Flourishing of Rural Adolescents in China: A Moderated Mediation Model of Social Capital and Intrinsic Motivation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Intrinsic Motivation as a Mediator

1.2. Social Capital as a Moderator

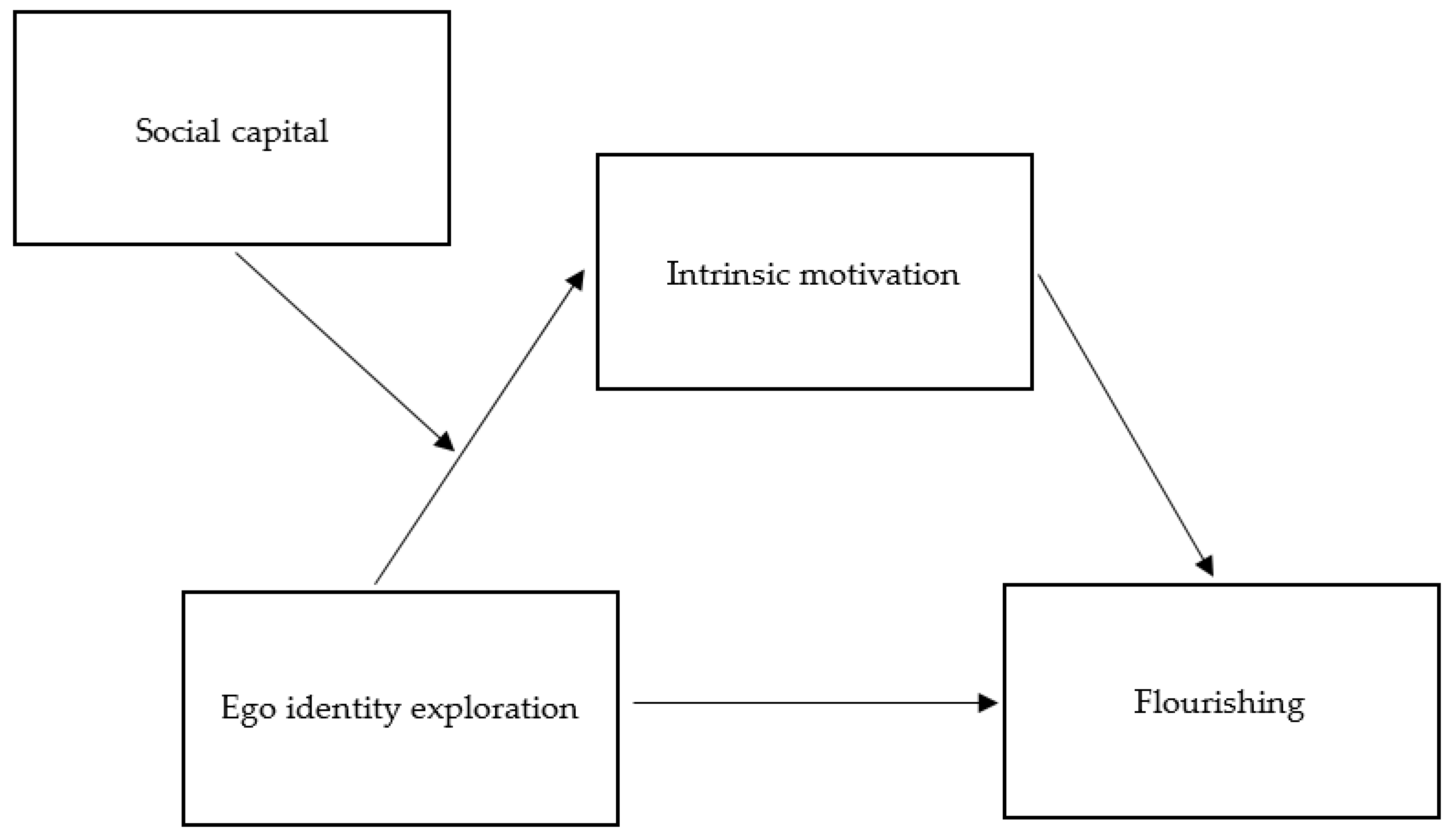

1.3. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurement

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias

3.2. Descriptive and Preliminary Analysis

3.3. Mediation Analyses

3.4. Moderated Mediation Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mash, E.J.; Hunsley, J. Evidence-based assessment of child and adolescent disorders: Issues and challenges. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2005, 34, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, X.; Wang, L. Comparative research on individual modernity of adolescents between town and countryside in China. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 6, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, S.; Helwig, C.C.; Yang, S. Predictors of children’s rights attitudes and psychological well-being among rural and urban mainland Chinese adolescents. Soc. Dev. 2017, 26, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bilige, S.; Gan, Y. Hidden school dropout among adolescents in rural China: Individual, parental, peer, and school correlates. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2020, 29, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, X.; Li, H. Bullying victimization, school belonging, academic engagement and achievement in adolescents in rural China: A serial mediation model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 113, 104946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Xu, X.; Xiang, H.; Yang, Y.; Peng, P.; Xu, S. Bullying victimization and suicidal ideation among Chinese left-behind children: Mediating effect of loneliness and moderating effect of gender. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 111, 104848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, D.; Van Yperen, N.W. The effects of strength-based versus deficit-based self-regulated learning strategies on students’ effort intentions. Motiv. Emot. 2015, 39, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Catalano, R.F.; Berglund, M.L.; Ryan, J.A.M.; Lonczak, H.S.; Hawkins, J.D. Positive Youth Development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of Positive Youth Development Programs. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2004, 591, 98–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Sun, R.T.F.; Merrick, J. Positive Youth Development: Theory, Research and Application; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781620813058. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Almerigi, J.B.; Theokas, C.; Phelps, E.; Gestsdottir, S.; Naudeau, S.; Jelicic, H.; Alberts, A.; Ma, L.; et al. Positive Youth Development, Participation in Community Youth Development Programs, and Community contributions of fifth-grade adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 2005, 25, 17–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F.A.; So, T.T.C. Flourishing across Europe: Application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 110, 837–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New well-being measures: Short scales to sssess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2002, 43, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Mental health in adolescence: Is America’s youth flourishing? Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2006, 76, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, H.; Savahl, S.; Adams, S. Adolescent flourishing: A systematic review. Cogent Psychol. 2019, 6, 1640341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kubzansky, L.D.; VanderWeele, T.J. Parental warmth and flourishing in mid-life. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 220, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity and the Life Cycle: Selected Papers; International Universities: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- La Guardia, J.G. Developing Who I am: A Self-Determination Theory approach to the establishment of healthy identities. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 44, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Ning, X.; Qin, T. The Interaction effect of traditional Chinese culture and ego identity exploration on the flourishing of rural Chinese children. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, E.; Rubini, M.; Meeus, W. Capturing the dynamics of identity formation in various ethnic groups: Development and validation of a three-dimensional model. J. Adolesc. 2008, 31, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, B.S.; Sharma, S. Role of critical thinking in ego identity statuses among adolescents. Indian J. Health Wellbeing 2015, 6, 1076–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.; Malycha, C.P.; Schafmann, E. The influence of intrinsic motivation and synergistic extrinsic motivators on creativity and innovation. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, W.; Williams, C.M. The effects of parental involvement on students’ academic self-efficacy, engagement and intrinsic motivation. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Promoting Self-determined school engagement: Motivation, learning, and well-being. In Handbook of School Motivation; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci L, E. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G.; Jungert, T.; Mageau, G.A.; Schattke, K.; Dedic, H.; Rosenfield, S.; Koestner, R. A self-determination theory approach to predicting school achievement over time: The unique role of intrinsic motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Sun, R.C.F. Parenting in Hong Kong: Traditional Chinese cultural roots and contemporary phenomena. In Parenting Across Cultures; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, A.; Flum, H. Identity formation in educational settings: A critical focus for education in the 21st century. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 37, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kroger, J. Identity, regression and development. J. Adolesc. 1996, 19, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeve, J.; Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Sociocultural influences on student motivation as viewed through the lens of self-determination theory. In Big Theories Revisited 2; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Mullis, R.L.; Waterman, A.S.; Dunham, R.M. Ego identity status, identity style, and personal expressiveness: An empirical investigation of three convergent constructs. J. Adolesc. Res. 2000, 15, 504–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markovitch, N.; Luyckx, K.; Klimstra, T.; Abramson, L.; Knafo-Noam, A. Identity exploration and commitment in early adolescence: Genetic and environmental contributions. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, J. Social Capital; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 020363408X. [Google Scholar]

