi et al. (2013) [132] | Transformational | GTL (Carless et al., 2000) | 0.95 | UWES 9 (Bakker, 2009) | 0.95 | Australia | 530 | Various | 0.69 |

| Giallonardo et al. (2010) [185] | Authentic | ALQ 16 (Avolio et al., 2007) | 0.91 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2003) | 0.86 | Canada | 170 | Registered nurses | 0.21 |

| Goswami et al. (2016) [186] | Transformational | TLQ 24i (Podsakoff et al., 1990) | 0.87 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.93 | US | 235 | Consulting | 0.08 |

| Gözükara and Simsek (2015) [141] | Transformational | MLQ 5x (Bass and Avolio, 1995) | 0.96 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2003) | 0.90 | Turkey | 101 | Academic staff | 0.34 |

| Gözükara and Simsek (2016) [142] | Transformational | MLQ 5x (Bass and Avolio, 1995) | 0.96 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2003) | 0.90 | Turkey | 252 | Higher education | 0.47 |

| Hansen et al. (2014) [79] | Transformational | TFL 15 (Rafferty and Griffin, 2004) | 0.96 | UWES 9 items (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.92 | US | 451 | International firm | 0.42 |

| Hassan and Ahmed (2011) [140] | Authentic | ALQ 19 items (Avolio et al., 2007) | 0.91 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004) | 0.91 | Malaysia | 395 | Banking | 0.41 |

| Hawkes et al. (2017) [143] | Transformational | LBS (Podsakoff et al., 1990) | 0.96 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.93 | Australia | 277 | Various | 0.47 |

| Hayati et al. (2014) [187] | Transformational | MLQ 20 (Bass and Avolio, 1997) | 0.91 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.73 | Iran | 240 | Nurses | 0.70 |

| Hsieh and Wang (2015) [137] | Authentic | ALQ (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.88 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.95 | Taiwan | 345 | Manufacturing and service | 0.61 |

| Jiang and Men (2017) [149] | Authentic | Neider and Schriesheim (2011) | 0.97 | 11 items (Kang 2014; Saks, 2006) | 0.96 | US | 391 | Various | 0.55 |

| Joo et al. (2016) [188] | Authentic | ALQ (Avolio et al., 2005) | 0.88 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.91 | Korea | 599 | Knowledge workers | 0.47 |

| Khuong and Dung (2015) [135] | Ethical | ELS 10 (Brown et al., 2005) | 0.93 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.90 | Vietnam | 312 | Technicians | 0.37 |

| Khuong and Yen (2014) [189] | Ethical | ELS 10 (Brown et al., 2005) | 0.93 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.92 | Vietnam | 269 | 5 industries | 0.48 |

| Kulophas et al. (2018) [147] | Authentic | ALQ (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.92 | UWES 18 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.93 | Thailand | 605 | Teachers several schools | 0.36 |

| Kopperud et al. (2014) [39] | Transformational | MLQ 20 (Bass and Avolio, 1990) | 0.82 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.92 | Norway | 1226 | Financial services | 0.44 |

| Kopperud et al. (2014) [39] | Transformational | MLQ 20 (Bass and Avolio, 1990) | 0.91 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.89 | Norway | 291 | Audit company | 0.34 |

| Kovjanic et al. (2013) [130] | Transformational | MLQ 19 (Bass and Avolio, 1995) | 0.97 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.95 | Germany | 190 | Various | 0.71 |

| Lee et al. (2017) [133] | Empowering | LBQ (Pearce and Sims, 2002) | 0.86 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.91 | Malaysia | 134 | Various | 0.37 |

| Lewis and Cunningham (2016) [190] | Transformational | TFL 18 (Rafferty and Griffin, 2004) | 0.97 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2003) | 0.88 | US | 120 | Nurses | 0.46 |

| Manning (2016) [191] | Transformational | MLQ 5x (Bass and Avolio, 1995) | 0.91 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2003) | 0.90 | US | 441 | Staff nurses, 3 hospitals | 0.37 |

| Mauno et al. (2016) [192] | Transformational | GTL 7 items (Carless et al., 2000) | 0.94 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.93 | Finland | 3466 | Nurses | 0.29 |

| Mayr (2017) [155] | Transformational | MLQ 20 (Bass and Avolio, 1995) | 0.96 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.93 | Germany | 213 | Volunteer fire fighters | 0.40 |

| Mendes and Stander (2011) [1] | Empowering | LEBQ (Konczak et al., 2000) + 2 items info sharing (Arnold et al., 2000) | 0.88 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.83 | South Africa | 179 | Chemical org | 0.25 |

| Mitonga-Monga et al. (2016) [193] | Ethical leadership | ELS 10 (Brown et al., 2005) | 0.91 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.90 | SA | 839 | Railway transportation | 0.59 |

| Moss (2009) [6] | Transformational | TFL 15 (Rafferty and Griffin, 2004) | 0.89 | UWES 9 vigor and dedication | 0.87 | Australia | 160 | Various | 0.35 |

| Mozammel and Haan (2016) [194] | Transformational | MLQ 20 (Avolio and Bass, 2004) | 0.91 | UWES 9 (Bakker and Schaufeli, 2003) | 0.89 | Bangladesh | 128 | Banking | 0.18 |

| Ochalski (2016) [195] | Transformational | MLQ 5x (Avolio and Bass, 2004) | 0.91 | UWES 17 (Bakker, 2011) | 0.90 | US | 157 | Pharmaceutical | 0.67 |

| Oh et al. (2018) [151] | Authentic | ALQ 16 (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.75 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.80 | South Korea | 281 | 3 big corporations | 0.47 |

| Park et al. (2017) [152] | Empowering | 12 items (Ahearne et al., 2005) | 0.93 | WES 18 (Rich et al., 2010) | 0.97 | South Korea | 285 | 8 large firms | 0.59 |

| Perko et al. (2016) [4] | Authentic | ALQ 16 (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.94 | UWES 9 vigor (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.87 | Finland | 262 | Various, public sector | 0.31 |

| Popli and Rizvi (2015) [102] | Transformational | MLQ 5x (Bass and Avolio, 1995) | 0.93 | DDI E3 (Phelps, 2009) | 0.90 | India | 106 | Service sector | 0.59 |

