Leading the Challenge: Leader Support Modifies the Effect of Role Ambiguity on Engagement and Extra-Role Behaviors in Public Employees

Abstract

1. Introduction

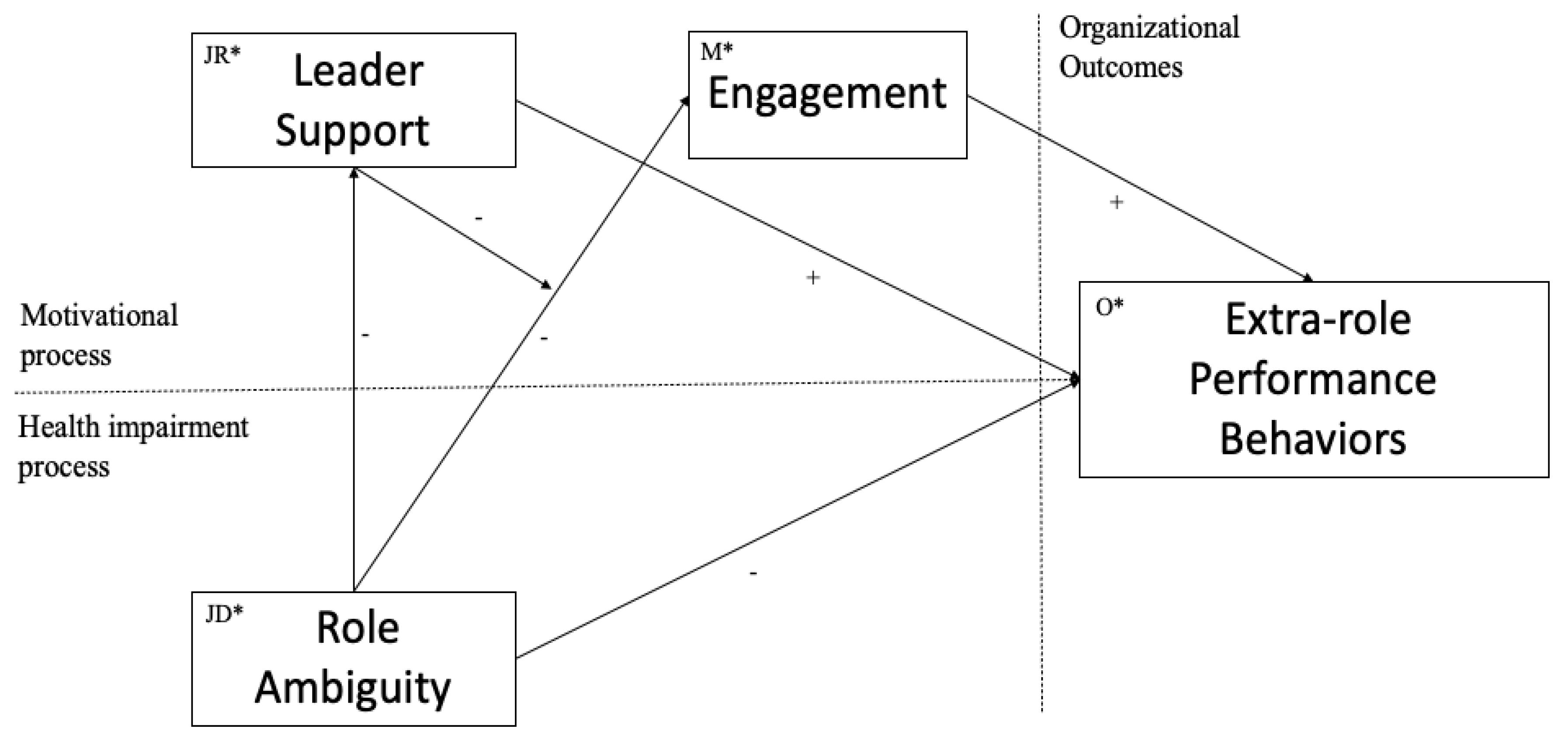

Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Sample

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Leader Support

2.3.2. Engagement

2.3.3. Role Ambiguity

2.3.4. Extra-Role Performance Behaviors

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Data, Internal Consistencies, and Zero-Order Correlations