- Manago, A.M.; Graham, M.B.; Greenfield, P.M.; Salimkhan, G. Self-presentation and gender on MySpace. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Qian, G.; Wang, X.; Lei, L.; Hu, Q.; Chen, J.; Jiang, S. Mobile social media use and self-identity among Chinese adolescents: The mediating effect of friendship quality and the moderating role of gender. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, S.L.; You, Y.-F.; Schwartz, S.; Teo, G.; Mochizuki, K. Identity exploration, commitment, and distress: A cross national investigation in China, Taiwan, Japan, and the United States. Child Youth Care Forum 2011, 40, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepper, M.R.; Corpus, J.H.; Iyengar, S.S. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations in the classroom: Age differences and Academic correlates. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 97, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, C.; Tomson, G.; Guo, J.; Li, X.; Keller, C.; Söderqvist, F. Psychometric evaluation of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) in Chinese adolescents—A methodological study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, P.; Chen, X.; Gong, J.; Jacques-Tiura, A.J. Reliability and validity of the personal Social Capital Scale 16 and Personal Social Capital Scale 8: Two short instruments for survey studies. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 119, 1133–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Urreta, M.I.; Hu, J. Detecting Common Method Bias: Performance of the Harman’s Single-Factor Test. ACM SIGMIS Database DATABASE Adv. Inf. Syst. 2019, 50, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, G.; Wallnau, L.B. Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781305842807. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterman, A.S. Doing Well: The relationship of identity status to three conceptions of well-being. Identity 2007, 7, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, K.; Schwartz, S.J.; Berzonsky, M.D.; Soenens, B.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Smits, I.; Goossens, L. Capturing ruminative exploration: Extending the four-dimensional model of identity formation in late adolescence. J. Res. Pers. 2008, 42, 58–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, G.R.; Marshall, S.K. A developmental social psychology of identity: Understanding the person-in-context. J. Adolesc. 1996, 19, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcia, J.E. The Ego identity status approach to ego identity. In Ego Identity; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Waterman, A.S. Developmental perspectives on identity formation: From adolescence to adulthood. In Ego Identity; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On assimilating identities to the self: A Self-Determination Theory perspective on internalization and integrity within cultures. In Handbook of Self and Identity; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney-Benson, G.A.; Pomerantz, E.M. The role of mothers’ use of control in children’s perfectionism: Implications for the development of children’s depressive symptoms. J. Pers. 2005, 73, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grolnick, W.S.; Pomerantz, E.M. Issues and challenges in studying parental control: Toward a new conceptualization. Child Dev. Perspect. 2009, 3, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joussemet, M.; Landry, R.; Koestner, R. A self-determination theory perspective on parenting. Can. Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tseng, W.-S.; Wu, D.Y.H. Chinese Culture and Mental Health; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried, A.E.; Fleming, J.S.; Gottfried, A.W. Continuity of academic intrinsic motivation from childhood through late adolescence: A longitudinal study. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, C.; Feldlaufer, H. Students’ and teachers’ decision-making fit before and after the transition to junior high school. J. Early Adolesc. 1987, 7, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, A.L.; Campione, J.C. Designing a community of young learners: Theoretical and practical lessons. In How Students Learn: Reforming Schools through Learner-Centered Education; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blazina, C.; Watkins, C.E. Separation/individuation, parental attachment, and male gender role conflict: Attitudes toward the feminine and the fragile masculine self. Psychol. Men Masc. 2000, 1, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froiland, J.M. Parental autonomy support and student learning goals: A preliminary examination of an intrinsic motivation intervention. Child Youth Care Forum 2011, 40, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex | - | - | - | |||||

| 2. Age | 12.56 | 1.38 | −0.06 * | - | ||||

| 3. Family income | - | - | 0.02 | 0.06 | - | |||

| 4. Ego identity exploration | 2.87 | 0.63 | −0.12 *** | 0.08 ** | −0.02 | - | ||