| Popli and Rizvi (2016) [196] | Transformational | MLQ 5x (Bass and Avolio, 1995) | 0.90 | DDI E3 (Phelps, 2009) | 0.90 | India | 329 | Service sector | 0.42 |

| Prochazka et al. (2017) [146] | Transformational | CLQ (Prochazka et al., 2016) based on MLQ | 0.96 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli, 2015) | 0.92 | Czech Republic | 307 | Various | 0.44 |

| Pourbarkhordari et al. (2016) [197] | Transformational | 16 items (Wang and Howell, 2010) | 0.94 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.81 | China | 202 | Telecommunications | 0.40 |

| Qin et al. (2014) [121] | Ethical leadership | ELS 10 (Brown et al., 2005) | 0.95 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.90 | China | 285 | Tourism | 0.65 |

| Sahu et al. (2018) [104] | Transformational | MLQ 12 (Bass and Avolio, 1992) | 0.96 | Gallup 12 (Mann and Ryan, 2014) | 0.88 | India | 405 | IT | 0.54 |

| Salanova et al. (2011) [145] | Transformational | MLQ 20 (Bass and Avolio, 1997) | 0.78 | UWES 17 vigor and dedication (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.84 | Portugal | 280 | Nurses | 0.18 |

| Scheepers and Elstob (2016) [120] | Authentic | ALQ (Avolio et al., 2007) | 0.90 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.54 | South Africa | 81 | Financial service orgs | 0.52 |

| Schmitt et al. (2016) [198] | Transformational | 11 items Dutch scale (De Hoogh et al., 2004) | 0.94 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.91 | Netherlands | 148 | Various | 0.37 |

| Seco and Lopes (2013) [199] | Authentic | ALQ (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.89 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.94 | Portugal | 326 | Teachers several schools | −0.57 |

| Shu et al. (2015) [125] | Authentic | ALI 16 (Neider and Schriesheim, 2011) | 0.87 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.91 | Taiwan | 350 | Chinese workers | 0.18 |

| Song et al. (2013) [200] | Transformational | MLQ 12 (Bass and Avolio, 1992) | 0.91 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.95 | US | 284 | CTE teachers | 0.34 |

| Song et al. (2012) [201] | Transformational | MLQ 6x 12 (Bass and Avolio, 1992) | 0.85 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.74 | Korea | 432 | 6 for-profit orgs | 0.38 |

| Sousa and van Dierendonck (2014) [118] | Servant | SLS 30 items (van Dierendonck and Nuijten, 2011) | 0.79 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.90 | Portugal | 1107 | Two merging companies | 0.22 |

| Sousa and van Dierendonck (2017) [202] | Servant | SLS 30 items (van Dierendonck and Nuijten, 2011) | 0.93 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.94 | Portugal | 236 | Various | 0.55 |

| Stander et al. (2015) [72] | Authentic | ALI (Neider and Schriesheim, 2011) | 0.93 | UWES 8 items (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.90 | South Africa | 633 | 27 Hospitals | 0.42 |

| Strom et al. (2014) [16] | Transformational | MLQ 20 (Bass and Avolio, 1990) | 0.97 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.96 | US | 348 | Various | 0.44 |

| Tims et al. (2011) [203] | Transformational | MLQ 12 (Bass and Avolio, 1990) | 0.85 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.89 | Netherlands | 42 | Various, 2 different orgs | 0.35 |

| van Dierendonck et al. (2014) [47] | Servant | SL 14 (Ehrhardt, 2004) | 0.93 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.94 | Netherlands | 200 | Support staff university | 0.49 |

| van Schalkwyk et al. (2010) [204] | Empowering | LEBQ (Konczak et al., 2000) | 0.96 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.93 | South Africa | 168 | Petrochemical lab | 0.39 |

| Vincent-Höper et al. (2012) [205] | Transformational | MLQ 5x, 20 items (Bass and Avolio, 1995) | 0.97 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.95 | Germany | 1132 | Various | 0.46 |

| Wang and Hsieh (2013) [71] | Authentic | ALQ (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.94 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.95 | Taiwan | 386 | Manufacturing and service | 0.58 |

| Wang et al. (2017) [148] | Transformational | TLI 22 (Podsakoff et al., 1990) | 0.92 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.90 | China | 422 | IT company | 0.47 |

| Wefald et al. (2011) [206] | Transformational | GTL 7 items (Carless et al., 2000) | 0.95 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.93 | Netherlands | 382 | Finances | 0.27 |

| Wei et al. (2016) [207] | Authentic | ALQ (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.92 | UWES (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004) | 0.92 | China | 248 | Not specified | 0.35 |

| Wihuda et al. (2017) [208] | Empowering | 12 items (Ahearne et al., 2005) | 0.94 | UWES 17 (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2004) | 0.96 | Indonesia | 121 | Hotels | 0.29 |

| Whitford and Moss (2009) [209] | Transformational | TFL 15 vision and recognition (Rafferty and Griffin, 2004) | 0.91 | UWES 17 vigor and dedication (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.89 | Australia | 165 | Various | 0.22 |

| Wong et al. (2010) [138] | Authentic | ALQ (Avolio et al., 2007) | 0.97 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.90 | Canada | 280 | Registered nurses | 0.28 |

| Zhou et al. (2018) [129] | Empowering | 10 items (Pearce and Sims, 2002) | 0.84 | UWES 9 (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.81 | China | 220 | 11 hotels | 0.33 |

| Zhu et al. (2009) [122] | Transformational | MLQ 5x (Bass and Avolio, 1997) | 0.84 | GWA 12 items (Harter et al., 2002) | 0.86 | South Africa | 140 | Various | 0.58 |