3.2. Testing the Mediation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Investigations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Audenaert, M.; Decramer, A.; George, B.; Verschuere, B.; Van Waeyenberg, T. When employee performance management affects individual innovation in public organizations: The role of consistency and LMX. Int. J. Hum. Resource Manag. 2019, 30, 815–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Díaz, A.; Mañas-Rodríguez, M.Á.; Díaz-Fúnez, P.A.; Limbert, C. Positive Influence of Role Ambiguity on JD-R Motivational Process: The Moderating Effect of Performance Recognition. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 550219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breaugh, J. Too Stressed to Be Engaged? The Role of Basic Needs Satisfaction in Understanding Work Stress and Public Sector Engagement. Public Pers. Manag. 2021, 50, 84–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.Á.; Estreder, Y.; Martinez-Tur, V.; Díaz-Fúnez, P.A.; Pecino-Medina, V. A positive spiral of self-efficacy among public employees. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 1607–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Tur, V.; González, P.; Molina, A.; Peñarroja, V. Bad News and Quality Reputation among Users of Public Services. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2018, 34, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecino, V.; Mañas, M.A.; Díaz-Fúnez, P.A.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Padilla-Góngora, D.; López-Liria, R. Organisational Climate, Role Stress, and Public Employees’ Job Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.; Yusoff, R.M.; Khan, A. Job demands, burnout and resources in teaching a conceptual review. World Appl. Sci. J. 2014, 30, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.S.; Stazyk, E.C. Examining the Links between Senior Managers’ Engagement in Networked Environments and Goal and Role Ambiguity. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2016, 26, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinchbaugh, C.; Luth, M.T.; Li, P. A challenge or a hindrance? Understanding the effects of stressors and thriving on life satisfaction. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2015, 22, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Antognoni, H.A.; Llorens, S.; Le Blanc, P. We Trust You! A Multilevel-Multireferent Model Based on Organizational Trust to Explain Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.; Hetland, J.; Demerouti, E.; Olsen, O.K.; Espevik, R. Daily transactional and transformational leadership and daily employee engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carasco-Saul, M.; Kim, W.; Kim, T. Leadership and employee engagement: Proposing research agendas through a review of literature. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2015, 14, 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliyana, A.; Ma’arif, S. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment effect in the transformational leadership towards employee performance. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 25, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Parker, S.K. The role of leader support in facilitating proactive work behavior: A perspective from attachment theory. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1025–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.; Demerouti, E. Job demands-resources model. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Organ. 2013, 29, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands-Resources Theory. In Wellbeing: A Complete Reference Guide; Cooper, C., Chen, P., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2014; pp. 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Orgambídez-Ramos, A.; Borrego-Alés, Y.; Mendoza-Sierra, I. Role stress and work engagement as antecedents of job satisfaction in Spanish workers. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2014, 7, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. The job demands-resources model: Challenges for future research. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2011, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Fúnez, P.A.; Pecino, V.; Mañas, M.Á. Ambigüedad de rol, satisfacción laboral y ciudadanía organizacional en el sector público: Un estudio de mediación multinivel. Rev. Psicología 2016, 34, 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhou, Q.; Martinez, L.F.; Ferreira, A.I.; Rodrigues, P. Supervisor support, role ambiguity and productivity associated with presentism: A longitudinal study. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3380–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgambídez, A.; Almeida, H. Exploring the link between structural empowerment and job satisfaction through the mediating effect of role stress: A cross-sectional questionnaire study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 109, 103672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, R.; Wolfe, D.; Quinn, R.; Snoek, J.; Rosenthal, R. Organizational Stress: Studies on Role Conflict and Ambiguity; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Maden-Eyiusta, C. Role conflict, role ambiguity, and proactive behaviors: Does flexible role orientation moderate the mediating impact of engagement? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Yavas, U.; Babakus, E.; Deitz, G.D. The effects of organizational and personal resources on stress, engagement, and job outcomes. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Gevers, J.M. Job crafting and extra-role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 91, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaccio, A.; Henderson, D.J.; Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Cao, X. Toward an understanding of when and why servant leadership accounts for employee extra-role behaviors. J. Bus. Psycho. 2015, 30, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botti, A.; Monda, A. Goal Ambiguity in Public Organizations: A Systematic Literature. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 14, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillier, J.G. Linking transformational leadership to self-efficacy, extra-role behaviors, and turnover intentions in public agencies: The mediating role of goal clarity. Adm. Soc. 2016, 48, 883–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, T.M.; Prottas, D.J. Role stressors, engagement and work behaviours: A study of higher education professional staff. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2017, 39, 642–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E.; LePine, J.A.; Rich, B.L. Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical explanation and meta-analytic test. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Eldor, L.; Schohat, L.M. Engage them to public service: Conceptualization and empirical examination of employee engagement in public administration. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2013, 43, 518–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony-McMann, P.E.; Ellinger, A.D.; Astakhova, M.; Halbesleben, J.R. Exploring different operationalizations of employee engagement and their relationships with workplace stress and burnout. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2017, 28, 163–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgambídez, A.; Extremera, N. Understanding the link between work engagement and job satisfaction: Do role stressors underlie this relationship? Scand. J. Psychol. 2020, 61, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; De Cuyper, N.; De Witte, H.; Vansteenkiste, M. Not all job demands are equal: Differentiating job hindrances and job challenges in the Job Demands–Resources model. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 19, 735–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, D.; Orgambídez-Ramos, A.; Gonçalves, G. Role stress and work engagement as antecedents of job satisfaction: Results from Portugal. Eur. J. Psychol. 2014, 10, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Seppälä, P.; Peeters, M.C. High job demands, still engaged and not burned out? The role of job crafting. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 24, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Ropponen, A.; De Witte, H.; Schaufeli, W.B. Testing demands and resources as determinants of vitality among different employment contract groups. A study in 30 European countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harms, P.D.; Credé, M.; Tynan, M.; Leon, M.; Jeung, W. Leadership and stress: A meta-analytic review. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I. Weekly work engagement and flourishing: The role of hindrance and challenge job demands. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B. Daily job demands and employee work engagement: The role of daily transformational leadership behavior. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, K.M.; O’Brien, K.E.; Beehr, T.A. The role of hindrance stressors in the job demand–control–support model of occupational stress: A proposed theory revision. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadić, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W.G. Challenge versus hindrance job demands and well-being: A diary study on the moderating role of job resources. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 702–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Taris, T.W.; Peeters, M.C. Challenge and hindrance appraisals of job demands: One man’s meat, another man’s poison? Anxiety Stress Coping 2020, 33, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Hofer, A.; Kauffeld, S. Why does competitive psychological climate foster or hamper career success? The role of challenge and hindrance pathways and leader-member-exchange. J. Vocat. Behav. 2021, 127, 103542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhatre, K.H.; Riggio, R.E. Charismatic and Transformational Leadership: Past, Present and Future. In The Oxford Handbook of Leadership and Organizations; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations; Collier Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hoch, J.E.; Bommer, W.H.; Dulebohn, J.H.; Wu, D. Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A meta-analysis. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, A.E.; Griffin, M.A. Dimensions of transformational leadership: Conceptual and empirical extensions. Leadersh, Q. 2004, 15, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Zafar, A.; Zafar, M.A.; Saqib, L.; Mushtaq, R. Role of supportive leadership as a moderator between job stress and job performance. Inf. Manag. Business Rev. 2012, 4, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañas, M.A.; Díaz-Fúnez, P.; Pecino, V.; López-Liria, R.; Padilla, D.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M. Consequences of team job demands: Role ambiguity climate, affective engagement, and extra-role performance. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, W.H.; Anderson, R.E. Transformational leadership effects on salespeople’s attitudes, striving, and performance. J. Bus. Research. 2020, 110, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillier, J.G. Toward a better understanding of the relationship between transformational leadership, public service motivation, mission valence, and employee performance: A preliminary study. Public Pers. Manag. 2014, 43, 218–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Davis, R.S.; Pandey, S.; Peng, S. Transformational leadership and the use of normative public values: Can employees be inspired to serve larger public purposes? Public Admin. 2016, 94, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Vallina, A.; Alegre, J.; López-Cabrales, Á. The challenge of increasing employees’ well-being and performance: How human resource management practices and engaging leadership work together toward reaching this goal. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 60, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, I.M.; Salanova, M.; Cruz-Ortiz, V. Our boss is a good boss! Cross-level effects of transformational leadership on work engagement in service jobs. Rev. Psicol. Del Trab. Organ. 2020, 36, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, N.; Rigotti, T.; Otto, K.; Loeb, C. What about the leader? Crossover of emotional exhaustion and work engagement from followers to leaders. J. Occup Health Psychol. 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, T.W.; Davison, J.; Bliese, P.D.; Castro, C.A. How leaders can influence the impact that stressors have on soldiers. Mil. Med. 2004, 169, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, M.A.; Zhang, Y.; Crawford, E.R.; Rich, B. Turning their pain to gain: Charismatic leader influence on follower stress appraisal and job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1036–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmura Kraemer, H.; Kiernan, M.; Essex, M.; Kupfer, D.J. How and why criteria defining moderators and mediators differ between the Baron & Kenny and MacArthur approaches. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, S101–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D.A. Reflections on mediation. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, J.R.; House, R.J.; Lirtzman, S.I. Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1970, 15, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, J.M.; Meliá, J.L.; Torres, M.A.; Zurriaga, R. La medida de la experiencia de la ambigüedad en el desempeño de roles: El cuestionario general de ambigüedad de rol en ambientes organizacionales. Eval. Psicol. 1986, 3, 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, S.A.; Svyantek, D.J. Person-organization fit and contextual performance: Do shared values matter. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 55, 254–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, I.A.; Montgomery, G.H.; Szamoskozi, S.; David, D. Key constructs in “classical” and “new wave” cognitive behavioral psycho-therapies: Relationships among each other and with emotional distress. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 69, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Kelley, K. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol. Methods 2011, 16, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F.; Matthes, J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 924–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañas-Rodríguez, M.Á.; Díaz-Fúnez, P.A.; Llopis-Marín, J.; Nieto-Escámez, F.; Salvador-Ferrer, C. Relationship between transformational leadership, affective commitment and turnover intention of workers in a multinational company. Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 35, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.F. Strategic skills of leaders. Rev. Cubana Enferm. 2013, 29, 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.; De Menezes, L.M. High involvement management, high-performance work systems and well-being. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 1586–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, L.; Akdere, M. Effective leadership development in information technology: Building transformational and emergent leaders. Ind. Commerc. Train. 2018, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Derks, D. Who takes the lead? A multi-source diary study on leadership, work engagement, and job performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonagle, A. Common Method Variance. In The SAGE Encylopedia of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Rogelberg, S., Ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Simmering, M.; Fuller, C.; Richardson, H.; Ocal, Y.; Atinc, G. Marker variable choice, reporting, and interpretation in the detection of common method variance: A review and demonstration. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 473–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, A.; De Paola, F.; Ceschi, A.; Sartori, R.; Meneghini, A.M.; Di Fabio, A. Work engagement and psychological capital in the Italian public administration: A new resource-based intervention programme. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2017, 43, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Total Sample |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| N | 315 |