| 5. Intrinsic motivation | 3.50 | 0.82 | 0.04 | −0.14 *** | −0.02 | 0.20 *** | - | |

| 6. Flourishing | 4.18 | 1.01 | 0.09 ** | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.20 *** | 0.43 *** | - |

| 7. Social capital | 2.70 | 0.57 | −0.07 * | −0.01 | −0.10 ** | 0.29 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.32 *** |

| b | 95% CI | t | SE | p | β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paths | ||||||

| Ego → Intrinsic | 0.29 | [0.21, 0.37] | 7.15 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.22 |

| Intrinsic → Flourishing | 0.49 | [0.41, 0.56] | 13.40 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.39 |

| Ego → Flourishing | 0.21 | [0.11, 0.30] | 4.34 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.13 |

| Covariates | ||||||

| Sex → Intrinsic | 0.10 | [−0.003, 0.20] | 1.90 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Age → Intrinsic | −0.09 | [−0.13, −0.06] | −5.00 | 0.02 | <0.001 | −0.15 |

| Income → Intrinsic | −0.01 | [−0.11, 0.09] | −0.19 | 0.05 | 0.90 | −0.01 |

| Sex → Flourishing | 0.17 | [0.06, 0.29] | 2.96 | 0.06 | 0.003 | 0.09 |

| Age → Flourishing | −0.003 | [−0.04, 0.04] | −0.14 | 0.02 | 0.89 | −0.004 |

| Income → Flourishing | −0.06 | [−0.18, 0.05] | −1.07 | 0.06 | 0.29 | −0.03 |

| Total effects | ||||||

| 0.35 | [0.25, 0.44] | 6.91 | 0.05 | <0.001 | ||

| Indirect effects | ||||||

| 0.14 | [0.09, 0.19] | - | 0.03 | - |

| b | 95% CI | t | SE | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paths of indirect effect | |||||

| Ego → Intrinsic | 0.22 | [0.14, 0.30] | 5.28 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Intrinsic → Flourishing | 0.49 | [0.41, 0.56] | 13.40 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Ego → Flourishing | 0.21 | [0.11, 0.30] | 4.35 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Paths of moderation | |||||

| Social → Intrinsic | 0.32 | [0.23, 0.41] | 7.06 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| Ego × Social → Intrinsic | −0.15 | [−0.26, −0.03] | −2.46 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Sex → Intrinsic | 0.11 | [0.01, 0.20] | 2.13 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Age → Intrinsic | −0.09 | [−0.12, −0.05] | −4.95 | 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Income → Intrinsic | 0.02 | [−0.07, 0,12] | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.62 |

| Sex → Flourishing | 0.17 | [0.06, 0.29] | 2.96 | 0.06 | 0.003 |

| Age → Flourishing | −0.003 | [−0.04, 0.04] | −0.14 | 0.02 | 0.89 |

| Income → Flourishing | −0.06 | [−0.18, 0.05] | −1.07 | 0.06 | 0.29 |

| Conditional direct effect | |||||

| M − SD | 0.30 | [0.19, 0.41] | 5.46 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| M | 0.22 | [0.14, 0.30] | 5.28 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| M + SD | 0.13 | [0.03, 0.24] | 2.63 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Conditional indirect effects | |||||

| M − SD | 0.15 | [0.08, 0.21] | - | 0.03 | - |

| M | 0.11 | [0.06, 0.15] | - | 0.02 | - |

| M + SD | 0.07 | [0.01, 0.12] | - | 0.03 | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, S.; Qu, D. Flourishing of Rural Adolescents in China: A Moderated Mediation Model of Social Capital and Intrinsic Motivation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158158

Guo S, Qu D. Flourishing of Rural Adolescents in China: A Moderated Mediation Model of Social Capital and Intrinsic Motivation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(15):8158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158158

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Sijia, and Diyang Qu. 2021. "Flourishing of Rural Adolescents in China: A Moderated Mediation Model of Social Capital and Intrinsic Motivation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 15: 8158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158158

APA StyleGuo, S., & Qu, D. (2021). Flourishing of Rural Adolescents in China: A Moderated Mediation Model of Social Capital and Intrinsic Motivation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 8158. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158158