| Questionnaire | Average Alpha | Times Substituted |

|---|---|---|

| UWES 9 items (Schaufeli et al., 2006) | 0.89 | 4× |

| UWES 17 items (Schaufeli et al., 2002) | 0.90 | 6× |

| Leadership Questionnaire | Average Alpha | Times Substituted |

|---|---|---|

| Transformational leadership | ||

| GTL (Carless et al., 2000) | 0.95 | 1× |

| MLQ 20 (Bass and Avolio, 1995) | 0.91 | 5× |

| Authentic leadership | ||

| ALQ (Walumbwa et al., 2008) | 0.89 | 1× |

| Ethical leadership | ||

| ELS (Brown et al., 2005) | 0.93 | 1× |

References

- Mendes, F.; Stander, M.W. Positive organisation: The role of leader behaviour in work engagement and retention. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2011, 37, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rodriguez, A.; Rodriguez, Y. Metaphors for today’s leadership: VUCA world, millennial and “Cloud Leaders”. J. Manag. Dev. 2015, 34, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. Engaging leadership in the job demands-resources model. Career Dev. Int. 2015, 20, 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perko, K.; Kinnunen, U.; Tolvanen, A.; Feldt, T. Investigating occupational well-being and leadership from a person-centred longitudinal approach: Congruence of well-being and perceived leadership. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.D.; Hitt, M.A. Achieving and maintaining strategic competitiveness in the 21st century: The role of strategic leadership. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1999, 13, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, S. Cultivating the Regulatory Focus of Followers to Amplify Their Sensitivity to Transformational Leadership. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2008, 15, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, P.; Ruiz, C.; Martinez-Cañas, R. Improving the “Leader–Follower” Relationship: Top Manager or Supervisor? The Ethical Leadership Trickle-Down Effect on Follower Job Response. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 99, 587–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Law, K.S.; Hackett, R.D.; Wang, D.; Chen, Z.X. Leader-Member Exchange as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Transformational Leadership and Followers’ Performance and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, M.; Coffman, C. First Break All the Rules: What the World’s Greatest Managers Do Differently; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, J.; Harter, J.K. It’s the Manager: Gallup Finds the Quality of Managers and Team Leaders is the Single Biggest Factor in Your Organization’s Long-Term Success; Gallup Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, J.W. Strategic Employee Surveys: Evidence-Based Guidelines for Driving Organizational Success; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Salanova, M.; Agut, S.; Peiro, J.M. Linking Organizational Resources and Work Engagement to Employee Performance and Customer Loyalty: The Mediation of Service Climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I.; Cooper, C. Well-Being: Productivity and Happiness at Work; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B. A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources and consequences. In Work Engagement: The Essential Theory and Research; Bakker, A.B., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Strom, D.L.; Sears, K.L.; Kelly, K.M. Work engagement: The roles of organizational justice and leadership style in predicting engagement among employees. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2013, 21, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.B.; Tran, T.B.H.; Park, B.I. Inclusive Leadership and Work Engagement: Mediating Roles of Affective Organizational Commitment and Creativity. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2015, 43, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decuypere, A.; Schaufeli, W. Leadership and work engagement: Exploring explanatory mechanisms. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 34, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.A.; Byrne, M.; Flood, B. Linking Ethical Leadership to Employee Well-Being: The Role of Trust in Supervisor. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, Q.; Nawab, S.; Hamstra, M.R.W. Does Authentic Leadership Predict Employee Work Engagement and In-Role Performance? Considering the role of learning goal orientation. J. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 15, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, L. How can personal development lead to increased engagement? The roles of meaningfulness and perceived line manager relations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 30, 1203–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.N.; Liao, H. How do leader–member exchange quality and differentiation affect performance in teams? An integrated multilevel dual process model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 847–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biggs, A.; Brough, P.; Barbour, J.P. Relationships of individual and organizational support with engagement: Examining various types of causality in a three-wave study. Work. Stress 2014, 28, 236–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Developing Transformational Leadership: 1992 and Beyond. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1990, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C.M.; Lucianetti, L.; Bhave, D.P.; Christian, M.S. “You wouldn’t like me when I’m sleepy”: Leaders’ sleep, daily abusive supervision, and work unit engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1419–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Liao, C.; Meuser, J. Servant Leadership and Serving Culture: Influence on Individual and Unit Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Schaubroeck, J.; Avolio, B.J. RETRACTED: Psychological processes linking authentic leadership to follower behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bartol, K.M. Linking Empowering Leadership and Employee Creativity: The Influence of Psychological Empowerment, Intrinsic Motivation, and Creative Process Engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.B.; Tesluk, P.E.; Marrone, J.A. Shared leadership in teams: An investigation of antecedent conditions and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1217–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Cenkci, A.T.; Özçelik, G. Leadership Styles and Subordinate Work Engagement: The Moderating Impact of Leader Gender. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2015, 7, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, K.N.; Diab, D.L. Humble Leadership: Implications for Psychological Safety and Follower Engagement. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2016, 10, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G. Leadership in Organizations. In Upper Saddle River; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Derue, D.S.; Nahrgang, J.D.; Wellman, N.; Humphrey, S. Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: An integration and meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 7–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowold, J.; Borgmann, L.; Diebig, M. A “Tower of Babel”?—Interrelations and structure of leadership constructs. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2015, 36, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, R.K.; Aguinis, H. Leadership behaviors and follower performance: Deductive and inductive examination of theoretical rationales and underlying mechanisms. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 38, 558–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, S.N.S.Z. The effect of perceived authentic leadership on employee engagement. J. Tour. Hosp. Environ. Manag. 2017, 2, 429–447. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M.; Jung, D.I. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire Suggestions for modi cation arose when a. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 72, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopperud, K.H.; Martinsen, L.; Humborstad, S.I.W. Engaging Leaders in the Eyes of the Beholder: On the Relationship between Transformational Leadership, Work Engagement, Service Climate, and Self–Other Agreement. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2013, 21, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Steidlmeier, P. Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Weber, T.J. Leadership: Current Theories, Research, and Future Directions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Wernsing, T.S.; Peterson, S.J. Authentic Leadership: Development and Validation of a Theory-Based Measure. J. Manag. 2007, 34, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernis, M.H.; Goldman, B.M. A Multicomponent Conceptualization of Authenticity: Theory and Research. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 283–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, H.; Anseel, F.; Dimitrova, N.G.; Sels, L. Mindfulness, authentic functioning, and work engagement: A growth modeling approach. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 82, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Zhao, H.; Henderson, D. Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, R.K. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness; Paulist Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- van Dierendonck, D.; Stam, D.; Boersma, P.; de Windt, N.; Alkema, J. Same difference? Exploring the differential mechanisms linking servant leadership and transformational leadership to follower outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 544–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dierendonck, D.; Nuijten, I. The Servant Leadership Survey: Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Measure. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 26, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L.K.; Brown, M.; Hartman, L.P. A Qualitative Investigation of Perceived Executive Ethical Leadership: Perceptions from Inside and Outside the Executive Suite. Hum. Relat. 2003, 56, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Klerk, S.; Stander, M.W. Leadership empowerment behaviour, work engagement and turnover intention: The role of psychological empowerment. J. Posit. Manag. 2014, 5, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konczak, L.J.; Stelly, D.J.; Trusty, M.L. Defining and Measuring Empowering Leader Behaviors: Development of an Upward Feedback Instrument. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 60, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, S.L.; Andreetta, M. The influence of empowering leadership, empowerment and engagement on affective commitment and turnover intentions in community health service workers: Test of a model. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2011, 24, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, T.; Stander, M.W.; Latif, J. Investigating positive leadership, psychological empowerment, work engagement and satisfaction with life in a chemical industry. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2015, 41, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.; Bakker, A. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.; Bakker, A.; Salanova, M. The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire A Cross-National Study. Educational and Psychological Measurement. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Bakker, A.B., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and t. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Psychol. Modul. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcock-Roberson, M.E.; Strickland, O.J. The Relationship between Charismatic Leadership, Work Engagement, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. J. Psychol. 2010, 144, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, B.L.; Lepine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job Engagement: Antecedents and Effects on Job Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, W.H.; Schneider, B. The meaning of employee engagement. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 1, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can. Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Broeck, A.; Vansteenkiste, M.; De Witte, H. Self-determination theory: A theoretical and empirical overview in occupational health psychology. In Occupational Health Psychology: European Perspectives on Research, Education, and Practice; Houdmont, J., Leka, S., Eds.; Nottingham University Press: Nottingham, UK, 2008; pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hoch, J.E.; Bommer, W.H.; Dulebohn, J.H.; Wu, D. Do Ethical, Authentic, and Servant Leadership Explain Variance Above and Beyond Transformational Leadership? A Meta-Analysis. J. Manag. 2016, 44, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.; Van Emmerik, H.; Euwema, M. Crossover of Burnout and Engagement in Work Teams. Work. Occup. 2006, 33, 464–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M.; Tetrick, L.E.; Lynch, P.; Barksdale, K. Social and Economic Exchange: Construct Development and Validation. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 837–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Power and Exchange in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Engelbrecht, A.S.; Heine, G.; Mahembe, B. The influence of integrity and ethical leadership on trust in the leader. Manag. Dyn. S. Afr. Inst. Manag. Sci. 2015, 24, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.-S.; Hsieh, C.-C. The effect of authentic leadership on employee trust and employee engagement. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2013, 41, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stander, F.W.; De Beer, L.T.; Stander, M.W. Authentic leadership as a source of optimism, trust in the organisation and work engagement in the public health care sector. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G.C.; McCauley, K.D.; Gardner, W.L.; Guler, C.E. A meta-analytic review of authentic and transformational leadership: A test for redundancy. Leadersh. Q. 2016, 27, 634–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G.C.; Gooty, J.; Ross, R.L.; Williams, C.E.; Harrington, N.T. Construct redundancy in leader behaviors: A review and agenda for the future. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carasco-Saul, M.; Kim, W.; Kim, T. Leadership and Employee Engagement: Proposing Research Agendas through a Review of Literature. Human Resource Development Review. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2014, 14, 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuck, B.; Herd, A.M. Employee Engagement and Leadership: Exploring the Convergence of Two Frameworks and Implications for Leadership Development in HRD. Human Resource Development Review. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2012, 11, 156–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D.V. The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Steffens, N.; Haslam, A.; Reicher, S.D.; Platow, M.J.; Fransen, K.; Yang, J.; Ryan, M.K.; Jetten, J.; Peters, K.; Boen, F. Leadership as social identity management: Introducing the Identity Leadership Inventory (ILI) to assess and validate a four-dimensional model. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 1001–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.M.; Byrne, Z.S.; Kiersch, C.E. How interpersonal leadership relates to employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 953–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamford, M.; Wong, C.A.; Laschinger, H. The influence of authentic leadership and areas of worklife on work engagement of registered nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 21, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Derks, D. Who takes the lead? A multi-source diary study on leadership, work engagement, and job performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, N.K.; Haslam, S.A.; Kerschreiter, R.; Schuh, S.C.; van Dick, R. Leaders Enhance Group Members’ Work Engagement and Reduce Their Burnout by Crafting Social Identity. Z. Fur Pers. 2014, 28, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, M.R.; Bakker, A.B.; Dollard, M.F. Empowering leaders optimize working conditions for engagement: A multilevel study. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.E.; Schmidt, F.L. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Černe, M.; Dimovski, V.; Marič, M.; Penger, S.; Škerlavaj, M. Congruence of leader self-perceptions and follower perceptions of authentic leadership: Understanding what authentic leadership is and how it enhances employees’ job satisfaction. Aust. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R.; DiMatteo, M.R. Meta-Analysis: Recent Developments in Quantitative Methods for Literature Reviews. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, D.A.; Harrison, D.A.; Carpenter, N.C.; Rariden, S.M. Construct Mixology: Forming New Management Constructs by Combining Old Ones. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 943–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. The Combination of Estimates from Different Experiments. Biometrics 1954, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. Confidence intervals for the amount of heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2007, 26, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitener, E.M. Confusion of Confidence Intervals and Credibility Intervals in Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Piccolo, R.F. Transformational and Transactional Leadership: A Meta-Analytic Test of Their Relative Validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, H.R.; Sutton, A.J.; Borenstein, M. Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, R. The ‘file drawer problem’ and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G.C.; Kepes, S.; McDaniel, M.A. Publication bias: Understanding the myths concerning threats to the advancement of science. In More Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends; Lance, C.E., Vandenberg, R.J., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 36–64. [Google Scholar]