| % Male | 51.6 |

| % Female | 48.4 |

| Age | |

| N | 315 |

| % under 36 years old | 1.8 |

| % between 36 and 45 years old | 14.1 |

| % between 46 and 55 years old | 64 |

| % over 55 years | 20.1 |

| Academic level | |

| N | 315 |

| % Elementary or High School | 10.3 |

| % Bachelor’s degree | 23 |

| % Graduate | 55.5 |

| % Master’s degree | 10.1 |

| % PhD | 1.1 |

| Employment status | |

| N | 315 |

| % Public officials | 92.9 |

| % Ordinary employees | 7.1 |

| Job positions | |

| N | 315 |

| Managers | 7.1 |

| Pre-managers | 15.9 |

| Operating | 77 |

| Working hours | |

| N | 315 |

| Morning shift | 81.9 |

| Afternoon shift | 18.1 |

| M | SD | α | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Role Ambiguity | 1.95 | 0.81 | 0.90 | −0.608 ** | −0.416 ** | −0.483 ** |

| 2. Engagement | 4.31 | 1.34 | 0.86 | 0.465 ** | 0.487 ** | |

| 3. Leader Support | 3.94 | 1.62 | 0.88 | 0.515 ** | ||

| 4. Extra-Role Behavior | 4.70 | 1.16 | 0.82 |

| Coefficient | SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (extra-role performance behaviors) Total Effect | |||

| X (Role ambiguity) | −0.660 | 0.067 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 6.000 | 0.144 | <0.001 |

| R2 = 0.373 | |||

| F = 95.444, p ≤ 0.001 | |||

| Model 2 (engagement) | |||

| X (Role ambiguity) | −0.988 | 0.072 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 6.248 | 115 | <0.001 |

| R2 = 0.370 | |||

| F = 184.157, p ≤ 0.001 | |||

| Model 3 (extra-role performance behaviors) | |||

| X (Role ambiguity) | −0.405 | 0.082 | <0.001 |

| M1 (Engagement) | 0.257 | 0.050 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 4.393 | 0.345 | <0.001 |

| R2 = 297 | |||

| F = 64.552, p ≤ 0.001 | |||

| Model 4 (leader support) | |||

| X (Role ambiguity) | −0.806 | 0.099 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 5.526 | 0.212 | <0.001 |

| R2 = 0.173 | |||

| F = 65.543, p ≤ 0.001 | |||

| Model 5 (extra-role performance behaviors) | |||

| X (Role ambiguity) | −0.445 | 0.068 | <0.001 |

| M2 (Leader support) | 0.266 | 0.035 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 4.531 | 0.236 | <0.001 |

| R2 = 0.351 | |||

| F = 84.660, p ≤ 0.001 | |||

| Model 6 (extra-role performance behaviors) | |||

| X (Role ambiguity) | −0.311 | 0.078 | <0.001 |

| M1 (Engagement) | 0.165 | 0.049 | <0.001 |

| M2 (Leader support) | 0.231 | 0.036 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 3.694 | 0.343 | <0.001 |

| R2 = 0.151 | |||

| F = 61.195, p ≤ 0.001 |

| BootstrappingBC 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | Lower | Upper | |

| Overall indirect effect | −0.349 | 0.060 | −0.473 | −0.234 |

| IE1:X ≥ M1 ≥ Y | −0.134 | 0.048 | −0.229 | −0.039 |

| IE2:X ≥ M2 ≥ Y | −0.186 | 0.043 | −0.280 | −0.108 |

| IE3: X ≥ M1 ≥ M2 ≥ Y | −0.028 | 0.012 | −0.050 | −0.007 |

| Antecedent | Coefficient | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| X (Role ambiguity) | −0.988 | 0.072 | <0.001 |

| W (Leader support) | 0.054 | 0.084 | 0.517 |

| XxW | 0.079 | 0.037 | 0.033 |

| Constant | 6.248 | 0.115 | <0.001 |

| R2 = 0.432 F = 79.138, p = 0.000 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Díaz, A.; Mañas-Rodríguez, M.A.; Díaz-Fúnez, P.A.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M. Leading the Challenge: Leader Support Modifies the Effect of Role Ambiguity on Engagement and Extra-Role Behaviors in Public Employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168408

Martínez-Díaz A, Mañas-Rodríguez MA, Díaz-Fúnez PA, Aguilar-Parra JM. Leading the Challenge: Leader Support Modifies the Effect of Role Ambiguity on Engagement and Extra-Role Behaviors in Public Employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(16):8408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168408

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Díaz, Ana, Miguel A. Mañas-Rodríguez, Pedro A. Díaz-Fúnez, and José M. Aguilar-Parra. 2021. "Leading the Challenge: Leader Support Modifies the Effect of Role Ambiguity on Engagement and Extra-Role Behaviors in Public Employees" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 16: 8408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168408

APA StyleMartínez-Díaz, A., Mañas-Rodríguez, M. A., Díaz-Fúnez, P. A., & Aguilar-Parra, J. M. (2021). Leading the Challenge: Leader Support Modifies the Effect of Role Ambiguity on Engagement and Extra-Role Behaviors in Public Employees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8408. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168408