- Duval, S.; Tweedie, R. A Nonparametric “Trim and Fill” Method of Accounting for Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2000, 95, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, S.; Tweedie, R. Trim and Fill: A Simple Funnel-Plot-Based Method of Testing and Adjusting for Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis. Biometrics 2000, 56, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.; Avolio, B. MLQ Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire; Mind Garden: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ahearne, M.; Mathieu, J.; Rapp, A. To Empower or Not to Empower Your Sales Force? An Empirical Examination of the Influence of Leadership Empowerment Behavior on Customer Satisfaction and Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popli, S.; Rizvi, I.A. Exploring the relationship between service orientation, employee engagement and perceived leadership style: A study of managers in the private service sector organizations in India. J. Serv. Mark. 2015, 29, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, J.K.; Schmidt, F.L.; Hayes, T.L. Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, S.; Pathardikar, A.; Kumar, A. Transformational leadership and turnover. Mediating effects of employee engagement, employer branding, and psychological contract. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 39, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothmann, S. The Reliability and Validity of Measuring Instruments of Happiness in the Southern African Context; North-West University: Vanderbijlpark, SA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, T. Towers Watson Employee Engagement Framework Methodology Validation; Validation Paper: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, F.A.; Aguinis, H.; Singh, K.; Field, J.G.; Pierce, C.A. Correlational effect size benchmarks. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, J.F. Interpreting the magnitudes of correlation coefficients. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory Stone, A.G.; Russell, R.F.; Patterson, K. Transformational versus servant leadership: A difference in leader focus. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2004, 25, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. To Be Fully There: Psychological Presence at Work. Hum. Relat. 1992, 45, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Handbook of Self-Determination; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Day, D.V.; Harrison, M.M.; Halpin, S.M. An Integrative Approach to Leader Development. Connecting Adult Development, Identity, and Expertise; Taylor & Francis Group, Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine, G.J.; Hartnell, C.A.; Leroy, H. Taking Stock of Moral Approaches to Leadership: An Integrative Review of Ethical, Authentic, and Servant Leadership. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2019, 13, 148–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W. Transformational leadership and performance outcomes: Analyses of multiple mediation pathways. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.-W.; Chang, S.-C.; Kuo, J.-H.; Cheung, Y.-H. Ethical leadership, work engagement, and voice behavior. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, M.; Van Dierendonck, D. Servant leadership and engagement in a merge process under high uncertainty. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2014, 27, 877–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfat, Y.; Rehman, M.; Mahmood, K.; Saleem, R. The role of leadership in work engagement: The moderating role of a bureaucratic and supportive culture. Ness Rev. Bus. Rev. 2017, 19, 688–705. [Google Scholar]

- Scheepers, C.B.; Elstob, S.L. Beneficiary contact moderates relationship between authentic leadership and engagement. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Wen, B.; Ling, Q.; Zhou, S.; Tong, M. How and when the effect of ethical leadership occurs? A multilevel analysis in the Chinese hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 974–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O. Moderating Role of Follower Characteristics With Transformational Leadership and Follower Work Engagement. Group Organ. Manag. 2009, 34, 590–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Bouckenooghe, D.; Raja, U.; Matsyborska, G. Unpacking the Goal Congruence–Organizational Deviance Relationship: The Roles of Work Engagement and Emotional Intelligence. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 124, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enwereuzor, I.K.; Ugwu, L.I.; Eze, O.A. How Transformational Leadership Influences Work Engagement Among Nurses: Does Person–Job Fit Matter? West. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 40, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.-Y.; Ming Chuan University. The Impact of Intrinsic Motivation on the Effectiveness of Leadership Style towards on Work Engagement. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2015, 11, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sleebos, D.M.; Maduro, V. Uncovering the Underlying Relationship Between Transformational Leaders and Followers’ Task Performance. J. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 13, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O. Ethical Leadership Influence at Organizations: Evidence from the Field. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 126, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O.; Hannah, S.T.; Gok, K.; Arslan, A.; Capar, N. The Moderated Influence of Ethical Leadership, Via Meaningful Work, on Followers’ Engagement, Organizational Identification, and Envy. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Ma, J.; Dong, X. Empowering supervision and service sabotage: A moderated mediation model based on conservation of resources theory. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovjanic, S.; Schuh, S.C.; Jonas, K. Transformational leadership and performance: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of basic needs satisfaction and work engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 86, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Zhou, Q.; Hartnell, C.A. Transformational Leadership, Innovative Behavior, and Task Performance: Test of Mediation and Moderation Processes. Hum. Perform. 2012, 25, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadi, M.Y.; Fernando, M.; Caputi, P. Transformational leadership and work engagement: The mediating effect of meaning in work. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2013, 34, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.C.; Idris, M.A.; Delfabbro, P.H. The linkages between hierarchical culture and empowering leadership and their effects on employees’ work engagement: Work meaningfulness as a mediator. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2017, 24, 392–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaabi, M.S.A.S.A.; Ahmad, K.Z.; Hossan, C. Authentic leadership, work engagement and organizational citizenship behaviors in petroleum company. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2016, 65, 811–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuong, M.N.; Dung, D.T.T. The Effect of Ethical Leadership and Organizational Justice on Employee Engagement—The Mediating Role of Employee Trust. Int. J. Trade Econ. Financ. 2015, 6, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Bird, J.J. Multilevel Modeling of Principal Authenticity and Teachers’ Trust and Engagement. Acad. Educ. Leadersh. J. 2011, 15, 125. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, C.-C.; Wang, D.-S. Does supervisor-perceived authentic leadership influence employee work engagement through employee-perceived authentic leadership and employee trust? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 2329–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.A.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Cummings, G. Authentic leadership and nurses’ voice behaviour and perceptions of care quality. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Q.; Liu, F.; Wu, X. Servant Versus Authentic Leadership: Assessing Effectiveness in China’s Hospitality Industry. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2017, 58, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Ahmed, F. Authentic leadership, trust and work engagement. Int. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2011, 6, 164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Gozukara, I.; Simsek, O.F. Role of Leadership in Employees’ Work Engagement: Organizational Identification and Job Autonomy. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gözükara, İ.; Şimşek, O.F. Linking transformational leadership to work engagement and the mediator effect of job autonomy: A study in a Turkish private non-profit university. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, A.J.; Biggs, A.; Hegerty, E. Work Engagement: Investigating the Role of Transformational Leadership, Job Resources, and Recovery. J. Psychol. 2017, 151, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.; Zeng, Y.; Higgs, M. The role of person-job fit in the relationship between transformational leadership and job engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2017, 32, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Lorente, L.; Chambel, M.J.; Martinez, I.M.M. Linking transformational leadership to nurses’ extra-role performance: The mediating role of self-efficacy and work engagement. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 2256–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochazka, J.; Gilova, H.; Vaculik, M. The Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Engagement: Self-Efficacy as a Mediator. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2017, 11, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulophas, D.; Hallinger, P.; Ruengtrakul, A.; Wongwanich, S. International Journal of Educational Management Exploring the effects of authentic leadership on academic optimism and teacher engagement in Thailand. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2018, 32, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Li, X. Resilience, Leadership and Work Engagement: The Mediating Role of Positive Affect. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 132, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Men, R.L. Creating an Engaged Workforce: The Impact of Authentic Leadership, Transparent Organizational Communication, and Work-Life Enrichment. Commun. Res. 2015, 44, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Sheng, Z.; Wang, Z. Linking transformational leadership and work outcomes in temporary organizations: A social identity approach. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Cho, D.; Lim, D.H. Authentic leadership and work engagement: The mediating effect of practicing core values. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.G.; Kim, J.S.; Yoon, S.W.; Joo, B.-K. The effects of empowering leadership on psychological well-being and job engagement: The mediating role of psychological capital. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O.; Akdogan, A.A. The Effect of Ethical Leadership Behavior on Ethical Climate, Turnover Intention, and Affective Commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 130, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besieux, T.; Baillien, E.; Verbeke, A.L.; Euwema, M. What goes around comes around: The mediation of corporate social responsibility in the relationship between transformational leadership and employee engagement. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2015, 39, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, M.L. Transformational Leadership and Volunteer Firefighter Engagement. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2017, 28, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alok, K.; Israel, D. Authentic Leadership & Work Engagement. Indian J. Ind. Relat. 2012, 47, 498–510. [Google Scholar]

- Penger, S.; Černe, M. Authentic leadership, employees’ job satisfaction, and work engagement: A hierarchical linear modelling approach. Econ. Res. 2014, 27, 508–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological, empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Camerer, C. Not So Different After All: A Cross-Discipline View of Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, H.H.; Huang, X.; Lam, W. Why does transformational leadership matter for employee turnover? A multi-foci social exchange perspective. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Rodell, J.B.; Long, D.M.; Zapata, C.P.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J. Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, K.T.; Ferrin, D.L. Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Meta-Analytic Findings and Implications for Research and Practice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werbel, J.D.; Henriques, P. Different views of trust and relational leadership: Supervisor and subordinate perspectives. J. Manag. Psychol. 2009, 24, 780–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Lepine, J.A. Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 909–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.N.; Tan, H.H. What happens when you trust your supervisor? Mediators of individual performance in trust relationships. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 34, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajcman, J.; Rose, E. Constant Connectivity: Rethinking Interruptions at Work. Organ. Stud. 2011, 32, 941–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; Dietz, J.; Antonakis, J. Leadership Process Models: A Review and Synthesis. J. Manag. 2016, 43, 1726–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelgesang, G.R.; Leroy, H.; Avolio, B.J. The mediating effects of leader integrity with transparency in communication and work engagement/performance. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Knippenberg, D.; De Cremer, D.; van Knippenberg, B. Leadership and fairness: The state of the art. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2007, 16, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batistič, S.; Černe, M.; Vogel, B. Just how multi-level is leadership research? A document co-citation analysis 1980–2013 on leadership constructs and outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulebohn, J.H.; Bommer, W.H.; Liden, R.C.; Brouer, R.L.; Ferris, G.R. A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1715–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakis, J. On doing better science: From thrill of discovery to policy implications. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C. Leadership in virtual teams: A multilevel perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.L.; Passos, A.M.; Bakker, A.B. Team Work Engagement: Considering team dynamics for engagement. J. Chem. Inf. Modeling 2013, 53, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decuypere, A. Unraveling the Black Box of How Leaders Affect Employee Well-Being: The Role of Leadership, Leader Well-Being and Leader Attentive Communication. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium, June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield, E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Rapson, R.L. Emotional Contagion; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kašpárková, L.; Vaculik, M.; Prochazka, J.; Schaufeli, W.B. Why resilient workers perform better: The roles of job satisfaction and work engagement. J. Work. Behav. Health 2018, 33, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, A.; Kamal, A. Impact of Psychological Capital and Authentic Leadership on Work Engagement and Job Related Affective Well-being. Pak. J. Psychol. Res. 2016, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Azanza, G.; Moriano, J.A.; Molero, F.; Lévy Mangin, J.P. The effects of authentic leadership on turnover intention. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2015, 36, 955–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.H.; Song, J.H.; Park, S.; Kim, H.K. Influential Factors for Teachers’ Creativity: Mutual Impacts of Leadership, Work Engagement, and Knowledge Creation Practices. Perform. Improv. Q. 2013, 26, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.I.; Cigularov, K.P.; Chen, P.Y.; Henry, K.L.; Tomazic, R.G.; Li, Y. The Effects of Student Violence Against School Employees on Employee Burnout and Work Engagement: The Roles of Perceived School Unsafety and Transformational Leadership. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2016, 23, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, J.J.; Wang, C.; Watson, J.; Murray, L. Teacher and Principal Perceptions of Authentic Leadership: Implications for Trust, Engagement, and Intention to Return. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2012, 22, 425–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, I.; Martínez, E.; Matute, J. From internal brand management to organizational citizenship behaviours: Evidence from frontline employees in the hotel industry. Tour. Manag. 2016, 57, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, D.N.D.; Belschak, F.D. Work Engagement and Machiavellianism in the Ethical Leadership Process. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza-Parra, S.; Molero, F.; Fuster-RuizdeApodaca, M.J. Transformational leadership and job satisfaction of police officers (carabineros) in Chile: The mediating effects of group identification and work engagement/Liderazgo transformacional y satisfacción laboral en carabineros de Chile: Los efectos mediadores de la identificación con el grupo y el work engagement. Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 30, 439–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallonardo, L.M.; Wong, C.A.; Iwasiw, C.L. Authentic leadership of preceptors: Predictor of new graduate nurses’ work engagement and job satisfaction. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A.; Nair, P.; Beehr, T.; Grossenbacher, M. The relationship of leaders’ humor and employees’ work engagement mediated by positive emotions: Moderating effect of leaders’ transformational leadership style. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2016, 37, 1083–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, D.; Charkhabi, M.; Naami, A. The relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement in governmental hospitals nurses: A survey study. Springerplus 2014, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B.-K.; Lim, D.H.; Kim, S. Enhancing work engagement: The roles of psychological capital, authentic leadership, and work empowerment. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2016, 37, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuong, M.N.; Yen, N.H. The effects of leadership styles and sociability trait emotional intelligence on employee engagement. A study in Binh Duong City, Vietnam. Int. J. Curr. Res. Acad. Rev. 2014, 2, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, H.S.; Cunningham, C.J.L. Linking Nurse Leadership and Work Characteristics to Nurse Burnout and Engagement. Nurs. Res. 2016, 65, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J. The Influence of Nurse Manager Leadership Style on Staff Nurse Work Engagement. JONA: J. Nurs. Adm. 2016, 46, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauno, S.; Ruokolainen, M.; Kinnunen, U.; De Bloom, J. Emotional labour and work engagement among nurses: Examining perceived compassion, leadership and work ethic as stress buffers. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitonga-Monga, J.; Flotman, A.-P.; Cilliers, F. Workplace ethics culture and work engagement: The mediating effect of ethical leadership in a developing world context. J. Psychol. Afr. 2016, 26, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozammel, S.; Haan, P. Transformational leadership and employee engagement in the banking sector in Bangladesh. J. Dev. Areas 2016, 50, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochalski, S. The moderating role of emotional intelligence on the relationship between transformational leadership and work engagement. Int. Leadersh. J. 2016, 8, 68–87. [Google Scholar]

- Popli, S.; Rizvi, I.A. Drivers of Employee Engagement: The Role of Leadership Style. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2016, 17, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourbarkhordari, A.; Zhou, E.H.I.; Pourkarimi, J. How Individual-focused Transformational Leadership Enhances Its Influence on Job Performance through Employee Work Engagement. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Hartog, D.N.D.; Belschak, F.D. Transformational leadership and proactive work behaviour: A moderated mediation model including work engagement and job strain. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 588–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seco, V.; Lopes, M.P. Calling for Authentic Leadership: The Moderator Role of Calling on the Relationship between Authentic Leadership and Work Engagement. Open J. Leadersh. 2013, 02, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Bae, S.H.; Park, S.; Kim, H.K. Influential factors for knowledge creation practices of CTE teachers: Mutual impact of perceived school support, transformational leadership, and work engagement. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2013, 14, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Kolb, J.A.; Lee, U.H.; Kim, H.K. Role of transformational leadership in effective organizational knowledge creation practices: Mediating effects of employees’ work engagement. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2012, 23, 65–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; Van Dierendonck, D. Servant Leadership and the Effect of the Interaction between Humility, Action, and Hierarchical Power on Follower Engagement. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.; Xanthopoulou, D. Do transformational leaders enhance their followers’ daily work engagement? Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schalkwyk, S.; Du Toit, D.H.; Bothma, A.S.; Rothmann, S. Job insecurity, leadership empowerment behaviour, employee engagement and intention to leave in a petrochemical laboratory. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent-Höper, S.; Muser, C.; Janneck, M. Transformational leadership, work engagement, and occupational success. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 663–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wefald, A.J.; Reichard, R.J.; Serrano, S.A. Fitting engagement into a nomological network: The relationship of engagement to leadership and personality. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2011, 18, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S. The Interactive Effect of Authentic Leadership and Leader Competency on Followers’ Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 153, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wihuda, F.; Kurniawan, A.A.; Kusumah, A.I.; Adawiyah, W.R. Linking empowering leadership to employee service innovative behavior: A study from the hotel industry. Tourism 2017, 65, 294–314. [Google Scholar]

- Whitford, T.; Moss, S.A. Transformational Leadership in Distributed Work Groups: The Moderating Role of Follower Regulatory Focus and Goal Orientation. Commun. Res. 2009, 36, 810–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Transformational Leadership | Authentic Leadership | Servant Leadership | Ethical Leadership | Empowering Leadership |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idealized influence | Self-awareness | Empowerment | Moral person | Delegation of authority |

| Intellectual stimulation | Balanced processing | Accountability | Moral manager | Accountability for outcomes |

| Inspirational motivation | Relational transparency | Standing back | Self-directed decision making | |

| Individualized consideration | Internalized moral perspective | Humility | Information sharing | |

| Authenticity | Skills development | |||

| Courage | Coaching for innovative performance | |||

| Forgiveness | ||||

| Stewardship |

| Leadership | N | k | r | rc | ρ | SE | Q | 95% CI | 80% CR | R2 | NFS | Trimfill (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 37,905 | 86 | 0.42 **** | 0.47 **** | 0.47 **** | 0.04 | 1311.76 **** | (0.40; 0.53) | (0.25; 0.68) | 22.09% | 254,154 | Right: 0 (5.28) |

| Transformational | 23,194 | 43 | 0.43 **** | 0.47 **** | 0.47 **** | 0.04 | 502.13 **** | (0.40; 0.55) | (0.30; 0.64) | 22.09% | 75,068 | Left: 0 (3.89) |

| Authentic | 7656 | 21 | 0.39 **** | 0.43 **** | 0.43 **** | 0.07 | 603.91 **** | (0.30; 0.55) | (0.08; 0.77) | 18.49% | 10,824 | Right: 0 (2.51) |

| Servant | 1806 | 4 | 0.34 * | 0.39 * | 0.31 *** | 0.09 | 79.46 **** | (0.13; 0.49) | (0.19; 0.59) | 9.61% | 442 | Left: 2 (1.47) |

| Ethical | 3681 | 10 | 0.52 **** | 0.56 **** | 0.56 **** | 0.03 | 40.69 **** | (0.51; 0.62) | (0.46; 0.66) | 31.36% | 6341 | Right: 0 (2.12) |

| Empowering | 1568 | 8 | 0.38 **** | 0.42 **** | 0.46 **** | 0.04 | 31.97 *** | (0.39; 0.54) | (0.31; 0.54) | 21.16% | 846 | Right: 3 (1.87) |

| Study | Leadership Attributes Based on Theory | Transformational Leadership | Servant Leadership | Authentic Leadership | Ethical Leadership |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [109] | Influence | X | X | ||

| Vision | X | X | |||

| Trust | X | X | |||

| Respect or credibility | X | X | |||

| Risk-sharing or delegation | X | X | |||

| Integrity | X | X | |||

| Role modelling | X | X | |||

| [42] | Internalized moral perspective (authentic leadership) | X | X | X | |

| Moral person (ethical leadership) | X | X | X | ||

| Moral manager (ethical leadership) | x | x | X | ||

| Idealized influence (transformational leadership) | X | x | X | ||

| [111] | Positive moral perspective | X | X | X | |

| Leader self-awareness of values, cognitions, and emotions | X | X | X | ||

| Leader authentic behaviour | x | X | X | ||

| Positive role modelling | X | X | X | ||

| Personal and social identification | X | x | X | ||

| Supporting self-determination | X | X | X | ||

| Positive social exchanges | X | x | X | ||

| Follower self-awareness of values | X | X | X | ||

| Follower internalized self-regulation | X | x | X | ||

| [49] | Concern for others (altruism) | X | X | X | |

| Ethical decision making | X | X | X | ||

| Integrity | X | X | X | ||

| Role modelling | X | X | X |

| Categories | Moderators | Study | Leadership Style |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follower characteristics | (high) Positive follower characteristics (independent thinking, willing to take risks, active learner, innovative) | [121] | Transformational leadership |

| (high) Leader–follower social capital (i.e., goal congruence and social interaction) | [122] | Servant leadership | |

| (high) Promotion focus | [6,116] | Transformational leadership Ethical leadership | |

| (high) Person–job fit | [123] | Transformational leadership | |

| (high) Intrinsic motivation | [124] | Authentic leadership | |

| (high) Need for leadership (moderating effect on need fulfilment, leads to engagement) | [125] | Transformational | |

| (high) Cognitive emotion regulation | [126] | Ethical leadership | |

| (high) Ethical ideology (moderating effect on justice perception, which leads to engagement) | [127] | Ethical leadership | |

| (high) Self-efficacy | [117,128] | Servant leadership Empowering leadership | |

| Organizational | (high) Uncertainty | ||

| characteristics | (less) Beneficiary contact | [119] | Authentic leadership |

| (more) Supportive culture | [118] | Transformational | |

| Team characteristics | (low) Group job satisfaction | [120] | Ethical leadership |

| Categories | Mediator | Study | Leadership Style |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological needs | Competence need satisfaction | [129] | Transformational |

| Relatedness need satisfaction | [129] | Transformational | |

| Psychological need satisfaction | [47] | Servant | |

| Need satisfaction | [125] | Transformational | |

| Meaningfulness | [130] | Transformational | |

| Perceptions of meaning in work | [131] | Transformational | |

| Work meaningfulness | [132] | Empowering | |

| Meaningfulness | [126] | Ethical | |

| Psychological empowerment | [1,51,53,117,133] | Servant Empowering (3x) Authentic | |

| Trust | (employee) Trust (in leader) | [70] | Ethical |

| [134] | Ethical | ||

| [19] | Ethical | ||

| [135] | Authentic | ||

| [71] | Authentic | ||

| [136] | Authentic | ||

| [137] | Authentic | ||

| Trust in organization | [72] | Authentic | |

| Trust climate (organizational) | [138] | Servant | |

| Interpersonal trust in leader (i.e., leader’s competence, leader’s benevolence, leader’s reliability) | [139] | Authentic | |

| Job resources | Job autonomy | [140] | Transformational |

| [141] | Transformational | ||

| (not significant) | [129] | Transformational | |

| Responsibility | [130] | Transformational | |

| Role clarity | [1] | Empowering | |

| Job resources in general | [125] | Transformational | |

| [142] | Transformational | ||

| Overall person–job match | [80] | Authentic | |

| Person–job Fit | [143] | Transformational | |

| Personal resources | Self-efficacy | [144] | Transformational |

| Self-efficacy | [145] | Transformational | |

| Optimism | [72] | Authentic | |

| Academic optimism | [146] | Authentic | |

| Positive affect | [147] | Transformational | |

| Work–life enrichment | [148] | Authentic | |

| Project identification | [149] | Transformational | |

| Practicing core values | [150] | Authentic | |

| Psychological capital | [151] | Empowering | |

| Organizational and team resources | Organizational identification | [117] | Servant |

| [141] | Transformational | ||

| Organizational justice | [152] | Ethical | |

| Corporate social responsibility | [153] | Transformational | |

| Perceived societal impact | [154] | Transformational | |

| Promotive organization-based psychological ownership | [155] | Authentic | |

| Group identification | [154] | Transformational | |

| Leader Attributes | Leadership effectiveness | [47] | Transformational |

| Perceived support | [156] | Authentic |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Decuypere, A.; Schaufeli, W. Exploring the Leadership–Engagement Nexus: A Moderated Meta-Analysis and Review of Explaining Mechanisms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168592

Decuypere A, Schaufeli W. Exploring the Leadership–Engagement Nexus: A Moderated Meta-Analysis and Review of Explaining Mechanisms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168592

Chicago/Turabian StyleDecuypere, Anouk, and Wilmar Schaufeli. 2021. "Exploring the Leadership–Engagement Nexus: A Moderated Meta-Analysis and Review of Explaining Mechanisms" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 16: 8592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168592

APA StyleDecuypere, A., & Schaufeli, W. (2021). Exploring the Leadership–Engagement Nexus: A Moderated Meta-Analysis and Review of Explaining Mechanisms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168592